“Though levels of distrust among teachers about their students’ academic integrity have gone down [since last year—2023], more than half of teachers still report eroded trust – 52 percent of teachers agree that generative AI has made them more distrustful of whether their students’ work is actually theirs.”

(Dwyer & Laird, March, 2024, Up in the Air, Center for Democracy and Technology)

How important is trust in human relations?

In Plato’s Republic trust is linked implicitly to justice—we are witnessing an erosion of justice in real time as societal trust in human relations weakens. St. Augustine emphasized trust in God, not thy neighbor. Human relations are inherently under a cloud. As I read Melville’s tale of the whale, wisdom and trust are unrelated so being wise like Plato or St. Augustine is no reason to trust; wisdom often morphs into woe which sometimes morphs into madness. Or we could follow Nietzche beyond good and evil, take the perspective that the task of humankind is to learn to live with untruth.

From my perspective absolutes are absolutely foolish, but the public school seems to align itself more with the idealism of Plato than the existentialism of Nietzche. When a school reaches the ideal standard, its principal is a Prince, its teachers seek harmony among themselves and their students, its students are committed to learning the right things in the right way, its surrounding community cherishes the school as an academy of right thinkers, and everybody trusts standardized tests.

Trust is hard to come by in schools these days, and its scarcity is playing havoc with learning. Governors are interfering with the design of AP tests. Simple things like using the appropriate bathroom are amped up to the level of debate previously reserved for issues of teaching and learning. Librarians are being fired indiscriminately. Teachers are walking away from their classrooms. The problem of mistrust goes well beyond AI.

*****

From the outside ten years away from a campus or school, all American public schools look pretty much the same to me—classrooms, desks, linoleum or carpet floors, an office with secretaries, more and more technology, tests, textbooks, teachers, students, cafeterias, multipurpose rooms, report cards, principals, truant officers, etc. From an insider’s memories close up, however, schools are as unique as human faces.

I’ve worked for extended time periods in at least thirty different public schools as a teacher, a reading specialist, a professional developer, and a researcher. I learned that the teaching profession is a calling, and teachers feel a personal and professional obligation to teach children well despite perennial and deep institutional problems. I realize that when they say they mistrust their students to demonstrate academic integrity, they speak from a place of altruism.

I also understand the depth and intensity of the protective response educators have when schools are threatened. During political turbulence, like turtles, schools retract their limbs, head, and tail inside their shells, trying to maintain an equilibrium until the storm passes. When provoked by the media, like hedgehogs, they curl into tight balls, their quills a prickly defense. Unwelcome mandates and capitalist brokers who demand measurements, poking and prodding for evidence of a return on investment, crying out for reform, turn teachers into snails, retreating into their classrooms and closing their doors, a defense formed from grains of academic freedom glued together with tenure.

*****

An unexpected threat showed up out of the blue just before winter break in 2022 after Thanksgiving: An artificially intelligent machine capable of actually doing students’ homework assignments. The initial response was to forbid it. Soon a fire hose of media reports blasted out news of an epidemic of AI-involved cheating in school. As results from the CDT survey indicate, the fire is raging. Results from this survey of a nationally representative sample of middle and high school teachers conducted in November and December, 2023, reveal a teaching force frustrated by this technology. One thing teachers do not want is to increase discipline problems:

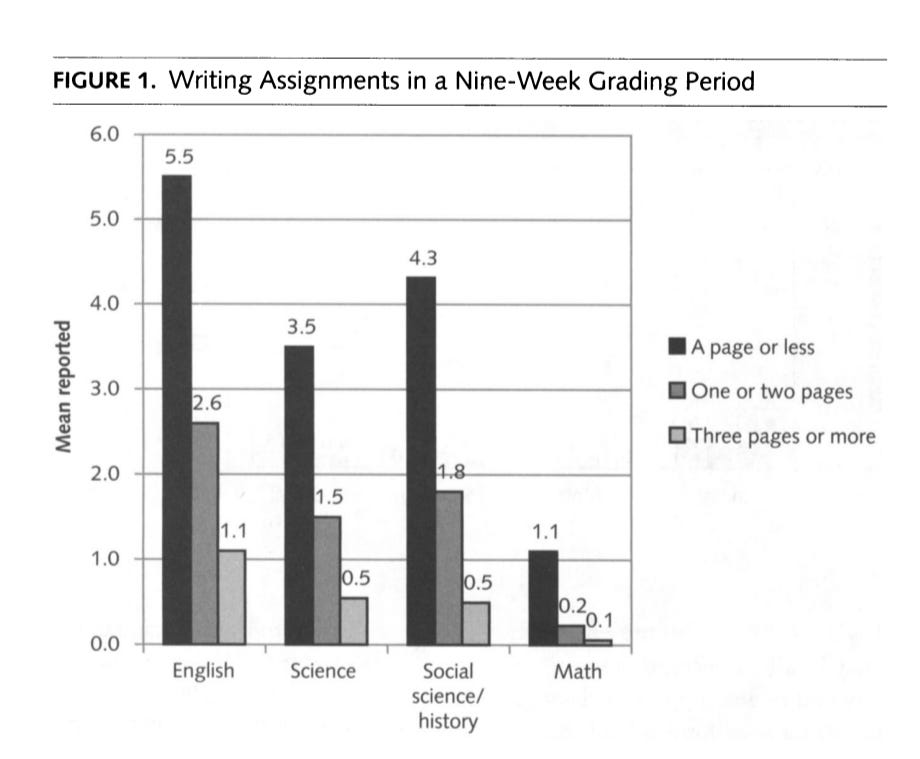

The survey design did not attempt to ferret out what types of assignments teachers see as most susceptible to corruption. The ubiquitous reading assignment is potentially a good candidate. Typical surveillance techniques to ensure students read their assignments like pop quizzes are compromised depending on how the teacher defined “reading assignment.” An assignment to read the section from page 175-183 giving bare bones information about the War of 1898, for example, which might require say 30 minutes to read, can be accomplished in a few minutes with the bot (the following text popped up in under a minute). I prompted the bot “Give me the bare bones of the War of 1898”:

In the Pre-Bot era, it’s highly unlikely that a teacher would assign something like “Go online and find out as much as you can about the War of 1898 and come back to class ready to share.” The presence of a textbook in a history class isn’t trivial. Content has been vetted through many levels of review. Tacit agreements have been made from commercial publishers to state departments of education to district administration stipulating that the content is reliable. Teachers know in advance what students will come to class with in their heads if they read the assignment—and they will know who hasn’t done the reading. Now-a-days, reading the assignment as given may constitute an aspect of academic integrity. Knowing the content isn’t the point.

Plagiarism in written work has become much more of a hot button issue, probably because using the bot to create a text and then passing it off as an original piece in class is clear cut fraud. Cutting and pasting bot-produced text and printing it out or uploading a document as one’s own work is academic crime plain and simple. But the scarcity of writing assignments in middle and secondary schools is at odds with the rise in levels of academic mistrust and corresponding punishment. If research is any guide, there simply isn’t all that much original writing going on.

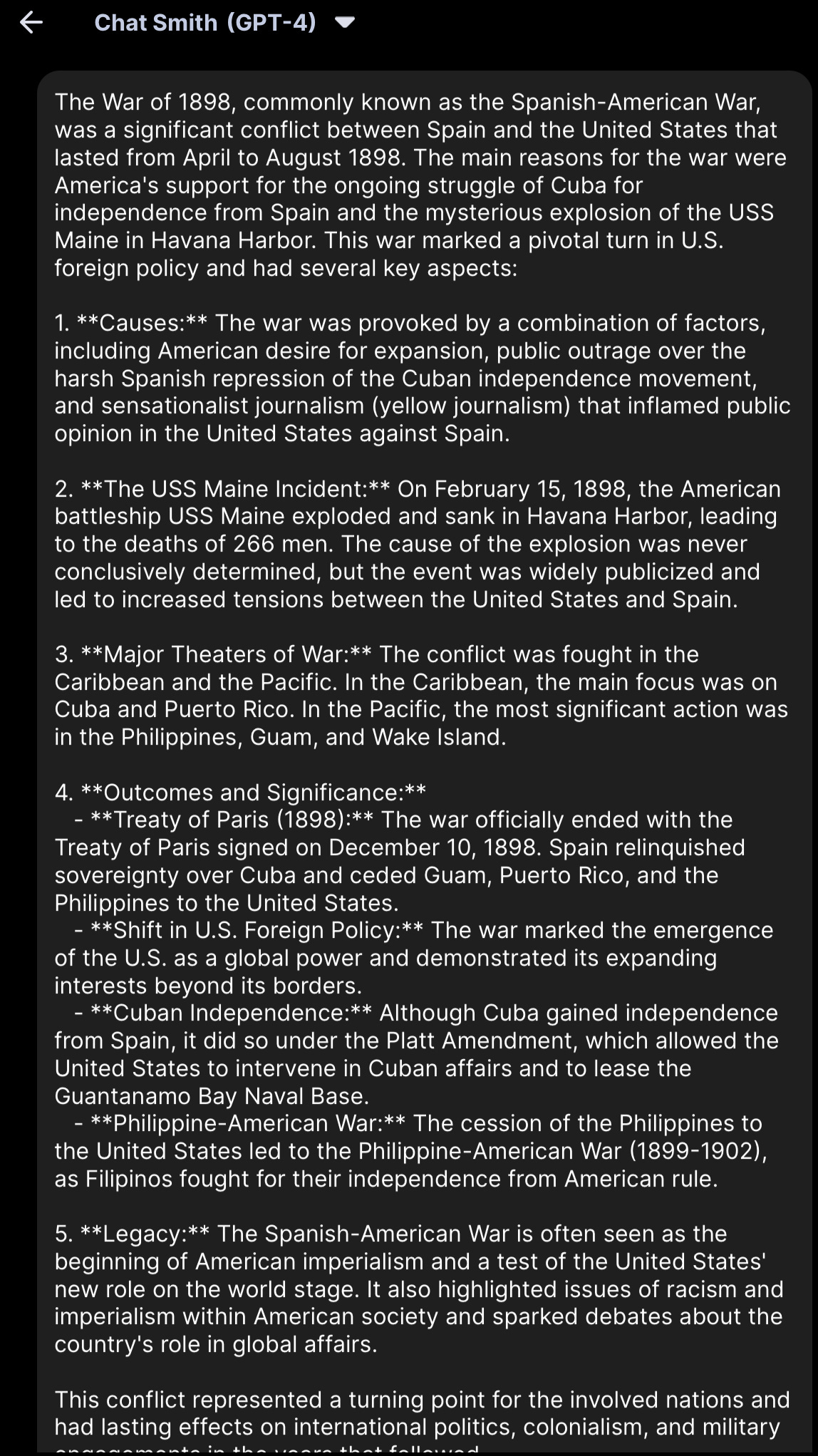

Applebee and Langer (20111) visited “…260 English, math, social studies, and science classrooms in 20 middle schools and high schools in five states (schools all chosen for reputations for excellence in the teaching of writing), interview[ed]…220 teachers, …administrators, and…138 students in these schools, and [conducted] a national survey of 1,520 randomly selected teachers.” Their objective was to find out how teachers were assigning writing across these four subjects for a nine-week grading period. Using expected length and frequency of assignments, a crude but resonant indicator, here is what they found:

As I thought about this graphic, I wondered if this finding could possibly be true. Just one assignment of three pages or more each nine weeks in English? I would have guessed at least one mini-assignment per week at least. Applebee did a similar study in 1979 and found even fewer occurrences of writing assignments. From this perspective there has been an increase since 1979, but the slow pace of increase between 1979 and 2011 seems to validate both the 1979 and the 2011 findings.

In the absence of current observational data from expert classroom researchers, it seems reasonable to assume an increase in number of writing assignments between 2011 and 2024, perhaps even deeper changes in assessment type and format given greater access to a variety digital modalities. In any event, consonant with the findings from Dwyer and Laird (2024), immediately after AI’s introduction in December, 2022, I read media report after report bemoaning student cheating and plagiarism. One teacher was quoted in a Science Digest article (April 24, 2023) talking about this issue as follows: “It can outperform a lot of middle school kids,” Vogelsinger says. He might never have known this one student he was focused on had used the bot except for one thing: “He copied and pasted the [assignment] prompt.”

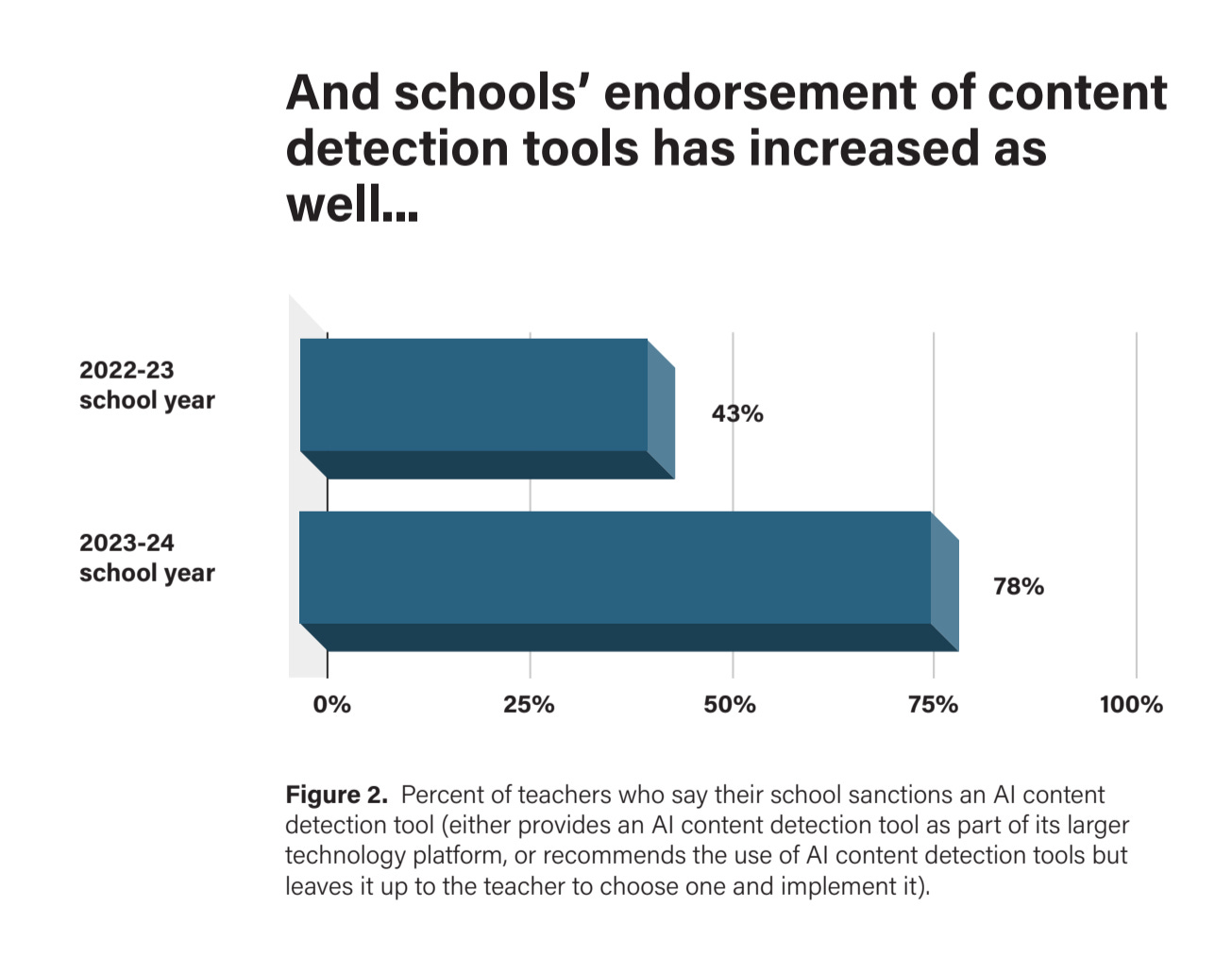

So the search is on for surveillance strategies. Despite a widespread lack of confidence in AI detection devices, the following figure depicts a rise in regular teacher use of AI as the solution to its own problems. But this solution cuts both ways. Ancdotes of students falsely accused of plagiarism haunt teachers who have experienced moral angst, boxed into a corner with steep consequences for learners for false positives. Teachers understand the devastation a child falsely accused of cheating on an especially challenging assignment can leave behind.

I argue that this mistrust of students in middle and secondary education revealed in the CDT survey, mirrored at universities as well, this cycle of suspicion, mistrust, and surveillance, is a byproduct of American school culture made more salient by the bot. Martin Covington, who was a senior researcher at the Institute for Personal and Social Psychology at UC Berkeley, articulated the deleterious impact on student learning the quest for grades has had in his book Making the Grade: A Self-Worth Perspective on Motivation and School Reform (1992). Self-worth is an internal assessment heavily influenced by participation in history and culture. Those who bemoan loss of academic integrity brought on by the bot would do well to think about the following excerpt from a UCB website summarizing a Covington presentation:

“Professor Covington began by discussing the reasons that students give for learning material in their undergraduate courses. When asked what makes them study and work hard in college, undergraduates typically say that they are trying to get the best grade possible. Grades, in fact, are the primary focus of most students. Only as secondary reasons do students list the desires to become competent, to prove themselves, and to avoid mistakes. Learning about the content of the course for its own sake is the last of the reasons students give.”

Schneider and Hutt (2014) published a damning history of the social and cultural construction of the American letter grading system. In the early 19th century teachers had no obligation to evaluate student learning beyond personal interactions with learners. Comparing one learner with another to rank them was unthinkable and unnecessary. By the late 19th century Yale reportedly created the model in use today, and as the factory model, scientific management, standardized tests, intelligence tests, and the like took hold, the following occurred (Schneider and Hutt, 20142):

“From the elementary grades up through advanced graduate programmes, instructors spend hours each week correcting papers and exams, students wring their hands over grades and steal glances at each other's scores and parents express various levels of anxiety about the marks their children are earning. Grades have become such an important feature of adolescence that we have even invented short-hand references like the grade point average so that a student's academic record may be expressed with the seeming precision of a single number and judged at a glance.”

Getting the turtle to relax, the hedgehog to uncoil, the snail to break its seal—stubbornness has kept public schools alive throughout its difficult history. There is nothing to suggest that educators on their own created a culture of schooling which linked self-worth to grades. In fact, before the Era of Standardized Testing caught fire, educators favored linking self-worth to effort. Ironically, at the moment in time when artificial intelligence emerged to supplement human intelligence, it is cheating in school to use it. Many of the problems with public schools are not technical nor scientific, but human and cultural.

*****

After six years of teaching English Composition at two California community colleges as a freeway flyer—I loved it!—I began to teach a self-contained fourth grade in 1986. The time was ripe for me to make a change. The writing pendulum in California public schools was swinging from standardized tests of editing skills toward state-level direct holistic writing assessment. As the appointed year of the rollout of the on-demand writing test approached, administrative interest in teacher professional development at the elementary level among districts increased. I wanted to teach writing to children—and I wanted to teach reading.

My experience teaching composition, my recently acquired reading specialist credential, and my willingness to talk about it all ad nauseum was attractive to the principal who hired me despite my having no elementary teaching experience. Becoming a California Distinguished School was everyone’s aspiration back then; those who toiled in classrooms understood its symbolic power. The path wended its way partly through test scores, but this was coming up on the age of Joe MacDonald’s warm, cool, and hard questions, the age of deep reform. The word assessment was undergoing rehabilitation. In a few years newspapers would rank schools publicly by their writing test scores.

Early on that year, my first year in fourth grade, at a mandatory after school workshop, I participated in an inservice on a popular approach to writing instruction at the elementary level which gave me pause. The district had contracted for a series of presenters to run what quickly became clear to me as non-solutions.

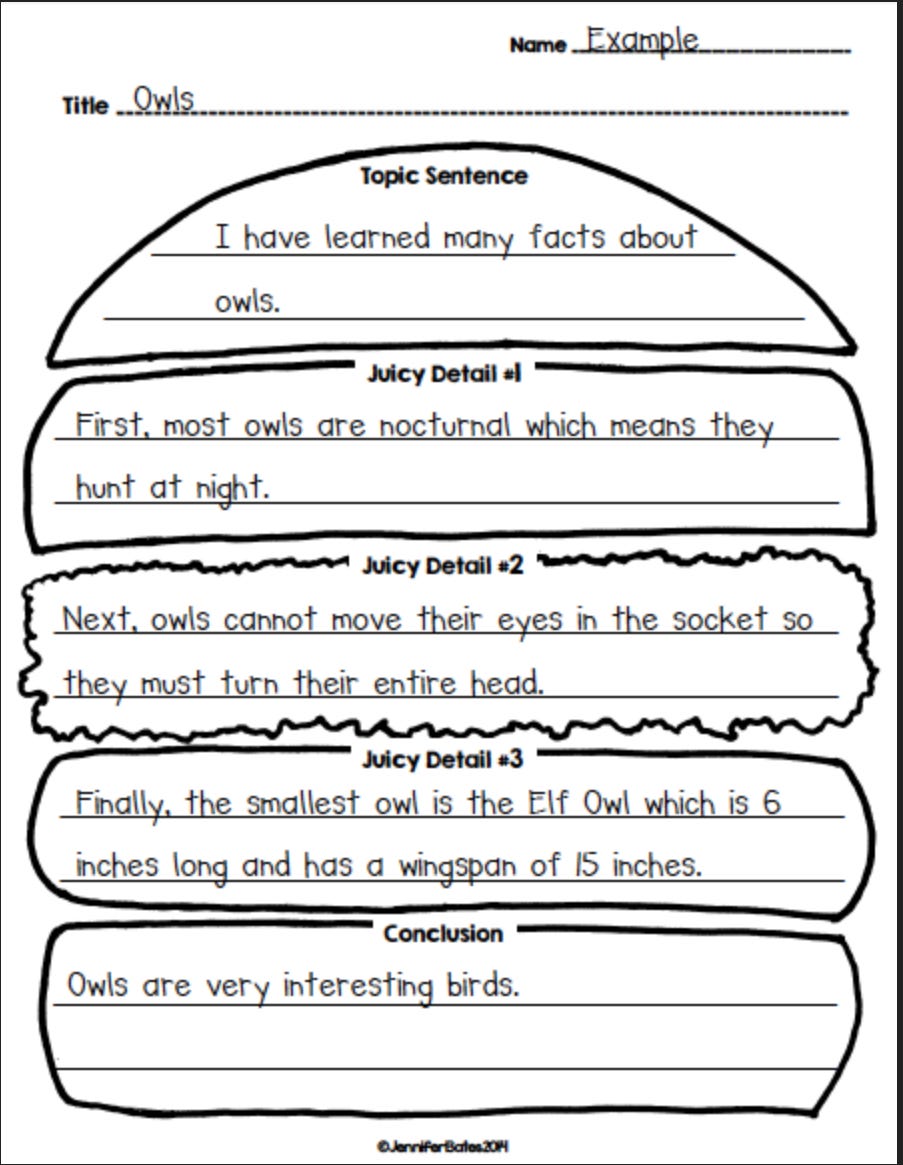

The entire teaching staff gathered in the library at tables arranged around an overhead projector. On the screen was a blank transparency roll on which the presenter drew a hamburger on a bun, pokies of green coming from under the top yellow bun half, melted orange cheese oozing from the perimeter of the bottom brownish half.

“This hamburger,” he said, pausing for suspense, all eyes on him. “This hamburger tells you everything you need to know about teaching young kids to write. Here’s your topic sentence, here’s your meat, here’s your concluding sentence.”

“Anybody here like to work in a garden? No? Anybody like cats? Yes? So… ‘Cats make cool pets.’” He wrote on the transparency. “Why? Somebody? Anybody? I need one juicy detail. ‘First, they are quiet and keep to themselves though they do curl up on the couch. Second…” He went on to model the power of the hamburger metaphor to scaffold the paragraph.

My principal had warned me. Nobody on site had a clue about teaching writing. She admittedly didn’t. She knew her teachers. Some talented math teachers, some great reading teachers. She knew the credential programs didn’t require a methods course on writing. They didn’t require a course in children’s literature either. Now suddenly it’s the next big thing, literature and writing. It would be nice if someone somewhere had a long term plan.

As it turned out, the hamburger made its mark. Since we were making hamburgers, not paella, it didn’t matter too much the quality of the meat. The teacher takes up the surveillance role and looks for conformity and progress toward becoming a better burger flipper.

Researchers have known since the 1960s that writers publishing their work outside of school rarely, if ever, write hamburger paragraphs. The arrangement and presentation of ideas and information are often tentative, fluid, and experimental as a draft emerges, changes, and, after much give and take, gets dialed in. Only in school is the goal to write a paragraph or five with little regard for its content. Only in school are writers given an assignment with little wiggle room and standardized expectations, an assignment that every student in the classroom is also writing, an assignment written from a cookie cutter prompt simply to fulfill the assignment.

***

Originally conceptualized by Gramsci in the context of Marxist philosophy, hegemony is a term of political science used to describe the relationship between a dominant ruling class and a submissive oppressed class in a capitalist society. The ruling class sustains its power not through force, but through institutions which promulgate ideas. When these ideas or ideologies become common sense, just the way things are, control over the subjugated group is complete, and the dominated are complicit.

Hegemony can be military force, cultural practices, political power, and economic control. Often a prevailing group maintains its dominant position through a combination of explicit coercion and subtle forms of consensus-building, where the hegemonic power shapes or influences the preferences and interests of subordinate groups. In the case of public schools, children are indoctrinated into the norm of quantified indicators of self-worth bestowed by external authorities along a continuum of gold stars to valedictorian.

Course credit and pressure to exert effort on academic tasks according to specs to produce a desired grade leaves students little room for more nuanced learning. What sense would it make to waste time satisfying an interest or pursuing a new question? Learners willing to risk passing off bot printouts as original work operate from a soft sense of self-worth and reveal a mental model of schooling as a game, a maze. These attitudes ought to surface during learning styles assessment practices long before a disturbing breach of academic integrity.

Teachers who not infrequently evaluate students as failures (F) sometimes see it as a badge of honor, a symbol of their own integrity. Some intend to motivate children to work harder despite a long research tradition documenting the demotivating effects of low grades. Teachers who often assign As to students sometimes also view it as a motivator, but with each “A” students are trained to work harder for extrinsic rewards instead of intrinsic satisfaction.

The perception of a fixed hierarchy of human ability evidenced by the ubiquitous phrase “an A student” or “a C student” can become a fixed belief about human learning in the minds of students. Psychologists have documented the pernicious effects of this hierarchical mindset on willingness to exert effort to learn. If ability determines learning, if ability is fixed, then there is little point in a C students working harder. Why not try AI?

Viewing the individual as the sole source of learning reinforces the hegemony of grades. On this view the individual is responsible for their success as well as their failure. Even a vague understanding of social learning theory, of learning as legitimate participation in a community of learners calls individualism into question. In a setting where each person is an island, academic performance of consequence is accomplished alone in isolation (keep your eyes on your own paper). The fact that cognition is distributed across community participants, that collaborative work can raise the level of performance of every individuals is discounted when the prize is the individual grade or score.

*****

Distrust in students’ academic integrity is a symptom, not a cause, of a much deeper problem. Micromanaging students’ uses of AI, forbidding them from using it, calling them on the carpet for breaches of academic integrity, and punishing them have some short term appeal as solutions. Looking to administrators to create and enforce policies is unlikely to impact underlying dynamics of academic oppression. Long term answers will emerge only from reimagining the relationship between teachers and students.

Time honored perspectives on secondary school teachers can change to relieve them of implementing the A-F grading scheme or a facsimile to make the job of college admissions personnel less demanding. At a minimum, negotiated evaluation with documented teacher feedback and learner structured self-assessments, including audio and video recordings, ought to form the core of high-stakes evaluations like reports to parents, which ought properly involve teacher and student commentary against local benchmarks and institutional milestones. AI itself as a data analyst can support a more qualitative approach to local knowledge-building and trust-making at the human level among all stakeholders to enhance the justice of each high-stakes decision.

Trust is a big word, pointing to essential cultural and social tissue enabling cooperation and meaningful interactions. Building trust takes time, consistency, and goodwill. Broken trust is difficult to repair, especially when a student who took an assignment seriously is indicted for plagiarism. As a profession teachers need to begin to embrace and learn artificial literacy pedagogy (ALP) to do better in this new world rather than try to limit or constrain our children’s access to it.

Applebee and Langer (2011). A Snapshot of Writing Instruction in Middle Schools and High School. The English Journal , July 2011, Vol. 100, No. 6 (July 2011), pp. 14-2

Schneider & Hutt (2014). Making the grade: A History of the A-F Grading Scheme. Journal of Curriculum Studies, Vol. 46, Issue 2, pp. 201-224.

Incredible work, Terry. A very comprehensive case.

This piece provides a solid theoretical vision for the work ahead.

Now the challenge of integrating itself principles into systems that focus so much on products, results, grades. I have toyed some with alternative grading strategies this year, allowing my students to revise to their hearts' content, but the school's demand for a final grade always seems to undermine these efforts. It seems that the best we can do most of the time is strive for minimal harm.