In 1995, Bill Gates wrote The Road Ahead, positioning himself as a visionary who foresaw the digital revolution1. The narrative was compelling: a brilliant mind who dropped out of Harvard, came from an upscale family, worked tirelessly in his garage, and through God-given intellectual force created one of the most valuable companies in history.

The story fits neatly into our cultural framework of individual genius and solitary achievement, an example of good boot straps. It's a story that both reveals and shapes how Americans think about learning, success, and human potential. Yet a closer, more critical reading excavates a different picture. Throughout the text, there's a pattern of describing extraordinary advantages in a matter-of-fact way.

In the following 1995 quote, Gates normalized his childhood experiences which, especially during the middle of the 20th century, were perhaps 4 or 5 standard deviations from the mean in the 1950s and 60s:

"The computer was our toy. We grew up with it. And when we grew up, we brought our toy with us."

His experiences playing with “our toy” began to pay off as he was entering adolescence. When the normal child felt fortunate to have a color tv, Bill was living on another planet:

"I wrote my first program for a computer when I was thirteen years old. A program tells a computer to do something. My program told the computer to play a game. This computer was very big and very slow. It didn't even have a computer screen. But I thought it was wonderful."

Gates’ early exposure to mainframe computing came through a machine at Lakeside School, which connected to a General Electric (GE) time-sharing mainframe made possible by the Lakeside Mothers Club. Gates took this opportunity to develop programming skills, explore software development, and even created practical applications like a class scheduling system.

"After I wrote that first program at the age of thirteen, my friend Paul Allen and I spent a lot of time using computers. Back then computers were very expensive. It cost forty dollars an hour to use one. We made some of our money during the summers, when we worked for computer companies."

In 2009 he reflected on his good fortune as follows:

“Well, I was lucky in many ways. I was lucky to be born with certain skills. I was lucky to have parents that created an environment where they shared what they were working on and let me buy as many books as I wanted.”2

Some fun facts about Lakeside School in Seattle in 20243: It has an average class size of 17, it offers 140+ different courses for upper-level students, it has a 37-1 ratio of counselors to seniors, over 80% of students participate every year in art education.

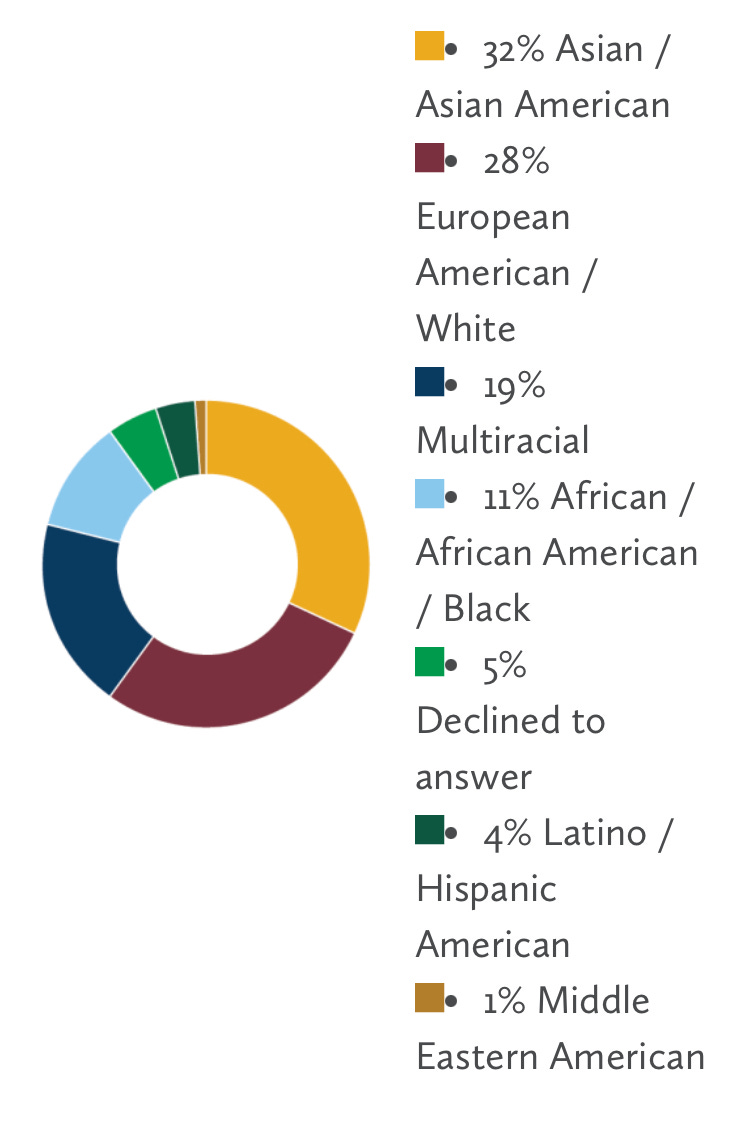

It offers 40+ arts performances, workshops, retreats, student art shows, and festivals every year, it has an annual tuition of $44,770, a third of its student population pays only $12,445 after subsidy, and its racial/ethnicity breakdown looks like this:

Bill’s mother served on the board of IBM and helped secure his first major contract. The "garage startup" was funded by family wealth that fortunately allowed risk-taking without consequence. These facts don't diminish Gates' achievements, not at all. They contextualize them within a complex web of advantages, relationships, and shared knowledge. They also underscore the vast differences in opportunity to learn attributable to economic and cultural materialism.

*****

Our public schools haven’t changed all that much since the time of Gates’ childhood. They still operate largely on the premise of individual achievement. Students sit in isolated desks, take tests alone, and receive grades that supposedly measure their personal merit.

Our corporate cultures similarly mythologize the sole innovator, the standout performer, the exceptional individual. Participants in corporate culture track individual KPIs (Key Performance Indicators), celebrate individual promotions, and award individual bonuses.

According to recent research on the teaching of teamwork, universities often focus on individual assessments, such as exams and assignments, to evaluate student performance, despite documented problems with enacting teamwork in corporate America.

While teamwork and collaborative projects are sometimes taken up in college, individual metrics remain dominant because they are familiar, easy to keep track of, and align with traditional grading systems.4

This dominant administrative framework enshrines the individual as the outcome of education. This framework is widely considered logical, measurable, and fair, as natural and normal as desks and grades—until you start informally talking about personal experiences in school, as I have a tendency to do.

Memories of the teachers of the past are sometimes filled with joy, occasionally just ok, rarely terrifying. People who have flunked a grade in elementary school are almost uniformly traumatized to varying degrees by the memory. People who graduated high school with a 2.3 GPA carry inside themselves self-doubt and varying shades of resentment.

The truth is, this individual meritocracy is not logical, it is very challenging to measure, and it is patently unfair. Teachers have responded to my provocations about the lunacy of traditional grades over the years with incredulity. When I’ve asked teachers in training to imagine teaching without grades, for many, their imagination can’t go there.

In STEM disciplines particularly, individual achievement provides for arguably conceptually clear metrics and rewards merit in a straightforward way. Solving an equation correctly is a pure indicator of knowledge, some teachers believe. The question that bears examination, however, is whether this model accurately reflects how humans actually learn, create, and achieve such knowledge. Even in STEM, individuals are not completely responsible for their achievements, for good or ill. Think Bill Gates. There is much more to the story.

*****

Gates in 1995:

"For this new system of telecommuting to work better, businesses will have to find a new way of thinking about work time. When you are in the office, the company pays you for every hour that you are there. When you are telecommuting from your home, there will be times when you are looking after the baby or doing other things."

Finding a “new way of thinking about work time” applies to whom? Company executives? In 1995 “time on task” was as potent a theme in offices as it was in school.

Buying and selling time is an insidious form of modern servitude. It reduces human capability to a commodity, measuring life itself in hourly increments while ignoring the reality that our most valuable contributions like insight, creativity, understanding refuse to punch a clock.

When we sell our hours, we aren't just selling labor; we're selling pieces of our finite existence. And when organizations like schools or businesses buy those hours, they perpetuate an illusion: that human potential can be parceled out in neat temporal blocks, that innovation operates on a schedule, that learning operates on a bell schedule.

The tragedy isn't just economic. We've built our entire educational and economic infrastructure around this fiction, and in doing so, we've normalized a profound misunderstanding of what makes us human.

In 1995, Bill Gates envisioned liberating workers from their offices, suggesting we'd need "new ways of thinking about work time." Yet embedded in his vision was an old industrial logic—that time somehow equals value, that hours measure worth.

Consider how this plays out in real human lives. A programmer stares at her screen for seven hours, stuck on a problem. In hour eight, walking to get coffee, the solution crystallizes. In the current system, we value the seven hours of frustrated staring over the moment of insight. We've institutionalized inefficiency while claiming to worship productivity.

The damage runs deeper in education. We segment learning into time blocks because it's convenient for scheduling, not because it serves human development. But our system, anchored to the clock rather than comprehension, marches steadily forward, measuring the mastery of factoids and algorithms, praying these indicators are the ones that matter.

The bitter truth? Those at the top of organizations, the executives, the entrepreneurs, the innovators, have always operated on a different clock. Their value is measured in outcomes, ideas, leadership. Is there empirical evidence that attending elite schools immunizes young learners from hardship and deprivation that makes them more likely to show up in a salaried rather than an hourly job. In fact, yes there is.

A 2024 study5 looked into this question with some unsurprising results. The url will take you to it. I will quote one long paragraph from the study to frame the forces at work in the lives of poor children;

“Decades of research have isolated the intense, widespread, and long-term effects of family SES from birth (see Evans, 2004, 2006 for reviews). As a result, we now know that infants and young children from low SES families are more likely to experience threats to healthy development due to a combination of parental (e.g., harsh or inconsistent parenting and absentee parents), peer (e.g., rejection and aggressive role models), school (e.g., lower expenditure per school and pupil and poorly trained teachers), and neighborhood characteristics (e.g., crime snd poor parental supervision). These children are also more likely to experience poor physical environments (e.g., noise, overcrowding and environmental toxins), frequent disruptions and dislocations (e.g., evictions and changes in family dwelling), and nutritional deficits (see Evans & Kim, 2010) stemming from their greater difficulty in accessing healthy foods (e.g., fewer supermarkets and higher prices).”

Gates pointed to email as the disrupter of the traditional work hour as the unit of value much like we hear fears that the efficiency AI brings to us is going to destroy our work ethic. Time-based teaching, learning, measurements for everyone else, fluid, boutique, well-resourced campuses and lifestyles for the elite construct a subtle but durable class division based on who gets to transcend the tyranny of the timesheet.

Here's what makes this particularly painful: we know better. Cognitive science shows us that creativity and learning follow their own rhythms. Innovation emerges from the spaces between focused work—during walks, in dreams, in conversation. Understanding deepens in recursive cycles, not linear hours.

Perhaps it's time to acknowledge that when we chain human potential individual by individual, task by task, to the clock and the standardized test, we're measuring neither productivity nor learning. We’re measuring compliance. And in doing so, we may be sacrificing our most precious resource: the untamed, unscheduled moments where true breakthroughs emerge.

The question isn't whether we need new ways of thinking about time. The question is whether we're ready to face what that really means.

https://eislibrary.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/billgates-the_road_ahead.pdf

https://www.bfsinvest.com/bill-gates-and-the-story-of-microsoft

https://www.lakesideschool.org/about-us/fast-facts

https://www.jotse.org/index.php/jotse/article/view/1478/639

https://theconversation.com/from-playground-to-boardrooms-how-childhood-and-adolescence-shape-future-leaders-231584

Nice job, Terry, as always!