The Great Equalizer

“Every generation of reformers has believed in their hearts that public schools are the chief, if not the sole, determiner of individual and national success – that schooling is the great equalizer…. Reform is important, and it can improve schooling. But events outside of school weigh far more heavily in shaping lives (Cuban, 2022)”1

Generations of educators have devoted their lives to making the institution of the public school into a pillar of democratic governance and societal well being. For all of United States history, however, public school has moved from one level of governmental neglect to the next level, two steps forward, one step back, until we arrive at today—the day after the National Assessment of Educational Progress presented the latest dismal results from federal tests of students’ knowledge of U.S. History.

In the beginning, American education was a private affair for the well to do, often the work of elite tutors, or it was the work of charitable groups pooling resources to teach the Bible. Reformers like Horace Mann believed in his heart in the Common School Movement during the years before the Civil War in an effort to convince government to fund basic education for every child. Eventually, political support connected public school to local public finances after the Civil War. Still, in 2001 George W. Bush was looking for a standardized way to leave no child behind.

Until the late twentieth century public schools existed with no strategy for fair and equal distribution of finances. Inequality of local schools was directly related to inequality of local property values. A U.S. Supreme Court decision in 1896 affirmed the legal basis of separate but equal as policy for a wide range of public settings, from rail cars to opera houses, permitting racially segregated public schools, and equal did not mean fancy. No remedy was attached to the verdict.

A different Supreme Court reversed that decision in 1954, finding that racially segregated schools are inherently, invidiously unequal. The remedy, however, had nothing to do with equality of funding or qualities of schools and teachers. Instead, integration through transportation using busses was the reform of the day. Transporting black children to white schools in a country with a deep and entrenched racist foundation meant calling out the National Guard.

Inevitably, a decision in a California case, Priest v. Serrano in 1972, outlawed gross inequality in funding, stopped financial inequity hiding behind white picket fences in the suburbs of Los Angeles and Sacramento while Compton smoldered and Watts lit up in anger and frustration. Progress was made. Nonetheless, in a country that has achieved equitable funding and integration in theory, public schools stubbornly produce unequal outcomes. Something is wrong.

*****

Equality in school as a footing for a good and decent life changed from a dream deferred to a possible reality in 1865 in Alabama, in Mississippi, in the failed Confederacy, on the courageous votes of emancipated and newly enfranchised black citizens (du Bois, 1934), who stepped up to the ballot box and got elected to local and state offices in droves just as they had stepped up for military service during the War. Black leaders laid the legislative groundwork for local taxing authorities to build schools to serve all children. And build they did.

But the slave oligarchy would not go gently into that good night. The legend of the Lost Cause took hold; the great claw back of equality commenced. Legal authority to levy taxes and build schools newly enfranchised voters seized after Appomattox was taken away from them by night riders, ballot box restrictions, suppression, and contract labor laws.

Sometimes events outside of school weigh more heavily than school in the shaping of lives. But the idea and legal precedent for public funding had taken root forever.

Progress in the dark.

*****

A link between state tax money and public schools was enshrined in State constitutions in Southern states readmitted to the Union during Reconstruction and became universal. State governments were good at arithmetic. The power of the State to impose a measurement mentality in public schooling arose from advances in statistics and standardized tests at the end of the 19th century and fed the emerging scientific management of schools by analogy with factories and assembly lines.

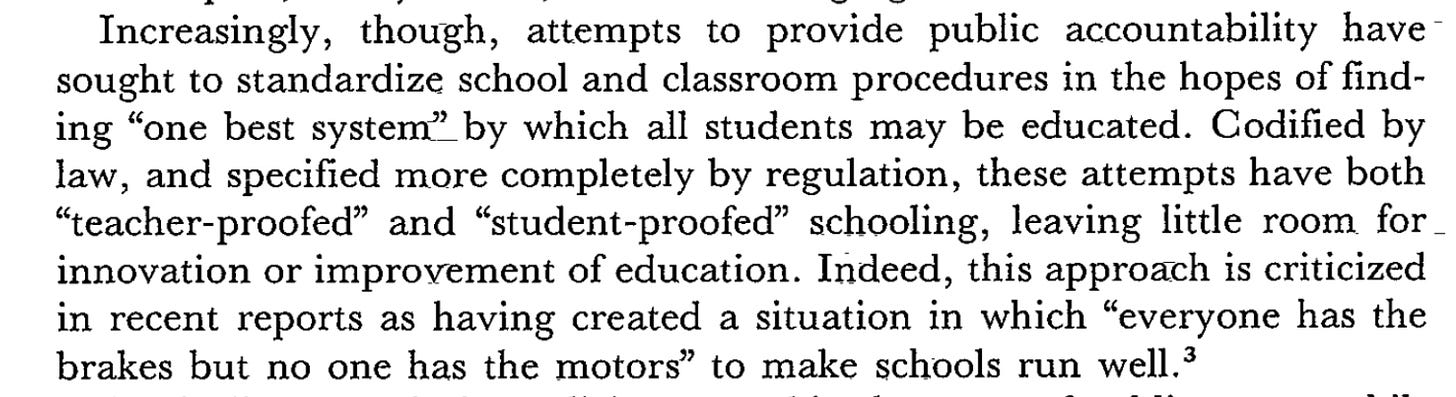

Measurement has intensified since Serrano v. Priest in 1972 to hold school administrators accountable for policy fulfillment: “The question is whether measurement and data-focused interventions are the best way for teachers and districts to accomplish urgently needed instructional transformations” (Shepard, 2020).

California in 2023 has fine tuned a school finance strategy intended to achieve equity through allocating more dollars to high-poverty communities than to affluent areas. Schools are required to give evidence of the proper use of those dollars.

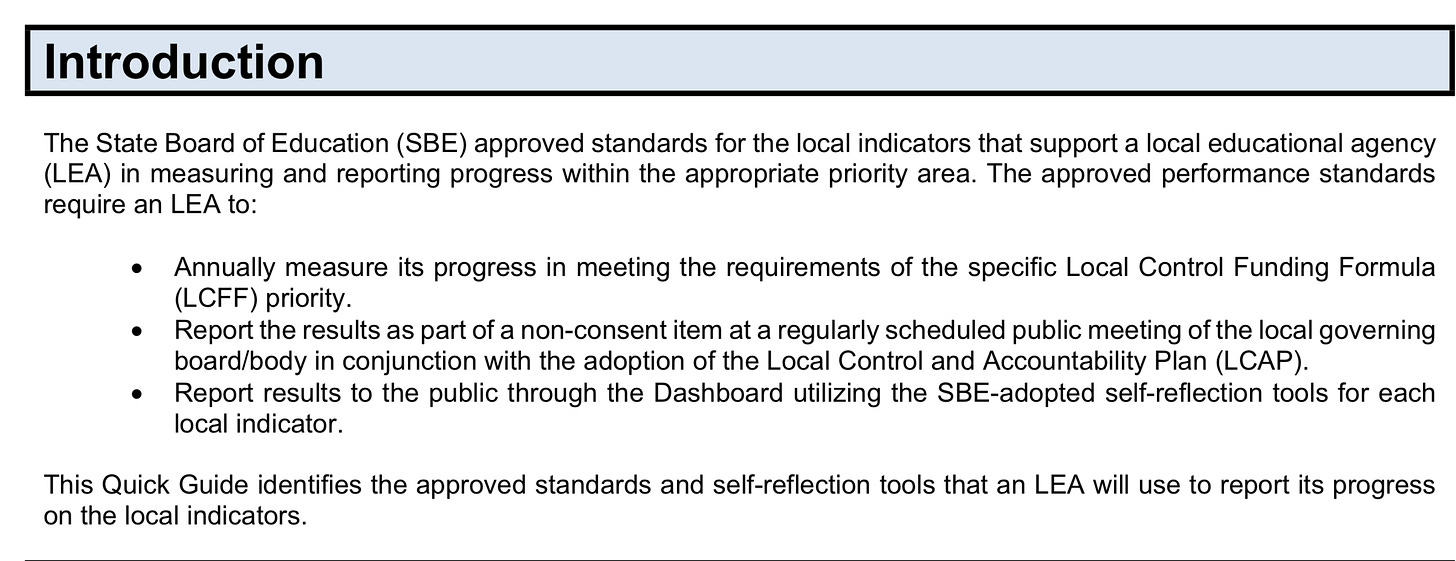

The State speaks to schools in a bureaucratic stance spelling out annual reporting requirements to LEAs to hold them accountable for spending the extra money where it will do some good, demanding proof, for example, that every child has access to curriculum-aligned materials and appropriately credentialed teachers :

The State reporting plan makes no request for qualitative data and collaboration—just the facts and figures detached from the lives of children. I could imagine language like the above being used in oversight of, say, a factory. The required “self-reflection tool” in California is a good idea distorted in the labyrinth of bureaucratic surveillance. Witness:

Here are three standard indicators of compliance required in the California annual progress report (see the following excerpt). One approved indicator of progress, “students have access to curriculum-aligned instructional materials,” makes good sense in a factory model. But it strips from teachers their professional prerogative to answer the curriculum-alignment question for themselves. Worse, it requires that money is spent on materials many teachers find counterproductive.

To reach their highest level of effectiveness teachers must have the professional prerogative to select materials and with colleagues to evaluate materials in terms of meeting the needs of their learners. Using externally aligned materials encroaches on an important part of teaching and makes local knowledge and collaboration optional.

Two steps forward, one step back.

*****

The 1960s ushered in a period of profound social and cultural change in the United States in the wake of the Civil Rights movement. Just as a great wave of black voters changed the complexion of state legislatures during Reconstruction, the Voting Rights Act in 1965 unlocked another surge of unmarginalized power that leveled the playing field a little.

In 1969 the Council of Chief State School Officers (CCSO) published a history of significant issues that emerged across the States’ separate public school systems since 1900 written in chapters by well-respected scholars to examine and explain the many ways State departments of education were meeting their panoply of obligations, perhaps the first national study of modern public school management.

Two chapters in the CCSO report in particular focused on processes states used for negotiating a state curriculum (chapter 5) and on protocols and practices for teacher certification (chapter 18), which will be discussed later in this post2.

By 1969 States had not figured out a way to coalesce thoughtfully on a state curriculum, let alone a national curriculum. By 2010 they still had not figured out how to engage stakeholders meaningfully in the hard work of mapping a relevant curriculum, but 46 of them signed on to the Common Core State Standards anyway.

Teacher certification was a patchwork of protocols and traditions forged state by state. Conceptual progress has been made on this issue very recently, and if the measurement mentality Shepard (2020) decried with its standardized stranglehold on education is restructured, real progress is within reach on this front.

But first in priority, schools needed funds for basic infrastructure and for teachers. The following excerpt from 1969 summarizes the mechanism whereby States slowly, reluctantly met their responsibilities for providing public schools the funds to carry out the education of the great unwashed. Witness from the CCSO panel report from 1969:

Irresponsible and nonresponsive local officials were on the way to extinction. Beginning in 1972 with the California Supreme Court decision in Serrano, which called out disparities in school finance arrangements depending on zip code, major restructuring of local and state finance formulas led to the refinement of Local Control of Funding legislation of 2013, discussed in more detail in an earlier post in this space.

Dominoes began to fall in school finance law leading to entire state school systems being declared unconstitutional by state Supreme Courts. Appalachian schools, separate but equal, looked and felt very different from Louisville schools until a 1989 Kentucky Supreme Court struck down the status quo and created meaningful reform, for example.

Here is language from the California decision in Serrano v. Priest, the first domino to fall, that acknowledges and condemns the reality that events outside of school shape lives more so than events in school differentially:

“We are called upon to determine whether the California public school financing system, with its substantial dependence on local property taxes and resultant wide disparities in school revenue, violates the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. We have determined that this funding scheme invidiously discriminates against the poor because it makes the quality of a child's education a function of the wealth of his parents and neighbors.”

There’s that word “equal” again, here conjoined with the word “protection.” Could it be that public schools could not be the great equalizer in the absence of Constitutional protections? Given this history of differential support, is it any wonder the State Board of Education in California would require annual reports to make sure that increased funds intended to be used to improve public schools serving poor children are actually used in that manner?

But isn’t there a better way to do it than requiring the purchase of curriculum-aligned materials approved by bureaucrats?

*****

Logically, free public education must by modus ponens inherently have the potential to equalize people and opportunities outside school where real life unfolds. Cuban seems just plain wrong. Human learning can surely pass from the classroom and shape lives outside of school.

Why else would every slave State have passed laws forbidding school for slaves if not to unequalize children’s potentials? Why else would Socrates have been poisoned by the State if not for his potential as a teacher to evoke critique of those in positions of power—to equalize?

If public school is such a weak institution as Cuban insists, oppressive societies bent on keeping people in castes would have no logical reason to twist or starve or restrict public schools. If inequality in school has a positive valence in the calculus of capitalists, must it not be true that equality in school could have a positive valence in shaping the lives of the poor?

Afghanistan made great strides in educating women during the first decades of the 21st century under more enlightened influences than the Taliban, but with the recent return of sharia law to the government, a wall has been erected again between women and their drive to learn and self-actualize in schools.

Why else, except for a belief in schools as life changers, would UNESCO, commit to step in, to continue to provide structured opportunities to learn for women in a male-dominated society which understands all too well that schools are “the great (un)equalizer”:3

“Since August 2021, UNESCO has shifted its interventions to ensure continuity of education through community-based literacy and skills development classes for over 25,000 youth and adults, including 60% women and adolescent girls in 20 provinces. Its advocacy campaign “Literacy for a Brighter Future” reached out to over 20 million Afghans to increase public awareness of the right to education for youth and adults, especially women and adolescent girls.”

*****

Sarason (1992) documented the predictability of failure in school reform in American history. But Sarason did not argue, as Cuban does, that reformers should accept the limits of schools and stop trying to leverage schools as a humanizing resource. Cuban doesn’t know that we haven’t finished making public school what it can become.

Reform will certainly fail until we change how we think about school, until States like California stop speaking to LEAs from an authoritarian, bureaucratic stance rather than in collaborative terms. State departments must be held accountable for their work as well.

Sarason offered a path forward through the reform wilderness: Change the vision. Schools past and present have been built to serve the needs of adults using scarce resources begrudgingly allocated to them. Things will change, according to Sarason, when schools are built to serve the needs of children.

The implications of a commitment to children are wide ranging, thoroughly explored in research discussed in books in the field of reading like Allington and Cunningham’s Schools That Work. A vision grounded in research is within reach.

No matter how one looks at it, teachers of today in the best circumstances work for adults in a semiprofessional limbo, and accountability measures often hamstring them from fully deploying their professional wisdom on behalf of children. They are positioned as subordinates working for administrators.

Reformed schools will position teachers as administrators, as professional practitioners working expertly to teach children to self-regulate their learning, as professional mentors working to develop novice teachers into the leaders with demonstrated and deep expertise. Pedagogues and pediatricians will join hands as professionals in a Science of Pedagogy and Physical-Social-Emotional Health.

*****

Fortunately, our history abounds with larger-than-life school reformers who did indeed believe in their hearts that schools are inherently powerful institutions that can reform themselves in a democracy and improve lives for all Americans.

From the ashes of the Civil War in Southern states under military occupation (du Bois, 1934), the idea of equity motivated newly enfranchised African-Americans to exert political muscle. Their first priority was education as a bridge to economic freedom,

The idea that knowledge and skill are good things for all in community, that school is the place to learn, that teachers ought to be prepared for teaching a curriculum, that children ought to attend classes instead of laboring in the mines or the fields—these ideas offered a way out of the nightmare of slavery.

Cuban is sadly right with respect to the unfathomable weight events outside of school can bring to dismantle the plans of school reformers. Federal military governors were pulled too soon from the former Confederacy in the mid-1870s, the result of capitalist compromise, and separate but equal became policy sanctified by the Supreme Court in 1896.

But the idea of publicly financed school had grown roots. In fact, public schools have steadily raised the level of consciousness, knowledge, and participation in public life of millions of United States citizens over the past century and a half. To argue otherwise is to be willfully myopic.

*****

Struggles for control of the curriculum have and perhaps always will take place and attract the attention of parents, employers, laborers, reformers. The certification of teachers has historically also been a focus of attention for reform state by state, though changes have happened by fits and starts. One might argue that the curriculum and the certification of teachers are the twin engines of the public school, turbocharged by the university.4

Concepts of the Curriculum, perhaps more than any other aspect of common schools, is by nature contentious. Darling-Hammond (1989) argued that policy needs to spell out discursive structures that mediate this contention and allow voices of all stakeholders to be heard to revise curriculum as circumstances in society warrant.

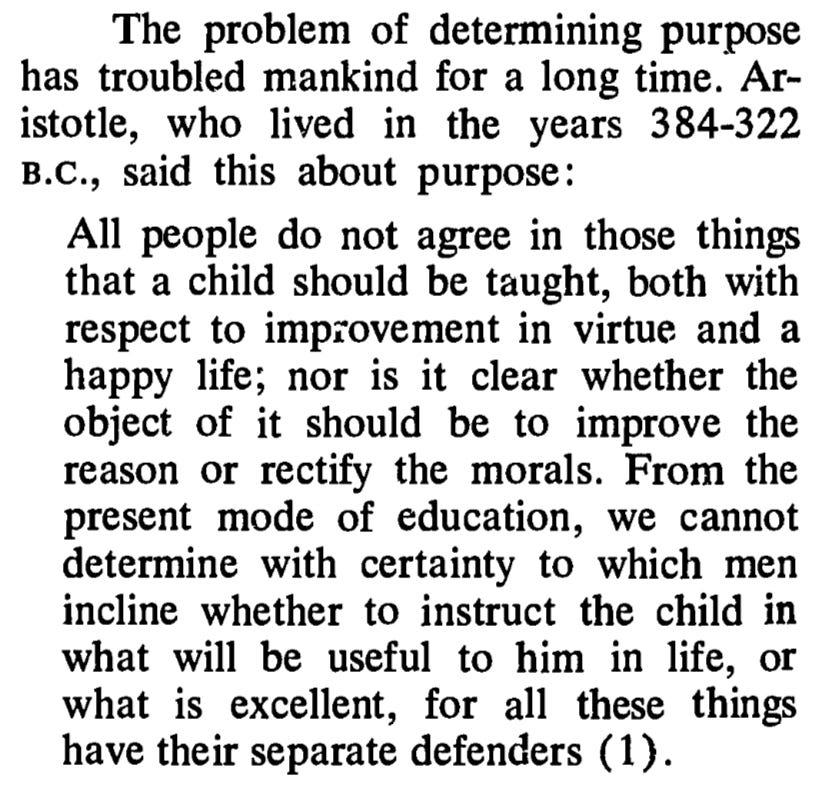

The author of Chapter Five in the CCSO report, writing during the Nixon era, captured an ancient sentiment and theme at the heart of curriculum contention familiar today. Witness:

In 2010 the same body of officials which produced this 1969 report, the CCSSO, also played a role in bringing forth the Common Core State Standards for literacy and mathematics, later expanded to include other disciplines. The separate defenders of the useful vs. the excellent came together in these standards under the rubric of college and career readiness, a deft political move that evoked high praise for David Coleman, as we have seen, the Core architect, from then Florida Governor Jeb Bush, for getting 46 states to set aside their differences and sign on.

Perhaps the setting aside of differences is the best that can be hoped for in polarized times. The Common Core movement was not about school reform. It was a political compromise masquerading as reform during a time of stagnation. Repurposing these standards with major revisions is a significant project for the future.

Progress is coming.

*****

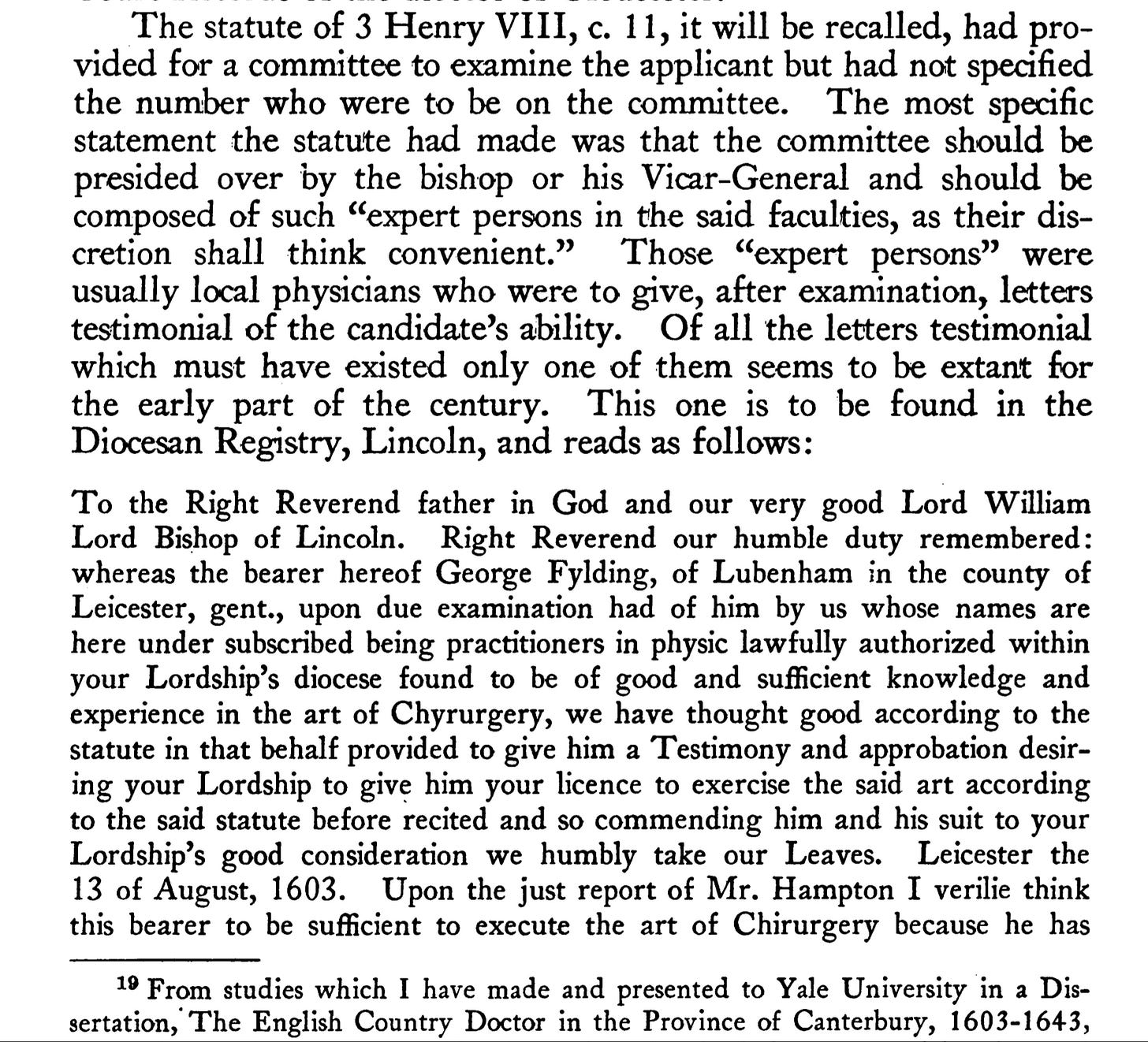

Teacher preparation and certification, according to the CCSO 1969 report, remained a work in progress. In contrast, a process for certification of medical doctors and surgeons in England was settled in the early 17th century.

Admission into the ranks of legitimate physicians with the right to practice depended on being examined by legally qualified physicians in good standing.5

Who possessed the expertise to certify a physician was an easy question. Why, physicians! Those who proved themselves through their good work to have what it takes to be a good doctor! They should examine physician candidates.

The King faced a pressing problem. English residents in cities and villages were going to so-called physicians who were killing them. Anyone could put out a shingle who could sharpen a knife. The need for identifying and certifying practitioners who actually knew what they were doing had grown acute.

Long before the invention of standardized testing, the English authorities devised what we now call “professional accountability,” that is, investing professionals—those who have mastered complex knowledge and skills and can do the work successfully—with the power to admit practitioners to the profession, to license them, and to hold one another as peers accountable. There would be no requirement from the King to practitioners for annual reports using required bureaucratic self-reflection tools.

That’s not what happened with the certification of teachers in the United States. Witness the CCSO report from 1969:

*****

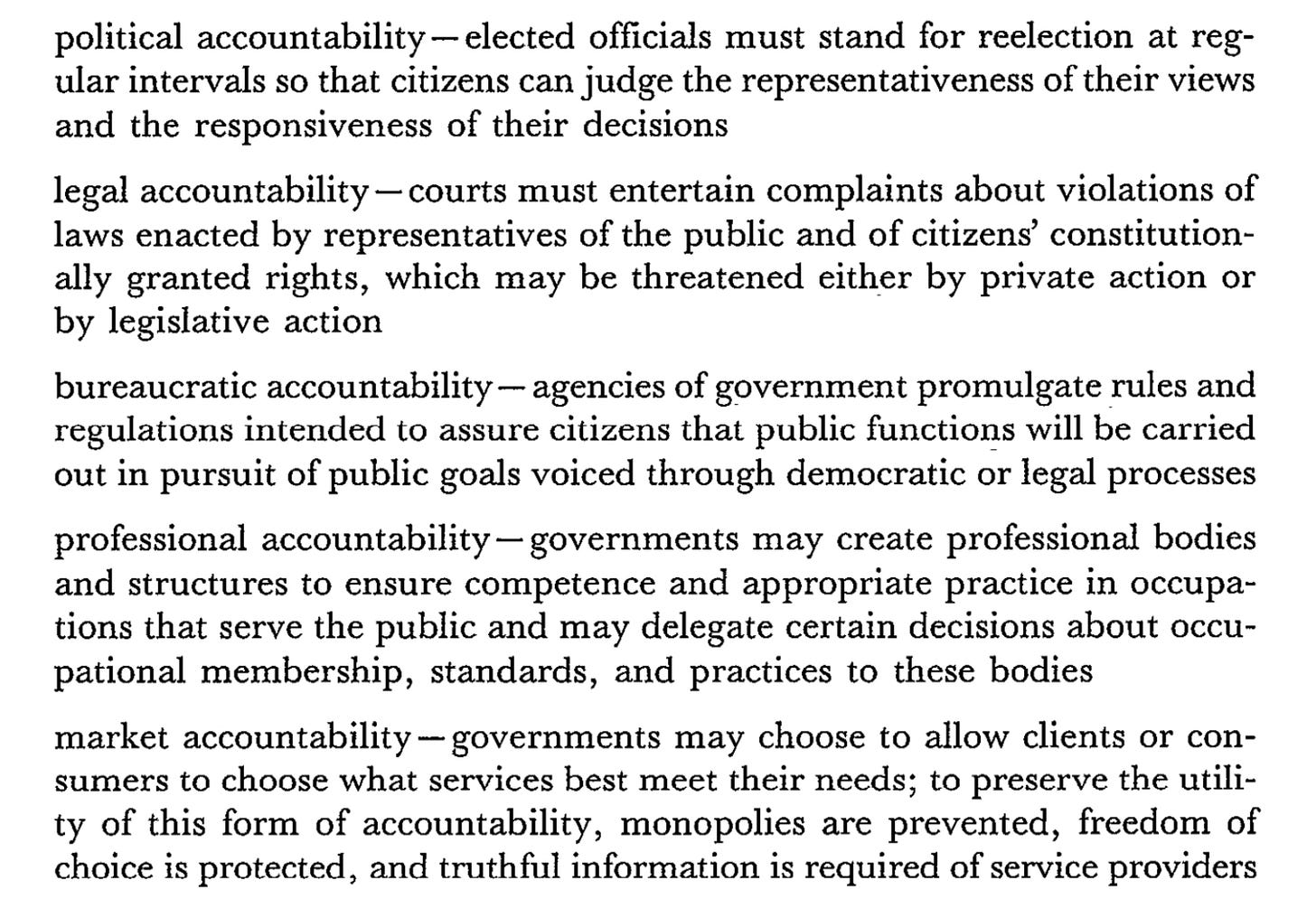

Darling-Hammond (1989)6 framed the issue of professionalism in the field of teaching as a lever for making deep changes of the sort Cuban (2022) might call pie in the sky. Darling-Hammond called for creating professional development schools by analogy with teaching hospitals as a location for clinical education in up-to-date expertise and state-of-the-art competence in the education of teachers. She spelled out five types of accountability interacting in United States society, and the wrong type still is applied to teachers:

Take a look again at the California instructions to LEAs for preparing annual accountability reports for an example of bureaucratic accountability. The State is the King, a non-expert, requiring quantitative reports and standardized assessments because that’s what bureaucrats do.

Darling-Hammond (1989) argued for professional accountability. Using language that brings to light the fallacy in Cuban’s logic, i.e., that events outside of school are so much stronger than events in school, she pointed out that the system itself was (and still is) moving in the wrong direction; if schools are weak, strengthening teachers through effective preparation and giving them the power to practice unencumbered by bureaucrats is the answer:

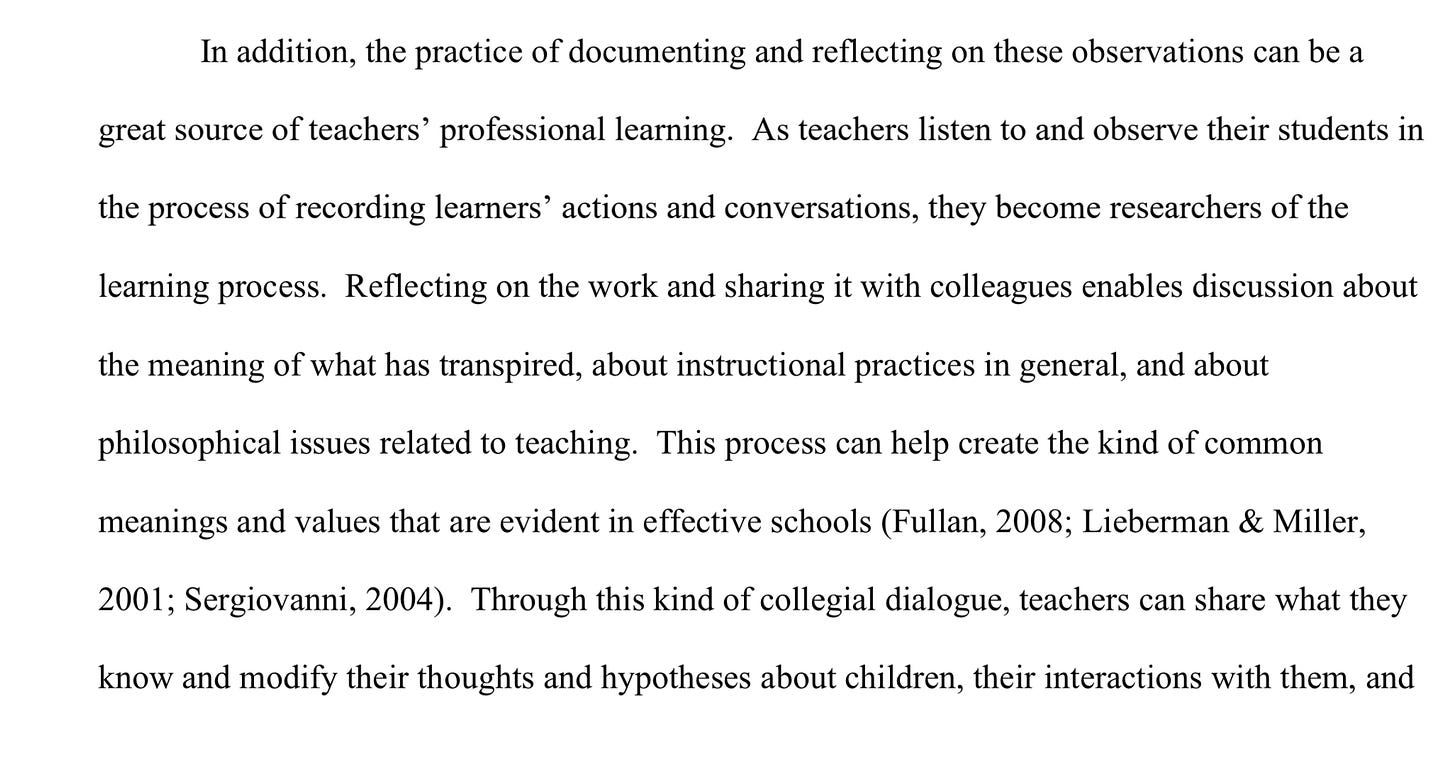

As part of a longstanding agenda to change the role and responsibilities of practicing teachers in public schools from supervised semi-professionals evaluated externally into professionals held accountable by peers like medical practitioners, Falk and Darling-Hammond (2010) advocated for carefully structured documentation practices in professional communities for certifying teachers, for induction into practice, for professional learning, and for advanced certification.

Beyond relying on expert practitioners for assurance of competence rather than the machinery of a bureaucracy, documentation protocols have the added benefit of amplifying teacher expertise over the years:

Note that Darling-Hammond is calling for policy measures that meet Sarason’s (1992) test: Does this reform emerge from a vision of what is good for children, not what is good for adults?

Large pieces of Darling-Hammond’s remarkably consistent agenda over several decades have become staples of regular practice in some states with robust preservice performance assessments by way of portfolios scored by teachers, structured self- and peer-assessment during the first two years of induction into practice, and a self-assessment system grounded in peer assessment leading to recognition of unusual accomplishment in the field: the National Board of Professional Teaching Standards. But the prize—professional peer accountability in public school credentialing and teaching protected by federal legislation—remains elusive.

*****

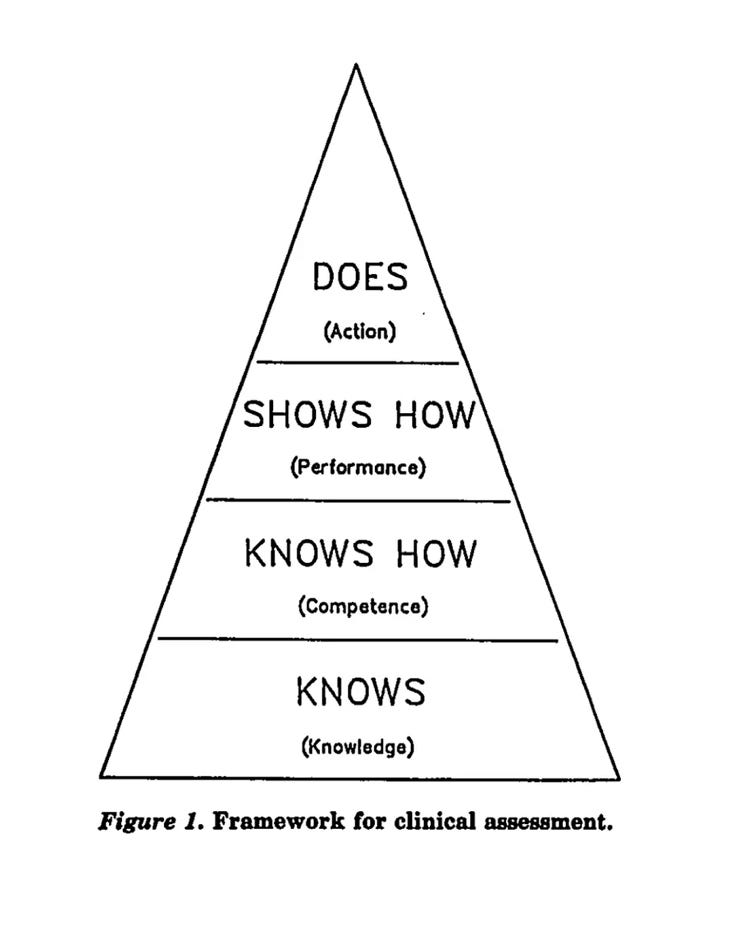

When I read Dr. Miller’s address to the Research in Medical Education (RIME) conference from 1990 I found cited in a 2018 study (see the previous post), I was struck by the pragmatism of Miller’s pyramid, especially in light of his choosing it for his speech to replace the notion of a “standardized patient.” The “doer” at the top of the pyramid must “do,” not simply know about or know how to or even show how to. Standardized patients, like standardized children, do not exist. It’s a serious mistake to practice on a real human being in a standardized manner.

In the flow of “doing” an expert job, important, unique differences in performance show up even among the most competent professionals. Doing a complex thing in real time at a consistently high level is existential, not theoretical or probable, and is best learned and evaluated by experts in the center of the community of practice who expect unique practitioners demonstrating unique competence. Keep the politicians and the bureaucrats away. Shepard (2020) would say most emphatically keep the measurement experts at arm’s length.

*****

Public schools are ready for teachers to assume professional stature. But the field needs a clear mandate, an Act of Confidence from Congress, to authorize a transition from bureaucratic accountability to professional accountability.

What are teachers doing when they are teaching? What do they know? How do they use their knowledge? How do they build it? How are they thinking? How can professional learning collaboratives among practicing professionals structure opportunities to self- and peer-assess and engage in shared inquiry around a philosophic and scientific understanding of “doing it”?

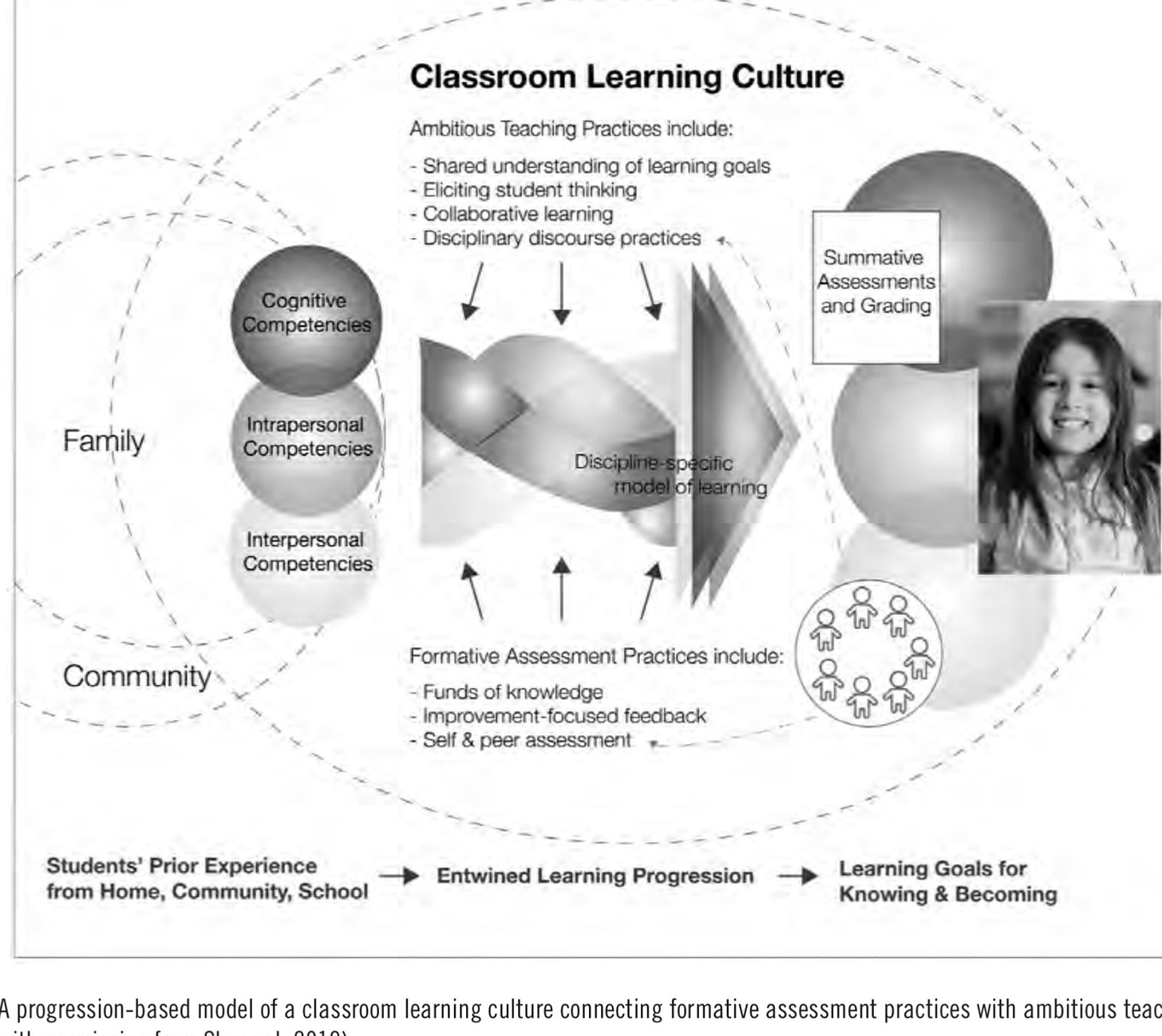

Shepard (2020) contributed a dynamic vision of the theater of practice in a conceptual organizer helpful in fleshing out the tip of Miller’s pyramid. Instead of the doctor’s office or the hospital bed, settings that have for decades been and are still scenes of structured qualitative research, the setting here is the classroom, and teachers are studying their own practices with their peers in collegial structures designed into their workplace:

Given all of the expertise teachers must develop to accomplish this “doing” on behalf of children, it seems as if holding them accountable for making curriculum-aligned materials (textbooks, worksheets) accessible in school and at home—the indicator used to hold teachers accountable to the Curriculum on the official required LEA self-reflection tool in California—completely fails to capture the essence of the work and distracts from a focus on learning.

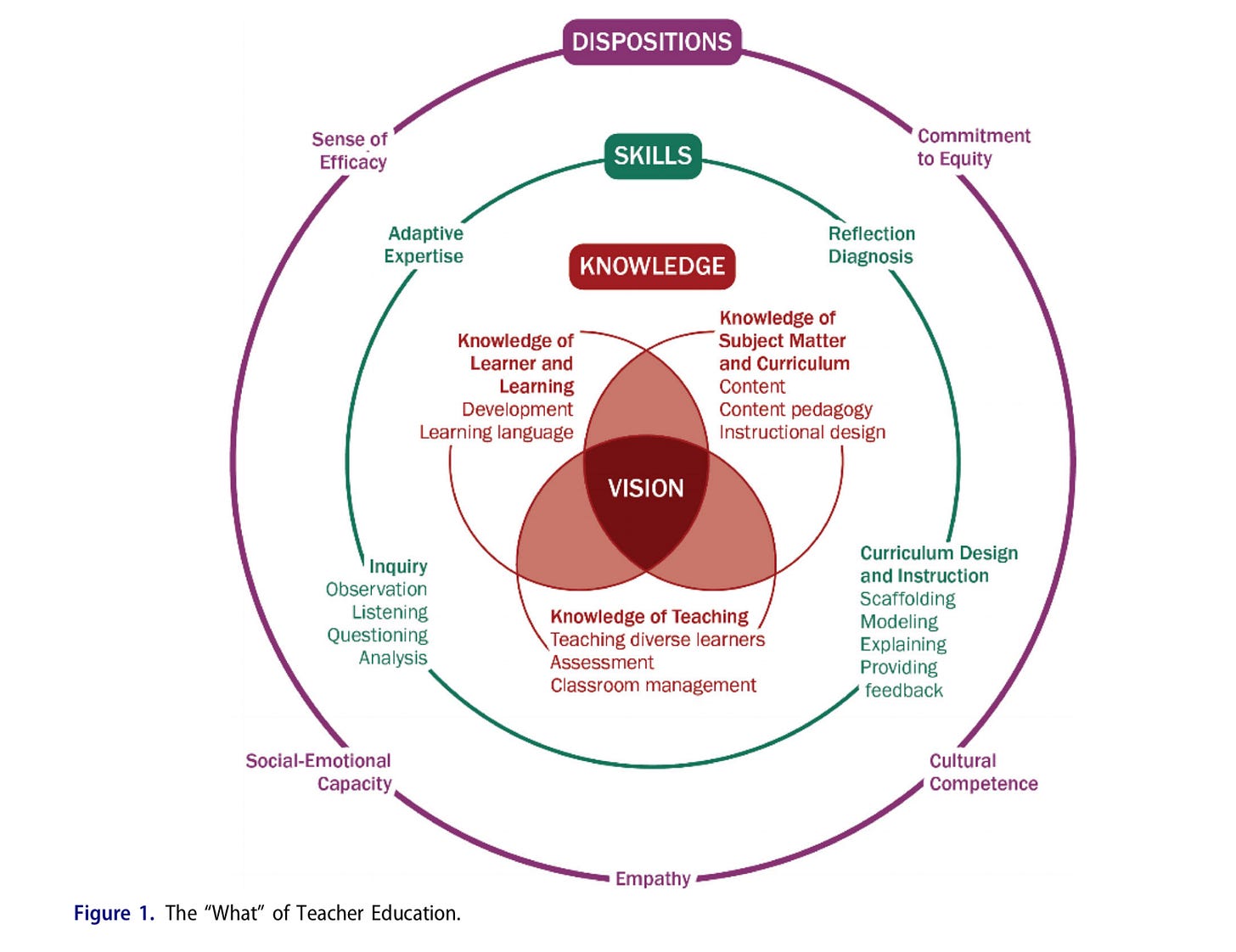

Darling-Hammond et al. (2023) zeroed in on the tip of Miller’s pyramid as well and created nested circles of relevance to teacher wisdom and expertise. The purpose of this figure is to communicate a conception of practice to guide teacher preparation to step into the theater of the classroom perhaps as Shepard (2020) depicts it as credentialed professionals with the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to begin “doing it” and to keep getting better and better at doing it on behalf of children:

Cuban argued that reforms like those spelled out by Lorrie Shepard and Linda Darling-Hammond might improve schools, but not be a game changer. What do you think?

“Schools don’t alter a capitalistic democratic society. They mirror it. And schooling is only one part of a person’s life. About 20 percent of a child’s time is spent in the classroom; the vast majority is spent at home, in neighborhoods, and other places with family and friends.” (Cuban, 2022)

https://ed.stanford.edu/news/schooling-important-it-s-not-all-important-larry-cuban-century-school-reform

https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/let-girls-and-women-afghanistan-learn#:~:text=Women's%20presence%20in%20Afghan%20higher,for%20all%20age%20groups%20combined.

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED031467.pdf#page=383

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2601475/pdf/yjbm00500-0001.pdf