Opening Willing Minds

The CLAS reading team started designing potential reading test items almost immediately in 1989 during the orientation session in Oakland while we discussed Judith Langer’s theory of envisionment-building and Louise Rosenblatt’s theory of aesthetic reading. Here is a sidebar from Judith Langer’s website (url is available in Beyond the Bubble):

Readers are envisionment builders, creating local envisionments as they move through a text, linking local to an unfolding global envisionment of the text-so-far. First, they step into a textworld, get a foothold, move through it, step back occasionally to reflect, and then step out to move to another text.

How would you assess how deftly a reader steps into a textworld? Can this be assessed? How do effective readers negotiate meaning at the cutting edge of comprehension? How do they use prior knowledge? How well do they keep control during times of ambiguity?

What would you see in the work of a really bored reader who is unusually strong in capacity? How can you disentangle interest and motive from capacity?

What kind of prompt will spark learners to show us what they do? Is it even sensical to think we can ask for evidence of aesthetic experience during an examination without destroying the experience and thereby the evidence?

Negotiations with the Other Side

ELAAC, the Board’s advisory group, agreed to consider the notion of enhanced multiple choice, mainly as a show of good faith. The test item would have options, one right, but then ask for written justification of the choice. Good justifications if wrong answers were given could earn partial credit. But still the item would be under the protection of the Knight of the Right Answer. The hegemony of the right answer would be preserved.

In the end there would be no pick-the-best-option on the reading test. The best option is what the reader takes freely. It struck me as poetic justice that this classiest of CLAS test items, the Open Mind, should involve an empty round circle, a bubble. I wish I knew who came up with the idea first or if it was imported. It was probably Fran, looking for a white crow.

Filling in the Bubble

It was called “the Open Mind,” and struck a nerve in the naysayers and the cynics: the Empty Mind, the Empty Head. After the test was implemented statewide, several parents spoke against it as an invasion of individual and family privacy. One parent was concerned that someone might misunderstand something and call child protective services and cause a family tragedy all on account of a reading test.

I recall a small group sidebar with Linda Chittenden, Fran Claggett, and Sheridan Blau after the work of field testing designs and analyzing student responses was underway where I began to offer what really was a naive suggestion—I opened with something like “well, if we want to see how a reader constructs text…”

Before I could finish, Sheridan uncharacteristically interrupted and moved my thinking to a new level: “No,” he said, “texts construct readers. You’ve got it reversed. We want to see how readers behave in the textworld, what they do with this space. There is no right or wrong. There’s nuanced, smart, there’s insight.”

He went on to talk about “brute signifiers” in texts—this text is about whales not squirrels—that are rightly or wrongly perceived (or not). And then what? You’ve been signified. You have to go beyond the simple facts and structure of the text, beyond a slavish attention to the facts of the text, to score above point three. Nobody knew what behaviors we might see at more advanced levels. The most important trait turned out to be a willingness to suspend closure on an idea or inference, to tolerate incompleteness, to revise understandings as processing unfolded, to sit comfortably in confusion and challenge and improve unfolding envisionments.

Imagine you are a fifteen-year-old child in an urban school. In third period English you are handed a reading test (we’ll imagine a pen and paper test).

This test has no forced choices, no short answers. After an introductory section explaining expectations and giving specific background about the passage, you will read the passage, make notes or underline or draw arrows or sketches—show your work so we know what you’re thinking or wondering or unclear about—as you read.

Once you finish you’ll write responses to some open-ended questions. Later, you’ll be assigned to a small group to discuss the passage. Then you’ll write an essay.

You open the test booklet and read the title: “The Lottery,” by Shirley Jackson. You read the story of a village that holds an annual lottery to select a person to sacrifice, who is stoned to death. The story opens with the piling up of stones and ends with a stoning. There is the suggestion that this ritual is carried out to help the crops. This year, Tessie, a mother and wife, gets the white slip of paper with the black dot.

Little did you know that the selection of this passage was contested. For one thing, the story is among the most widely read and taught short stories ever. Wouldn’t that advantage some, disadvantage others? The phenomenon of the ‘second read’ came to light. How many pieces of great literature exist that are read just once? Why insist on passages that no one has ever read? Why not aim for complex passages that reward multiple readings? Also, the story is heavy, depressing, hard to face. Why not something more cheerful?

So you finish reading the story you had no choice to read under test conditions, jot down a few thoughts along the way, circle a few words that catch your attention. You’ve not seen a test like this before. You’re just reading and thinking and making a few notes. The story is weird. You look up finally feeling bummed about the stupidity of the lottery and the unjust killing when nobody even knows why it has to be that way.

Your first official question: Now that you’ve read “The Lottery,” what do you make of it? You write: 1. The lottery was a stupid idea. I didn’t like what happened to the woman. I did like the story. Your second question is tougher: 2. If you could speak to the people of this town, what would you say to them? Use the thought bubble to express your message to them.

You feel a bit of outrage and write “Stop being stupid, people. You’re in the wrong town. Get out of there.” The next few questions are in a chart and ask you about specific words and phrases the writer used. So you go back to reread a few places here and there, mostly about the woman who gets stoned and killed, things from the beginning and middle. It wasn’t right. Thinking about these words and phrases help you piece things together about Tessie.

You write down in the chart why you think the author would use those words at those points. The last part asks you to explain how you see a quote fitting into the whole story.

The second to the last question stops you in your tracks. You see a bit of writing and then a blank circle that takes up half a page:

If you could visit the inside of Tessie’s mind the moment she sees that she got the slip with the black dot, what would she be thinking about? Use words, sketches, diagrams, quotes, whatever you like to show us what Tessie is thinking.

You find this energizing. You look again at what you’ve already put down, go back to the story briefly, and begin.

You divide the space into three areas. You draw some small houses with children in the yards in one area. In that section of her mind is a sun, a playground.

In another section you scribble the word MOB! and make the image wobble and jiggle, rocks flying from the letters toward a figure standing on the name Tessie.

In a third area she is angry. Her hair is standing up, her eyes and mouth are round and empty. She appears to be screaming in terror. The sky is filled with a dark cloud. When you look over it all you are surprised at your work.

The final question: Is there anything else you’d like to say to give us a good understanding of your reading of “The Lottery”?

Reality Shows Up

Incredibly, this assessment system still in its infancy was rolled out in 1993 and again in 1994. It was roundly criticized for its failure to educate the public about its radical nature, for its failure to implement smoothly, and for its failure to produce individual student scores. It could barely walk on its own.

Throughout its short life CLAS got negative press. The CLAS unit itself was blamed for problems far beyond its reach and charge. We know that CLAS was put on the shelf in 1994. Defund is the term these days. Not enough ink has been spilt to document this tragic whole-of-government failure to sustain a modest reform, in my humble opinion.

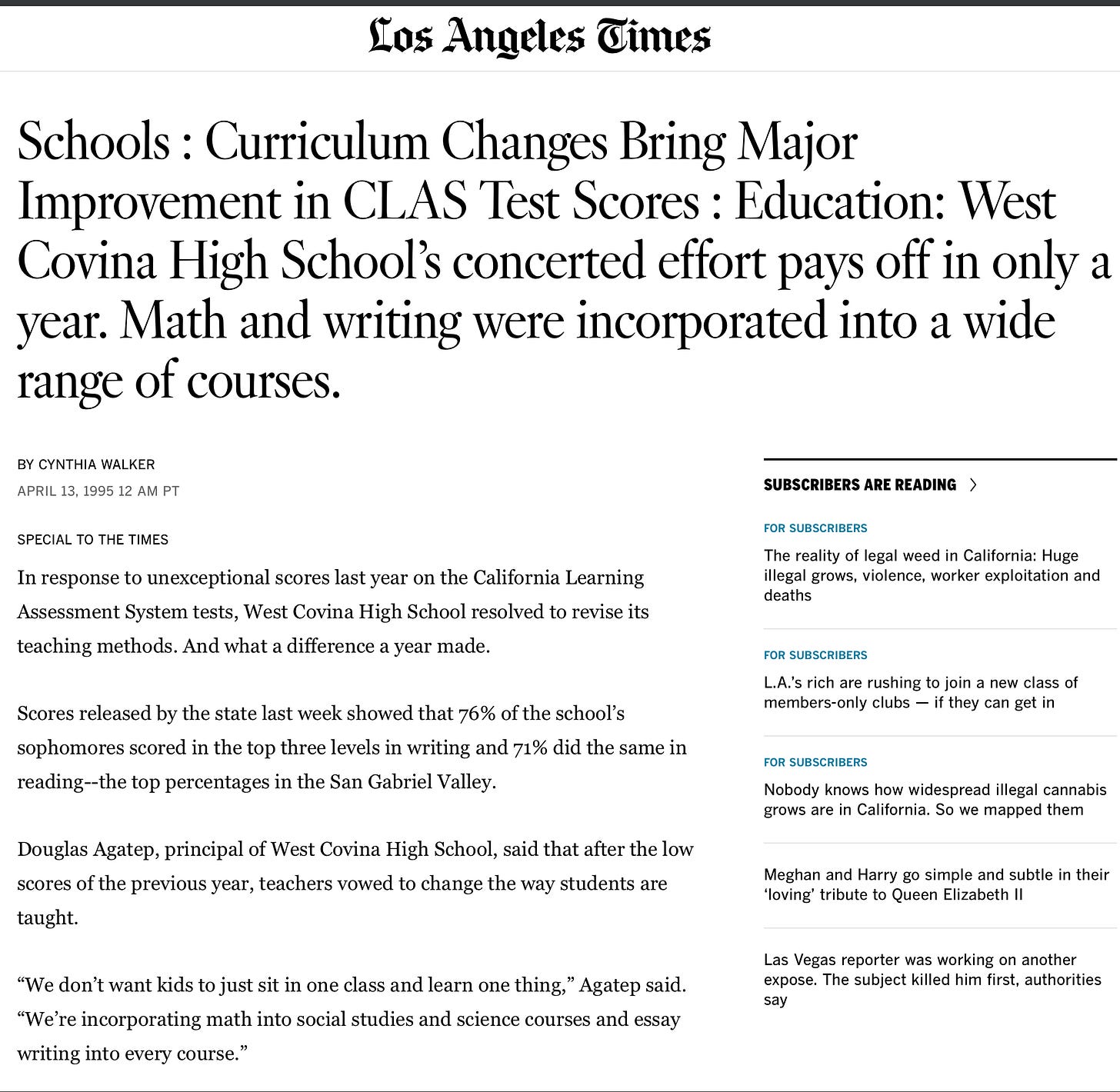

The LA Times blasted out a headline in 1995, after CLAS was dead, that belied the earlier squawking. West Covina High School served a working-class, diverse, multicultural, middle-class community, not an affluent, privileged community. But the school took CLAS seriously after it received some low scores in 1993. The teachers thought the test was much better than other tests and decided to work together to improve. Where many schools were scoring worse on CLAS than on bubble tests, this one did better. Look what happened when it retested.1

Continuous Improvement

CLAS reading tests included a scaffolded oral discussion among four students, who had read the same passage, intended to prompt students to look back to the story, co-create interpretive ideas, and point forward to a writing prompt.

The writing portion of the assessment system had been built in 1987 and was ready to go. Writing prompts could be loosely related to the reading passage or integrally related. Scoring rubrics for writing were aging well. The reading test design had been used to develop a large number of grade-appropriate tests, and a scoring rubric had been made. However, no progress was made on actually collecting data and assessing the oral work. To really improve pedagogy, assessment of whole literacy events, especially the talking and the listening, will offer valuable insights into a main location in school discourse for the social transference of mind through talk.

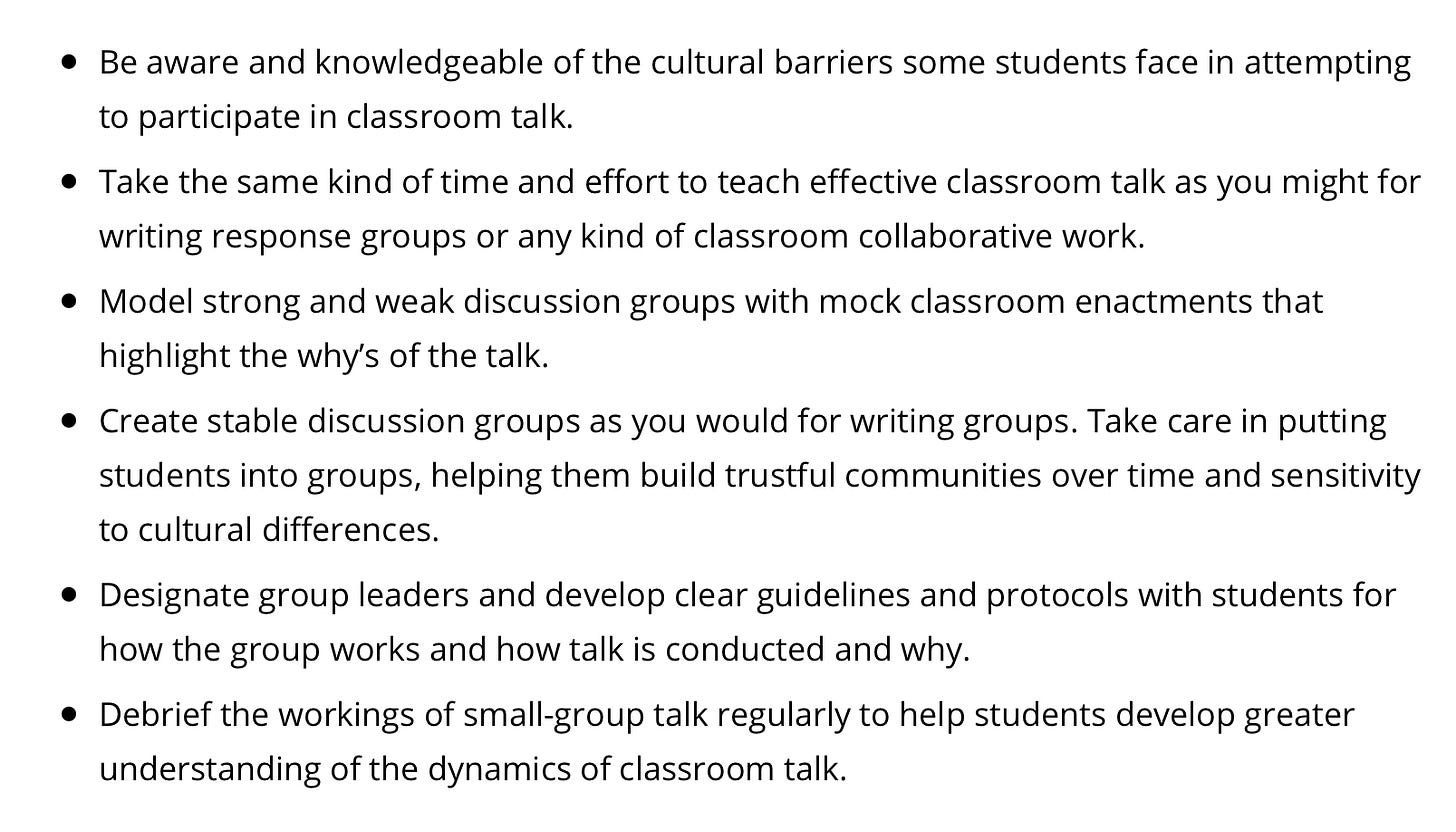

I’ve always remembered Carol Tateishi’s interest in the oral component of the CLAS test from my initial phone interview in spring, 1989, to determine whether I would be a fit for the design team. I was pleased when I found Carol online a while ago, still interested in orality in the classroom. She wrote a piece recently about classroom research she carried out to find reasons for the silence of Asian students in classrooms. Asian students just don’t talk much.

To find out what Carol learned, read her absolutely riveting post in which she describes how historical and cultural dimensions produce and normalize silence in public school classrooms (see note for the url “taking a chance with words” below). She distilled immediately useful recommendations I’m excerpting below that would have worked perfectly as both assessment and instruction in the CLAS authentic system.2

California made a conscious choice when it adopted the Common Core to place responsibility for resourcing and implementing assessment with districts, weakening the synergy that arises through large-scale projects. CLAS, though short-lived and thorny, could be a place to begin again to professionalize public schools in regional networks with a central hub divided between LA and Sacramento. Federal assertion of powers as a central hub may happen someday if the citizenry demands real accountability of the professional kind.

https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-1995-04-13-ga-54349-story.html

https://rethinkingschools.org/articles/taking-a-chance-with-words/