Systematic, Explicit Instruction in Racism: Florida’s 21st Century History Curriculum

Let the Good Times Roll

“No one should be instructed to feel as if they are not equal or shamed because of their race,” DeSantis said in a statement on Friday. “In Florida, we will not let the far-left woke agenda take over our schools and workplaces. There is no place for indoctrination or discrimination in Florida” (Solcyre Berga, Time Magazine, July 20, 2023).

Agreed, Mr. DeSantis. There is no place for indoctrination in public schools anywhere in the United States. My question: Why is Florida’s Board of Education not just legalizing but requiring both indoctrination and discrimination in its public schools? Florida’s State Academic Standards for Social Studies—2023 are available here. As I read these standards, the initial draft published in 2022 constructed curriculum objectives that changed the American story in subtle yet profound ways during its founding, its Civil War, and its Civil Rights era. As historians like Timothy Snyder have explained1, political movements through time are fueled not so much by history, but by the stories people tell about their history.

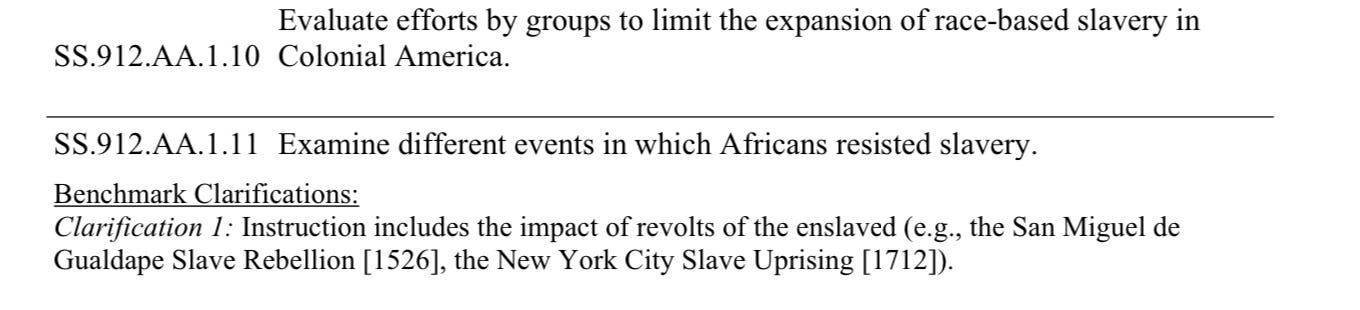

In essence, according the the story put forth in the Florida standards, the colonists even before 1619 had been coerced into using African slaves by the English monarchy. They didn’t want to buy African slaves; they could have done with indentured servants or by making laborers of indigenous people. Of course, most colonists recognized it as malevolent, but what could they do? Following the Revolution (which was fought over unfair taxation, mind you, which still goes on today) stout-hearted White men stood against the evil of slavery by installing into the Constitution the three-fifths compromise and a time certain for the end of the slave trade (1808). Mr. DeSantis and his School Board insist that Americans knew all along slavery cuts against promises of equality and justice. For example, consider the following standard, and note the clarifications added to the standards document recently in 2023:

In alignment with the argument that “the King made me do,” White children of today in Florida are taught to understand that all along White Americans tried to eliminate slavery. The clarification, however, is ambiguous at best. Are students to understand that the White man stood side by side with the enslaved to abolish the peculiar institution? Or that White people tried to do it the right way, through political action, while the slaves themselves got violent about it? How does one get clarification of the clarification?

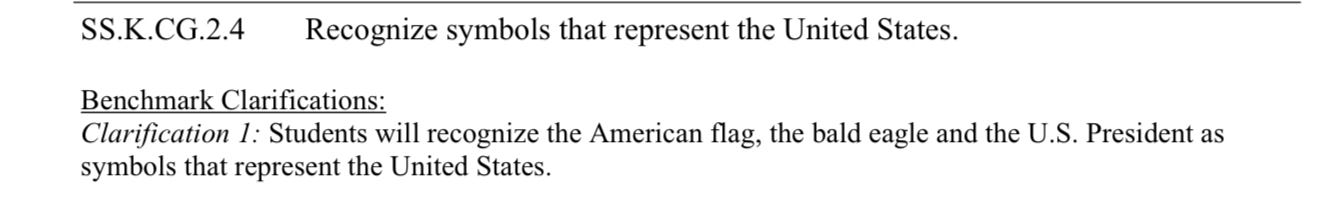

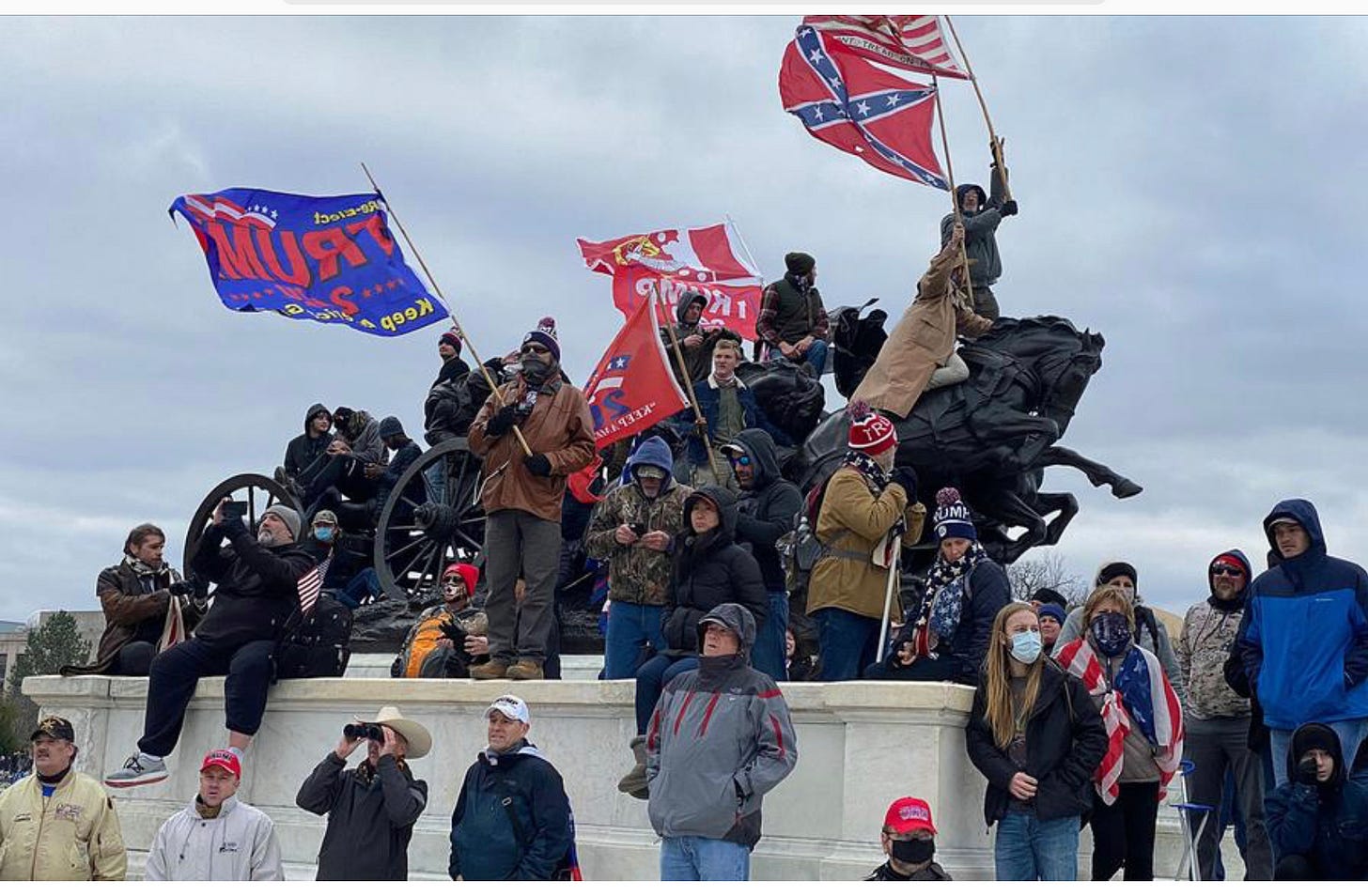

An especially fascinating standard has to do with “understanding symbols” and the place of symbols in the national narrative. Social psychologists have researched the role of national symbols across nations and cultures and across historical formations, including the role of the flag in Germany’s history, and have found that flags, according to social identity theory, serve the primary function of differentiating the country’s own people from out-groups and, though they can arouse positive feelings for a nation, can also heighten biases and prejudices. Another recurrent theme in this literature is the increased frequency of appearance and amplified salience of the flag during national identity crises. Here is Florida’s standard during our national identity crisis:

I’m not sure what exactly to make of the following photo as a pedagogical device (I’d need to sit with it for a bit) nor whether I could use it in class if I were teaching eighth grade history in Miami (historian Eric Foner could help us here to disentangle issues if we were a history faculty debating its risks in Florida schools), but there are clear linkages in the image between the Confederate flag, the American flag, the bald eagle, and the U.S. President. One can only hope this clarifying concatenation of the Stars and Stripes, the eagle, and Donald Trump wasn’t in the mind of the Board in Florida, suggesting that this U.S. President spelled out in reversed letters is to be revered. Witness2:

The uproar of the moment coming from the Florida Board’s clarifications of its revisionist history standards is particularly repugnant. In my view, admittedly oversimplified, I read the national story Florida wants to sell as follows: From the beginning, White Americans abhorred slavery. Early in the story, they were forced into enslaving Africans by a malevolent European aristocracy. Once the peculiar institution solidified into an economic way of life for the Southern states, White Americans fought to fix things and finally fixed the problem through a bloody Civil War no one wanted to fight. Reconstruction didn’t really work for a variety of reasons, including the incapacity of freed slaves. White Americans kept supporting their African American friends and neighbors through accommodations, doing the best they could. Finally, the Civil Rights movement but to bed racism. We got out Voting Rights Act and, voila, we reached Dr. King’s mountain top. No need for voting rights legislation. No need for affirmative action.

But now we keep telling our children the wrong story, insists the Florida Board. Racism is over. It’s wrong to tell White children they are responsible for this history. They didn’t do it. Instead, we should teach them about all of the great things African Americans have contributed to the nation and keep quiet about minor ongoing atrocities like racist policing, massive differences in educational opportunities, huge disparities in income and healthcare, and the like.

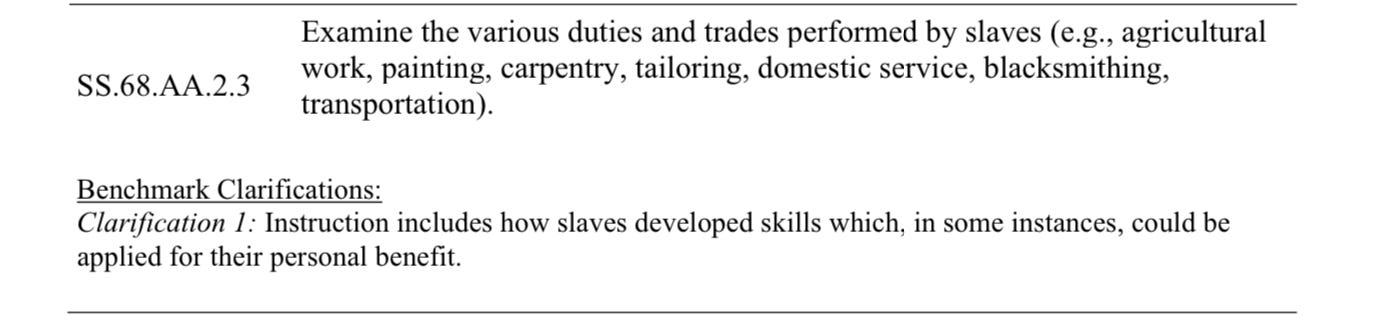

Embedded in this larger picture is today’s news cycle blip. People are incensed about a particular clarification, rightly so. Here’s the point of contention:

In fact, according to Frederick Douglass, slave owners were astute examiners of special talents and abilities among their slaves. It behooved them to train talented slaves to create art, to invent useful things, to make use of their gifts. Slave owners protected talented slaves from brutal working conditions in hot fields, not out of humanitarian concerns but financial, though there was no shield from the whip if they got uppity. Owners rented them out, sometimes letting the slave keep a small portion of their earnings when they felt generous. But these talented slaves had no intellectual property rights, no provenance over their inventions or creations, no inalienable rights to equal treatment.

To teach children that a small number of slaves learned skills for their own benefit during slavery is not just misleading, it’s factually wrong. It is pernicious, insidious, morally bankrupt to insinuate the idea that any slave owner had any intention of teaching slaves with unusually strong talents to use them for their own benefit—or would have permitted it if it went against the owner’s wishes. If a slave invented a tool, the invention was the owner’s property. If a slave created a beautiful ceramic vase, it belonged to the owner. If White people liked a slave’s singing, they would have to sing for their supper.

This clarification is disgusting.

I read recently that fewer people are going into teaching than the low mark reached in the 1970s. I have no special knowledge as to why, but sanctioned moves like the Florida Clarifications would make me think twice about working for a credential. It’s tough to see how serious teachers like those I worked would have the stomach for it. I find it hard to grasp how such a clarification, hyping the educational benefits of slavery, could spring to mind unless the committee so desperately wanted to make the White man the hero of the story that it would sell its soul to the Devil.

David Blight, who along with Eric Foner offer us the deepest understanding of Reconstruction and its aftermath consonant with W.E.B. Dubois, is worth digging into for an account of the vagaries of historical memory, especially in domains of knowledge like slavery in which the very idea of nationhood is breached. Blight is a well-respected and widely-acknowledged expert on Frederick Douglass who has trained a platoon of PhDs, and he is both meticulous and readable. The role of Robert E. Lee or Jefferson Davis as they impact us today, for example, has real, factual material underneath, yet historical memory being what it is, most of us would be hard pressed to discuss much more than a skeletal frame and, given demands on our bandwidth, rely on our inborn good sense to separate fact from fiction.

https://www.stripes.com/theaters/europe/657684.jpg/alternates/LANDSCAPE_910/Trump%20supporters%2C%20including%20one%20waving%20a%20Confedera

Thank you for addressing this. It’s a shame that there is such a debate on whether we should teach K-12 students biased history or reality. These debates have definitely deterred myself from going into 7-12 education, where teachers face significant restriction and scrutiny for how they teach history.