I’m searching for a way to respond to what I’m hearing in the YouTube below. One way would be to take on the entire theory of composition instruction underlying this presentation, not feasible in a newsletter post. Another is to ignore the obvious problems in the simple view of writing, a strategy I’ve always had problems enacting. A third is to wax sarcastic, the strategy I’m trying to avoid. Apologies in advance if I offend.

The Wisconsin Reading League chapter sponsored a book club around a work titled “The Writing Revolution.” The Reading League is a fairly new organization that has come together to hold public education accountable for its betrayal of America’s children through selfish, unscientific teaching practices from the dark ages of Whole Language. They had their hearts in the right place but their heads were wrong.

As I listened to the presentation, the presenters opened up a revolutionary take on writing process instruction actually arising from Alexander Bain’s work on the paragraph as an essay in miniature circa mid-19 century. See the NCTE publication Cross Talk: in Composition Theory (2003) for elaboration on Bain’s approach.

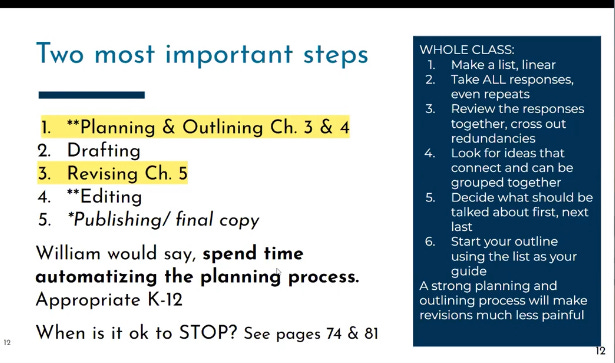

Eschewing the outdated notion that the writing process is recursive, not fixed and linear; that as writers mature they create idiosyncratic strategies that work for them; that writing processes vary depending on context and purpose; that the paragraph and its big sibling, the essay, don’t corner the market on written products, the new approach presents the process as a discrete set of stages, separable, teachable separately.

So what I learned about the history of composition theory in my doctoral program was all wrong. My professors fooled me into thinking writing instruction is more complex than it really is. My experience in the Area III Writing Project was illegitimate. Shift your eyes to the simple view, so sayeth the Reading League. This League identifies the emergence of scientific evidence for reading (and Writing by modus ponens) in 1986, the year Phil Gough published the Simple Proclamation.

It was gut wrenching, not because I hadn’t heard this view before, but because this Science of Reading movement has made such inroads into state legislation. I heard that my colleagues and I have been wrong all these years. All of the action research I did collaboratively to “reclaim the classroom” from the clutches of the simple view. The Reading League tent has turned the tables by penetrating state legislatures.

Writing teachers should have been teaching children to plan first in linear fashion, and planning involves outlining, which controls what can be written in a draft. I remember a study showing that when teachers required students to submit an outline with a paper, many of them wrote the paper first and then prepared an outline.

Outlining in the revolutionary view involves coming up with an idea for what your topic sentence should say in your paragraph and then the details. I’m assuming the process applies to the essay as well except that the top level sentence is now called a thesis statement.

If you read the right hand sidebar in the screenshot above, you’ll learn that planning makes revision less “painful.” I taught my kids that revision was the most exciting part—writers could talk with others about writing problems and opportunities, follow up on ideas that surfaced during drafting, draft some more as they understood more about why they were writing the piece in the first place. It never occurred to me that the reason for prewriting was to safeguard students from the pain of revision. So prewriting is the place where writers close an open mind to soften the blow of changing their mind midstream.

I’m not quite sure I understood everything completely, but I heard that I should have started with planning and taught the skill to mastery before I tackled drafting. Plan. STOP. Plan. STOP. After all, drafting involves spelling words and writing them in sentences, a task requiring massive demands on working memory especially if there is no role for temporary spelling. “The human mind can only take so much,” sings Bob Dylan. “You can’t win with a losing hand.”

How could we have expected children to draft without knowing what they would like to say in advance? How could we have worked so hard to help writers develop a sense of audience when they can’t yet plan a linear outline? Why would we invite them to bypass orthographic mapping and invent spellings just to write a poem? So much for drafting as a discovery tool.

The planning piece can be done with a whole class, skip drafting altogether, and scoot on into revising the plan. Imagine that. At least I think I heard that. There was some back and forth among the presenters and participants that got a little complex and confused my simple brain. For sure it is scientifically true according to the League that I could STOP instruction after any segment. Completing a piece of writing isn’t necessary. Publishing can wait.

The League sees some problems with the Common Core writing standards. The Core picture is righteous—the big ticket items are Bain’s argumentation, exposition, and narrative structures (eschew those traditional creative writing assignments). But the foundational skills required to meet many of the Writing standards are addressed in the Core in a fragmented manner, the writing scientists say.

According to the League, the Writing standards would benefit from a new detailed section on the skills that underpin all good writing, perhaps the guts of linguistic performance needed to move from spelling a word to constructing a phrase to generating a clause.. Until then fundamental skills can be found in CCSS sections other than Writing. For example, a standard under the foundational skills in the Reading strand… If you want to teach writing, you need to teach children to… decode.

I found just the reverse when I taught fourth grade. My reluctant readers turned on to reading gradually as they learned about agency through writing. But agency has no place in writing instruction. So sayeth the Simple View.

what no wave? wave is a description for something that is used to measure frequency -- particles are points, waves are cycles. Joyce pins word particles into the movement of a wave, beckett is especially cyclic... ✍️

I love breaking rules. Think of rules as being there to push up against -- in relation to mining for meaning, for finding unwinding, signing... even. Like Shakespeare does with fates in myths. Albeit deformed by post modern cut ups, three body problems, and principles of uncertainty as waves and particle. Cheers for the holiday.