School Reform in Arkansas

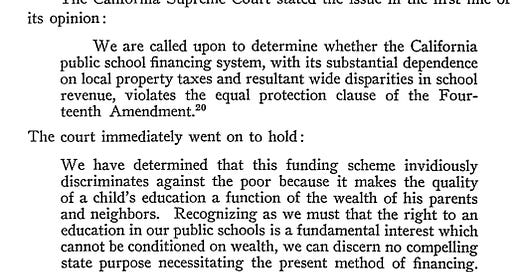

One might argue that modern public school reform began in earnest in 1971. Serrano v Priest came before the California Supreme Court that year, a case involving the constitutionality of school finance arrangements as they had been forever in the continental United States. Schools were financed first locally through property taxes, supplemented with state moneys raised through income or sales tax, and some modest federal assistance. Some of the poorest neighborhoods in the country had the worst schools despite paying the highest proportion of property taxes. Witness the judgment:1

The force of this decision echoed throughout the states with a cascade of similar cases decided in favor of equitable financing with significant implications for shifting relations of power between state governments and local districts. In 1989, for example, the Kentucky State Supreme Court found the state’s school system unconstitutional after 66 rural counties filed suit and battled the local courts. Instead of calling for a change in the funding formula as the sole remedy, the Court ordered the legislature to write and pass school reform legislation reaching deep inside the hidden curriculum. When KIRIS, the reform bill, was drawn up, there was a call for the design and implementation of a writing portfolio system as part of substantive reform, perhaps the first example of a combination of funding and testing as state-level restructuring tools.

***

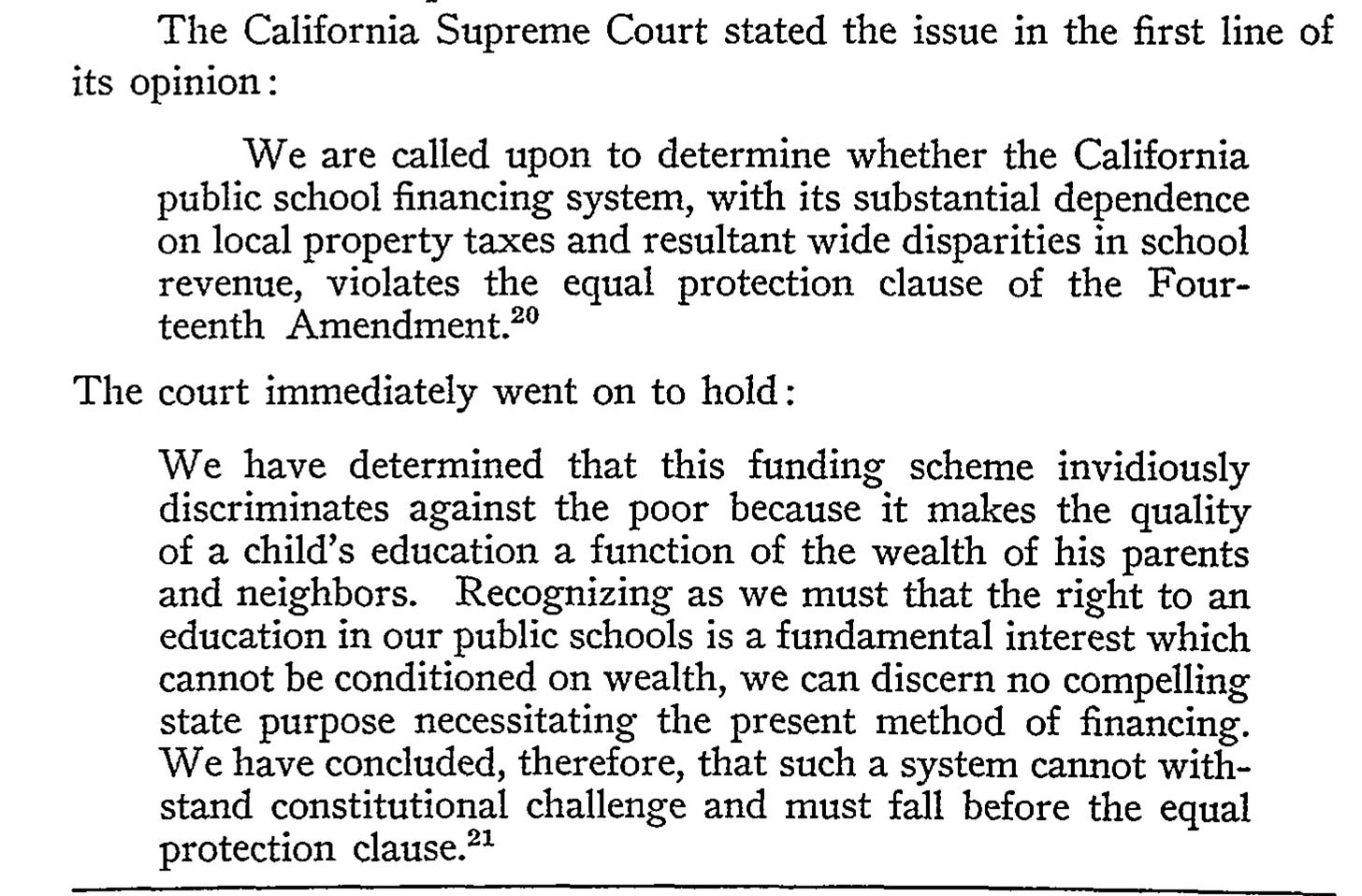

In Arkansas, not Alabama, a state law, the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA) requires the Arkansas State Department of Education to report a school index statistic with a rating of school quality. According to an Arkansas news outlet, the results from 2022 were less than stellar:2

As readers of ltRRtl know, Arkansas policy makers have responded to this crisis with carefully considered actions. For one thing, Governor Sanders, former spokesperson for then-President Trump, recently signed legislation prohibiting employers from requiring written permission from parents to hire their children in menial labor on school nights and weekends. For children attending school by day in one of the 32% of the schools getting a “D” or an “F,” the money they bring home from night work might in the moment be more valuable to them than being in school.

This is not idle prattle. Just last month, Governor Huckabee announced her education plan to include state funding for parents to enroll children in public, private and parochial schools or homeschool through a proposed Education Freedom Account. Rural counties are anxious about the demise of public schools as privatization with the right not to accept cost-intensive students with special needs as well as a release from accountability measures looms in the offing.3

***

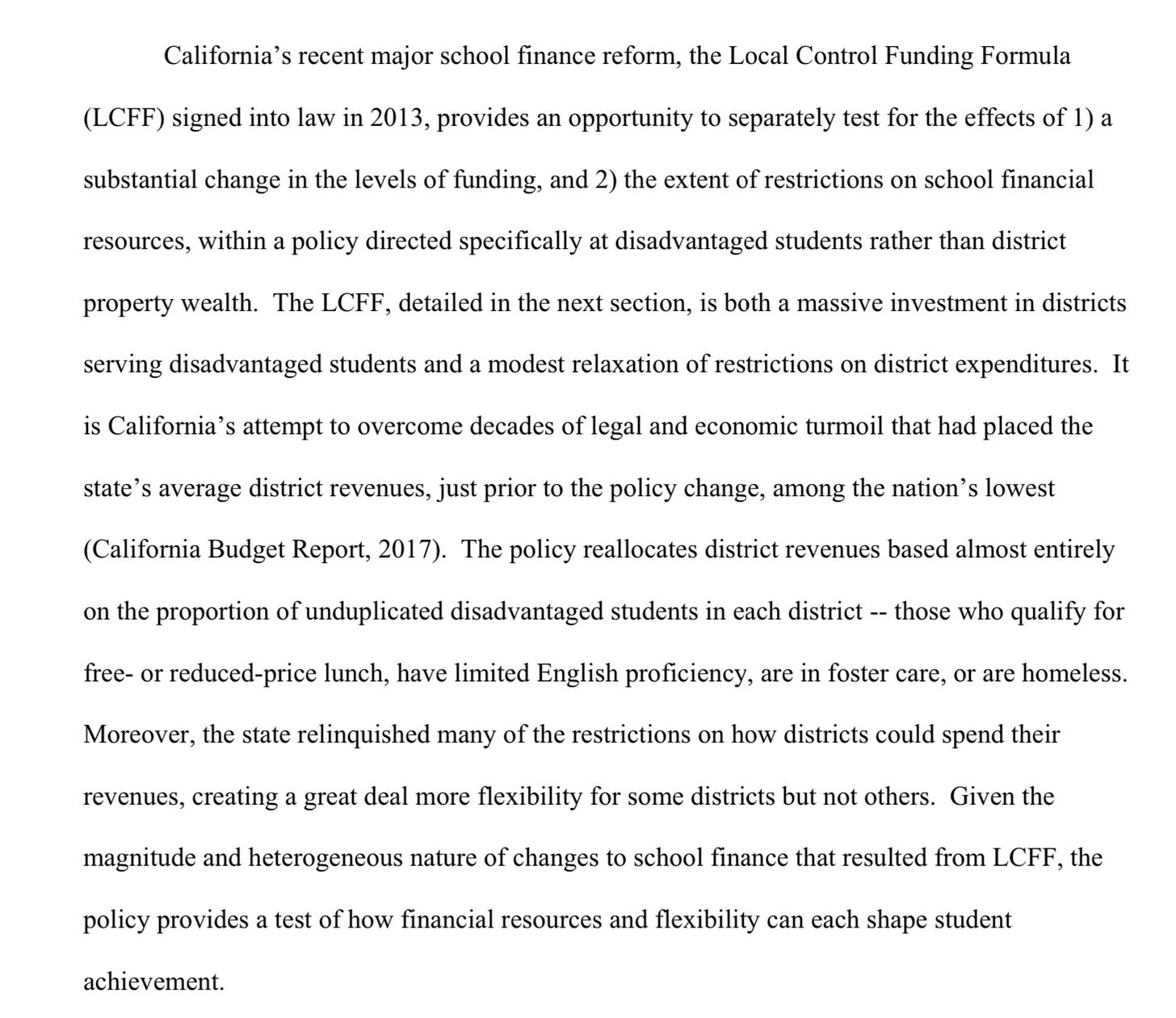

Arkansas is listed #2 nationally on an online list ranking states by how well they distribute school funds equitably among districts. Judge for yourself the reliability and validity of the source (if the method described on the site was followed and the data are accurate, the finding seems at least arguable in its own terms to me), and see if this conclusion triangulates with your prior knowledge.4 In contrast, this same report ranks California #48, which is likely not valid (cf. Tanner, 2018). Note that an equitable funding rank is not the same as per-capita funding rank; per-capita funding to remedy residential segregation varies in an inverse relationship with average residential household income. More per-capita funding, usually with restrictions attached (though no longer the case in California), goes to students living in residential segregation with less household incomes.

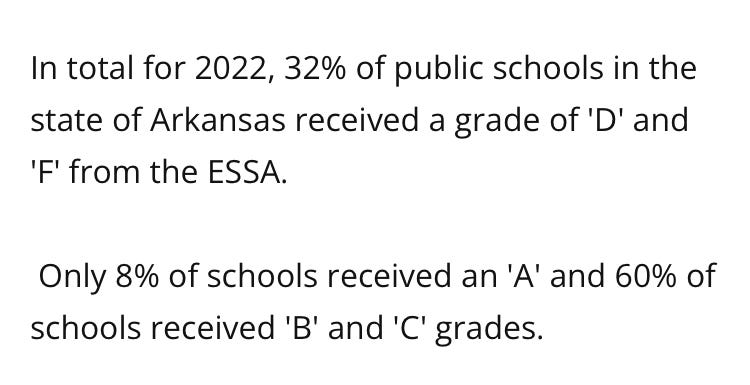

Local school funding is tricky business with a long history of legal battles, and I’m no expert. From ground zero long ago, however, tension between local control of public schools and inequitable sources of school funding has bedeviled educators. Arkansas attended to the issue legislatively near the beginning of the 20th century. Witness the following excerpt from a document reporting on public education in the Ozarks from 1920-1940:

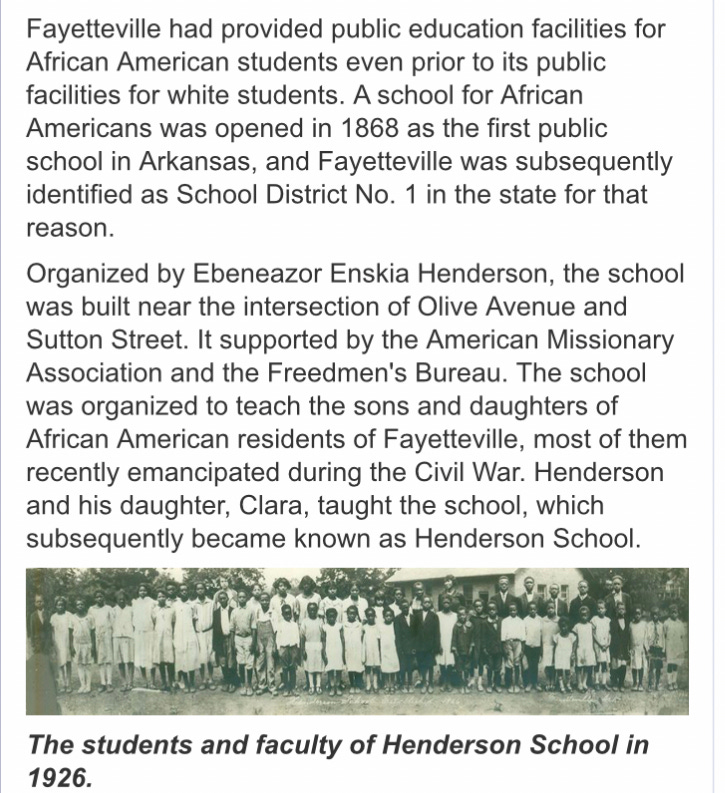

The quest for equity in opportunity to learn in Arkansas, if not equity in funding, reached a milestone much earlier in 1868 when the first ever tax-payer supported public school in the state opened. Reconstruction in the South, as W.E.B. du Bois testified, marked the birth of public schools for all of us in America, evidence that Reconstruction did not fail but was and continues to be suppressed, and one of the schools showed up in Fayetteville5:

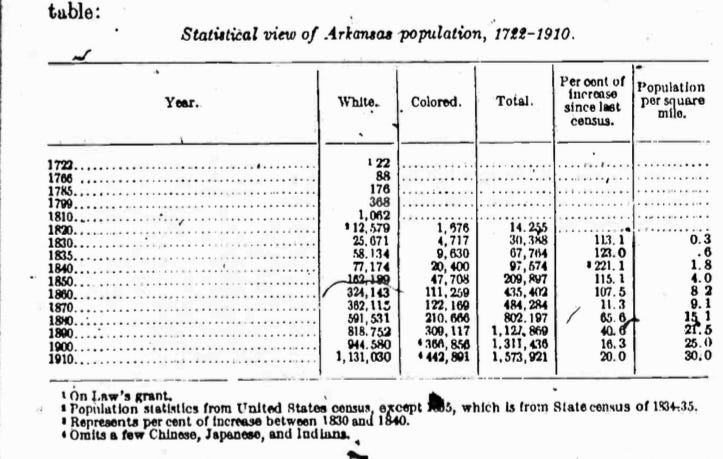

As the report of the Bureau of Education from 1912 cited below informs us, just under a third of the population of the state at the time was “colored” in the 1860s when Henderson School was opened:

***

Assuming that Arkansas is equitably distributing school funding as well or better than most other states, and given its history as a state government intending to bring the right to an education to all of its citizens, including all colors of people, what explains the ESSA finding that just 8% of its schools earn an “A” while 32% earn a “D” or “F”? One might conclude that throwing money at schools won’t solve the problem. Tanner (2018) sheds some light on this question available to all online, which I’ll discuss in the conclusion:

Since the 1960s when equity in school financing became a national concern after the Coleman (1966) report, California has also been at work on policy attempting to find ways to make sure that the right “dosage” of equity medicine actually has “exposure,” i.e., the money actually funds services for learners. Witness:

In contrast, Arkansas, under the leadership of Governor Huckabee Sanders, is busy crafting an Educational Freedom Voucher to coerce public schools, with legal mandates to serve all comers without charge while providing test score data for public accountability indexes like ESSA, to compete for funding with private or home schools, who have no responsibility for special education nor testing. In the meantime, according to USA Today, Sanders is also at work on multiple fronts to prohibit public schools from equitably serving its students without a thought about similarly prohibiting private schools:

Sanders has also taken a careful look at the role of bathrooms in education. As part of recent legislation criminalizing poor bathroom selection among transgender adults, in Arkansas it appears as if schools may be required to build single-occupancy bathrooms, though the bill includes no funding. One wonders how such funds might factor into the state’s equitable funding ranking.

***

Tanner (2018)6 reported important evidence that California is on the right track. Since Serrano the state has evolved from financing schools at a distance from Sacramento to sharing the responsibility for resource decision-making with educators closer to the local context:

The money was finding its way to the right places:

Importantly, Tanner (2018) found evidence of pay dirt:

**

So here’s my question to you: What sort of national and/or federal entities might be positioned to take the lead in provoking Governor Huckabee and her like-minded counterparts to attend to the politics of bathroom etiquette if they must and simultaneously attend to what really matters in the lives of the children in their states?

https://scholarship.law.upenn.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5262&context=penn_law_review

https://katv.com/amp/news/local/arkansas-schools-see-lower-grades-on-report-johnny-key-secretary-of-education-deborah-coffman-deb-jessica-saum-teacher-of-the-year-administration-f-failing-grades-c-a-b-every-student-succeeds-britney-hickman-sylvan-hills-elementary-

https://arkansasadvocate.com/2023/02/13/rural-districts-concerned-about-voucher-program-accountability-school-closures/

https://wallethub.com/edu/e/states-equitable-school-districts/76723

https://www.fayettevillehistory.org/education/

https://gsppi.berkeley.edu/~ruckerj/Johnson_Tanner_LCFFpaper.pdf