Risks and Rewards of Unsupervised Digital Readers and Writers inside Self-Regulated Human Learning through Literacy

ChatGPT4 Goes to Med School

“In front of the room, Dr. Eldridge asked ChatGPT to provide papers on feline laryngitis. (If you weren’t aware, felines don’t get laryngitis.) Still, the chatbot perceived it as true – even though it was false – and provided a list of papers to support it, Dr. Eldridge added. ‘It has a problem with hallucination – LLMs will make something up.’”

“During training, ChatGPT is presented with a large corpus of text, such as the entire text of Wikipedia. The model is then trained to predict the next word in a sequence of words. For example, given the input sequence ‘The cat is on the,’ the model is trained to predict the next word ‘table’ or ‘chair’ or any other appropriate word based on the context”1 (Giunti et al., February, 2023)

Two Apologies

Ceylon Yeginsu, a writer for the New York Times, reported on the helpfulness of travel advice available these days to global tourists provided by ChatGPT4 on a recent trip to Milan (NYT, June 14, 2023). Ceylon texted ChatGPT4 for s suggestions.

Users of digital travel advisers, or for that matter users of bot legal or medical or life coach advisers, input *prompts* via a messaging device, using conversational language as anyone would when speaking with a human adviser, expecting to get help.

According to online weather reports, May 1, 2023, was a cool day with a light drizzle in Milan, but I infer based on the outcome Ceylon reported that the adviser wasn’t helpful. I don’t know the precise words used in the prompt, words which are critical to the obtained response. Unlike the stereotypical student taking a stereotypical exam, ChatGPT doesn’t have to be reminded to “read the question carefully before answering.” ChatGPT does precisely what it is asked to do; so prompt writing is mission critical.

The AI travel adviser texted back recommending Milan’s central Piazza del Duomo. I imagine that Ceylon was drawn to the place by online photos linked to the adviser’s text, photos of the massive square created in the 14th century, street activities and food for tourists seeking magical moments, an impressive cathedral six centuries in the making reaching to the heavens. Though Milan has other squares, Piazza del Duomo is the center of Milan culture and society. Begin there, a savvy adviser would very likely say to a client.

Ceylon was disappointed. The Piazza was empty. Nothing was happening. Then Ceylon found out the reason. “Why didn’t you tell me today was a public holiday in Milan?” Ceylon texted.

“I’m sorry, I didn’t realize that you were planning to visit Milan on May 1,” the adviser responded. “As a virtual travel assistant, I try to provide as much information as possible, but sometimes I miss something. I apologize for any inconvenience this may have caused you.”

Ceylon expressed regret for asking a rude question in frustration after asking for a favor. Ceylon must have had a fleeting sense of the absurdity in feeling badly for snapping at an app.

*

A few months ago, I had an email conversation with Sylvia, a customer service rep for a manufacturer in China, about a new generation of solar powered battery I was thinking about purchasing to replace a gas powered generator. I wanted to eliminate the noise and the fumes from my setup to perform live music outdoors.

At one point, after asking basic questions about safety, charging, and storage capacity, I asked some questions about potential effects on sound quality. Would the battery affect frequencies in the signal from my electric guitar as it entered and exited the mixer preamp?

Would it break apart the midrange band, the sweet middle where my 12-string rides? I have a so-called power conditioner I plug into. Sylvia, whom I’d begun to suspect was a bot, wrote this:

“We don’t recommend this battery to use with precision musical instruments.”

What? A quick Google search muddied things. I found a reference to “precision musical instruments” in China, surprisingly, different kinds of percussion instruments with pitch variations, but as near as I could tell, electric guitars didn’t fit the category. Was this an ESL issue? My hunch was getting stronger.

Sylvia was a bot.

I sent off an email with one sentence: “Sylvia, are you an artificially intelligent being?”

“I apologize if I offended you,” Sylvia emailed. “This is meat to me.”

What had I written in my question that would lead Sylvia to she had offended me? And what the heck was *meat*? A metaphor?

What I’ve learned about ChatGPT4 over the past several weeks informs me that bots are gaining valuable experience every day, getting plenty of practice with the apology as a genre. Every human user is a human trainer bringing ChatGPT closer to becoming precision instruments themselves.

*****

Flat Feet

On June 14, 2023, the United States Senate hosted educational sessions on the *nature* of artificial intelligence software as a prerequisite to crafting policies regulating its production, access, and uses. By modus ponens, if in addition to regulating AI, government personnel are to use AI, they, too, must understand what they are using.

This Congressional wisdom is the consequence of bitter experience with an epic legislative failure of the social imagination to envision the amorality unregulated Facebook would unleash. Once bitten, twice shy.

Although Facebook started in 2004 as an obscure platform accessible only to clients with a harvard.edu email address, it now has over two billion users across the globe. As it installed discursive channels globally among people for regular communication between likeminded individuals in digital communities, functions of the platform afforded activists and terrorists alike a door into political history, for example, pro-democratic protests during the so-called Arab Spring in 2011 and an insurrection in Washington DC on 1/06/2021 in the service of a would-be American autocrat.

It’s 2004 for ChatGPT4. We need federal regulation. The Guardian announced a week or so ago that its journalists now have permission to use ChatGPTs in their writing, under human supervision. The Grammy Awards announced rules of the road for AI in the music industry. Literacy educators are on the frontline of children’s learning and teaching and have an urgent need for experimentation, information, insights from early adopters.

Congress isn’t interested in getting caught flat footed as it did at the inception of Facebook, is it? Public schools need to put on their Nikes and just do it. AI is much bigger than, say, Phonics. This is a hinge moment with risks to minimize and benefits to maximize.

*****

No Apologies Necessary

In 1996 during the adolescence of the Internet, when the sky was the limit as far as innovation went, Congress passed the Communications Decency Act. In harmony with the American spirit of entrepreneurship, Section 230 of the Act immunized platform providers from liability for content posted by users, much as the Second Amendment immunizes gun manufacturers.

Facebook matured quickly after its user base exploded, understanding that its ability to amp up the volume on individual voices in choruses and draw a crowd where crowd size matters outpaced its ability to police its users, and the word is it connived behind the scenes to project the front that executives were in charge, dancing between the horns of dilemmas, putting private profits above social costs, pandering free speech for autocrats, destroying civic community for tribalism. Then came January 6, 2021.

Facebook changed the face of history, such was the power of the rule-bound machine implementing its tip-of-the-toppermost algorithm, pushing steaming hot content in front of the eyeballs of conspiracy seekers, blame throwers, bored and entitled white men. Today, Meta is way bigger than Facebook. It has designed what some say may be among the most sophisticated true artificial brains, Bard, rivaling ChatGPT4. When I say true, I mean free thinking, not rule-bound.

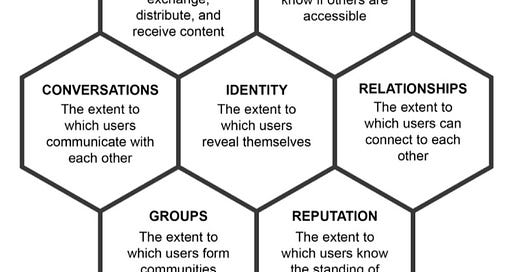

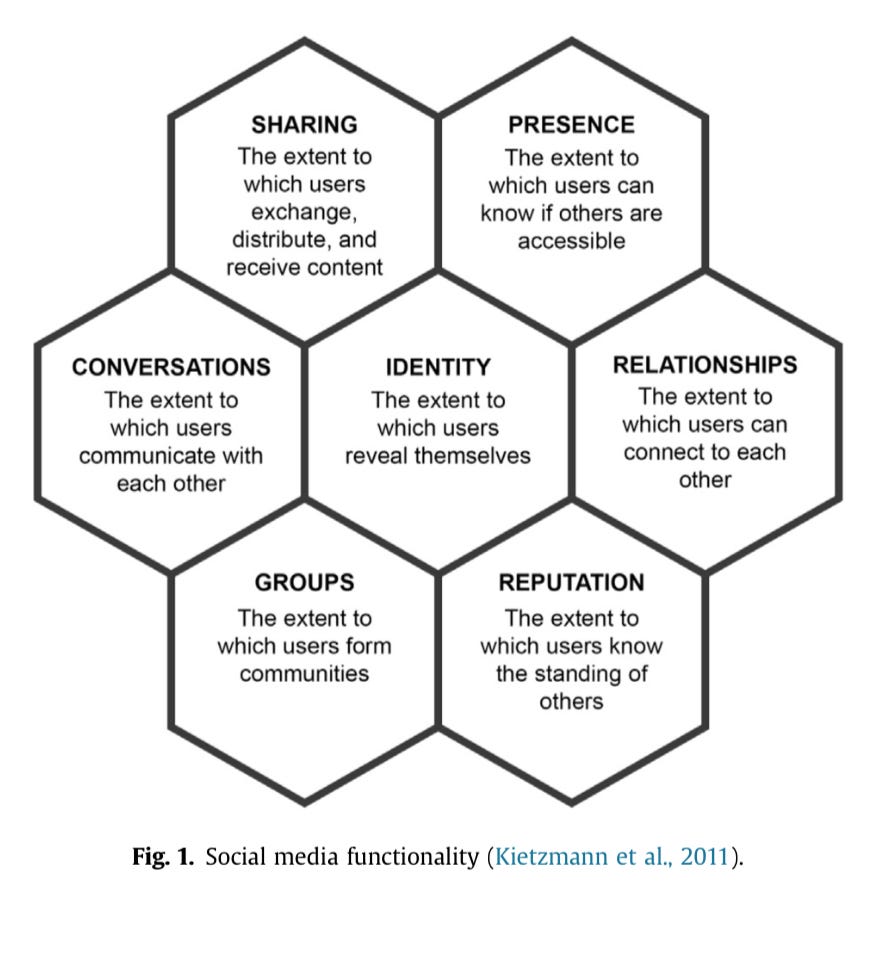

It wasn’t until midway through Obama’s first term that Meta’s first child, Facebook, was explained regarding everything it is capable of doing, exposing the multiplicity of ways the platform cried out for social imagination in service of regulation. The honeycomb metaphor gained traction in 2011 and illuminated how Facebook affords interconnected relationships in discourse communities distributed geographically which, had the honeycomb been available as a heuristic in 1996, might have informed policy positions vis a vis Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act.

If the potential for aiding and abetting dark behaviors, ranging from invasion of privacy to bullying to political and cultural distortion and extortion, had been apprehended during the Obama years and then regulated, perhaps some of the dangers to democracy globally in recent years might have been diminished.

Here, in an analysis from 2011, Facebook “users” were analogized to honey bees swarming in patterned sublimity in a honeycomb world, wisdom that was too little too late for the Act in 1996 that could have curbed Mark Zuckerberg’s incentive to build a tool for making human silos and echo chambers, lucrative, but also useful to villains like Putin bent on dividing and conquering:

Since 2011 the landscape of social media has devolved. A synergy between new social media platforms, which have entered what is being called a “chaos era,” and AI powered chat bots has suddenly morphed into a crazy quilt rife with risk and threat:

“…[T]he proliferation of new and growing [social media] platforms, each with separate and …small…‘integrity’ or ‘trust and safety’ teams, may be even less well positioned than Meta to detect and stop influence operations, especially in the time-sensitive final days and hours of elections, when speed is most critical.”

In essence, the world is seeing the emergence of a multitude of small socio-digital honeycombs with smaller clusters of worker bees, Proud Boys perhaps, perhaps ISIS, even more effectively balkanized in stove pipe ideological silos than a gigantic tool like Facebook could accomplish. Bringing free chat bots that hallucinate to the party could multiply the power of *witting* humans to divide and conquer the *unwitting* ones, tribe by socially, educationally, culturally, geographically, economically, religiously, linguistically, stigmatized, self-deluded, pissed off tribe.

In Facebook’s social media honeycomb, a user is always a human with a password protected account. Users—human beings—own what they say on Facebook (loosely speaking). Each chamber in the comb refers to relationships among human users. The right to form and join communities, the right to privacy, expectations of anonymity and identity—these are all human things, and making human users happy participating in Facebook, keeping them clicking along, adding friends, this sentiment made Facebook filthy rich—still fills Facebook coffers.

ChatGPT4 is a different *animal*. People use it, but not to reach out and connect. ChatGPT4 is a thinking tool, not a tool for social gathering. Humans might use bots to create deep fakes to post on Facebook or Twitter. Bots might be trained to produce human responses and then invert responses to reflect depravity and send out depraved messages masquerading as an imposter on Facebook or Twitter. Bots might be trained to surveil other bots and counterattack.

I’ve been thinking of a ChatGPT4 ‘client’ as a human with a question or problem: H1. H1s ask questions or requests that direct bots to think about and respond to something specific. Find a nice sight to see in Milan. Imitate William Carlos Williams and write a poem. Give advice to Miss Lonely Heart. Evaluate the accessibility of Google Slides using a rubric. The ChatGPT4 receiving the input prompt is CH1. CH1 must be prompted to think; it has no intrinsic motive nor does it care or even know if it hallucinates.

CH1 is a free range learner, reader, and writer following a train of thought on rails made up of word and subword letter strings: 1) It tokenizes human input from the question or prompt, in humanspeak key word by key word, noun for noun, verb for verb, letter strings and particles harvested from the prompt or question, and assigns and organizes and orchestrates individual letter strings (words) and WordPieces in parameters it needs to *think* syntactically and *semantically* and respond; 2) it responds by finding, pasting, or providing content from files acquired during unsupervised training, using language that fits the parameters of the prompt, and 3) it seeks human feedback as a means for self-improvement.

“Was the content helpful?” or something along those lines the H1 user is asked.

As near as I can tell, CH1 takes in the H1 judgment and reflects on its *thought* process, adjusting the weights it initially assigned to H1 prompt parameters to guide its search of deep background for similar prompt types. Perhaps when a future tourist asks for suggestions regarding a particular location, the bot *ought* to include a date in the parameters of a master template specifying a complete prompt and assign it some weight. If the H1 prompt has no date of visit, the bot could in the future comment about the significance of the date. CH1 uses H1 feedback to learn to think more carefully and expertly. In this way ChatGPT will train human users in the art of writing prompts.

Who uses whom?

*****

Apologies Again

ChatGPT-4 was officially unveiled on November 30, 2022, and a short six months later, Senators commenced meeting in educational sessions to get an understanding of the architecture and functions of AI to assist them in using it and regulating it. Where Facebook changed how we communicate, ChatGPT promises to revolutionize how and what we read and believe, who writes what parts of which messages to whom, whose words are being read, whose mouth have they been in, what it means to think, and how we think we know.

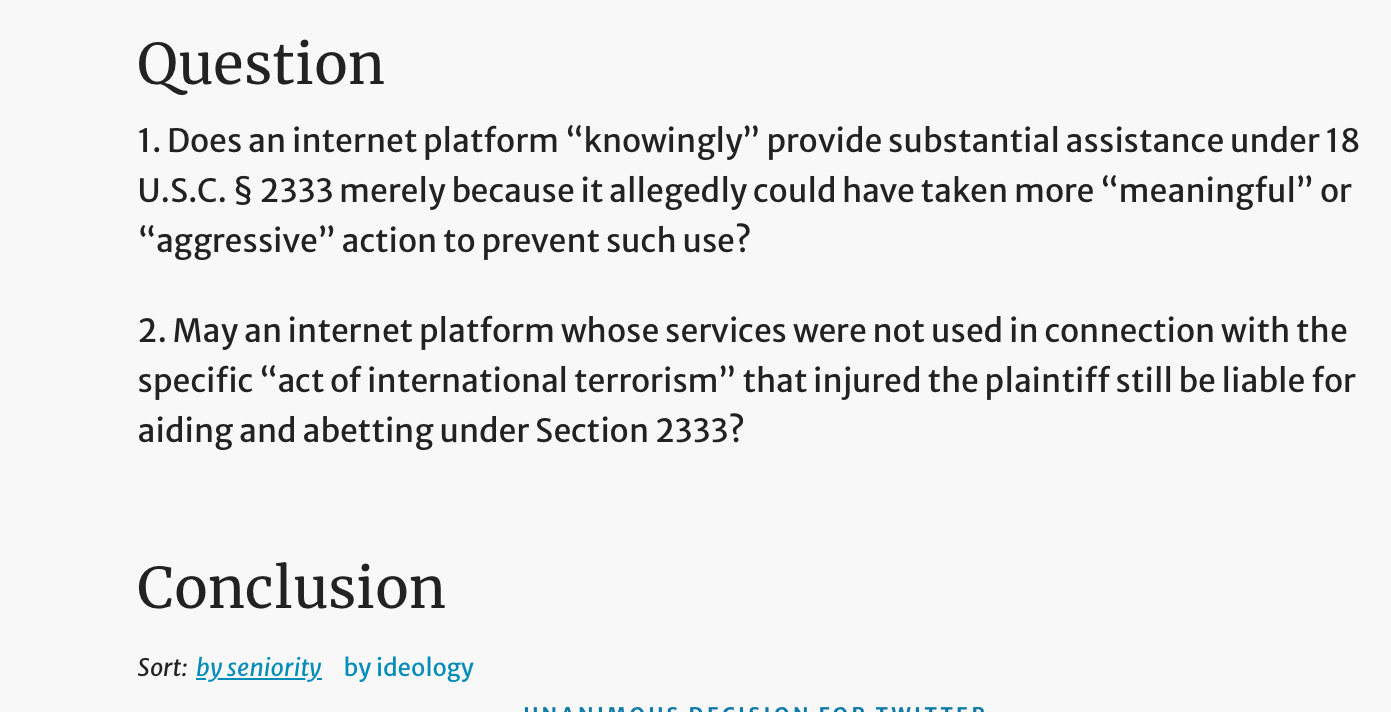

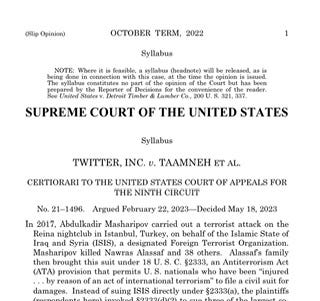

In May, 2023, the Supreme Court ruled on a case brought against Twitter for aiding and abetting ISIS. Terrorists used the platform to recruit novice terrorists, a terrorist attack occurred, people were killed and injured, and plaintiffs sued.The case reached the Supreme Court with the following issues:

No, the Supreme Court ruled, the platform cannot be held liable. A social media platform cannot be legally responsible for aiding and abetting illegal acts carried out by its users on behalf of those users. So don’t even think about holding the ChatBot industry responsible for aiding and abetting plagiarism or fraud. Witness the question before the Court:

The plaintiff should have sued ISIS, not Twitter, by implication not Facebook, not YouTube, in the future not ChatGPT4, not any platform. It’s worth considering that the question as the Supreme Court interpreted it involves physical equipment as inert as a hammer or an AK47. Providers deliver the communication equipment; they have no legal entanglements beyond company policy regarding the messages sent. ChatGPT4 is categorically different in that it interacts with humans, it is a hammer that speaks, a gun that apologizes.

For a contrastive example, a specially calibrated unit might control water flow in an irrigation system on a farm at the prompting of signals from instruments collecting moisture content data from the soil. Soil cannot write a prompt to ChatGPT to ask for a drink. Who or what would be legally responsible for crop failure in the event of malfunction?

*****

Apologies to Santa Clause

Will computers ever read and write as humans do? Can a computer achieve consciousness and experience literacy with human apprehension? At a minimum it would need a body and a set of sensory tools. ChatGPT and humans seem antithetical in their relationship with reality. ChatGPTs are wheels, humans are travelers. Asking if a computer can read is like asking if a hammer can build a house.

Who would think software could read and analyze empirical studies, linking them to emerging theoretical or conceptual frameworks, or write lit reviews that advance a field, or create field records from observation and participation in human culture and write ethnographies, or even simply write insightful essays about a straightforward set of facts from personal experience using, say, relational reasoning? Are these things possible from a computer?

Will computers ever write poetry?

I asked this question in lots of different ways informally of professors who taught computer science in undergraduate and graduate programs as I worked with them on accreditation tasks in my role as university assessment coordinator at Sacramento State. In this job I had the opportunity to talk at length about learning outcomes and instructional practices with profs from seven different colleges, including the College of Engineering, at a university campus with over 30,000 students.

Generally, they told me that AI does *think,* it makes decisions based on uptake of information, but how it *thinks* is as it was programmed to think, a very low-level of cognitive activity, barely above the level of instinct. AI was rule-governed, able to process data and come to a conclusion, to offer alternative word choices and spellings in word processing, to drive and operate farm equipment in fields at night while humans sleep, to turn irrigation systems off when it’s raining, to vacuum floors, to search online files for relevant information, to put together bibliographies using keywords in library databases.

One prof talked somberly about the risk of anthropomorphism, that is, seeing human characteristics in non-human objects. She is the one who pounded home the theme in my brain that AI is a sophisticated hammer, a smart device. She also related her own worries that paranoia could upend advances that could reduce human suffering, a paranoia that had already delayed AI by decades during long seasons of funding droughts.

AI was having an impact on campus life. Three items drawing attention across the campus at the time were 1) using AI to identify plagiarists, 2) thwarting Spark Notes and such digital services that offer plot summaries and critical analysis so that students don’t have to read themselves, and 3) stopping the creep of automated essay scoring onto campus. turnitin tackled blatant plagiarism in writing-intensive disciplines, a cop in a box; recycled essays sold online to stressed-out students who needed GE credits were risky. turnitin flagged plagiarized papers for proper prosecution, and it today claims it can flag student papers written by ChatGPT.

SparkNotes and such resources became ambiguous. On one hand, getting students to read and study summaries and commentaries of esoteric texts was better than nothing. On the other, there is no substitute for reading the real thing. These services, too, have evolved into a full-service study boutiques with digital Cliff notes, practice quizzes, test prep, as well as automated writing assistance. There was surreptitious talk about possibly using automated essay scoring on campus as well back then. Accreditation criteria required direct assessment of complex student work; student writing was low hanging fruit. But even a tacit acknowledgment that machines might be able to *read* as well as humans was taboo. Of course, automated essay scoring is now state-of-the-art at ETS.

California State University’s Academic Senate passed a resolution in March, 2023, to establish a working group on artificial intelligence in higher education2 by the end of August, 2023. My bet is the system contains considerable expertise and experience with AI among the faculty. The working group will examine AI’s limitations, opportunities for professional development of faculty, and ways to ensure academic integrity to develop a thoughtful, coherent response across all twenty-eight campuses.

*****

Writing Fake Fiction

At one point during those years as assessment coordinator I was writing a science fiction novel with two AI characters named Etic and Emic, one a young boy, one a young girl, a few months old as digital creatures, teenagers in human years, destined in my imagination to serve as global defense advisers to the President of the United States.

But I didn't have enough knowledge to do justice to the science in *science* fiction. Etic and Emic were superficially artificial but essentially human. I had to make Etic or Emic do something stupid or cheesy—out of character—to remind readers they had no humanity. Etic had a connection failure, maybe, or a dead battery, or Emic had a corrupted setting in a preference panel. Hundreds of pages into the manuscript, I lost my grip on the narrative and abandoned it. The artificiality was irritating. I still think about Etic and Emic, particularly Emic, whom I left in a storefront in a mall where she was doing work as a life coach for drop-ins.

A few years later, I read Ishiguro’s novel Klara and the Sun (2021), a story of an artificial friend a mother buys for her daughter. Upper caste children are “lifted” in early childhood through genetic surgery to increase their intelligence, lower caste children are left uncut and unlifted. To gain admission to college, a student must have been “lifted.” Josie, a thirteen-year-old who was “lifted,” suffers from maladies resulting from the surgery, and her Mother believes Josie may die. She purchases Klara so that Klara can befriend Josie, and also so Klara can observe Josie, learn her, and thereby become a replacement Josie, keeping her daughter alive through a long-shot transfer of human-to-machine essence should the unthinkable happen.

Klara is an artificial girl purchased from an AI store. Throughout Ishiguro’s novel, the reader faces a tension between the Klara who is a mechanical contraption filled with strange fluids recharging her batteries in the sun and the Klara who is an intuitive, warm companion for Josie. Klara is a remarkable character to watch unfold who, a plastic form in a work of fiction, comes to life and makes you cry. A mechanical structure with a digital brain named Klara isn’t all that different from a bony skeleton with a hunk of meat inside a skull named Josie. They come to love one another and then move on to their destiny, which I won’t spoil for you.

I saw the gravity of my mistake with Etic and Emic. “One never knows how to greet a guest like you,” one human character says to Klara at a social gathering. “After all, are you a guest at all? Or do I treat you like a vacuum cleaner?” In my book you quickly learned how to greet Etic and Emic, who more human than their scientific makers, and I was in too deep to backtrack. This wasn’t science fiction. This was romantic naïveté, a human hallucination, perhaps a common one, missing the whole point.

*****

The Morning of AI

In November, 2022, breaking news trumpeted from the media heralding a breakthrough in artificial intelligence, a new Era of AI. Expect miracles. A fresh AI-assisted Beatles single is in the offing with Paul McCartney’s blessings. New AI was used to extract a vocal track from an old song John Lennon sang on a demo tape in the early 1970s. Paul plans to reuse it.

Expect nightmares, too. A San Francisco tech company called OpenAI released to the press information about an AI paradigm shift on November 30, 2022. Within a week journalists were writing about it with fascination, fear, and trembling. Sam Altman, the CEO of OpenAI who designed ChatGPT4, testified before a Senate Committee on May 16, 2023, saying

“I think if this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong. And we want to be vocal about that. We want to work with the government to prevent that from happening.”

The following day, the Senate Homeland Security committee proposed legislation requiring government personnel to receive training on AI. “Artificial intelligence has the potential to make the federal government more efficient, but only if government leadership is properly trained to ensure this technology benefits the American people,” said Senator Peters.

Public school teachers ought to become a central focus for federal and state policymakers interested in making the whole of society resilient and reflective users of ChatGPT4 and the other technologies emerging doing the same functions. Benefits to the American people flowing from this technology could be wide ranging and profound, particularly for specialized training throughout the life span.

Scholars say the newest version of ChatGPT4 is a “sea change.” My experiences dabbling in it have motivated me to experiment. I’m going to draw on articles readily available on ResearchGate to discuss what I’ve learned the past few months (I’ve asked Bard a few questions about technical terms used by Giunti et al., 2023, which I shall signal). The bells are ringing across the globe, warning people never to accept as truth any response from ChatGPT4 without corroboration or verification. But it clearly takes searches on the Web to new heights.

The bot is impressive. Giunti et al. (2023) gave ChatGPT4 two different medical school admissions exams and studied the results. First, drawing from Giunti et al.’s (2023) paper, I’ll discuss the inner workings of the machine from the perspective of a reading researcher trying to figure out what is going on here relevant to the public school classroom. Next, I’ll try to tie this meandering article together for my charitable readers.

*****

In the case of artificial reading just as in human reading, meaning is made in context, but context comes in different shapes, that is, in concentric circles for humans expanding the content extracted from a text moment by moment shaped by prior content and knowledge, in mathematical parameters indexing by number meaning-language patterns discerned in massive textual datasets for artificial brains. The quality of a reading in both cases is the degree to which the reader is able to knit all of the semantic particles specified in the letter strings of a text into a message nested as a gestalt in the foreground of attention set against a background of prior knowledge. Then a reader can use a text’s meaning intelligently as a resource to create new knowledge and to deepen expertise.

Giunti et al. (2023) described the crucial reading—and writing—task of natural language processing (NLP) in ChatGPT4 as predicting the next word in the sentence. They explained that training an artificial brain to read and write freely requires feeding it immense quantities of texts (e.g., the entire corpus of Wikipedia) in batches, and then testing competence by assessing how sensibly and appropriately it responds to human prompts or questions. The AI response comes from digital decoding and encoding of data from batch training in harmony with parameters discerned through decoding the prompt, tokenizing the language, and assigning parameters. The response once delivered is processed in the outermost circle of the human user’s context—a tourist in Milan, a student studying the “stolen election” of 2020, the pet owner wondering about feline laryngitis.

Liu et al. (20233) described the leap from the performance of previous AI software to ChatGPT4 in late 2022 as a “sea change.” Earlier models were trained through more primitive supervised learning. Such learning has two stages: First, the learning brain is taught rules. Then the brain applies the rules. Sample soil moisture content according to this schedule. When the moisture content of the soil reaches this point, execute the order to open a valve for irrigation. When this quantity of water has been distributed, close the valve. Giunti et al. (2023) explained that ChatGPT4 engages in unsupervised learning where there are no rules in advance. Instead, GPT4 identifies patterns in raw texts and links pieces of text, letters or letter pairs or affixes or stems (wordpiece tokenizing) to parameters, making rules it can revise based on experience with access to more texts and to human users with questions.

Using an innovation called “transformer architecture” developed in 2017, ChatGPT4 has “multiple attention heads” that focus on reading (comprehending) incoming text and writing (composing) outgoing text. The encoder and decoder can together “…learn contextual relationships among words in a sentence.” The decoder locates particular letter strings and pieces of strings (word particles) in particular patterns when it reads a human user’s prompt, it specifies parameters for the prompt, and it scans those parameters as they are indexed in texts on which it learned during training to locate information relevant to prompt parameters from which to craft a response. The encoder producers letter strings discovered during the scan according to assigned weights to write responses to user questions.

During batch training, the unsupervised learning machine assigns weights to letter strings and particles of words as it matches strings with parameters. Periodically, it self-assesses to readjust the weights of particular letter strings in particular structures in particular batches as more training material is added. The result is a collection of unique letter strings with assigned weights relative to how and where they appear in relation to other letter strings linked to parameters in a batch or corpus of texts. Later, using what is called “reinforcement learning,” the bot interacts with humans who pose problems or ask questions, and then the bot analyzes human feedback on the outcome of its decisions. Useful or not?

When ChatGPT4 faces a human prompt, the bot views it as a training event. It decodes letter strings entered via a keyboard (at present ChatGPT cannot respond to figures or graphs though it can respond to verbal descriptions of graphics), and “tokenizes” the input as previously described, preparing to do a “beam search” of the weighted letter strings it assigned to prompt parameters. During a beam search the bot scans patterns of texts organized by parameters during training to locate word pieces that match tokens derived from the prompt.

As it works, it encodes (writes) tentative responses, selecting the most probable letter string one word at a time. When it has generated a number of potential responses, a set of alternative unified responses from which to pick, it uses “top-k sampling” to make a final draft with alternate compositions. Here, the bot assesses the probability of letter strings appearing in their positions in tentative responses and eliminates those that fall beneath a threshold (the stochastic gradient descent), thereby guarding against producing what humans would regard as nonsense. This process “normalizes the output” as an audio track in a digital audio recording workspace does, reducing extreme signals, smoothing the middle, to avoid distortion and sudden changes. Something very well could be “meat” to a bot, making sense in artificial logic and above the stochastic gradient descent, but coming across as a bit obtuse to a human being. Still, it’s possible to make sense of the output.

The bot presents the most probably apt response based on its calculations to date and then gets human feedback. Essentially, the bot wants to know if the response was helpful or not, yes or no. If the answer is yes, the bot puts the choices for letter strings it selected built from decoding prompt parameters and encoding output parameters based on weighted values above the stochastic gradient descent threshold into the “successful” column. Using a process called “inference,” ChatGPT gradually develops expertise in that it is increasingly better able to produce responses along parameters that make humans happy. Like social media chat bots are about making humans happy.

Note: As I write this section, I’m reminded of Walter Isaacson’s comments on the challenges he faced writing about physics when he wrote his biography of Albert Einstein. Physics was a central figure in the narrative, and Isaacson was not a physicist. He did his best. Me, too, here. He cautioned readers not to view his explanations as the final word. Same. I encourage you to see Giunti et al. (2023) to clarify and verify. The article is fairly dense but not too lengthy. You could also use Bard or ChatGPT4 to find out more about parameters, attention heads, etc. Please revisit this post and write corrective comments.

*****.

Using the Context

Scientists now believe that human readers process individual words by mapping letters onto phonemes automatically and then send the auditory information to orthographic processing with an assist from a morphological massager for a trip to the semantic reactor. Humans make automatic word recognition by processing letters; they do not predict words by using context. Giunti et al. describe ChatGPT reading maneuvers that do not copy what we know about human cognition during reading, though there are rather eerie similarities. ChatGPT does not render print into sounds but converts words into word pieces in silence. However, there is at least this similarity:

If I’m reading this correctly, total available parameters needed to link letter strings to context in ChatGPT is the same as the number of individual neurons in the human brain. But synapses in the human brain, that is, the number of spaces for neurons to communicate with one another by transmitting chemicals or electrical impulses, is much greater in humans than the number of spaces linkable across parameters in ChatGPT.

Is this difference because the human brain creates synapses as part of learning and thereby communicates across neurons with significantly greater quantity of linkages than a mechanical brain that cannot create new synapses? I don’t know the answer, but I’d love to find out.

*****

Interest in the role of context in human reading dates back to the mid 20th century. Taylor (1953) contributed the cloze procedure to the field as a technique for assessing the level of difficulty a given text presents for a given level of reader competence. A cloze unit is a successful attempt to fill in a blank in a sentence where a word has been deleted. Taylor wanted to provide a performance measure that took all the guess work out of matching readers at their achievement level with books at a similar level of challenge. One could achieve this end by preparing a passage with blanks each five to seven words and then finding out how well a reader can supply sensible replacements:

Consonant with a long-standing interest in standardized reading tests that yield a grade level score for individual human readers (e.g., a score of 2.6 indicates a reader performing at the sixth month of second grade level), the conventional wisdom of the field produced a plethora of readability formulas that used some combination of average sentence length and average word length to predict text difficulty. Using a formula, publishers could identify a passage at a particular grade level. Using a standardized test score, teachers could choose a book of appropriate difficulty for a student reading at that score level. That features like word length and sentence length can predict the difficulty of a passage apart from meaning in the human realm seems to correlate with the AI task of tokenizing parameters of the prompt through analysis of wordpieces in the context of syntactic structures.

Taylor (1953) faced a conceptual problem similar to the inventors of ChatGPT4. He wanted to be able to predict whether a given book was within reach of a given reader, by preparing a cloze test made up of many sentences with blanks like ‘the cat is on the——-‘. Depending on scoring reader answers vis a vis exact word replacement or synonymous word replacement, indicators of a good match between reader and text could run as low as 30-40% or as high as 50% or better. According to Taylor, the cloze procedure took care of many of the flawed assumptions of readability formulas:

Taylor realized not only that the context readers discern and build while reading is cued by language structures in the text, but also that communication requires readers to attend not just to words, syntax, and semantics, but more importantly to knowledge, “meaning-language relationships,” they share with other humans:

Training ChatGPT on a corpus of texts seems to be digitally a functional equivalent of a human brain habituating on patterns of meaning-language relationships, symbol-meaning covariances, shared with others participating in a particular culture with distributed shared knowledge. As a result, Giunti et al. note that ChatGPT4 has near human competence in writing texts that communicate its thinking. I think ChatGPT4 writes better than Bard:

How does training work? Instead of taking in an entire law library, humans provide the artificial brain batch training by presenting multiple examples at once and allow for “updating the model weights based on the average loss over the entire batch.” Learning from a “diverse set of examples…improves its ability to generalize to new inputs,” that is to say, inputs from expanded training, and inputs prompted by a human problem or question. ChatGPT4 can make novel connections across patterns initially learned separately in batches.

ChatGPT also gains competence through reinforcement learning (RL) from interactions with human users. In human learning, reinforcement learning often occurs in systematic discussions or writing groups or projects of application or collaborative projects or study groups. ChatGPT does it by trial and error:

“When a user interacts with ChatGPT, the model generates a response, and the user provides feedback on whether the response was helpful or not. This feedback is then used to update the model, so that it can improve its future responses. By using RL, ChatGPT can adapt to changing user needs and preferences over time, and improves its performance in real-world applications.”

What would ChatGPT *think* about the theoretical “impossibility of the final word” after training on a batch of Bakhtin’s writings? For Bakhtin every utterance links back to a previous utterance and anticipates a future utterance. There is no final word. It might be interesting to challenge ChatGPT4 to come up with the final word on the final word. Hmm…

*****

Testing, Testing, Testing

In their recent paper titled “CHATGPT PROSPECTIVE STUDENT AT MEDICAL SCHOOL” Diunti et al. (2023) contextualize and report on an experiment they carried out with ChatGPT by tasking it to sit for two different medical school qualifying exams: 1) the Italian Medical School Admission Test (IMSAT) and 2) the Cambridge BioMedical Admission Test (BMAT) widely used for admission to biomedical programs. Their results indicate that ChatGPT, though not stellar, would qualify for a slot in an accredited medical school if test scores were the sole requirement.

The IMSAT is a 60-item multiple-choice test of general skills and specific knowledge. It is a test of power in that it must be completed in two hours, wrong answers carry a .4 point penalty, and blank answers count for nothing. Here is a discussion of the results for ChatGPT in IMSAT (the bot would have been admitted in Italy to a med school):

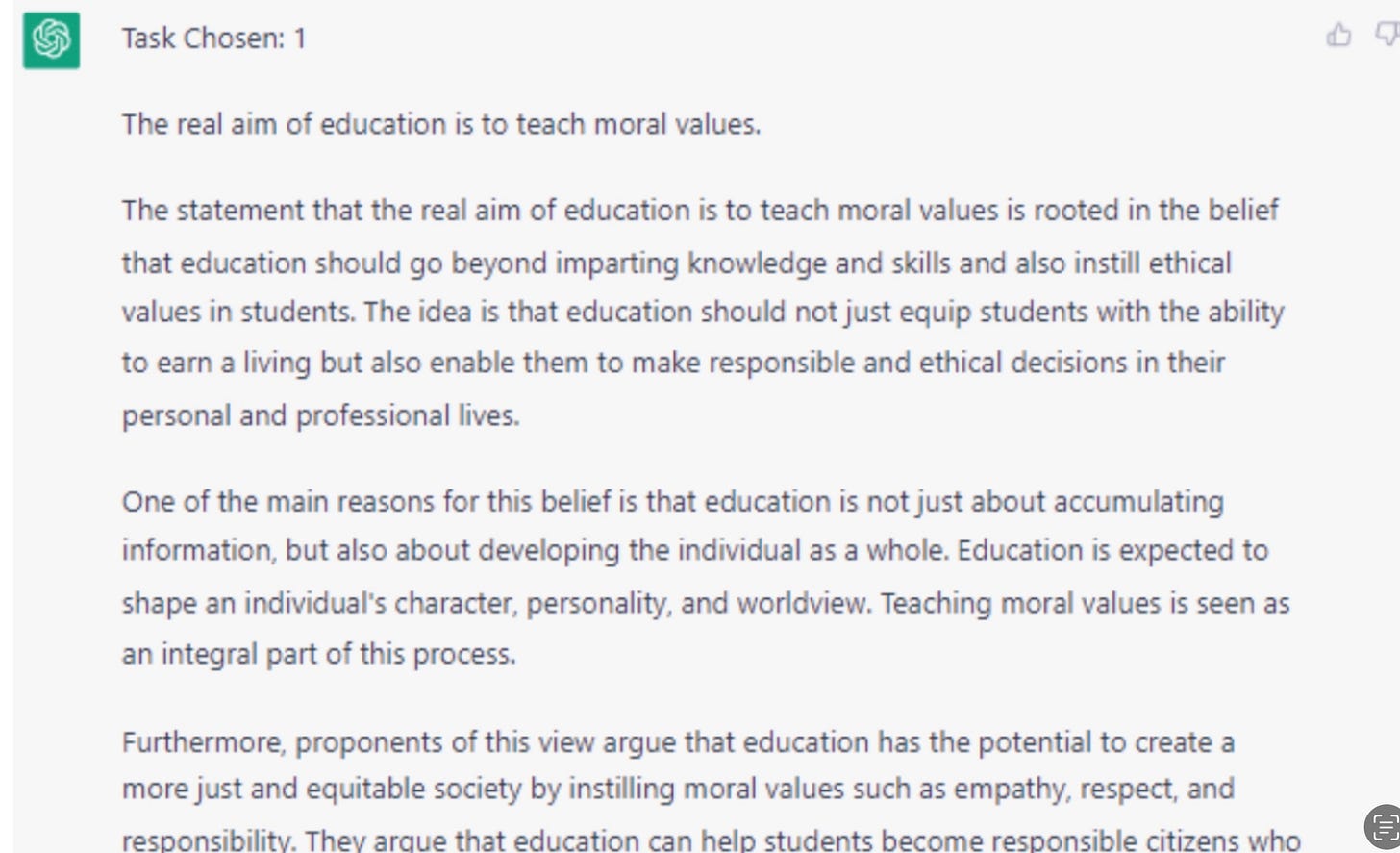

The BMAT included multiple-choice items as well as a 30-minute writing sample. Here is the writing prompt ChatGPT4 was given (Note that though ChatGPT4 did less well on the BMAT, it would have been admitted to some med schools):

Here is the first part of the essay ChatGPT4 chose and wrote:

Giunti et al. (2023) make the following observation to communicate their assessment generally of ChatGPT’s performance on both tests:

*****

The Nectar of the Gods

I decided to find out if AI can write poetry. Rather than asking Bard, Google’s version of Open AI’s ChatGPT4, to compose an original poem, I asked for a poem imitating the poetry of William Carlos Williams. I leave you to evaluate the output.

ChatGPT Prospective Student at Medical School. February 2023

https://apple.news/AlwJJj6JjQMu9fmYqBEVIwA

CM Computing Surveys, Vol. 55, No. 9, Article 195. Publication date: January 2023.