The Science of Science

The word ‘science’ has existed for thousands of years, sprouting from the Proto-Indo-European (PIE) root ‘skei-,’ meaning “to cut.” Interestingly, ‘skei’ has an outlaw PIE cousin, a word coming to us from the Old English word ‘scitan’ and the Proto-Germanic ‘skit,’ a word we know in English as ‘shit.’ In the ball of symbolic roots of our ancestor language, modern science is foreshadowed as a way of digesting reality, cutting knowledge from nonsense, flushing illusions down the toilet.

Capital S Science as we know it today is a social method of building knowledge with deep connections to law by way of licensing and credentialing which exploded in the 19th century after a long period of struggle with capital R Religion when scientists were heretics. Secular universities became spaces for the emergence of disciplines, each with a defined focus, a set of essential topics and questions, groups of faculty, learned societies, recognized journals, and bona fide highly accomplished experts.

Research methods most useful in a field were invented and perfected in a disciplinary context of expert peer review. Articles published in peer reviewed journals became sites for ongoing conversations over years and years with researchers carefully citing one another, building explanatory theories with evidence and analysis accumulating to support, modify, or supplant even mature theories.

Research activity was divided into basic and applied studies—basic research is done to answer questions with little to no immediate practical significance while applied research focuses on studying productive ways to use a robust theory in action. Universities now house faculties in disciplines who do research on Science itself, e.g., the sociology of science, the philosophy of science.

Little s science is a different construct but no less important. Babies are in some sense scientists and learn to build reliable knowledge without course catalogs, thesis advisors, and peer reviewers. Still, infant methods of natural study depend on the genetic equipment of our senses. Over time, with experience, toddlers learn that day becomes night, leaves fall, dogs bark, ice melts. They know with certainty it is raining when they feel raindrops on their skin. The rain is a truth maker with no need of a footnote or bibliographic entry.

Knowing that it is going to rain ups the ante for toddler scientists, getting even more difficult if the question is when the rain is going to stop. Such questions call on theoretical knowledge and statistical modeling—evidence-based explanations that are likely but not guaranteed. Dark clouds forming in the sky with wind blowing may be enough to support a conclusion that the picnic should be brought inside. But deciding on scrapping the launch of a space vessel from a NASA launchpad requires expert theory developed systematically and collaboratively—the hallmark of Science.

Science is not the only approach to knowledge production. Knowing that an event truly happened beyond a reasonable doubt can require considerable principled investigation in the wild, often based on a hunch. In a legal context establishing facts is central to drawing a justified conclusion of guilt or innocence.

The lawyer’s phrase “the facts of the case will show that…” entails first establishing these facts with testimony and evidence from people who saw or heard things. Interestingly, lawyers can introduce evidence from experts who saw nothing at all if the expert has sufficient qualifying training and/or experience. From the facts lawyers build a “theory of the case” or an explanation of what must have happened given these facts.

The process of knowing in a courtroom is rule-governed and formal with built in appeal systems. Lawyers behave unethically and illegally if they willfully distort or misrepresent any fact to support a bogus theory. Legally valid knowledge is carefully made and presented in court according to rules of evidence, fairness, and established practices that unfold with a disinterested third party or an unbiased jury of one’s peers reaching a conclusion.

The types of questions scientists ask flow from a broader academic search in which other scientists past and present participate. Researchers interested in earning doctoral degrees must first qualify for the right to frame a question by proving to a committee that they have mastered a rich enough body of knowledge to enable them to interpret their findings and connect them to a theoretical framework.

Reading scientists develop theories through basic and applied research and write papers to submit to journals where blind peer review protocols are used to evaluate whether a study contributes to the knowledge base under construction in the field. In more recent decades disciplines not centered on reading have produced scientists who ask questions about reading including psychology, anthropology, linguistics, sociology, and more.

Unlike, say, meteorologists, reading scientists do not study natural, physical phenomenon like weather. These scientists study an unnatural, cultural invention which is thoroughly human in origin, although biology plays an important part as it does in all things human. Quantitative methods and assumptions that work for meteorologists, however, can work for reading scientists when they ask basic questions, like ‘How many letters do readers perceive during a single eye fixation?’

Constructing a scientific understanding requires appropriate methods for collecting and analyzing data. A question like ‘Why is the reading achievement gap between children of color and affluent children in America so resistant to change?’ can be approached through both quantitative and qualitative methods. The Science of Reading uses an expansive toolbox to understand the reasons some children become competent, engaged readers while others do not.

As a way to illustrate the participatory foundation and critical evaluation of studies that make their way into the ongoing scientific conversation, I will discuss my own experience joining the Science of Reading community.

Using the Science of Reading to Learn about the Role of Motive and Motivation in Reading

The sky needs no motive to rain, but a reader must have a motive to exert sustained, persistent effort, especially when processing challenging texts requiring strategic cognitive moves with little access to help beyond the four corners of the text.

I wrote my doctoral dissertation in part to contribute to our shared knowledge base about the relationship between grading practices and motivation to read serious literature among low-socioeconomic, diverse middle school students in California.

More specifically, I wanted to document the effects of a local portfolio assessment system, designed to reshape and channel the power of the existing quiz, test, and grade culture, to increase students’ motives for exerting effort in their Language Arts classrooms.

At this middle school students received letter grades in a report card sent home to parents each trimester. Through agreements with the school principal and the English Department, I was able to conduct an experiment wherein grading practices were modified.

Traditional grading practices were in play at the school. Each individual teacher was obliged to apply a reasonable scheme, e.g., make assignments and grade them, give tests and score them, keep a grade book, and submit grade rosters to the school office. Although colleagues had a passing awareness of one another’s grading activities, for the most part they were solitary, idiosyncratic, and tacit.

Three English teachers agreed to teach for the year of the study and give up their authority to issue grades. Over the space of a trimester students were to negotiate learning goals for themselves with their teacher, self-select books to read, and self-select writing assignments. Their teachers worked with them to support their work with feedback and conferences and to directly teach reading and writing strategies in mini lessons.

Although there were no grades issued during the trimester, discussion of grading criteria on the rubric were plentiful. Near the end of each term, students were required to create a portfolio to submit to an external examination committee who used a jury method to achieve consensus on a letter grade for each portfolio. This grade was entered on the reporting document that went to the school office and went out on the report card.

Portfolios had defined compartments with student-written reflective analysis which were rated in their totality according to criteria spelled out on the portfolio rubric. Students had ready access to the rubric, and the teachers spent quality time discussing the criteria with them.

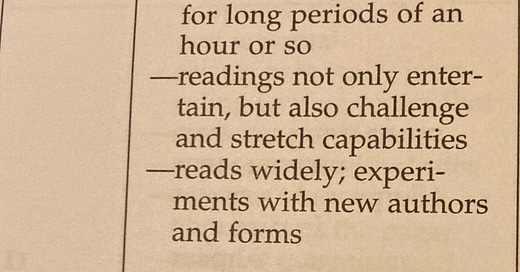

They came to understand what, for example, they would need to do to document their achievement in the area “consistency and challenge.” To score in the “A” range on this learning outcome for reading, the rubric specified the following standard:

To help them achieve this outcome, the portfolio teachers collaborated with the librarian to develop a field trip to the library wherein preselected books representing both fiction and nonfiction were stacked on tables by topic or genre. Students were taught a strategy for “sizing up a book” to decide whether it would be a candidate for a goal. They developed a list of ten titles and authors with appeal, brought their list back to class, and discussed their findings.

Once a book was listed as a goal, students were expected to read it. They could “abandon a book” if it didn’t pan out, but they had to write a reflective note explaining why. They also had to replace the title on their goal list.

The portfolio teachers emphasized that good readers were rarely “lost.” Indeed, good readers usually had books waiting in the wing. When the current book was finished, the next book was in line. They also learned that good readers often are reading more than one book.

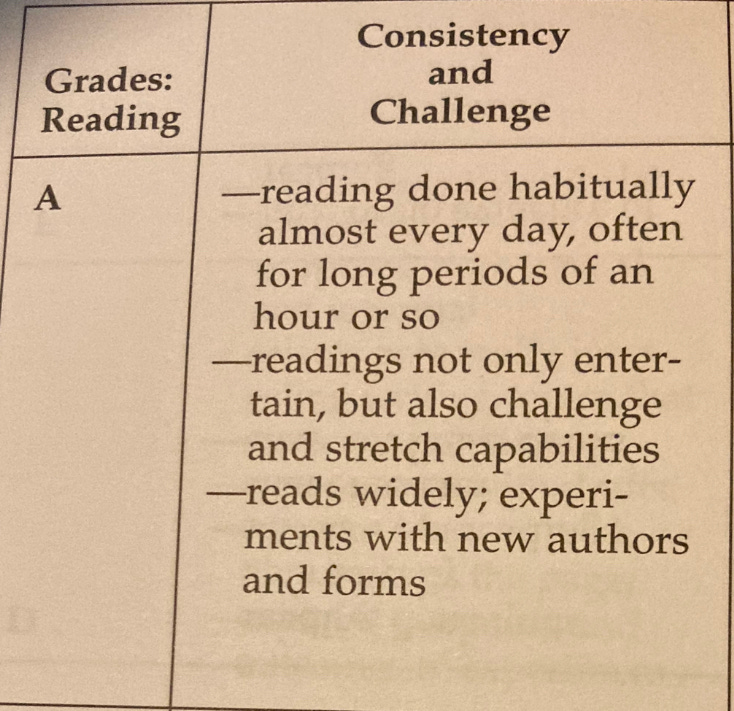

In another area of the rubric called “control of processes” students were similarly taught to understand the criteria for an “A” and experienced instruction and discussion intended to help them achieve those criteria:

The portfolio system included instruction to teach them how to use a variety of strategies and required them to document instances where they persisted with difficult passages, describing what strategies they tried and how things turned out, in journals.

Before each portfolio scoring window, students prepared their folios by writing and updating their literacy autobiographies along with reflective entry slips for work products completed during the grading period.

The portfolio strategy opened the door to legitimizing self-regulation, metacognition, introspection, reflection, and goal-setting by placing these elements front and center on the report card. Control over the selection of work to submit was theirs.

In class they were able to work with their teacher and their peers to prepare their folio submissions. They could include letters of recommendation written by their teachers and their peers.

A jury of teachers would do the grading. The regular approach to documenting reliability of scores in performance assessment is to ask two independent raters to score the work and then look at the agreement between the scores. In this project the classroom teachers recorded the grades they would have issued to each student before the scoring. I calculated a correlation coefficient to determine the level of agreement between the examiner grades and the teachers’ grades. This statistic was consistently above r = .8, often above r = .9.

Each portfolio was assigned to a primary judge who would highlight criteria on the rubric for the student’s benefit. If the primary judge was torn between scores, they could ask for a consult with another judge. The primary judge would write letters to students explaining how the evidence supported the judgment.

Then, as now, I was fully aware that tests and grades are powerful motivators and that objective, reliable, and valid evaluations of learning outcomes even by way of multiple choice tests are pragmatic necessities in a world where professionals must know beyond a reasonable doubt how to wield a scalpel or design and build bridges or teach children. I was also aware that years would pass before these students would face a licensure exam.

Middle school could be the place to teach learners how to self-regulate, to discover their interests and strengths, to downshift and employ cognitive strategies, which the portfolio teachers taught explicitly in mini lessons, often around short stories, articles, or poems.

It could put students in touch with the innate drive we have that we satisfy only through getting better, getting stronger. Relocating the power to issue grades, scary for the teachers and the students during the first trimester, brought a desire among the portfolio teachers to co-create teaching strategies, to feel the internal satisfaction of getting better, getting stronger as teachers.

Through reading and discussing the research on academic motivation in psychology in a seminar in my doctoral program, I gained insight into scientific knowledge about motivation and learned about evidence supporting the theory that motives are either externally or internally generated. It seemed plausible that motive has a lot to do with how a student reads and whether a student will even read, much less read closely.

Goal-orientation theory explained academic achievement motivation in a useful way. Dweck and Legget (1988)1 tapped into a research agenda twenty years in the making and distinguished two primary goal orientations: 1) an ego or performance orientation prompting academic effort to gain approval, to advance socially or economically, to prove one’s superiority, and 2) a task or mastery orientation prompting effort to improve an ability, to get better, to see more clearly, to enjoy a sense of accomplishment, to experience internal satisfaction.

In 1972 Edward Deci built upon research from the 1960s and published a finding that undergraduates who enjoyed solving puzzles without external reward lost their intrinsic motivation when rewarded. When people are paid to do something they previously did for enjoyment, they do it less often.

Isn’t this precisely what schools do? Do we not increase the social salience of gold stars, praise, report cards, grades, and test scores year by year? Do we not see a decrease in voluntary reading as the school years go by?

While the research showed that extrinsic motivators can diminish intrinsic motivation that already exists, the research was silent on the question of creating intrinsic motivation. Also, the research did not establish that extrinsic and intrinsic rewards are orthogonal. People can be motivated through extrinsic rewards and find intrinsic satisfaction in their improvement. Perhaps a strong motive to perform well at Carnegie Hall coupled with a deep joy in practicing scales together with genetic gifts explains musical virtuosity.

Several years before my dissertation I taught fourth graders who struggled with print as well as those who breezed through print. Too many of them wouldn’t pick up a book voluntarily for love nor money. It took my calling a parent to get the most hard core of them to comply. Then they did so grudgingly. ‘Ok, I’ll read, but I ain’t going to like it.” I could win for the moment but lose what I really wanted—to transform them into voluntary readers.

Ten years later, reading Carol Dweck’s research alongside Deci provided me with reasonably certain knowledge that I could build upon. I suspected that a lopsided emphasis on incentives from outside (grades, scores) was a systemic problem with harsh consequences for poor and minority children for whom extrinsic rewards may not hold much meaning.

I had read about and participated as a teacher of low-socioeconomic children in reading incentive programs like the stick-the-principal-on-the-roof ploy highlighted in a professional newsletter in which children who read at home for a certain number of minutes and got a parent’s sign off as proof got points which, if the school total reached a certain number by such and such a date, meant the principal had to climb to the roof and sit there for half an hour or something. There was the program where if a student read a certain number of books as certified by their teacher, they would get a certificate and a personal pizza from Pizza Hut. I scoffed: “They should give them a book for eating pizza.”

For my doctoral dissertation, I studied middle school students over a full academic year to discover whether a portfolio assessment system designed to make a task or mastery orientation more salient might increase levels of intrinsic motivation orientation. I also wanted to find out whether students who increased their level of intrinsic motivation in fact increased their reading achievement. Teachers could deliberately set out to teach students to take up an intrinsic goal orientation by making it a priority learning objective, teaching to it, and grading it.

I had read a lot of research from the anthropology of education and understood that ideas like the zone of proximal development, situated learning, apprenticeship learning, legitimate peripheral participation, and cultural-historical activity theory viewed learners as agents whose motives could be nurtured.

Children with little motivation to read, I learned, came from homes where storybook literacy wasn’t happening, where academic role models were far and few between, where mistrust of schools floated in the air. As a child coming from a poor rural Midwest family with 13 children in the 1950s, I had some personal experience to draw on.

Children with strong motives to read came from homes where books were birthday presents, where parents modeled reading and read to their children, where as my friend Steve Bialostok documented in his dissertation affluent parents pass on to their children a cultural model of reading as moral behavior that makes us better human beings.

I found myself at a middle school with three courageous English teachers willing to hand over the authority to rely on the power to grade and to implement a portfolio system designed to increase the intensity of intrinsic motivation. I passed my qualifying exam at the university. My dissertation proposal was accepted. I had a principal who not only agreed to the proposal, but gave me access to students in three traditional classrooms to use as controls. I would give 200+ students a motivation orientation survey at the end of the school year and see where the evidence led.

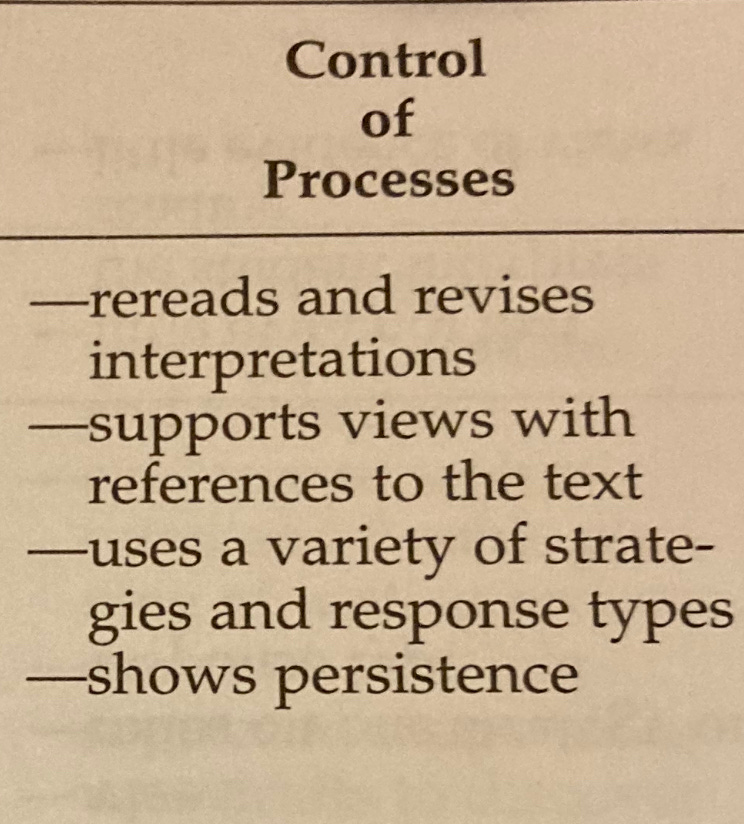

The survey I used was an adaptation of an instrument from previous research which produced quantitative data on three dimensions: advancement, approval, and intrinsic (learning). The survey consisted of 24 items, 8 for each dimension. Each item began with the stem “ In my English class when I exert effort it is usually because…” with a Likert scale from 1-5, 1 being ‘never’ and 5 being ‘always.’ An item for approval would read “…usually because I want my parents to be proud of me.” An item for advancement would be “…usually because I want to get a good grade.” For intrinsic it would be “…usually because I want to improve my ability to experience the power of literature.” The range of possible responses summed across 8 items for each dimension is 8-40, 8 being “never” across the dimension, 40 being “always.”2

The following screenshot summarizes the means and standard deviations (highlighted) for the portfolio and no portfolio classes at the end of the school year:

The left column depicts statistics for the portfolio classrooms, the right column for the traditional classrooms. Unsurprisingly, the strongest dimension for treatment and control groups was advancement. The high means of roughly 33 with similar standard deviations suggest that if I had surveyed the entire school irrespective of pedagogy, I would have found that students exert effort because they want to go on to the next grade, they want someday to get a good job, they want to earn credit, etc. The external advancement mechanisms embedded in the culture of schooling in society are powerful .3

Can you imagine teaching without grades? It’s all but impossible for me.

The least powerful motive is exertion of effort for approval, again almost identical irrespective of treatment or control experience over the course of a full year. Approval may well be stronger than advancement in the primary grades and diminish in high school. Advancement may increase in intensity in high school.

But there was a statistically significant difference on the intrinsic (or learning) dimension. With a mean of 27.86 for the portfolio students and 25.91 for the non-portfolio students—nearly 2 points—on its face students in the portfolio group appear to have grown stronger intrinsically than their controls, though marginally. A multifactorial analysis of variance was statistically significant for a main effect with some interesting interactions as well. Males in the portfolio group showed a greater difference in comparison to males in the traditional group than did females. Said differently, males may need portfolio assessment in English classroom more than females.

(NOTE: I published the quantitative findings with an ethnographic account in a book4, a chapter in a book5, and an article in a journal [see footnote 3], each referenced below for anyone interested. I would be happy to respond to email questions or comments as well.)

I don’t have space to explain the ethnographic findings in this article, but they are discussed in each of the three publications. My point here is to illustrate through my experience with Science the potential of Science to improve pedagogical outcomes regarding motivation,

In this case, the pedagogical shift came in viewing academic achievement motivation as a learning outcome not a given, designing a robust ecologically valid assessment system, engaging the professional community of local teachers in examining student work according to common grading criteria, grading bodies of work over time on both process and product rather than frequent grading of discrete assignments, relocating the authority to issue grades from individual teachers in isolation to a jury of teachers, redefining the role of the teacher from task master to coach, increasing the student’s agency to define and pursue learning goals within the parameters of the discipline, ensuring the reliability of judgments through defensible statistical and qualitative methods, and granting authority to students to demonstrate their habits of mind as readers, writers, and learners.

I don’t have space to discuss findings that reveal evidence of learning that favor the portfolio students on performance achievement measures, but those are published elsewhere as well. It’s worth pointing out that the students in both the treatment and control groups experienced broadly similar instruction (core literature, self-selected reading, writing pedagogy derived from the state direct writing assessment methods).

The Science of Reading in 2022

The science of reading has a history of internal disagreements as the scientists who study it went back and forth over the past century debating “best practices” in formal instruction. If you were to have observed beginning instruction in the early part of the 20th century, you would have seen children doing drills and exercises using materials like Noah Webster’s Blue Back Speller and McGuffey’s Eclectic Reader. Synthetic phonics from the bottom up was the order of the day—letters became sounds became words became decoding and recoding words into sentences. Comprehension was not on the radar, motivation to learn even more distant on the horizon.

“The role of the learner in this period was to receive the curriculum provided by the teacher and dutifully complete the drills provided. The role of the teacher was to provide the proper kinds of drill and practice. In this period being able to read meant being able to pronounce the words on the page accurately, fluently, and, for older students, eloquently” (Pearson, 2000, p. 153-154).6

But even then disagreements existed, rooted in the mind-numbing nature of the work young children experienced in school, precisely the sort of work that would fit neatly inside the factory metaphor for schooling waiting down the years.

A reform effort dubbed “words-to-letters” rearranged the chickens and the eggs in the scope and sequence of the early reading curriculum. Children were to learn whole words by sight first and then decompose the words into letters, an approach known as analytic phonics. The alphabetic principle itself was not the site of contest, rather the pedagogy.

During this era the assessment of reading also underwent reform. William Gray developed his oral fluency test wherein teachers listened to learners read aloud from paragraphs graded in difficulty and made judgements about reading performances.

Emerging also was the notion of silent reading. Tests purporting to measure reading comprehension using multiple choice questions generated reading scores independent of teacher judgment, “…fitting the demands for efficiency and scientific objectivity, themes that were part of the emerging scientism of the period” (Pearson, 2000, p. 156). Mirroring these tests, multiple-choice tasks made their way into reading pedagogy. Testing became conflated with teaching.

In the 1920s and ‘30s interest in judging the level of challenge children would face during reading led to the creation of readability formulas. Textual challenge increased, so the thinking went, as average sentence length increased and average number of syllables per word increased. There is some logic here in that long sentences tend to have more complex syntactic structures and long words tend to occur less frequently and can be more difficult to decode.

But the cognitive revolution later in the century put the lie to these formulas. Factors such as prior knowledge of topic and genre, specialized vocabulary, and motivation and purpose for reading made it impossible to discern level of challenge from linguistic features alone. Nonetheless, these formulas became the basis for text selection in basal readers for decades.

The idea that reading deficits could be remedied or “remediated” gained purchase during the 1930s and still has its advocates today. Coming from a metaphor of medicine, the ideas also fits neatly into the factory metaphor.

“The hope is, and always was, that if we could just find the peaks and valleys in each child’s profile of reading skills, we could offer focused instruction that would remedy the weaknesses and bring him or her (mostly hims, as our actuarial data suggest) into a kind of skill equilibrium that would enable normal reading” (Pearson, 2000, p. 158).

In my mind, debates within the science of reading fall largely within Brian Street’s conception of autonomous and ideological models of literacy. If reading is an autonomous, culture-free matter of decoding words and building mental models of texts in symmetry with the message encoded by the author, researchable questions like ‘What is the optimum sequence for teaching vowels?’ or “What is the better method for teaching students to locate details in texts?” ought to drive scientists. If reading is an ideological matter of values and cultural practices, researchable questions like “How do we create a pedagogy to teach children of poverty the intrinsic motivation required to read challenging texts?” ought also to drive scientists.

In 2022 we have come to a place where the tension between reading as a technical matter and reading as an ideological matter is forcing teachers to take sides once again similar to the reading wars of the 1980s. We face the problem of autonomous pedagogy vs. ideological pedagogy, teachers on remote control under surveillance vs. teachers with what Linda Darling-Hammond called professional accountability, an internal awareness that teachers make decisions on behalf of children with implications for their entire lives.

Unfortunately, the phrase “Science of Reading” has today become a sort of trademark for the autonomous model and is entangled in the commercial production of instructional materials, high stakes external testing, expensive professional development of teachers, and adversarial supervision of teachers with demands of fidelity.

As a hegemonic epistemology, it shares characteristics with oppression, rewarding adherents, punishing resistors. Like hegemony everywhere, the tragedy comes in the erosion of agency, in this case the professional agency of teachers who can be scientists in their classrooms, questioning their methods collectively, experimenting, doing teacher research projects, becoming vigilant observers in search of local evidence, co-creators of pedagogy that need not be a panacea nor replicable for all time in all places as we would expect of, say, physics or meteorology.

Practicing an instructional method that would lead young people to open their eyes critically to the world around them, including the hypocrisy and hegemony of their more powerful elders, Socrates warned against using reading and writing as teaching materials. He cautioned that words written down would take on power and authority without accountability. Instead of questioning writings, young people would come to see them as vessels carrying truth. Those with political power charged him with heresy for creating spaces of critical analysis where young people pushed back against hegemonical epistemology and sentenced him to death for the crime of corrupting the youth of Athens.

I remember the days of the Open Court police in California when fidelity to the manual was enforced by district coaches. Open Court was a basal reading series touted as systematic and scientific. A teacher I knew was written up because she did not have the Open Court teacher’s manual in her hand when an observation was made. The manual contained scripts teachers read from—teachers as dummies on a ventriloquist’s knee—sometimes with expected responses from students and ideas for how to handle them. Some regular classroom teachers who had previously worked joyfully and collaboratively with colleagues were lifted to positions euphemistically called “coaches” and, given special privileges and incentives, functioned as spies.

The Science of Reading for over a century has been central to advancing knowledge valuable to teachers, me included. In the late 1970s I used William Gray’s oral fluency test to great advantage. In the 1990s I used scientific theories from the cognitive revolution of summarizing as the foundation for facilitating a History Department faculty to engage in an authentic, motivated search for pedagogy. They themselves gave all of the learners in the school the same passage to summarize at the beginning and the end of the year. They participated in writing the rubric to score the tests and selected anchor papers. They talked in the lunch room and at the copy machine about their work. They read and discussed scientific studies of comprehension with me in retreats. There were considerable benefits for adolescent learners from the poor side of the tracks. A future without this science would be tragic.

But even the most productive scientific researchers in the field are concerned that the definition of science has been narrowed; in some quarters studies done outside of an experimental, quantitative design are viewed as unscientific. A recent panel of researchers published an article urging others in the field to reconsider and open the aperture so that Scientists can answer their questions about reading using the most suitable design for the question, not the designs that require questions only numbers can answer.

Teachers are in the best position to know when it is raining in their classrooms. Children are right in front of them. They desperately need Science to help them understand things beyond what can be learned from experience, but they must have the right and responsibility to work as teacher scientists according to their own professional lights with their colleagues to create classrooms where children learn not just to decode words, to mouth them, but to understand them and challenge them and to reject them in the light of good faith critical thinking.

Dweck, C., & Leggett, E. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256-273.

Hayamizu, T., & Weiner, B. (1991). A test of Dweck’s model of achievement goals as related to perceptions of ability. Journal of Experimental Education, 59(3), 226-234.

Terry Underwood (1998) The Consequences of Portfolio Assessment: A Case Study, Educational Assessment, 5:3, 147-194, DOI: 10.1207/s15326977ea0503_2

Terry Underwood (1999). The Portfolio Project: A Study of Assessment, Instruction, and Middle School Reform. Published by NCTE, the National Council of Teachers of English.

Murphy, S. and Underwood, T. (2000). Portfolio practices: Lessons from schools, districts and states. Norwood, MA: Christopher-Gordon.

Pearson, P. D. (2000). Reading in the 20th century. In T. Good (Ed.), American Education: Yesterday, today, and tomorrow. Yearbook of the National Society for the Study of Education (pp. 152-208). Chicago: University of Chicago Press.