Spring in Washington DC is a magical time to convene a conference of academics. The air is chilled, perfect sweater weather, the biting cold of January has gone, and the streets are perfect for strolling.

In March, 1980, the annual meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication was held there, and Christopher Hayes was to present a paper1 on a theory of reading that had bubbled up in the cauldron of linguistics, a theory of reading spawned in juices served up by Noam Chomsky two decades earlier with his theoretical and conceptual framework for grammar and syntax called ‘transformational grammar.’

Chomsky rejected both traditional and structural grammar as an explanation for what people must know and be able to do to discern the difference between ‘dog bites man’ and ‘man bites dog,’ to evaluate the sentence ‘colorless green ideas sleep furiously’ as nonsense despite its structural legitimacy, to embed chunks like ‘a city that is beautiful, ‘a city in spring,’ and ‘a city where the CCCC is holding its annual conference’ into ‘the CCCC is holding its annual meeting in the beautiful city of Washington DC in spring.’

Chomsky theorized that language has two levels, a deep and a surface level, a deep system of psychological components like grammar, syntax, and semantics that afford us tools to generate and interpret surface expressions. Phonemic and graphemic signs and symbols skate along the very surface of the surface level. The traditional question asked by researchers in reading pedagogy pre-Chomsky was something like ‘How do readers process printed words to render them into spoken words?’ Chomsky asked a different question: ‘How do individuals get from the depths of language meaning to the surface expression of a message, and its correlated question, how do we get from surface expressions to the deep substance of language?’

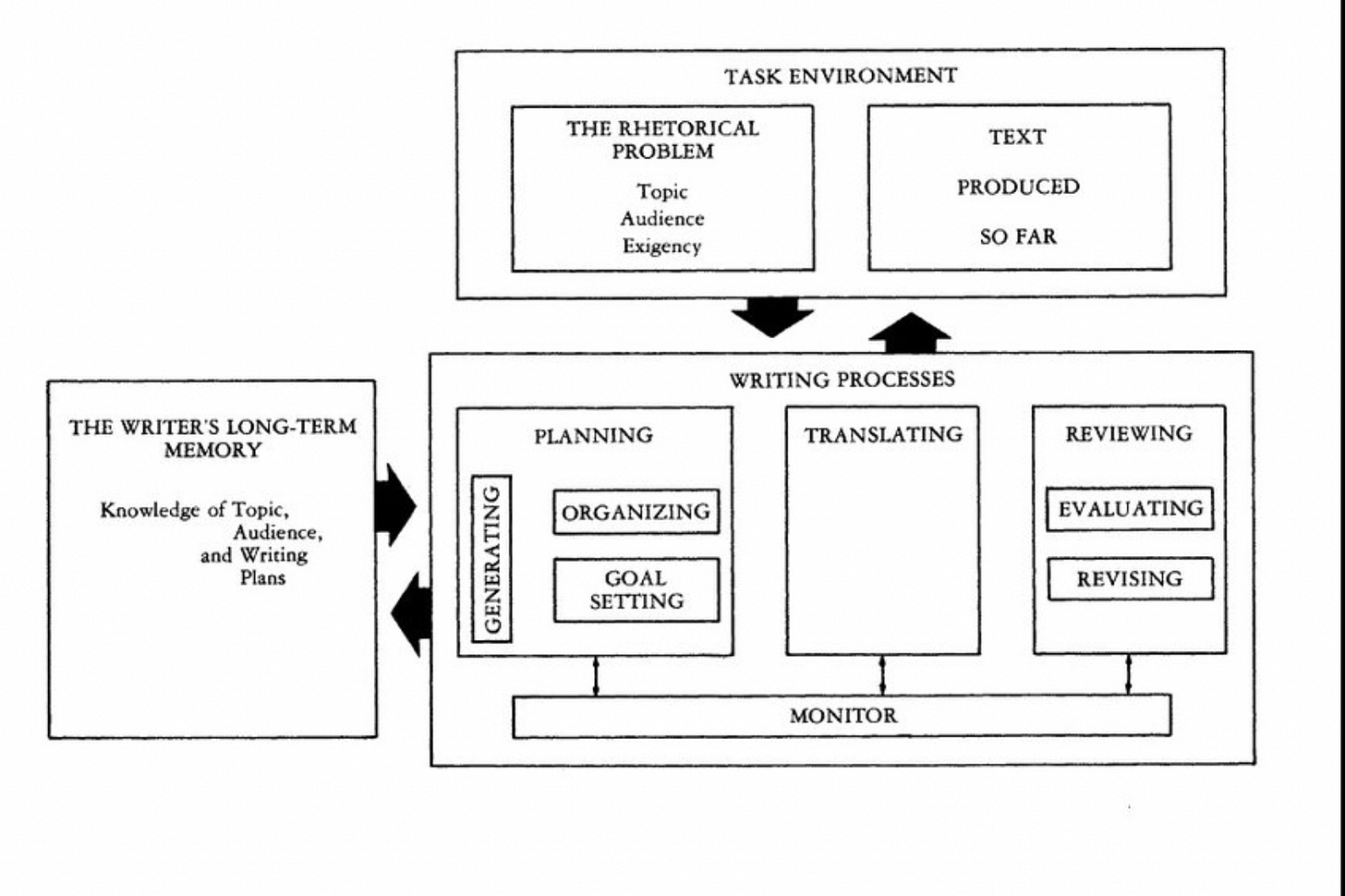

These questions were then infused into emerging conceptions of reading and writing from the perspective of cognitive psychology. To explain the writing process, theoretical models like Flower and Hayes (1980) were created. In this model the depths of language are implied as being situated in long term memory, and the activity of writing is set within what future theorists might call a sociocultural surround. No where in this model are the technical, surface issues of spelling and punctuation addressed. Note also that the act of writing is future oriented (text produced so far provides the ground for text to be produced in the upcoming hours).

Christopher Hayes wasn’t talking about writing in his paper that spring in DC, but he was talking about a related, new view of reading that sought to explain the kinds of thinking it requires to link deep knowledge about language and the world with comprehension of surface expressions. Hayes turned to the work of Kenneth Goodman, who had been doing important work on a psycholinguistic view of reading. Vygotsky’s distinction between language (words) as a cognitive tool to use privately in the intensional or subjective world vs language in the service of communication in society in the extensional or objective world applied. Encoding and decoding vis a vis spelling and phonics, prioritized in dominant theories, are instrumental for reading and writing but hardly the heart of the matter.

Hayes made this very point to his audience of university composition and communication professors primarily to assure them that colleges need not worry about teaching phonics. Goodman’s theory pointed to the need for college students to experience instruction in moving from print to meaning, not from print to speech:

Christopher Hayes had been exploring the literature on reading enough to arrive at some firm conclusions. It made sense to him to believe that readers are future-oriented, that they must predict what lies ahead semantically and syntactically in the text before they gaze on the printed words to come, not automatically pause on individual words in immediate focus on the surface of the technology of print until they are certain of a pronunciation before moving on. Goodman had used the term “cue systems” to describe psychological tools applied during reading. ‘Dog bites man’ differs from ‘man bites dog’ because the syntax of the language cues the reader to understand the object of the verb differently. ‘Dog bites dog’ differs from ‘man bites man’ because the semantics of the language contextualize the verb in a much different sense:

Hayes underscored the Vygotskian importance of seeing the word as a unit of verbal cognition apart from speech, a unit functionally not a spelling or pronunciation stripped from semantics, by discussing research completed in the 1960s. Researchers in comprehension have long used a subject’s memory for words as a yardstick in experiments to test theoretical propositions. Witness:

Of course, repetition of exposure of the same spelling would logically produce stronger memories for the word. Koler, however, was testing students who were bilingual in English and French. If the list were something like ‘man, woman, person, camera, tv, desk, snow’ vs ‘man, woman, person, snow, tv, desk, snow,’ hands down more subjects would remember ‘snow’ than ‘desk.’ But how do we explain the sequence ‘man, woman, person, snow, tv, desk, neige’ locking the word ‘snow’ in memory more securely than ‘desk’? Semantics, my friend.

The kicker came from additional work Koler had done:

Hayes made a strong case against phonics in college for readers who fail to comprehend their reading assignments while bolstering the case for attention to semantic feature analysis and instruction in complex syntactic structures. Inadvertently, apparently, insofar as he was addressing an audience of college faculty, not of elementary faculty, he also made a strong case against ignoring the significance of syntax and semantics in early reading instruction. Developing habits of mind intermingling the components of language at the deep level rather than privileging the graphophonic system at the surface to the exclusion of syntax and semantics may be the way to go. Note: Neither Christopher Hayes nor Ken Goodman argued against phonics instruction.

SoR advocates, who speak so darkly about naive and romantic liberals with their joyous reading pedagogy in the early grades enacted as a guessing game, may not have a full grasp of language as a complex system of interlocking parts requiring prediction and estimation as ongoing cognitive strategies keeping the reader on track. They see their six inches of the elephant as the whole friggin’ elephant. Spring, 2023, would be a fine time for political leaders gathering in Washington DC to question the wisdom of the David Coleman’s and the Chester Finn’s and the dyslexia crowd.