For the past week I have been looking high and low for something I read thirty years ago that carried an insight to me from almost a century ago, which tilted my paradigm at the time. Where did I read that?

Vygotsky and Alexander Luria, two Russian psychologists working to explain the role of history and culture in the development of cognition, wrote about a research expedition to Soviet Uzbekistan where farm workers living an ancient life on high mountains, who had little experience with school, coexisted with students studying at a teacher’s college.

The purpose was to do natural experiments in classification, concept formation, and problem solving, to see if the rapid pace of modernization in Russia had systematically altered the cognitive tools people used to map their intensional worlds.

It was a tip of the cognitive tongue moment of massive proportions, a frustrating senior moment. I couldn’t remember where I read about those farmers and their responses to the classification experiments Luria carried out. Worse yet, I couldn’t remember the substance of the particular experiment that fascinated me half a lifetime ago.

*

“I can’t remember what it is, what you call it,” she would say. “What did I want to say? Oh, for heaven’s sake.”

“What does it have to do with? Gardening? We were just talking about how pretty your flowers were when you lived in Ventura.”

“No, I don’t think so… It wasn’t about my flowers…”

*

Word retrieval can be an intellectual challenge under the best circumstances, not a simple matter of memory. Searching for the precise term for a delicate or complex matter can be a perfect opportunity to think carefully and even to learn. We may not yet know the word for which we search; the meaning of a word we retrieve easily may be imperfect or superficial.

In the case of the chunk of meaning for which I searched, the word “Luria’s experiment” guided me to a pallet of meaning, but I could not unpack it. I needed the support of print, which meant I needed the support of a title and facts of publication—tools of retrieval from an external storage space.

A word’s meaning intersects with the meanings of other words in labyrinthine ways. “Since word meaning is both thought and speech,” Vygotsky reasoned, “we find in it the unit of verbal thought we are looking for” (Thought and Language, p. 6) to target for answers to psychological questions. Word meaning, accordingly, is the distinctive feature separating words from the mouths of humans from “…the swearing of the ‘learned’ parrot” (p.93).

*

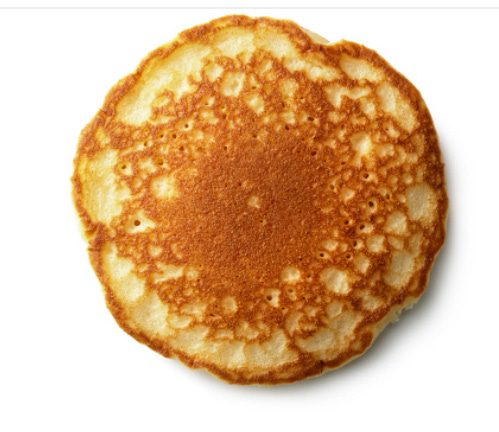

Word retrieval, i.e., accessing a word in its linguistic wholeness such as it is from memory, is an issue not just on college aptitude vocabulary tests, but in rehabilitation therapy for stroke victims.

As college entrance exams seek to identify individuals with strong verbal knowledge and intelligence using the word as the cognitive target, rehabilitation therapy seeks to stimulate the strong cognitive effort needed to restore lost neurological capacity to retrieve words and bring them from deep storage in semantic networks through application of psychological tools (questions) to the point of oral articulation (speech).

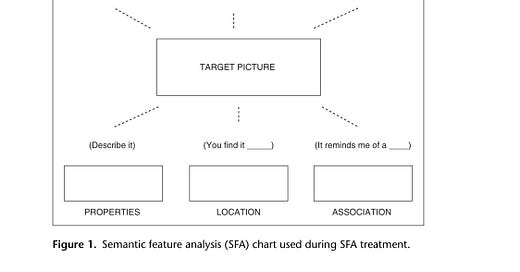

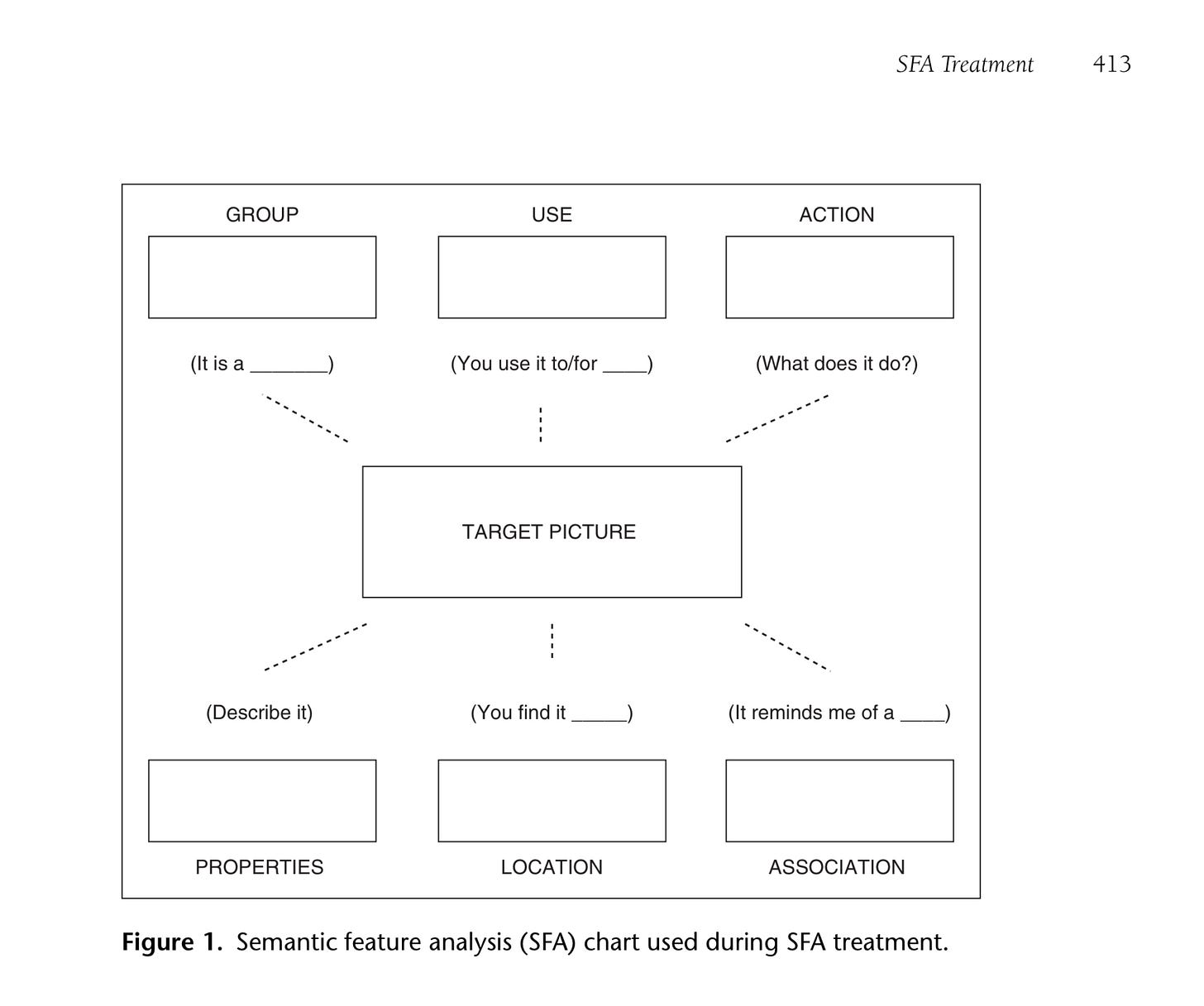

According to Boyle (2010)1, since the 1980s studies in therapy for stroke victims using semantic feature analysis, or looking at the aspects of a word’s meaning to unlock its pronunciation, have documented the efficacy of such treatment protocols for aphasics who experience such problems in a severe manner. Boyle published a worksheet for application clinically in speech pathology in a review of the literature that illuminates the structure of psychological tools common in the therapy:

For example, just for kicks, let’s take a look at a sample target picture used in therapy. Chances are good that word retrieval will happen almost instantly, but if it doesn’t use the psychological tools arranged in the diagram:

It is a food we make to eat with butter and syrup at breakfast time… it is a.,, Chalk one up for picture walks as prereading activities. Spreading activation magnetizes a whole plate of front burner words from butter to syrup to blueberries and bananas.

Boyle compiled compelling evidence supporting the use of the SFA treatment in aphasia, but the topic is far from saturated with empirical studies. For example, although researchers know that SFA therapy results in transfer of measurable skill in word retrieval from target pictures of specific nouns to better retrieval of nouns in general, such is not true for verbs. Nobody seems to know why, though I believe I have a great hypothesis grounded in Piagetian theory. Boyle does an excellent job of explaining how lexical retrieval occurs:

*

Word retrieval is the reverse of word decoding. Having a meaning in mind but missing the phonological instructions to activate speech articulation stands in mirror image to having the phonological instructions from the printed letters activating speech production but still knowing potentially little if anything about the meaning associated with the word.

Word retrieval is instrumental in writing and helps us figure out what we want to mean, though mental drafting can end well before activating orthography when we consider but discard a word. Writing pedagogy that asks learners to keep records of important words considered but discarded can generate great discussions among budding writers.

Word decoding is instrumental in reading, with mental modeling of a word’s sense often ending before pronunciation (silent reading). Word retrieval as a tool of verbal thought is a semantic phenomenon involving analysis of meaning; word decoding as a tool of verbal thought is a phonological phenomenon involving analysis of sounds.

*

Consider this word problem. We have three words inner voiced—sauté, deep fry, broil. Pick two to group together. What features do they share? What excludes the third? Pick another two; answer the same questions.

Search for a contrasting trio. Freeze, desiccate, can. Internally analyze their features; identify features different and alike vis a vis each trio. Semantic feature analysis can happen at lightning speed.

It’s pretty clear why semantic feature analysis as cognitive behavior is important in literacy pedagogy. Teachers use it day in and day out incidentally or formally. Teachers have posted tons of inexpensive SFA lesson plans aligned to the Common Core for both reading and math on websites that have proliferated as traditional commercial publishers struggled to fill gaps in curriculum materials left because the Core refused to take a stand on pedagogy.

*

So I managed to find a reference to the experiment I mentioned in the intro to this post. It was hiding in plain sight on the Internet. I came upon a webpage at UPenn.edu with carefully drawn context for thinking about Alexander Luria2 and his work in cultural historical activity theory.

The experiment that startled me years ago involved Luria’s asking peasant farmers to consider pictures of four objects—hammer, saw, log, hatchet—and to divide them into two groups, one group with three, one group with one.

The farmers routinely grouped {saw, log, and hatchet} and {hammer} using practical or situational thinking—organizing by function grounded in lived experience. Although Luria tried to teach them to classify abstractly as in {saw, hammer, hatchet} and {log} in the manner students learn in school, the farmers would have none of it. The UPenn webpage cites a plethora of quotes from Luria; I recommend a quick trip there if you’re so inclined.

In this manner, with their concern for the role of society in shaping cognition, Vygotsky and Luria crossed swords with Stalin, who in the 1930s suppressed all trends in Soviet psychology not directly linked to the works of Marx, Engels, and Lenin, a suppression that blocked the world from reading Vygotsky for three decades:

“Such a turn of events…undermined Vygotsky’s research program, which relied upon such ‘bourgeois’ theories as psychoanalysis, Gestalt psychology, and the cross-cultural analysis of consciousness. …[A] group of Vygotsky’s students…[left] Moscow for the Ukrainian city of Kharkov, where they eventually established a program in developmental psychology” (Vygotsky in Context, Alex Kozulin, Editor, in his introduction to Thought and Language, Vygotsky, 1934, 1986, p. xliii-xliv).

Boyle, 2010. Semantic Feature Analysis Treatment for Aphasic Word Retrieval

Impairments: What’s in a Name?

Article in Topics in Stroke Rehabilitation · November 2010

https://languagelog.ldc.upenn.edu/nll/?p=481