Measuring Up in K-12 Classrooms: Solutions to Failures of NCLB, Race to the Top, and CCSS to Center Public Schools for Children

What do you mean by achievement?

“Traditional ‘tests and measurement’ conceptions of assessment are already hugely present in today’s classrooms in the form of high-stakes test preparation, interim tests, and the multitude of worksheets and chapter tests that imitate standardized tests. Although there are innovations such as learning progressions that could redress some of these old conceptions, the question is whether measurement and data-focused interventions are the best way for teachers and districts to accomplish urgently needed instructional transformations.” (Shepard, 2020).

A colleague shared with me a slice of recent data extracted from an ongoing qualitative study from an interview with a first grade teacher about uses of a particular set of approved curriculum materials. This colleague found it scary.

“I love the workbook,” the teacher said.

One lesson is provided on one page. Teachers provide direct instruction in the objective of the day, students are provided with tasks, and best of all, when finished, students need not provide entire workbooks—the pages are perforated and can be torn out. Everything is provided for everyone.

Students stand in line and wait for her to correct their work (in his podcast here on ltRRtl Justin narrates his experience with standing in line in class). This teacher relies on data from daily worksheets and interim tests, also provided, to organize reteaching to customize the curricular spiral already built in. Manipulatives are provided, but are too distracting, too much trouble to work with in first grade. One child threw a blue block at another child.

***

In the 1990s, when I was doing my dissertation research on portfolio assessment, I needed numbers. The whole point was numbers. We had a hypothesis; we wanted to know something. For all practical purposes, without quantitative evidence of consequences, that is to say, high-quality objective evidence ruling out the null hypothesis, portfolios were dead in the water.

Even with such evidence, they still perished as a viable strategy to attend to an even then “urgently needed instructional transformation.” I thought I had struck gold for change when the analysis of the data from the achievement motivation survey I administered turned up a statistically significant difference between portfolio and non-portfolio students on the mastery goal orientation factor. Portfolio practices increased levels of intrinsic motivation to exert effort in their English class among a diverse student population at a Title I middle school.

***

There is at least one key difference between the use of numbers and measurement during day to day instruction in a first grade classroom vs. during a yearlong study of the consequences of portfolio assessment. Teachers make decisions contingently, in the moment; they are live participants in the unfolding of a learning opportunity and need to know how learning is happening, not how much. Their focus is on making the best decisions to extend and sustain learning. They need to know what improvement, if any, was made—or if greater confusion arose. Researchers study questions of fact and theory, seeking to minimize contingency and understand predictability.

What if counting things up wasn’t the point of portfolio assessment? What if a primary reason for designing a portfolio system isn’t to add another way to sort and measure children, but to “accomplish urgently needed instructional transformations?” The question backs up on itself: It’s not “Do portfolios increase levels of intrinsic motivation to exert effort in academic settings?” We already know they do—or they can—through quantitative study. The question is this: “How can we implement portfolios locally to evoke urgently needed instructional transformations?”

“How can we implement portfolios locally to evoke urgently needed instructional transformations?”

What if a core learning outcome of schooling for children, the one thing we really should be measuring, is self-regulated learning, which is defined stipulatively here as a human organism’s competence as a participant in disciplinary academic discourse, right along with disciplinary knowledge acquisition, which sharpens expertise and leads to higher levels of participation? With self-regulated learning as the core outcome, it turns out that the instructional transformations most urgently needed by teachers are the same learning transformations needed by learners—how do we become more expert learners capable of becoming ever more and more expert epistemic powerhouses through self-regulation?

***

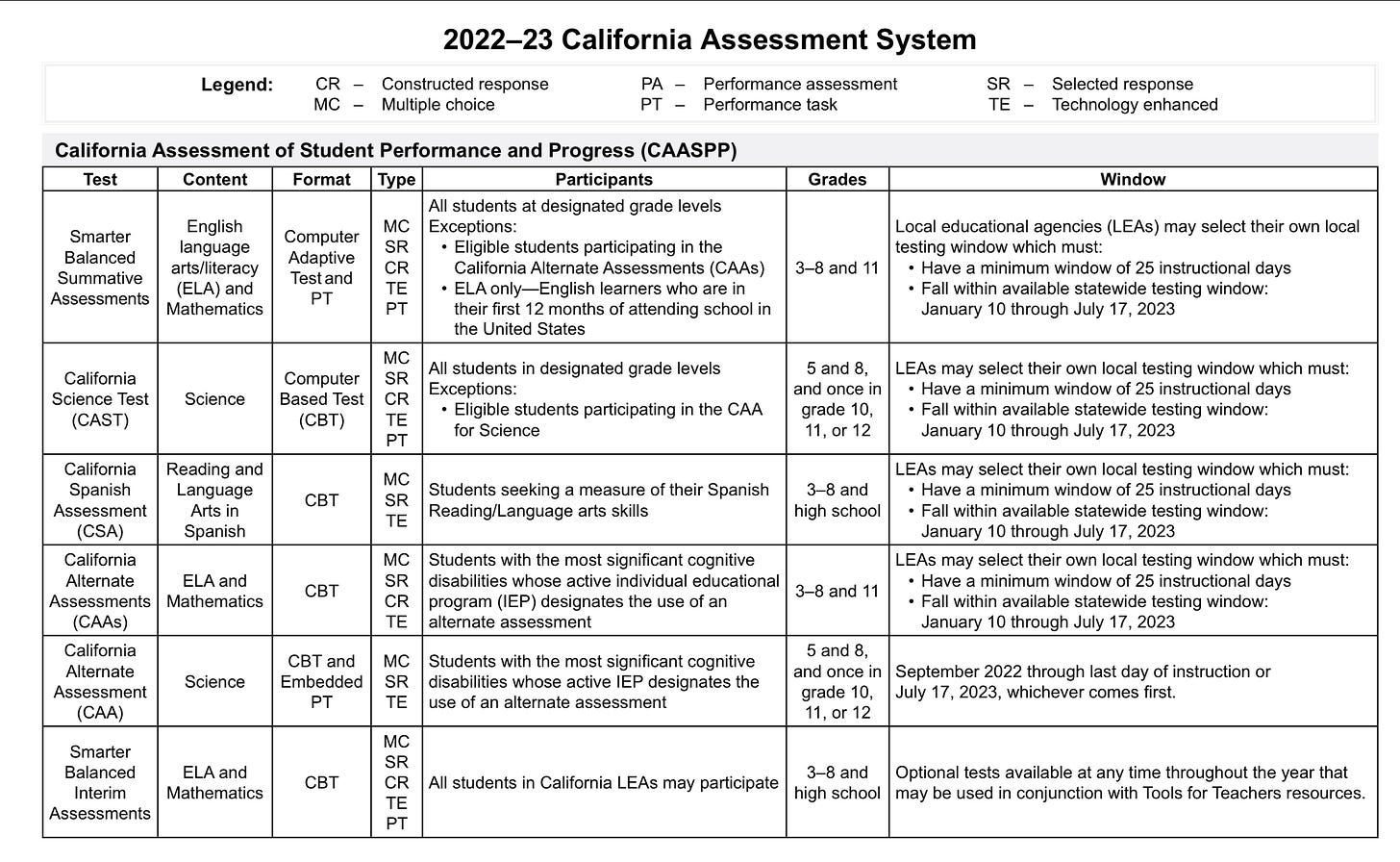

Take a look at a state calendar of interim and summative assessments under the Common Core:

Reliability anyone? Why is this a fact of school life?

***

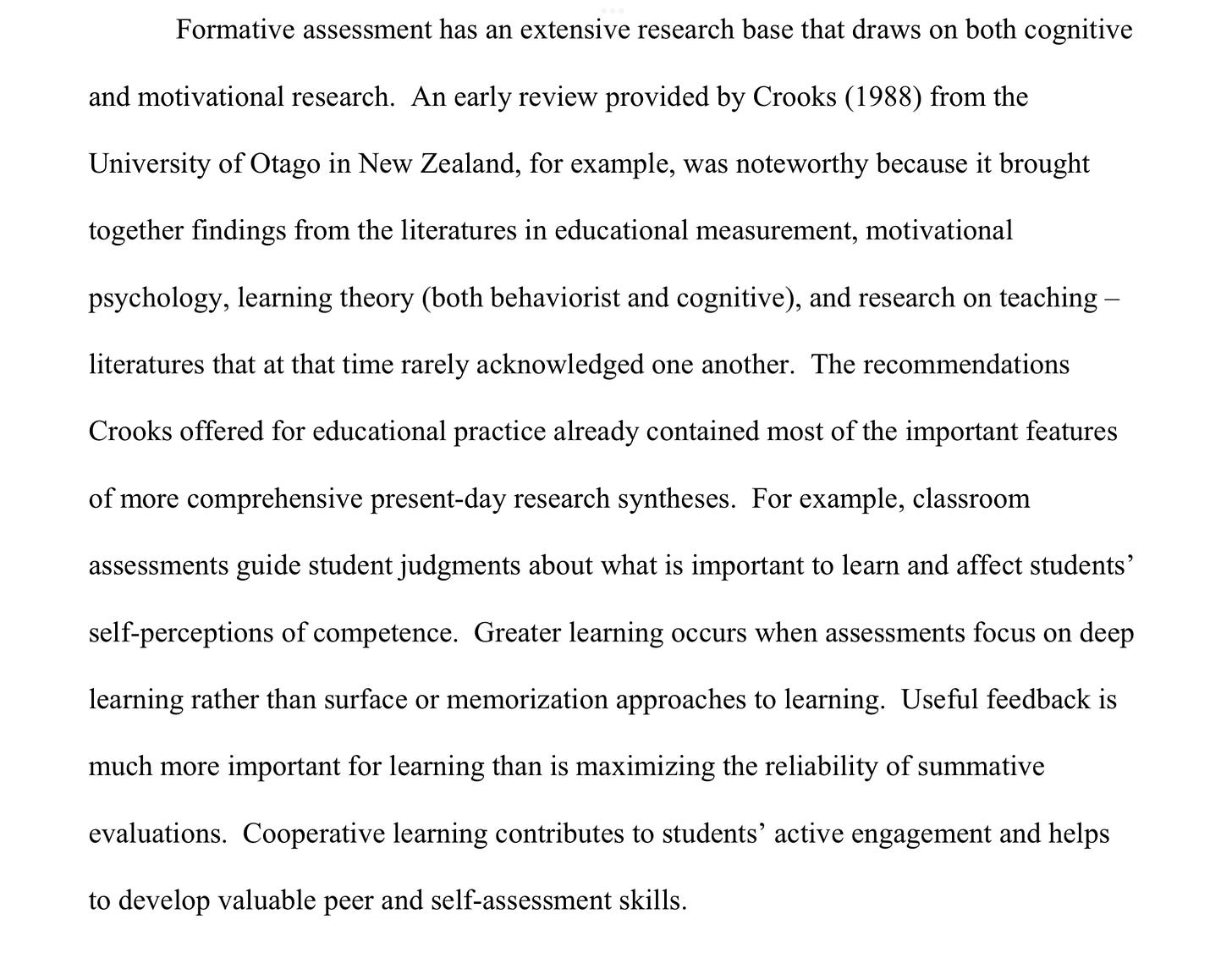

Defining ‘formative assessment’ has been an ongoing issue in the research literature. Shepard (2020), writing a chapter in a book publishing a range of viewpoints on classroom assessment and measurement, including scholars of measurement, framed her concern as follows: “[I worry] about…further intrusions of measurement into classrooms. [The] research literature tells us about the kinds of feedback that have negative effects on learning and the counterproductive effects of interim tests and data-driven decision-making (DDDM).” There’s little doubt that participation—engagement, time-on-task, doing the work, whatever word you like—is situational and sociocultural, and it lives in interactive feedback or dies in friendly fire.

In essence, formative assessment strategies when seen as mini-summative dipstick events scheduled on a calendar to see how much more needs to be stuffed in or practiced are worse than useless because not only do they not inform the teacher about what to do, they mislead children in ways that habituate learning as repetitive and idiosyncratic, driven by ability and not effort, disciplined and simple, rather than creative and complex; as problem-solving rather than problem-posing; as competitive rather than collaborative, self-regulated participation in a community of learners.

***

As near as I can tell, the past few decades in research have produced considerable evidence that successful ambitious teaching for equity prioritizes the goal of pedagogy to be teaching learners to self-monitor, self-assess, and self-regulate—and to develop a sense of ownership of learning.

These aspects cannot be explicitly, directly, systematically taught to children in an institution that values standard scores, ranks, percentiles, and levels of proficiency and inserts mechanical measurements as the driving force. As Shepard pointed out, data walls that showed up during Race to the Top to publicly shame schools and teachers by publicizing rankings seeped into classrooms and shamed those learners who most need support. Measurement has a place in education but must walk on eggshells in the ecology of learning:

“I have argued that measurement specialists have a more important role to play if they partner with disciplinary experts to address those particular assessment applications where rigorous quantification methods are required.” (Shepard, 2020).

My dissertation research provides a handy example. To examine differences in students’ reasons for exerting or avoiding effort in their English classes, I surveyed over 200 students, half saturated in portfolio practices designed to maximize self-monitoring and reflection on learning, half in a traditional assign-and-test pedagogy where students kept track of homework grades and test scores in a standardized binder. “I exert effort in my English class because I can feel myself improving as a writer” (never-sometimes-often-usually-always).

Because the curriculum was literature-based, students in the treatment and control classes were required to read from the same core list of texts. But core assignments involving whole class books were embedded in guided self-selection with peer-directed opportunities to share insights and advice. Building the portfolio was done day by day, week by week, until end-of-trimester portfolio reviews for summative assessment involving external feedback. My—our—hypothesis was that students through portfolio practices would report higher levels of intrinsic motivation than the control students. I was right.

But there were six individual teachers involved in teaching the students who were to be sampled vis a vis the survey—a dipstick kind of measurement for sure. Whether I did or did not find a significant difference in achievement motivation goal orientation, someone could argue that the presence or absence of a difference might have nothing to do with portfolios. There were six teachers behind the scenes. How would I know whether some random stroke of fate put this combination of teachers together to produce this combination of effects on the means and standard deviations of treatment vs. control distributions of scores?

I needed a way to separate the effects of the two predetermined pedagogies (self-regulated vs. teacher-regulated) from the separate random yet systematic effects of spending a year with individual teachers. A consult with a measurement specialist alerted me to the concept of “nested factors.” Crash test dummies—that was the example.

Measures of a car’s ability to protect life in a crash rely on what happens to dummies strapped into a car, which is then crashed. Data are taken from observing and counting instances of harm to dummies. But not all dummies are created equal. Measurement specialists account for defects and differences in dummies (random differences “nested” inside the factor of interest, i.e., damage to humans) and separate these random effects from the overall safety score. My six teachers were analyzed as “nested variables,” and the size of the difference between the groups was statistically reduced (the teachers did have unique effects apart from their pedagogical approach). But the difference between groups of students was still statistically significant.

***

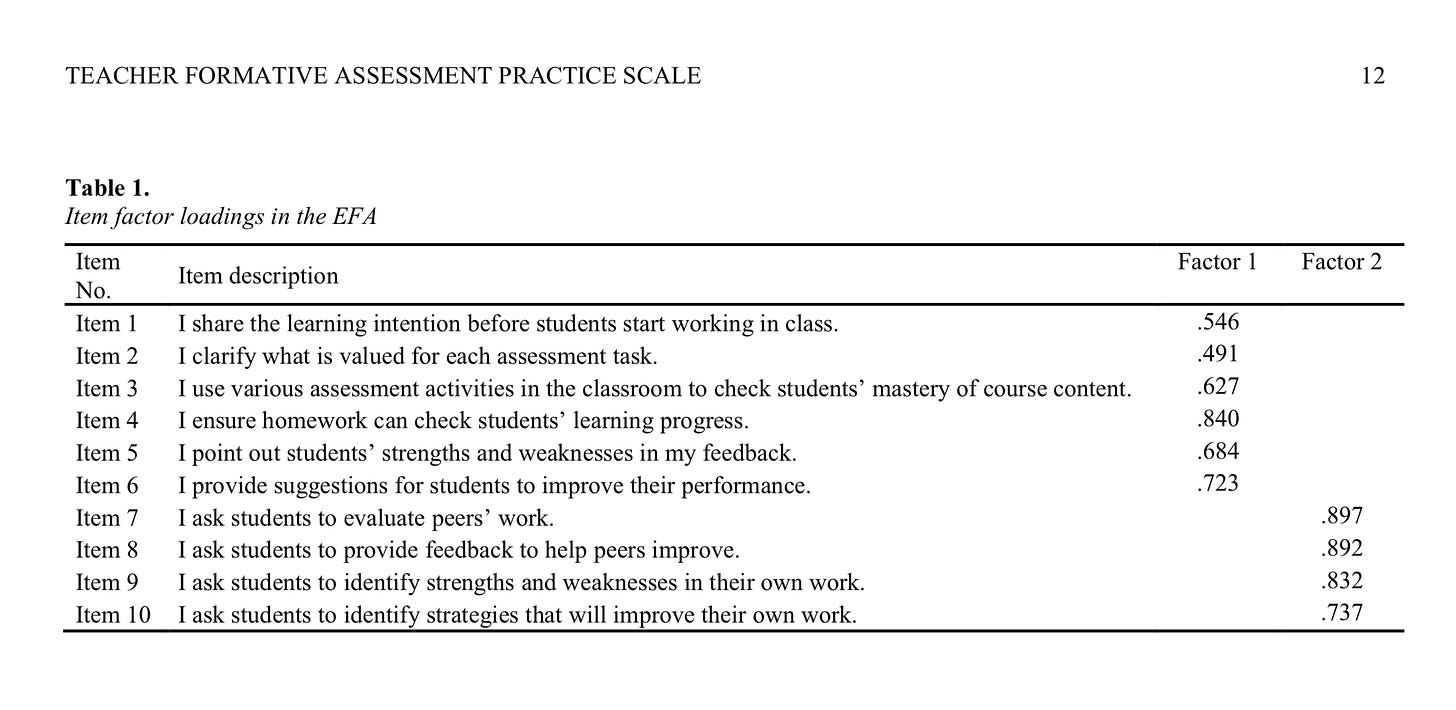

Another example of Shepard’s comment about the ongoing importance of measurement and evaluation in schooling—on not throwing the baby out with the bath water—comes from a recent research project aimed at measuring teacher practices. Yan and Pastore (2022) developed and validated the “teacher formative assessment practice scale” to be used in teacher professional development as a tool for reflective professional growth in teacher learning communities—using quantitative techniques to isolate clusters of ratings of formative assessment practices as a central aspect of pedagogy, a scale of ten items loaded on two main factors: a teacher-directed formative assessment factor (items 1-6) and a student-directed formative assessment factor (items 7-10). Witness1:

Surely, teacher-directed formative assessment is part of the conventional wisdom, a core instructional responsibility, but the language of items 1-6 are not as cut and dried as points, grades, and multiple-choice tests suggest. Choice of the word “share” to characterize item 1 encompasses both “communicate” and “negotiate” and implies a give and take, a routine discursive structure incompatible with a one-way announcement of a learning objective or a posting on a screen. Item 2 relies on teacher discernment of feedback from students; to clarify is to respond to confusion or miscommunication. Item 3 implies that teachers show a commitment to academic discourse and to the curriculum, the disciplinary discourse learners need to access.

The second factor, student-directed formative assessment, this is the new frontier, the leap into the future Shepard (2020) calls for. Yan and Pastore (2022) found quantitative evidence that two separate pedagogical factors regarding formative assessment can be discerned, one more hospitable to a scripted, point-driven, leveled classroom with workbooks with perforated pages and public shaming, the second demanding a full fledged transformation of the sort we couldn’t really imagine back in the day when the challenges of scoring portfolios reliably were taken far more seriously than the consequences of portfolios in supporting self-regulated learning.

***

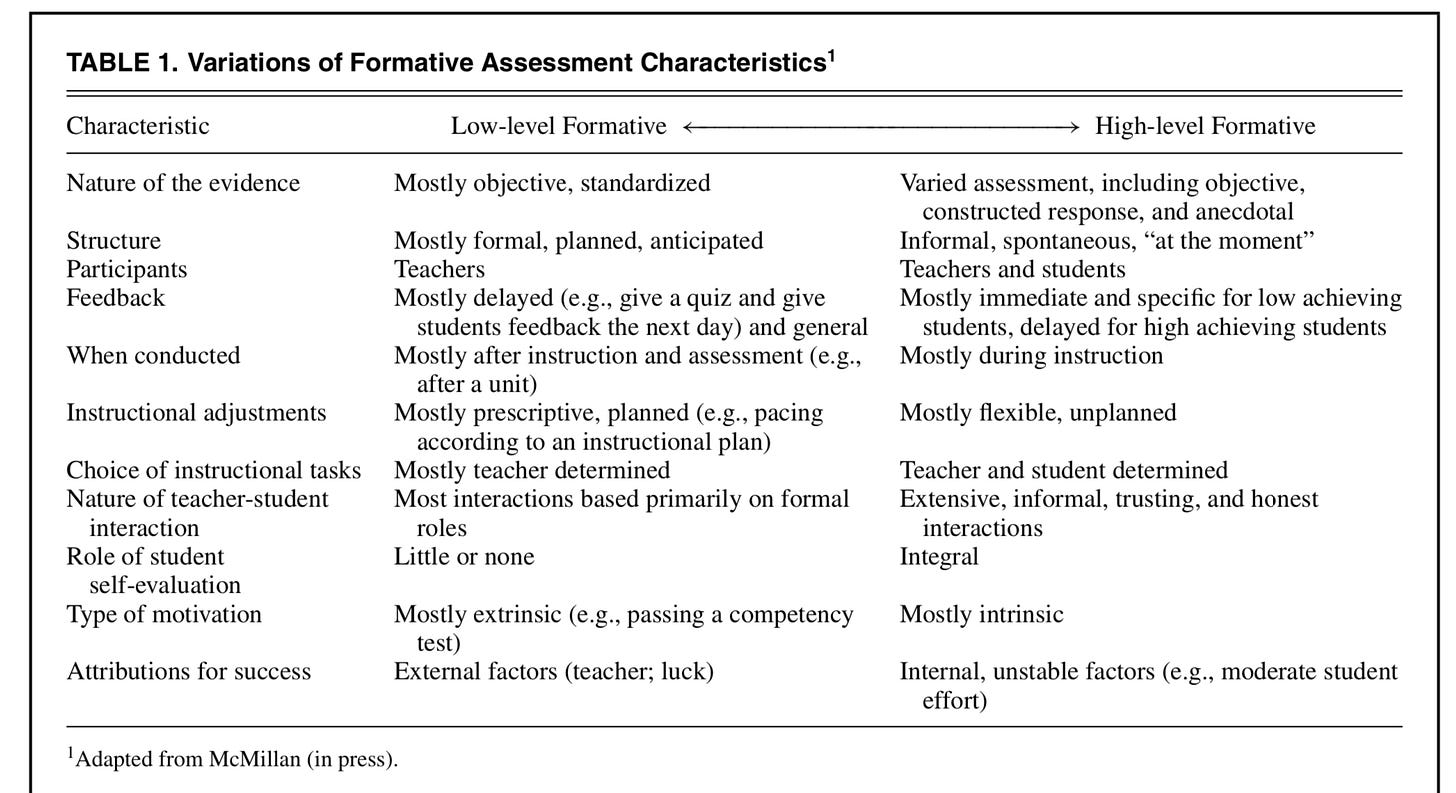

Cauley and McMillan (2010) took a crack at bringing a glimpse of the distance between low-level and high-level formative assessment in a way that casts light on how much has been learned just over the past decade about self-regulated learning. Whole language practices included “kid watching,” but by 2010 researchers are including “kids watching themselves and others” in the mix.2

Almost 20 years ago, Shepard (20053) cited Crooks (1988) to show that the fundamental idea of carefully shielding children from the negative consequences of summative assessment has long been neglected in schools as factories. I cited Crooks (1988) in my dissertation in 1996. The front burner question is not ‘why would anyone use formative assessment strategies like portfolios.’ The question is why are we not using insights into formative assessment as a scaffold for self-regulated learning in equitable, respectful learning communities?

Suggested citation:

Yan, Z., & Pastore, S. (2022). Assessing teachers’ strategies in formative assessment:

The Teacher Formative Assessment Practice Scale. Journal of Psychoeducational

Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829221075121

This is a pre-print of an article published in Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment.

Personal use is permitted, but it cannot be uploaded in an Open Source repository. The

permission from the publisher must be obtained for any other commercial purpose. This

article may not exactly replicate the published version due to editorial changes and/or

formatting and corrections during the final stage of publication. Interested readers are

advised to consult the official published version,

To cite this article: Kathleen M. Cauley & James H. McMillan (2010) Formative Assessment Techniques to Support Student Motivation and Achievement, The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues and Ideas, 83:1, 1-6, DOI: 10.1080/00098650903267784

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/00098650903267784