Biology teaches us that lifespans of organisms sprouted, hatched, budded, regenerated, cloned, or otherwise born are predictable but wildly variable, sensitive to adaptations over evolutionary periods and responsive to recurring conditions in the wild. Mayflies develop as aquatic nymphs with gills in fresh water for many months before they morph into adult bugs with wings, existing in that frenzied state from a day to a week, making reproduction a hurried affair—if a big winner in the evolutionary sweepstakes. Do it like hell any chance you get with any mayfly of the opposite sex for a few days and then die. Fruit flies take their place in the open air for a month after a ten day gestation, pressed for time to graduate from college before the grim reaping. The hardy housefly lasts as long as a month if it avoids the swatter. Monarch butterflies show off their true colors for up to six weeks.

In the mammalian world, mice live up to two years if they are very lucky and steer clear of cheese traps, medium-sized domesticated dogs up to fourteen years with tender loving care. Wild dogs, including species such as wolves, African wild dogs, and dingoes, have shorter lifespans due to harsher living conditions and lack of medical care, seven to ten years on average, though many may not survive that long against threats like predation, disease, food scarcity, and human activities. The Galapagos tortoise beats its drum for 150 years, the Greenland shark swims in icy waters for five hundred years. The bristlecone pine tree checks in at an awe-inspiring 5,000 years. Humans live roughly five to eight times the life span of a medium-sized dog.

Reflecting on the full scope of the lifespan of a writer, lifewide and lifelong, could be a productive activity for writing teachers as an exercise in appreciation of the gravity of the teaching task. In my experience, teachers spending entire careers teaching at a particular level sometimes develop blind spots in their peripheral vision. What’s wrong with that?

Perhaps one of the foundational dimensions of learning to write with the most impactful consequences on the lifespan of a writer is the learner’s attitude toward writing. Philosophers and educators for centuries have known about a strong link between writing and learning in general. Interested in lifelong and lifewide learning? You are also interested in writing. Unfortunately, a mountain of evidence I’ll review for you sometime shows that people in the United States generally would rather hit their thumb with a hammer than write.

Optimal writing instruction is carried out at all levels with a deep sense of the centrality of writing as a tool of human consciousness. This is not the norm, in my experience—though the opposite can be said of reading, the fount of wisdom. Keep in mind. Teachers have a history of using writing as punishment, as surveillance, as busywork, as proof, as a test, a gauntlet. When it is celebrated, trophies or certificates or grade points or other surface rewards can trivialize the effort. Alexander Bain, I’m sure not intentionally, saddled writing teachers with the radioactive five-paragraph essay, guaranteed to turn even the most exciting writing project into a controlled algorithm handled nicely by a bot.

***

Andrea Avery (2022) published a stunning qualitative study of her writing course for high school seniors in Harvard Educational Review (Vol. 92, No 3), pp. 331-346) titled “A Face for My Autobiography: Lucy Grealy and Embodied Vulnerability.” She explains early that “the course is a fall semester memoir elective for high school seniors” (p.322):

“I ask my students to excavate areas of their lives that correspond thematically to the texts we study. For example, we start out reading Eggers’s (2000) memoir about caring for his younger brother after the untimely deaths of their parents, I ask students to excavate the theme of family” (p. 322).

The choice of family is perfect as an example of a still water theme for a senior year elective, running deep and wide, a reservoir of narratives, anecdotes, conversations, insights, reasons, funny stories, dreams. I wonder what might happen in a first or second grade writing community taking up family as theme for writing plays and poetry. Avery’s lead into her text engages us immediately by throwing her readers into the deep end of the pool, trying to shake us from the grip of the argumentative essay by making us hold a mirror up to ourselves:

“I take my place at the table with my students. Inspired by Ruth Ozeki’s The Face: A Time Code (2015), and in preparation for beginning Lucy Grealy’s Autobiography of a Face (1994), I have given every student a hand mirror. We spend the next thirty minutes silently looking at our faces and writing. We have our chintzy plastic hand mirrors, our pens and journals…” p. 321)

Later in the piece, after Avery provides a detailed sense of the readings she assigns, she explains how the course is structured and the nature of four required writing projects. One of the objectives of the course governing expected learning in reading and writing goes to genre knowledge, the greatest casualty of the Common Core. Avery facilitates her students’ self-understanding of a particular genre and also their shared understanding of substantive anchor texts within the genre. A great thing about going deep inside a genre if students have had little or no opportunities to do a genre study is their insight into the existence of genres as a thing. It’s hard to decide whether a genre study outcome falls in the “reading” or the “writing” rubric:

“At no point in the semester do I define memoir for them. Rather, students develop their own understanding of the genre by reading examples of it inside and outside of class. In addition to responding to each of the memoirs as literature via class discussions and written reading responses, students complete four themed autobiographical writing projects that I call excavations. Just as archaeologists grid sites and identify certain squares for excavation that seem likely to yield artifacts (Society for American Archaeology, n.d.), I ask my students to excavate areas of their lives that correspond thematically to the texts we study…” (p. 322).

Teachers interested in a setting for introducing AI as a writing tool would have a built-in force field around the urge to plagiarize. Bots can help out in many ways, but they cannot write a memoir. Avery indeed had experience with writing and publishing a memoir, experience which served her well in the course. This genre melds well with the professional development she had: “I am a proponent (and product) of the National Writing Project and its admonition that ‘writing teachers must write’ (National Writing Project & Nagin, 2006, 65). I believe that being a writer increases my credibility, if not my effectiveness, as a teacher of writing.”

In fields far from traditional boundaries of the typical writing course, Spork et. al. (2023) published an empirical study of the use of humor as an approach to teaching writing titled “When students write comedy scripts: humor as an experiential learning method in environmental education.” Including A well-developed literature review on humor as a teaching strategy, Spork et. al. (2023) point out that humor in education has been studied primarily as a teaching strategy with students as the audience. They turned the tables and taught learners an authentic craft-based set of genre principles for writing comedy scripts:

“The proposed method of using humor shifts the focus from the educator to the students, drawing on approaches that bridge a community of practice of comedy writing in the United States with environmental educators (see Boykoff and Osnes 2019). The method enables and empowers students to write their own comedy scripts on serious sustainable development topics. It was implemented in an elective course on Sustainable Development that is part of the two-year master’s program in Management at the Vienna University of Economics and Business” (p. 554).

***

Courses like the memoir elective and the comedy script framework could be graded on a piecemeal point system using a rigid calendar with inflexible due dates. Individual pieces of work could be collected and recorded in a grade book. Micromanaging and judging every part of a course-long writing project designed to provide opportunities for authentic engagement in a real-world genre, however, would likely backfire. Negotiated grading contracts with self-, peer-, and teacher assessments could form a map for formative assessment, and a portfolio scoring or exhibition could serve the purpose of summative assessment.

In alignment with theories of academic achievement motivation valuing students’ reflective analysis and goal-setting activities woven throughout the course, courses that stretch students in authentic directions in conjunction with socioculturally-based situated assessment of growth rather than decontextualized performance could evoke deeper changes in intrinsic motivation to write lifewide and lifelong.

Nancy Sommers, who contributed to the seminal body of research on writing as cognitive activity in the 1970s, studied the revision processes of freshman in college student writers contrasted with experienced adult writers and found that authentic experiences in writing indeed made a huge difference in how texts were shaped from rough drafts to finished text. She found that student writers in beginning undergraduate classroom settings revised their texts at the surface level, leaving deeper problems unresolved. Experienced writers reflected on their drafts to identify problems with meaning and then made deep changes where appropriate. Sommers interpreted this finding to indicate a profound pedagogical misunderstanding of revision:

“We tell our students: Be correct! Be concise! Be concrete! But above all: Discover! Yet we rob our students of this important part of the discovery process- this discovery of structure- by forcing them to write formulaic five paragraph essays. We impose rigid structures upon students at the risk of turning out terribly mechanical writing…for a fixed structure which often inhibits the discovery of ideas and, therefore, the process of significant revision” (Sommers, undated, likely 1980).

Reductive materialists in writing classrooms distort the meaning of “prewriting” as the earlier theorists thought about it. Prewriting often is a tightly controlled sequence of activities that yield ideas to write about for everyone in the class. Sommers discussed an element in the cognitive model of the prewriting process constructed by Flower and Hayes (1980) which did NOT make it into the popularized version of “prewriting.” The most important part of prewriting involves the student writer in making a strategic, goal-driven plan about what the writer intends the text to do and what options they have to fulfill their intentions—this work belongs to the writer, not the teacher.

Sommers saw a major link between “planning” and “revising” activities. Flower and Hayes insisted that before actual writing begins, real-world writers work for a firm sense of a hierarchical set of goals to guide them through the work. Sommers reasoned that without this set of goals, a writer has no basis for changing anything—if one has little idea of what they want the text to mean or do, they have no way to check to see if it actually does function and mean as they intend.

Richard Haswell, a well-published scholar and researcher in college writing assessment, is best known for his interest in growth over time as the proper focus of classroom writing assessment, particularly growth in metacognitive control of one’s writing process, including expertise in revision.

He studied undergraduates and found substantial growth among some writers. Syntax became more complex over time, he found, suggesting that experiences with revision at the nexus of syntax and meaning produces more highly developed syntactic expertise. Vocabulary became more sophisticated and discipline-specific as well, reaffirming the connection between disciplinary discourse experiences including reading, growth in writing, and disciplinary expertise. Like Sommers, he found that revision strategies evolved from surface-level edits to more substantive changes as writers developed more awareness of their writing process and could work methodically and purposefully in a self-regulated fashion.

A five-paragraph model of writing development in K12 in preparation for higher-education in the United States derives from a simple formalism which is very easy to teach, very easy to assess, and quite ineffective in preparing writers (cf: The Neglected R, 2003). First, in the earliest grades young writers learn to write sentences with capital letters and end marks. Over time they learn to string a few sentences together with a smattering of punctuation marks, and in third grade, they learn to write the Alexander Bain paragraph—topic sentence, three details, and a concluding sentence. By sixth grade they master the five-Bain-paragraph essay, and the remainder of their years in middle and secondary school develops their skills in writing argumentative Bain-based essays and nothing else.

Growth in sophistication as a writer depends heavily on reading, on creating cognitive maps or grids that organize personal interests leading downstream to topical expertise, and on intrinsic motivation, which expand as learners actively participate in academic discourse communities in classrooms or other social settings. Discovering one’s “interest territories” (Donald Graves) is crucial on the path to engaged literacy, properly the first order of business in first grade. Children who are thirsty for texts feed their interests and write and publish their thoughts and knowledge from first grade on, doing literacy in social worlds they build among peers (Ann Haas Dyson).

Haswell developed a useful strategy for measuring a writer’s growth over time based on comparing a piece of text written at the beginning of the course with a piece written at the end of the course. Here is his explanation of the procedure in a sort of laboratory setting:

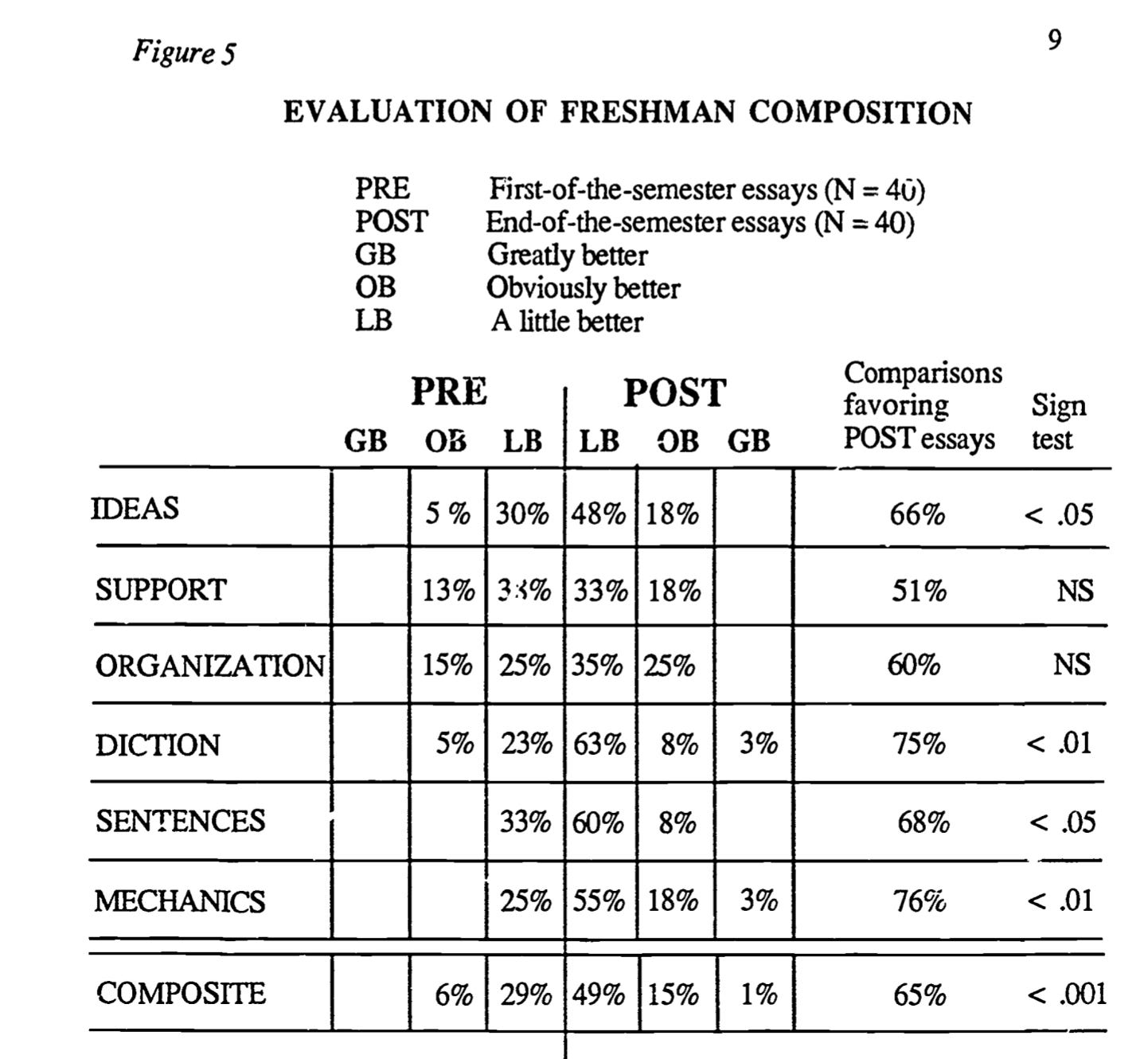

“The IPC [intra-person paired comparison method] evaluator rates essays in batches of two. The rater knows that each pair of essays was written by the same student, pre and post compositions written on switched topics, but does not know which is pre and which post. On the scoring sheet for each pair of essays (Figure 1, p. 4), then, will be recorded the rater's impressions not of one essay but of two essays. The rater’s first task is to compare the companion essays in terms of ideas or content…” (Haswell, 1988)1

Here is the score sheet Haswell devised to record judgments about which paper is better and by how much in a formal IPC session. I used this method as one tool in my dissertation which explored a yearlong portfolio project over the course of a year in a middle school. This method could be repurposed and reshaped or done informally as self-assessment, as peer-assessment as the basis for a reflective memo, as teacher assessment to discuss with stakeholders like the student and parents/guardians, etc.

The features raters look for could be voted on by local teachers or changed to fit the memoir genre or the comedy script genre or….. Whole portfolios created early and late in the year could be compared. The idea of examining earlier writing through the lens of writing produced after instruction regardless of the rater’s knowing which came first could be a key to starting up engines of growth in learner motivation in the hands of a well-trained (think: National Writing Project) teacher, in a way like comparing tree rings.

Mar 88

NOTE 22p.; Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the

Conference on College Composition and Communication

(39th, St. Louis, MO, March 17-19, 1988).

PUB TYPE Speeches/Conference Papers (150) -- Reports

Research /Technical (143)