The dissertation research cried out for mining, so rich were the data. I needed to publish during my first year of university teaching for purposes of tenure. The field record itself ran north of 1,000 pages single spaced stored in a five-inch binder full of observational notes from three middle school English classrooms across a school year, transcripts of interviews with teachers and students, reflective memos, and theoretical memos.

During the year of the portfolio experiment, 1994-1995, a tsunami of data each school day kept me working on the field record every evening, hour upon blissful hour. From this research I would publish a dissertation, a book, several book chapters, and several articles including a 1998 piece in Educational Assessment, which has been cited year after year in the literature on authentic assessment.

I’m basing this post on a small piece I published in a practitioner journal in 1998. Research in writing instruction at the time was compelling: Teachers who taught metacognitive awareness and looked for ongoing situated evidence helped novice writers over time increase their capacity to resolve problems of ever increasingly complexity during writing. The following sentence was written by yours truly in 1998 to open the article:

“Many writing teachers have long believed that helping students become aware of their writing processes is an integral part of the teaching of writing.”

Johnston (1983), for example, I wrote, suggested that teaching students to specify what they want to figure out with peers and teachers during conferences is just as important as teaching students the features of good products like effective organization: "If a strong pattern is established in the class so that the students dwell on discovering what is in their own and each other's writing,"wrote Johnston, "then the teacher can move on to help them look at how their writing might be improved" (75).

Camp (1992) suggested that students learn to reflect on single pieces of writing, and then on their writing processes and on collections of writings, through the use of reflective questions, such as these: "'What do you see as the special strengths of this paper?' and 'What do you notice when you look back at your earlier work?'" (72). As a way to develop awareness of process, Howard (1990) reported that she asked her students to choose one piece of writing that was satisfying and one piece that was not and then to reflect on how the two pieces differed.”

During the 1994-1995 portfolio experiment, students in the classes of three English teachers worked each trimester to produce their culminating portfolios of writing, including self-selected writing projects as well as assigned writings. Portfolios were exported from the classrooms to an examination committee of department teachers other than the teacher of record to grade: A-F. One question addressed by all students each trimester for the examination committee reads as follows:

“…[E]ach trimester students were given a ‘planning sheet’ with the following prompt included: ‘What has challenged you as a writer? How have you challenged yourself? How have you stretched your abilities as a writer?”

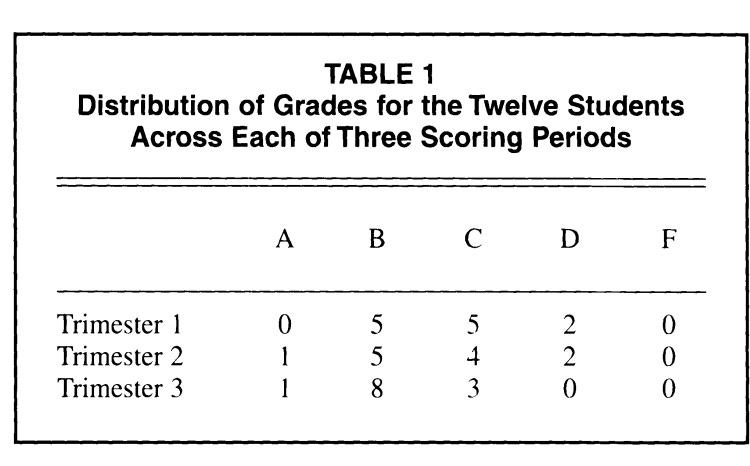

I selected 12 portfolios from across the three trimesters to analyze just for responses to this prompt. Four sets of three portfolios representing four students across the spectrum of trimester grades were chosen:

If you would like more information about how these grades were derived, please comment and I’ll respond to your question or issue.

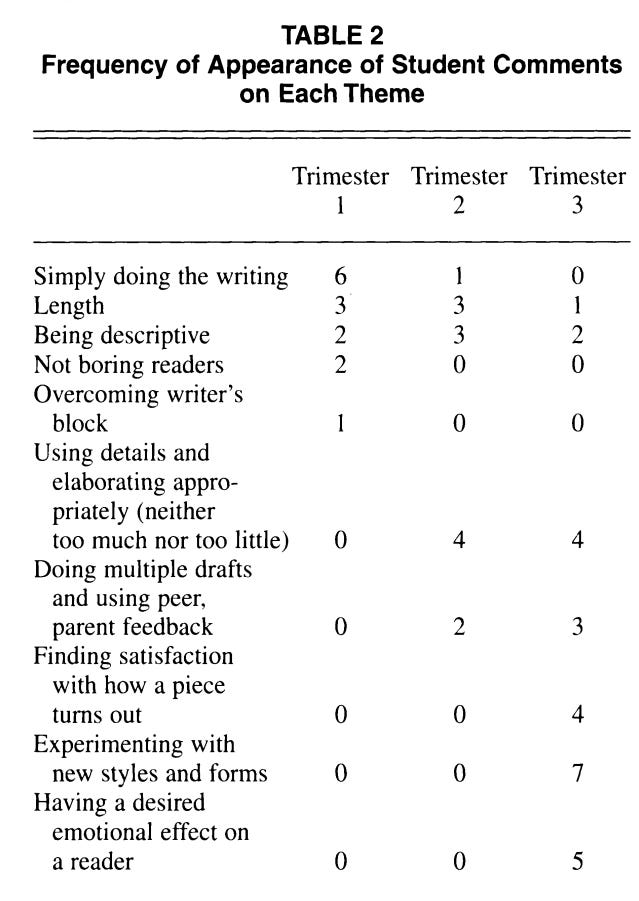

I analyzed the themes that emerged across the twelve portfolios. This table depicts those themes:

Of most interest to me was the evidence of increasing complexity in the range of challenges students identified:

I offer this study to you to encourage teachers to consider the role of writing self-assessments that position students as the experts in self-assessment who get better and better when a critical mindset is established and predictable reflective writing is produced and received as valued classroom work.

I appreciate your comment, Matt. I’m beginning to turn back without regret to the 1990s. For the longest time I wondered whether it was just me and my intense focus on authentic assessments that drew me back. Teachers were on fire with optimism. But I’m not just reliving the old days. There was something in the air. These data are poignant in my eyes.

Terry, I appreciate how you position student self-reflection as a central event in assessment for learning. Too often we mistake assessment as learning. But you have clearly differentiated these events. Thank you! -Matt