“A significant body of scholarship has highlighted the importance of improvisation in teaching, particularly the interactional and responsive creativity that is required for teachers to co-construct meaning with students. However, recent efforts inside and outside university-based teacher education have pushed against novice teacher learning through improvisation, preferring to focus on the ‘practicing’ of identifiable components or discrete techniques of teaching,” (Philip, 2019).

Philip (2019)1 discussed an emerging perspective on pedagogy which rattles the foundations of explicit, direct instruction. The quote above, excerpted from the article’s ‘background’ comment, is illustrative of the problem Philip identified not just in teacher education, but in teacher professional practice. Particularly in reading and writing pedagogy, the “best practices” mindset and the quest for a quick fix have penetrated the political sphere rendering the three-cueing system illegal in most states. Three-cueing mentoring is an improvisational strategy, not a scripted set of acts with accompanying assessments.

In theater and music, improvisation is a fundamental skill developed through reflective practice. In theater actors create in the moment using their body, their voice, their movement, every resource available to them to co-create a world on a stage. In the 1950s and 1960s legendary jazz guitarist Wes Montgomery, who played by ear, still thrills us with his in the moment magic. They make it look easy.

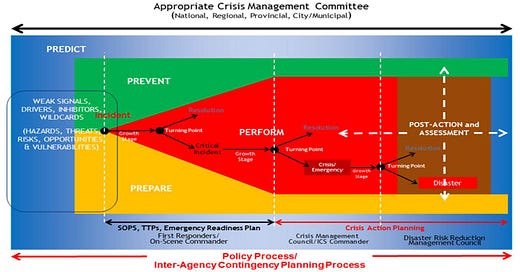

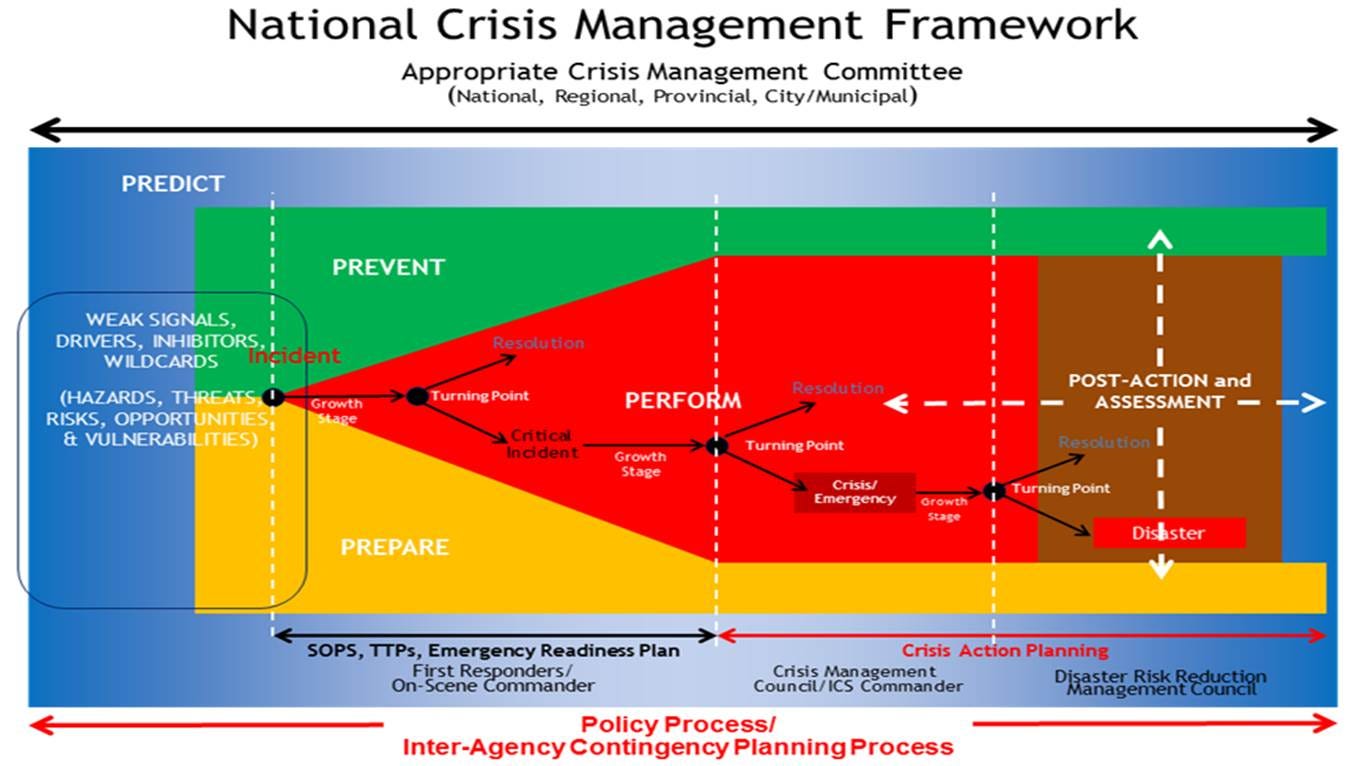

In high-pressure situations, the ability to improvise is crucial for effective problem-solving. Crisis managers have to think on their feet, adapt rapidly, and make decisions with limited information. This competence requires a combination of experience, creativity, and highly expert knowledge. In a way, teachers are preventive crisis managers—or at least they think of themselves that way. Missing an opportunity for a child to learn is a crisis; missing a step with a whole class of learners on the line is another disaster. Avoiding a crisis and managing those that happen—teachers are on the front lines.

*****

Philip (2019) used his qualitative analysis of preservice teachers undergoing preparation, aka novice teachers, specifically to practice teaching improvisationally, to inform his model of teaching. Fundamental aspects of the model cut across disciplines and developmental levels: responsiveness to students, critical reflection, addressing power dynamics, and connecting classroom learning to broader contexts. Indeed, a ground level skill fostered by experience is learning to listen to learners. Teachers who hear what is convenient or easy or seemingly irrelevant may continue with the lesson plan in blissful slumber almost as if following a script.

From my perspective, there are subject matter variations in Philip’s model which require ongoing research and professional development yet fall under the umbrella of improvisational pedagogy. STEM disciplines, for example, may focus more on connecting abstract concepts to real-world applications or emphasize interdisciplinary connections (e.g., math and physics) or explore issues of equity in STEM fields, but these teachers may not delve as deeply into social justice issues as humanities classes.

Humanities and Social Science disciplines could more easily incorporate discussions of power, race, and social justice, being responsive to the thoughts and feelings of the students in front of them. Teachers could connect current events and community issues to course content and thereby have more flexibility in the curriculum to allow for extended improvisational discussions. Nonetheless, the critical disposition and experience built by listening to learners as carefully as possible is in the bedrock of all pedagogy.

Some disciplines are ripe for improvisation. Arts and Physical Education might focus on embodied learning and expression, on cultural aspects of art or sports, or on issues of representation and identity in unique ways. The Embodied Physics project leverages dancers' kinesthetic knowledge to help students understand complex physics principles through bodily experiences. For example, teachers use imagery and metaphorical language during ballet classes to explain concepts like rotation and balance, saying things like "Remember to drill your foot into the floor in order to pirouette" or comparing a dancer's body to a pole during a spin.2

*****

Like great jazz musicians who use their ears, their instruments, their bodies, and their expertise to compose original melodic lines on the spot inside a tonal and harmonic universe drawn from deep knowledge of musical patterns and structures built over years and years of practicing and playing, great teachers emerge over time and experience if they are permitted to practice.

Philip (2019) unearthed serious resistance to the notion of giving preservice novice teachers training in improvisation. When he published and likely even more so today, political pressure has shifted the focus of teaching ever more toward deskilling, remote control, teacher-proofing what goes on in classrooms. The following summarize principles that Philip derived from his analysis of his preservice teachers who experienced his method.

Being attentive and responsive to students' needs, interests, and contributions in real-time is both a responsibility and a mindset. Teachers focused on steps in a lesson plan, under pressure to cover the day’s load of content, have competition for their attention, splitting their attention between student learning and teacher teaching, which are not always the same. Following students' lead, Philip’s second principle, grows from attentiveness to student interests and questions to guide the direction of learning while maintaining educational goals—not an easy task.

Facilitating students building on each other's ideas and encouraging collaborative learning and peer-to-peer idea development, in my view, could set the stage for ensemble improvisation. Teachers improvise on a theme in a discussion with group A; they then talk with group B and reveal some juicy details from group A. This chain continues at a fairly rapid pace until each small group is discussing their ideas in the context of a few juicy details from other groups, parlaying individual on individual build into group on group build.

Developing critical questions that promote deeper thinking and analysis, often related to issues of power and social processes, can be a matter of advanced preparation for an activity but doesn’t have to be. In literacy, for example, teaching learners how to interrogate a text using recognized methods (e.g., hermeneutics, deconstruction) inherently evoke critical questions. Teaching students to ask their own critical questions, to improvise themselves, is perhaps a hallmark of a teacher who has grown beyond direct, explicit instruction.

Addressing power dynamics—being aware of and actively working to address power imbalances in the classroom and broader social context—need not take up a lot of class time. Behaving democratically as an instructor and modeling the value of choice can have an impact on students’ schemas for good teaching and good citizenship. Insisting that everyone has a voice, that everyone listens to one another, and that ideas are always welcome whether they are right or wrong in the end promotes a student sense of entitlement to a voice in classroom matters.

Linking classroom learning to wider societal issues and students' lived experiences can become a way of thinking in the classroom. Although improvisational teachers are always on the lookout for local, national, and international news and events relevant to the lives of their learners, such teachers also can provide access for students to bring such issues to the attention of the class.

Engaging in ongoing reflection on teaching practices and their impacts is a large focus of the last sections of Philip’s article, well worth a read. Ensuring that improvisational teaching is guided by a commitment to social justice and equity as intense as a commitment to disciplinary learning is part of this activity of professional reflection. Understanding that every moment of teaching has political and ethical implications keeps teachers tuned in to their learners, listening and thinking deeply about what they are hearing—the heart of the professional work ethic.

Recognizing teaching as involving "wicked problems" that require constant re-solving rather than one-time solutions, Philip offers no panacea as those with toolkits, recipes, scripts, and binders offer. Place-relevant theory-building of teaching and learning tied to the specific context of instruction is an ongoing task of teachers with an in-the-moment, this-is-it disposition. Blindness or haphazard attention to the lives of learners can be defended in a script-oriented, prescribed practice paradigm. The importance of fidelity to the curriculum, the publisher, the administrator, takes precedence over advocating for the learner day in and day out.

Finding ways to be responsive and flexible while still ensuring that essential learning occurs—now that’s a tall order, one that demands privileging the human in being, one that takes skill, planning, strategy, disciplinary knowledge, and stamina. In this new age of AI, non-responsive teaching based on inflexible, detailed, sometimes dehumanized relations and interactions between teachers and learners enshrined in manuals and controlling lesson plan templates may in the end exacerbate the learning gap between the haves and the have-nots.

Philip, Thomas. “Principled Improvisation to Support Novice

Teacher Learning.” Teachers College Record (Volume 121, 060307), June 2019, 32 pages

https://www.terc.edu/embodied-learning-through-dance-and-physics/