The struggle between teachers and computers that began in the 1980s rages on today with pretty much the same root-level issue in play.

In everything I’ve read the past few years about AI in schools, including historical information about the early Apple in the Schools project, the teacher’s struggle is anchored in the paradox of change.

*****

Just a few days ago at a book club meeting of teachers, I heard much gnashing of teeth about young teachers nowadays. “They don’t know how to teach without computers. They are lost.”

Standard rebuttals like “Books and paper and pencils are ‘technology, too” fall on deaf ears. Books don’t have to be plugged in. But didn’t you read the book we’re discussing on a Kindle? A Kindle isn’t a computer…

Oh, well, I thought. This talk is purely emotional. Socrates himself would prefer hemlock over suffering the rage of this group. Klara and the Sun, Kazuo Ishikawa’s book recommended a few years back by President Obama, was a huge flop. Someone questioned Barack Obama’s credibility as a literary critic.

At one point there was a question about a minor point in the book. It wasn’t immediately clear what in the world is going on. Listening to the chatter, the full weight of the moment landed like a watermelon on my head.

“Google it,” someone said. “We can’t be the first to not get it.”

*****

In 1985, forty years ago, schools in America were in an agitated state a lot like they are today. I did a little time travel with Perplexity, and it all came rushing back in a flood of fragments and debris.

In 1985 science and math teacher shortages loomed as the lure of fatter paychecks in the private sector drew them from the classroom. “The overwhelming majority of the students tested had never heard of 'The Catcher in the Rye' or Don Quixote and could not identify Milton, Chaucer or Thoreau,” according to Patricia McCormick, UPI reporter. discussing NAEP scores.

Teacher shortages and dismay over how little knowledge students have are not new. In the age of AI, fears of teacher shortages still exist with another fear added on: teacher replacement.

A study revealed that in 1985 one-third of the nation's teachers reported being uncomfortable using computers. Mainstream computers at the time included the IBM PC and the Apple lineup of the “Fat Mac” with a 20MB external hard drive (I bought one—still have it) and the Apple II line.

Around that time I also bought a Hyundai: “The machine comes with 512,000 characters of memory, one floppy disk drive, a one-year warranty and the MS-DOS operating system used on IBM’s Personal Computer.” It sold for $699.00.

The threat of technology back then was felt not because of the awesome powers of the machine as we see today, but because an entity was coming between the teacher and complete control of the classroom. They started bringing these computer carts around to the classrooms and dropping them off for teachers to do something with.

*****

In 2025, many teachers have grown accustomed to using technology in their classrooms, especially following the rapid adoption of digital tools during the COVID-19 pandemic. But not all teachers see digital tools as “technology” or “computers.” The book club had several Kindle users who did not understand nor enjoy this artificial friend named Klara.

There has been a shift in mindset with teachers increasingly integrating technology into lesson plans to enhance student engagement and learning outcomes. However, surveys indicate that six in ten educators lack confidence in their ability to integrate digital tools into their teaching, particularly those over the age of 43.

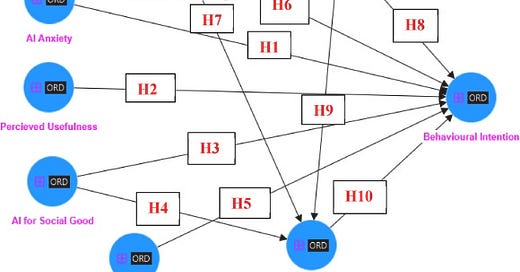

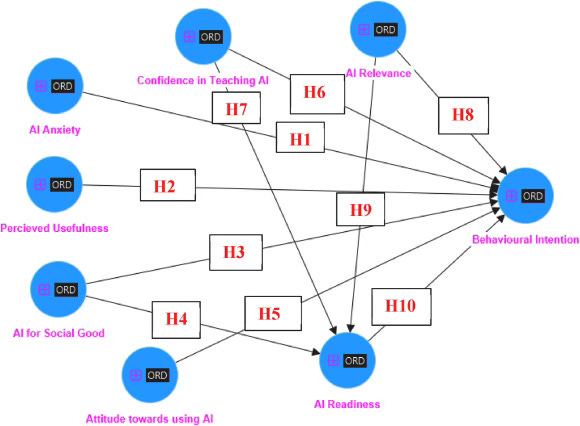

The issue of teacher acceptance of AI in the classroom is much more complex than other previous forms of technology. As a consequence, it’s much harder to give a number like “6 in 10.” A quantitative study of 385 teachers from K-12 published in 2022 theorized a cluster of aspects making up a teacher’s “attitude toward AI” exposing this complexity in the following figure:

In this study the authors focused less on “comfort” or “willingness” and more on “behavioral intention,” an approach of great interest to me. A “behavioral intention” is arguable well measured using quantitative techniques, but it also opens the door to qualitative research.

In my view, it is crucial to come to a phenomenological understanding of the experience lived by teachers struggling to engage at all with AI. Only then will instructional leaders have the knowledge base to work with them. Although there is a lot of talk from teachers, there is little listening with scientific ears.

*****

One thing I’ve learned about schools in the U.S. They are always, perpetually in a crisis. This constant drumbeat of conflict and chaos forced the political emergence of accountability measures that metastasized into NCLB and then CCSS. I want to spotlight more general likenesses between 1985 and 2025.

In 1985 minority college attendance was declining, with a 19.2% drop among students aged 19–24 between 1976 and 1983. There were concerns about equitable resources for schools and programs aimed at dropout prevention. In 2025 equity remains a central issue; concerns about dismantling civil rights protections in education under Donald Trump’s proposed federal policies are perhaps greater than ever.

Troubles with equal access to college in 1985 were social, political, and cultural. Segregated schools and tracking systems often placed low-income and minority students in vocational or general education tracks with weaker curricula, leaving them less prepared for college-level work. The so-called demographic cliff, i.e., declining numbers of high school graduates, raises questions about access and fairness in recruiting nontraditional or underserved student populations into higher education today.

Starting in 2025, colleges will face a steep drop in incoming freshman classes with projections estimating up to 600,000 fewer students over five years. This figure represents a 15-20% reduction in enrollment for many institution.

With fewer seats available in higher education classrooms, who will get to sit in them?

The paradox of change in education isn't really about technology at all. It’s about control and identity. When teachers resist computers, AI, or any new tool, they're often expressing a deeper anxiety about their changing role in the classroom.

The book club oozed this tension: The same teachers who reject AI as too threatening readily use Kindles and Google searches when it serves their needs.

This selective acceptance of technology reveals that the core issue isn't the tools themselves, but rather what they represent: a shift in the traditional power dynamic between teacher and student, between knowledge-holder and knowledge-seeker.

Just as the teachers of 1985 weren't really fighting against Apple IIs, today's educators aren't truly battling ChatGPT. They're grappling with fundamental questions about their purpose and value in an evolving educational landscape.

Perhaps the most important lesson from four decades of this struggle is that teaching has never been about controlling information flow. Teaching has always been about guiding students through the process of learning. Whether that guidance happens under a leafy tree or in a AI-enhanced classroom matters far less than our willingness to embrace our evolving role as educators.

Crisis in American education isn't new, and it isn't primarily technological. It's a crisis of adaptation, equity, and identity that has persisted through every era of educational change.

As we move forward, the real challenge isn't choosing between tradition and technology, but finding ways to honor the timeless aspects of teaching while embracing new tools that can help us better serve all students.