Help Wanted: A New Metaphor for Schools

The factory model of schools we inherited from the early 20th century is still America’s default metaphor, perhaps in different ways depending on geography. Administered primarily at the state level with federal laws and funding on the line, K-12 school cultures and practices vary. Schooling in Kentucky, where underserved rural communities in 1990 were justicially required to reform,1 differs from schooling in Alaska2.

But the factory metaphor infrastructure is stable and durable: subject matter frameworks organized by grade level, teachers organized by credentials and degrees, students organized by age and ability. People are objectified, and students are seen as little adults in competition for academic capital.

*

We shall see how well the factory metaphor holds up after the COVID era. Management was not well prepared for the corona virus. Even real factories, the tenor of the vehicle of the factory metaphor, had to shut down.

We learned a few things. We learned the many blessings of face-to-face teaching, especially for early readers, especially for social and emotional learning. Many educators based on what they saw have newfound confidence that they are truly needed, although today’s headlines trumpeted a massive teacher shortage of national scope.

Journalists report anecdotal evidence that this shortage resulted from shortcomings in the factory administration of the workplace and abuse from parents upset about loss of daycare for their offspring.

There is no Division of Qualitative Research, no army of ethnographers, in public health nor in educational administration. The problems of factory model management multiplied during the viral disruption in part because no one could discern a phenomenology of teacher-parent-child experiences during school stoppage and had few effective strategies to mitigate the damages.

*

Besides the flawed premise that children are formless raw material or stalks of corn amenable to physical science methods, political turbulence rattled public confidence in science as a source of policy in any sphere. Evangelicals fueled the fire by distinguishing between ‘scientism’ and ‘science.’

The ‘ism’ is intended to add an ironic element of worship to science believers, to make my faith in my doctor a blind and stupid faith in science, to portray respect for science as a superficial commitment to believe whatever scientists say. Quite a semantic burden for a three-letter suffix.

*

American schools as factories, managed by data, are tasked with producing adults ready to function in the economy and to be governed by powers located in capitals. Schools are not Maslowian community centers concerned with inner life and meaning to help young people mature into self-actualized, ethical, responsible adults who participate in their own government.

These are hardly idle notions for anyone interested in teaching children to occupy positions of self-advocacy in the face of ideological hostility. Training a person to become a subject, to occupy an oppressed status, entails repetitive institutional experience in following arbitrary directions without question.

Christine Sleeter (2015)3 published a paper calling for a counter theory of the purpose of schooling, a framework rooted in historical fact, to stand in opposition on the policy stage to the unjust symbolic and bodily violence of the autonomous, mechanical, hierarchical, factory model of schooling:

Sleeter (2015) pointed to mixed-method research to counter the sinister view that schools work. Work for whom?

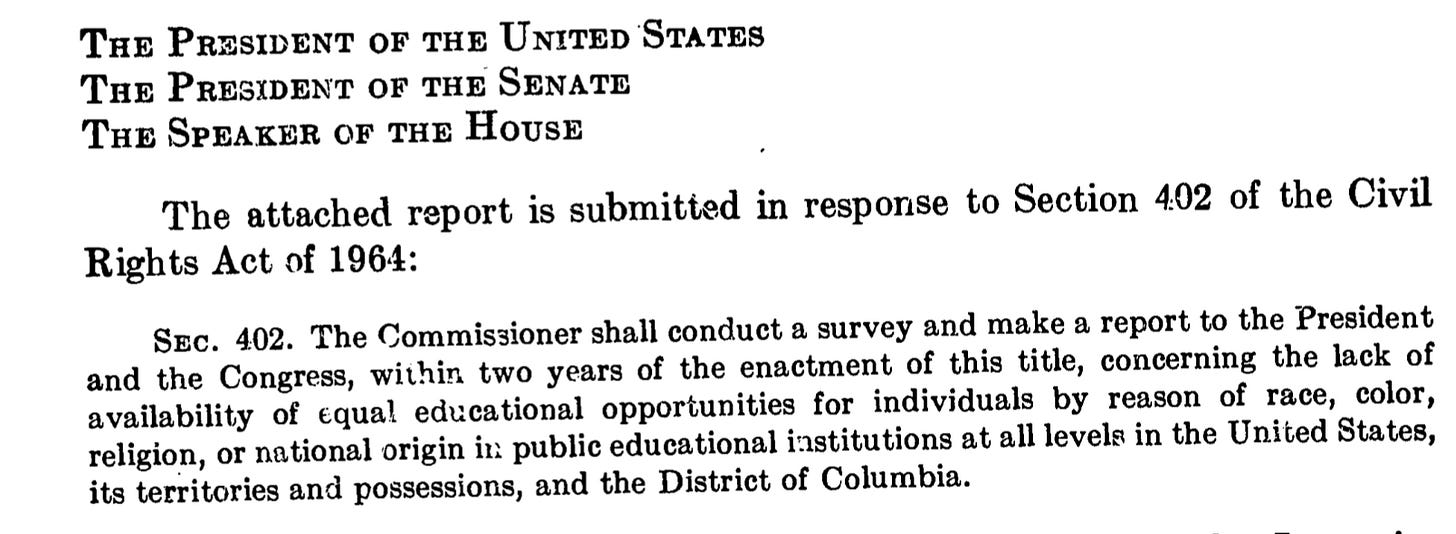

In fact, pointing to a theory of multicultural education grounded in research has a precedent in American educational policy making:

What, specifically, was the Commissioner being asked to find out?

This policy resulted in the Coleman Report (1965)4 , a landmark study revealing widespread and ugly inequalities inviting studies like Oakes (1985). Recent political action to legalize the whitewashing of schooling in states like Florida and Texas by forbidding lessons in America’s overwhelming legacy of racism and its active presence today seeks to white out the Coleman Report.

*

The call for grounding school management in an ethical mission is cross curricular. Dennie Palmer Wolf5 wrote about the recent work of international art educators advocating ‘socially just assessment,’6 an idea that implicates basic quantitative science in management’s standardized focus on grading systems, test scores, and judgments of quality in unfair and biased art education.

*

Sleeter’s (2015) call to replace scientific management with emancipatory research appears to be slowly happening. In the field of reading, a panel of well-published and respected experts with deep knowledge of the current state of the Science of Reading (SoR) presented at a Literacy Research Conference in 20207 in an effort to explore a “wide-angle view of research” to embrace a paradigm of qualitative methods complementary to SoR.

I read the document summarizing the panel discussion as raising two core questions: How do we transition research in reading education from overrelying on quantitative science to an embrace of mixed-methods research? How do we separate technical aspects of literacy that can be counted and statistically analyzed from sociocultural aspects that must be situated and contextualized?

As Brian Street argued in the 1980s, an autonomous view of reading, that is, a single lens on reading as an automated and technical process amenable to reliable and valid measurements, wrenches literacy from history and culture and distorts its nature as human behavior in society.

One presenter on the panel, Sonia Cabell8, spoke about quantitative research on the effects of variability in prior knowledge on measured outcomes of reading events. Clearly, schema theory and its supporting experimental studies have demonstrated that a reader with strong prior knowledge brought to the act of reading a passage about that content will end with a better performance than a reader with impoverished prior knowledge.

At issue here for Cabell, however, is the reality not discussed in the basic science that knowledge is the unambiguous, privileged goal of reading activity amenable to testing and grading across all spans of formal education. Knowledge counts a lot. Prior knowledge, however, seems to count less even though it is central to making a high grade on a comprehension test.

As we know from the mixed-methods research on vocabulary growth in early childhood done by Hart and Risley (1995) in their book Meaningful Differences, toddlers of poverty vs. those of affluence experience radically different apprenticeships in learning to speak and listen. Affluent parents provide their children rich opportunities to talk, get meaningful feedback and guidance, and experience responsiveness. Non-affluent toddlers hear far fewer words, encounter less variety of words, and do not get a lot of substantive response.

Hence, opportunities to learn to use language discursively and cognitively to explore interactions with the world that produce knowledge are more frequent and impactful in affluent homes. The ‘haves’ come to school with memories organized in structures and indexed with words, and speaking experiences that afford channels of participation in whatever teachers do to activate knowledge (memories) prior to reading. The have-nots truly have less in their memories to begin building what Donald Graves called a ‘territory of interest,’ an epistemological homestead on the frontier of schooling.

What metaphor of school management would capture equity and justice in managing a prior knowledge curriculum built on epistemological fairness for all? “The self-proclaimed professor’s tongue too serious to fool shouted out that liberty is just equality in school” sings Bob Dylan (1965) in ‘My Back Pages.’ As Dylan knew, equality is easy to say (“Equality… I spoke the words as if a wedding vow”) but hard to fulfill.

*

Socrates, the man who was sentenced to death twenty-five centuries ago partly for corrupting young Athenians by luring them into thinking critically about their lives, single-handedly laid the foundation for every major Greek philosopher who came after him including Plato and Aristotle—without writing a word. He mistrusted writing as an instructional tool.

He had been gobsmacked years earlier when a friend revealed the answer the Oracle of Delphi gave him to his question ‘Who among us is the wisest?’ Why, that would be Socrates, quoth the Oracle.

‘My my,’ Socrates must have thought. ‘We are in trouble if I’m at the top of the heap.’ So he set out on a career challenging Athenian thought leaders and politicians during public speech acts in ways displeasing to the powerful.

He bucked the hierarchy. He found no wise candidates to replace him as the wisest, but he refused to stop looking, leading to his cup of hemlock for the crime of impiety—failure to follow the party line when it came to the supremacy of supernatural forces in day to day life.

Plato wrote a series of dialogues where his teacher, Socrates, speaks with students about epistemology, ethical reasoning, and morality. The following excerpt from the Phaedrus (Phdr. 275a-b) finds Socrates talking with young Phaedrus, who has been smitten with the technology of writing and is working on a draft of a speech to read. “And now you” is Socrates speaking to Phaedrus:

Early childhood memories are made from the fabric of raw experience in a surround of spoken language and face-to-face interactions. Parents have no trust in writing. Memory in early childhood is built from experience and spoken dialogue.

Those affluent parents in Hart and Risley’s study who frequently and formally supported their children’s use of language to build knowledge/memory did not trust in writing to remind children, but in children’s legitimate participation in family experiences as important members who listen, speak, respond, question, and are responded to. Their children come to school with something in their minds to activate. Words remind them of what they know.

On the first day of kindergarten affluent children are ahead in the race to the top not because they can read and write, but because they have memories stitched together in patterns of language, ready to learn to decode print sensibly. Plato could write about Socrates because Plato’s apprenticeship with Socrates involved face-to-face interaction producing memories.

*

Pressure is mounting for justice in school, not merely equality of opportunity. Providing buildings, clean restrooms, teachers, desks, computers, and textbooks to all children is necessary, a fitting task for factory management.

But the grand mission in literacy education of preparing minds to use language in the service of cognitive and epistemological growth requires justice and fairness. Quantitative science will ultimately contribute to the solution, but it will be just a part. Its dominance now as both a school management strategy and the gold standard for pedagogy is a problem.

David Pearson, who has helped shaped thinking in reading research since his early days as an editor of Reading Research Quarterly in the 1970s, a powerful mixed-method scientist himself with years of wide-angle participation, served as discussant for the panel searching for a “wide angle view on research” and offered a template for a full complementary portfolio of research methodologies.

For example, David distinguished between basic experimental science that produced knowledge about decoding and fluency, the acknowledged domain of SoR (the Science of Reading), and ethnographic research illuminating the situated and ideological nature of reading pedagogy. How we look into schooling holds promise for changing what we see.

Scientific management deploying a full complementary portfolio of scientific methodologies, including both objective and subjective methodologies, in the Office of Human Learning stands a chance of uprooting the autonomous factory model by holding up a mirror to its callous and dehumanizing features even as it indexes what systematic and quantitative protocols are appropriately managed by looking at numbers.

https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/2020/04/11/kera-30-how-did-kentucky-education-reform-act-hold-up/4870847002/

https://alaskais.com/the-educational-system-of-alaska.htm

https://www.fau.edu/education/faculty/docs/2015-multicultural-education-vs-factory-model-schooling.pdf

https://hub.jhu.edu/magazine/2016/winter/coleman-report-public-education/

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED604372.pdf

https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED604372.pdf

DOI: 10.1177/23813377211032195

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353464962