The idea of teaching students to read closely, to hold them accountable for the brute signifiers of the text, is tantalizing. Having spent a good portion of my early adulthood as an English major, I thoroughly enjoyed putting Moby Dick under a microscope, annotating even the footnotes. (In eighth grade I loved diagramming sentences.)

Still, I remember walking back to my apartment the last night of the last class of my last semester in a Masters degree program, not regretting what I had done, but deciding that advanced graduate work in literature was not for me. Although I had learned to write papers of literary criticism, I had forgotten how to read the books that had opened my eyes to the mysteries in high school and community college.

In a world where power is knowledge—oops, excuse me, knowledge is power—one could argue that an instructional culture which privileges close attention to small details of complex texts is egalitarian and progressive, preparation for college or career. Read on, dear reader, read closely. Not everyone agrees with David Coleman’s argument embedded in the Common Core, though in its decade of penetration into schooling it has gone deep (see upcoming digital artifacts). For example, a dissenter even before the Age of Coleman, Mackey (1997) researched “good-enough” reading and discovered that literary readers need the freedom to use their time during acts of reading to balance internal competing demands on consciousness. Witness1

“[R]eaders demonstrated the need for provisional understandings, the ability to take note and move on, the role of affective substitution, and the reading through and against misunderstandings. Reading is an event in time: complex, untidy, and inevitably partial. Often when reading researchers talk about reading they inadvertently or otherwise camouflage the inherent messiness of readers' temporal accommodations to a text by referring to post-reading responses.”

Indeed, camouflage is an apt metaphor for the effect of research that uses post-reading responses alone, especially results from text-based Q and A, to support inferences about during-reading behavior. In all of the shibboleths of close reading, the one non-negotiable is the Q and A after reading, the post-reading response. Weak responses indicate that whatever was going on was wrong. But what if it wasn’t wrong? What if it was actually right?

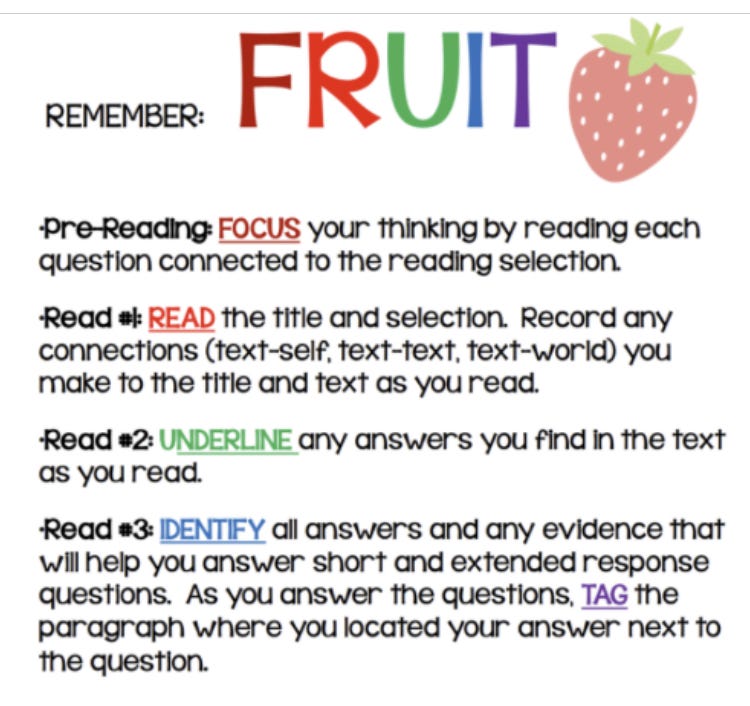

Implicit in “temporal accommodations” is the notion that readers have intention and do self-monitoring, two elements that readers functioning in a close reading instructional context cede to the teacher, who defines both the accommodation and the intention. “The inherent messiness” of reading is tough enough to wade through when unencumbered with external mandates inside complex text, all but impossible to clean up on remote control from the outside. Indeed, if by “close reading,” we mean teaching kids to do the “cleaning up” spic and span as they read, we may be on a fool’s mission. Still, we try:

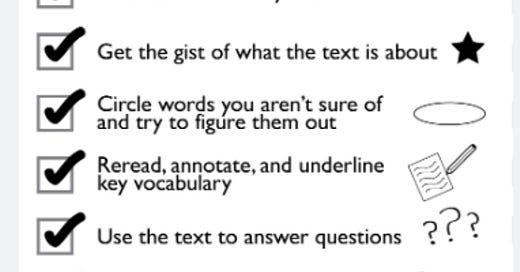

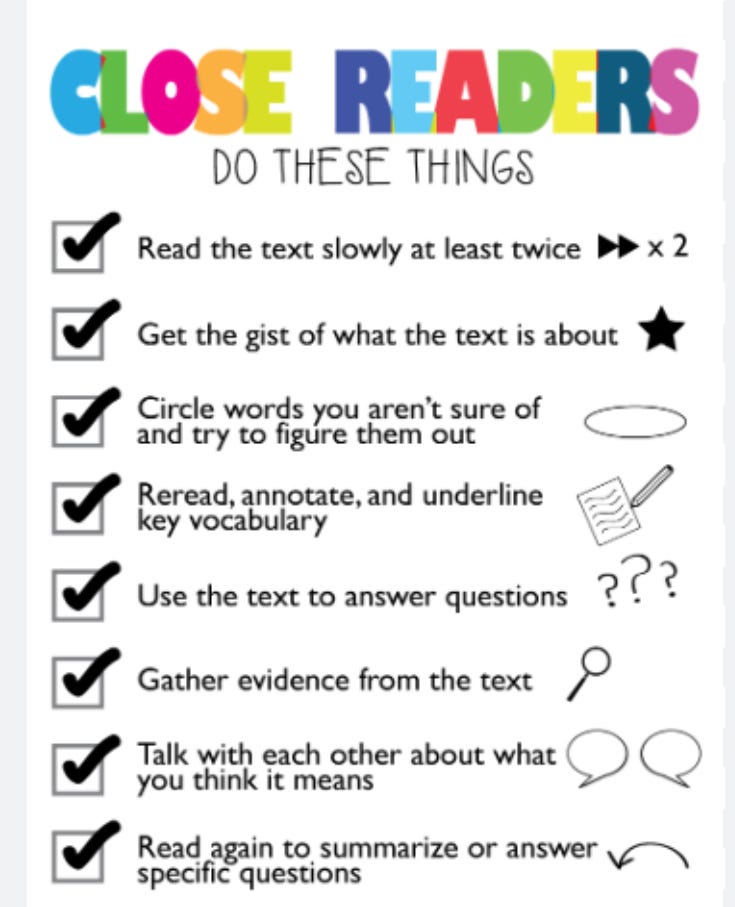

I sense a desperation in this poster, an overkill. Read slowly, you tell me, thinks the student—at least twice. Reread, you tell me, again. Circle words, underline words, annotate words, you tell me. Use the text, gather evidence from the text, read again, summarize, answer questions, summarize, Samuel Coleridge’s slave in a diamond mine. I find myself walking to my apartment on the last night of my last graduate class in literature again…

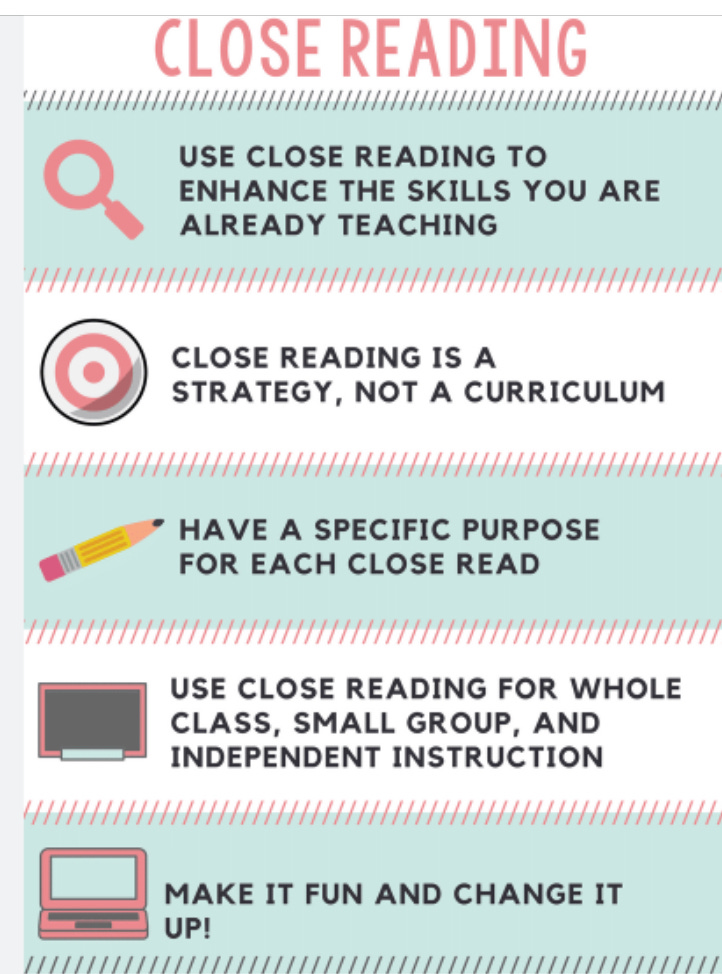

We tell teachers—

Make it fun? Change it up? What does that even mean? Can my specific purpose BE to teach kids to have fun while doing the serious work of reading? “Use close reading,” the poster says, addressing me as a teacher. Close reading is a teaching strategy, not a reading strategy. Use it to teach skills, use it all the time, whole class, small group, but make it fun, change it up? Have a specific purpose for each close read. What about the students? Is my purpose my modus ponens their purpose? Hmm… I thought my purpose was to teach close reading? Am I reading this poster to closely? Did I just write “to” for “too?” Wait, may I take a time out to reflect on my provisional understanding? Do I dare eat a peach?

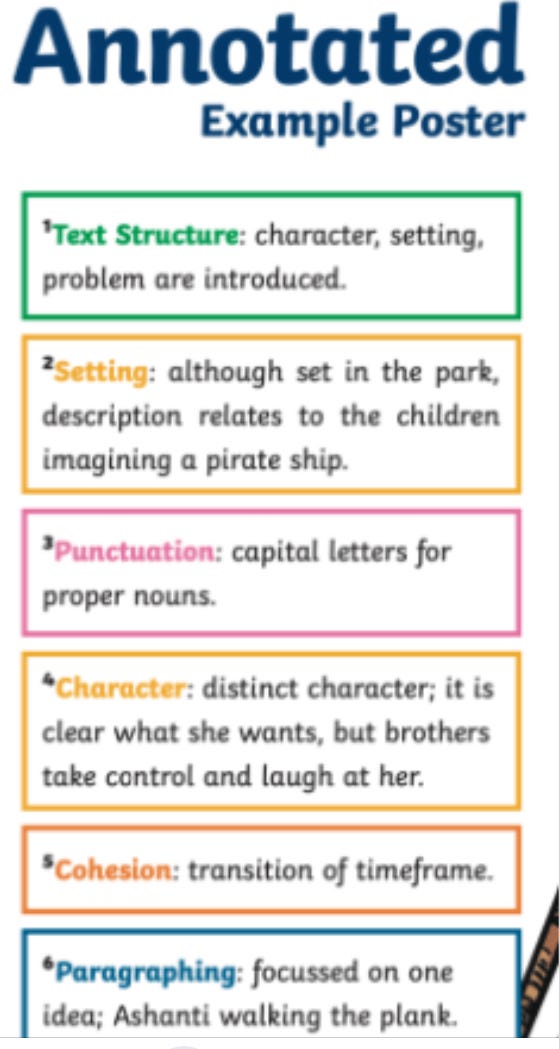

Not yet, dear reader. I hope you have been annotating this post. It’s so easy to do on a screen. They give us those bright colors—makes you think all the world’s a sunny day.

Color coding overlays a map of the textual territory which may or may not help me balance my provisional understanding with my accountability to the text on my journey to good-enough understanding, but it will make me attend to text structure, punctuation, and story grammar. I need a snack about now.

https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Good-Enough-Reading%3A-Momentum-and-Accuracy-in-the-Mackey/3075d977c6e346b0330131b3b11971fbcc841c01