“The degree of fusion [emphasis added], that is, the strength of association between an activity and its outcome, varies… [as]… does intrinsic motivation. Activities…strongly associated with their goal are more intrinsically motivated than activities…weakly associated with their goal. …[A]s much as reading this {post} article {the activity} is hopefully (sic) associated with satisfying curiosity, …another [reading] activity… [may be]… more closely associated with satisfying curiosity and hence, more intrinsically motivated” (Wooley & Fishback, 2018).

So I appreciate your voluntary eyes on this post. The fact that nobody told you to read it, that you are not responsible for being tested on it, suggests that you are willing to invest effort to find something of interest to you in these words. Who knows? And I’d better get to it right quick eh?

Wooley and Fishback (2018) assumed one goal associated with reading activity vis a vis their article: the drive to find out, to slake one’s curiosity about academic motivation—but my gut tells me you aren’t reading here just out of curiosity, at least not a specific curiosity as in a search topic in a database, or if you are and you’ve been reading my posts from time to time, I don’t constrain my posts thematically, theoretically, generically, etc. My posts go all over the universe of discourse—anywhere we find literacy.

As near as I can tell at least from Substack, many educated people are reading deeply and widely for insights into the craziness of the world these days. In the field of reading alone—a small speck of dust in the galaxy of disciplines which may already have become invisible—mission creep across disciplinary lines from anthropology to cognitive neuroscience has shifted *reading* from cultural activity to phonological activity to emotional activity to neurological activity.

It’s the activity, stupid (paraphrasing James Carville, 2024). It’s the satisfaction, to use the psychologists’ term, sometimes the elation, of stumbling onto a vibrant, awesome moment that turns the kaleidoscope a little, a touch, colored shards of glass tumbling into space.

3e-ness. Embodied. Let me relax and engage. Embedded. Let me grasp my surround. Enacted. Let me do this in my own way at my own pace. Brain autonomy. Time slows down. Of course, the most prized of these moments are those that render the individual more competent, more capable, more skilled, more aware, wiser going forward. We seek out these moments.

We take up the pleasures and the pains of challenges, we look for them, we struggle to understand meanings, we carefully set core vocabulary in slotted thrones in long term memory and rollup our sleeves to get technical—and we love it because we sense improvement, growth, we feel our powers build. This intrinsic motivation is future-oriented, goal-oriented, principled. Plus it’s fun.

A powerful, more primitive drive makes me play classic rock at farmers markets. I don’t do it to improve myself so much, though I do pay attention to what I learn from improvisation to make the songs better. I don’t do it to make money so much, but I need to justify the cash outlay for equipment and related costs. Music and market is a fusion of a) feelings evoked from listening to and performing music from my younger days and b) families buying vegetables and fruits in the open air.

Fusion.

At its core, fusion represents the merging of distinct elements into a unified whole in a synergy that transforms the original elements into something new, something greater than the sum of the parts. In physics during fusion, energy is released to accomplish a transformation. In the early universe, about 3 minutes after the Big Bang, conditions allowed for the fusion of protons and neutrons to form the first atomic nuclei. The idea that “conditions” had to “allow for” fusion to synthesize atomic particles suggests that fusion is finicky. Here we need to begin to think about conditions in classrooms that “allow for” fusion.

Natural fusion occurs in the core of our Sun. Hydrogen nuclei fuse to form helium, releasing energy in the process. Stellar fusion similar to the Sun takes place on other stars depending on their mass and stage of life. Thermonuclear weapons like hydrogen bombs, unfortunately an accomplishment of destruction, use the principle of nuclear fusion. Sushi burritos, cronuts, jeggings, skorts—there is no shortage of culinary, musical, architectural, or fashion fusions when we gravitate from war to peace.

*****

Fusion is an apt term to serve as a unit of measurement to parse intervals of intrinsic intensity learners might experience in the embodiment, the embeddedness, and the enactment of disciplined academic work in moments of assigned activity from the early grades to the most advanced levels of education. One student may be bored to tears; another may be riveted to the work.

Traditionally, teachers have been trained to stimulate motivation aka “interest” or “purpose” at the beginning of an activity. “Interest” is ambiguous; here it means curious, there it means investment. I would substitute “stimulate” with “explore.” How we speak with learners is rich with motivational cues.

—[fiction] Let’s “explore” your interest in the anatomy of the human hand. Any musicians in this room? Catherine, I know you play piano. Arturo, I’ve heard you play your guitar. Who else? Oh, great! Lots of musicians. So let’s take a look at your hands. Just for convenience, let’s take the right hand. Let me ask you this first: If you have some malformation of a hand you don’t want to put on exhibit, by all means, don’t do this. OK? What are the movements of your hands?—

Teachers also are trained to state the learning objectives, describe the expected work products clearly, explain how students will be evaluated. These issues are among the most difficult acts of teaching. Students commonly fail to understand what the expectations are for them. If they do, they find a teacher-prescribed sequence of micro-activities designed to prove that they completed the work. Often, when they are assigned a reading, they don’t know how much or what or to what degree of detail they should aim; when they show up to class, the teacher will usually tell them what they should have read anyway.

The most dangerous flaw in lesson design and implementation from the perspective of intrinsic motive advocacy happens when teachers use the test as a proxy for the reason to engage in the work. Similar controls diminish self-determination and regulation among learners when teachers say things like “This will be on the test.” Learners who are authentically engaged and participating in epistemological work develop stronger drives to grasp interconnections among ideas than are learners on a scavenger hunt for what might be on the test.

Unfortunately, I know of nothing in the mainstream of preparation nor professional development that trains teachers to reason about the relationship between intrinsic motivation and exertion of effort to achieve the goal of every lesson. When a teacher sets out to plan learning activities in pursuance of a learning outcome, given a two-three week unit of instruction, these activities usually link to a theme, a topic, a module, something to build or crescendo to a culminating point. Built in assessments are enacted to help students self-regulate their learning strategies and to clarify expectations for learning. Expected competence in both content and level are made clear through rubrics, models, Q and A, etc.

Despite the most elegantly designed units, assigned activity in which a learner is bored, passive, thinking superficially, trying to get it over with, is disembodied (involuntarily constrained in a setting), non-embedded (doing self-defined non-important things for purposes of compliance) and under-enacted (working half-heartedly to avoid punishment) would get a low fusion score regardless of qualities of a competence or achievement score. Motivation is completely extrinsic in this case. The learner may have achieved the teacher’s objective as measured by the test with little concern for the development of a dislike for the activity within the discipline.

The problem, of course, is such experiences dehumanize learners by putting them in sociocultural settings with a disregard for academic motivation as a learning outcome. Psychologists have long discussed “pawn theory.” The product of the activity usually stands in as a proxy for achievement and nobody really cares about what the learner has been taught to expect from future activities. Little Albert learned to cry when he was presented with a white rabbit or a Santa Clause mask. Little children may learn to cringe when they are called to a phonics activity carried out with no apprenticeship purpose other than to follow instructions.

The term “perceived locus of causality” (PLC) was coined in the 1950s, raising the issue of agency/actor in a positivist theoretical paradigm. Today, of course, agency is a highly nuanced sociocultural concept. DeCharms (1968) picked up on this concept and ran with it, ultimately uncovering the ‘internalized mechanism’ which is constructed in the consciousness of a learner in an environment of relentless external control vs an environment that fosters autonomy.

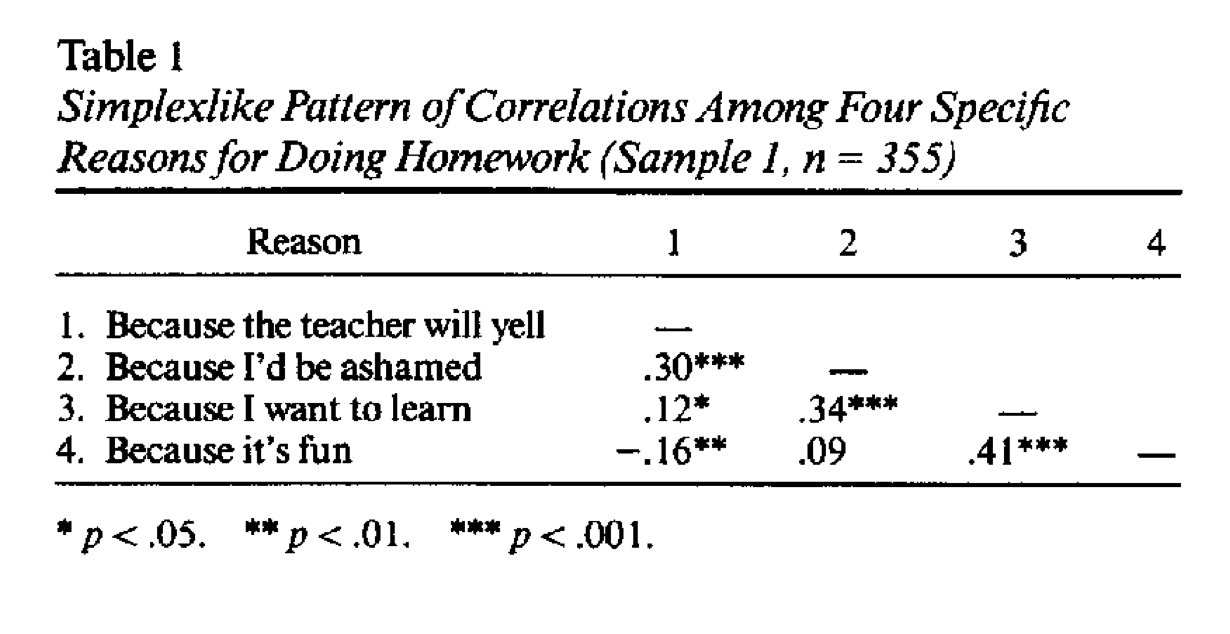

Ryan and Connell (1989) articulated complexities in this notion in ways that are more helpful to teachers, particularly with their demonstration that casual observations can help teachers grasp the motivations of their students. In this case, the researchers interviewed 355 students regarding their PLC (perceived locus of causation) for homework and discovered that those who exert effort for external causes like avoiding teacher’s chewing them out aren’t among those who do so because they happen to want to learn. I’ll present a table first and then unpack it:

In its basic form, the message of this table is simple. Children who do their homework because they fear getting yelled at by their teacher (lack of autonomy and self-determination) are not the same as children who do their homework because they want to learn (autonomy and agency).

Central statistical facts from the table are as follows:

a) "Because the teacher will yell" has a moderate positive correlation (.30) with "Because I'd be ashamed" (p < .001), a weak positive correlation (.12) with "Because I want to learn" (p < .05), and an even weaker correlation (-.16) with "Because it's fun" (p < .01). Teacher exerting authoritative control is the actionable cause of homework completion, roughly a third in order to avoid shame, with little evidence of an intention to learn and negative evidence of having fun.

b) "Because I'd be ashamed" has a moderate positive correlation (.34) with “because I want to learn” (p < .001) and a weaker correlation (.09) with "Because it’s fun" (p < .001).

c) "Because I want to learn" has a strong positive correlation (.41) with "Because it's fun" (p < .001).

External motivations (fear of teacher yelling, shame) are positively correlated, suggesting students who fear negative consequences also feel shame about not doing homework. There's a positive relationship between wanting to learn and finding homework fun, indicating intrinsic motivation factors are linked. Fear of the teacher yelling is negatively correlated with finding homework fun, suggesting external pressure may reduce enjoyment. Interestingly, shame is positively correlated with wanting to learn, which might indicate internalized pressure—not wanting to let someone down—leading to a desire for academic achievement. The strongest correlation is between wanting to learn and finding homework fun, highlighting the importance of intrinsic motivation.

*****

Deci et al. (2004) studied the question of differences in intrinsic motivation in relation to the content of one’s goals: “…[P]ursuing goals with strongly salient extrinsic content (e.g., wealth, image, and fame) tends to be associated with poorer mental health than does pursuing goals with strongly salient intrinsic content (e.g., relationships, growth, community, and health),” they wrote. The examples of human values and interactions as inherently intrinsic in content is important for teachers who want to bring peer collaboration into the core of classroom activities.

Deci et al. (2004) continued to caution against socializing children in a controlled autonomy society. “…[W]hen the importance individuals place on extrinsic goals is high…, these individuals …experience (a) less psychological well-being, as indexed by vitality, self-actualization, and self-esteem; (b) more psychological ill-being, as indexed by depression, anxiety, and narcissism; (c) greater likelihood of high-risk behaviors such as tobacco use; and (d) more conflicted relationships with friends and lovers (e.g., Kasser & Ryan, 2001; McHoskey, 1999; Ryan et al., 1999; Schmuck, Kasser, & Ryan, 2000; Sheldon & Kasser, 1995; Williams, Cox, Hedberg, & Deci, 2000).”

*

Fusion.

At its core, fusion represents the merging of distinct elements into a unified whole in a synergy that transforms the original elements into something new, something greater than the sum of the parts. The motive of the learner, when it is real and as powerful as human motives can get, rivets the learner’s attention, organizes thinking, relies on reasoning, is emotionally metacognitive, feels suspense, and drives persistent engagement with the subject matter.

It fuels curiosity and exploration, enhances information retention and recall, promotes meaningful connections among concepts, encourages creative problem-solving, fosters resilience in the face of challenges, cultivates a growth mindset and self-efficacy, stimulates critical thinking and analytical skills, inspires self-directed learning and inquiry beyond formal instruction, generates a sense of personal investment learning, and shuttles academic knowledge to real-world applications.

Changing learning from a passive activity into an active, dynamic mindset where the learner becomes fully immersed in the pursuit of knowledge and understanding creates a state of flow where time seems to fly and the learner finds joy and fulfillment in the act of learning itself. This level of motivation not only enhances academic performance but also contributes to personal growth and lifelong learning habits.

The need to have adults proud of you (the student) is an important motivating factor as well. I think of it as in between the motivations you describe, as it is a natural feeling to be proud of yourself and then want to get that positive reaction from the adults you love and/or trust most. In the classroom, teachers build relationships in part by sharing casual, positive feedback ("You worked hard. I see you.). That is a powerful motivational tool for students and, from my perspective, helps solidify the intrinsic motivation necessary long-term. Love the article, Terry.