Balancing writing instruction

Balance is slippery when it comes to literacy instruction. Equalizing weights on a scale is not a cognitive problem when the unit of measurement is standardized. It’s not so easy when the units are ‘whole language’ and ‘phonics’ or ‘grammar’ and ‘content.’ z scores? A pound is a pound. Three ounces of phonics and a tablespoon of whole language.

But balance is the anointed metaphor in the discourse, perhaps a political balance between two sciences of reading. Given its recent inclusion on the what’s a hot topic list, given persistent public concern with balance, given the undeniable link between balance and equity, let me suggest that one way to balance writing instruction is to integrate audience systematically as a master key to gravity.

Audience is a strong magnet in transactional writing (James Britton) where there is a bargain struck between writer and reader to collaborate on the meaning of a text, no funny business, a meaning that maps the real world—a report on seeds in cups on the classroom windowsill over time. As in a magnetic field, audience draws the writer’s eye as a compass needle flutters and then settles, pointing north, taking the reader on the same journey. Transactional writing signals a textual path for the reader to end up in about the same place as the writer.

Audience is a single spirit in a cloud in poetic writing (Britton). Poetry focuses not on bargaining over plain meaning in an actual world, but on evoking possible worlds (Jerome Bruner). Bruner called attention to the subjunctive mood as a linguistic bridge to possible worlds—what could have been, or might have happened, or would have been like if….

K-12 doesn’t typically do much with poetic writing which, unfortunately, isn’t part of the college and career balance. Writing transactional texts, however, can benefit from poetic ornamentation and flexibility to appeal to the spirit of a reader and provoke the magic of subjunctive response, the secret sauce of advertising, persuasion, political and legal discourse, and even academic writing. Nonetheless, the difference between text as signifier and text as art object is profound for writers and readers. Inexperienced writers need an appropriate balance between writing transactionally and poetically to develop literacy autobiographies.

A writer’s emerging sense of audience expands along with cognitive decentering, perspective-taking, with implications for more general cognitive development and knowledge construction. Through writing reports of information for authentic audiences, writers learn about the pistons, spark plugs, and distributors of textbooks, ready for content-area reading instruction and the essayist tradition, which isn’t all bad. Teaching fourth grade writers the five paragraph essay is child’s play when you’re also teaching them how to write verse forms. Suddenly it makes sense when words rhyme.

Taken together with awareness of purpose, audience has a) a feedforward effect during prewriting, drafting, and revising, making strategy instruction more salient; b) a motivational effect during editing and polishing making skill instruction more meaningful; and c) a reflective abstraction (Piaget) effect after text reception, elaborating on practical knowledge of writing in the classroom and in the world.

When inexperienced writers write for a null audience and produce transactional texts on demand and poetic texts for fun on holidays, unless they are writing in a diary, they struggle to find things to say, they lose their voice, they see no point in editing (Gravesian ‘manicuring the corpse’), and they have no inner executive reader to look at the text and its language from an audience perspective, to learn to parallel process a text-as-drafted alongside an emerging text-as-published, to perceive problems and possibilities, a form of authorial reading required to revise a text for clarity and impact and to judge the potential effects of substantive decisions. Writing in a vacuum means never learning how to read your rough draft and revise.

In addition to offering you some ideas about practical ways to think about audience as a foundational tool for writing instruction, in this post I hope to provoke your thinking about the relationship between audience and voice, between voice and language, between language and audience, as central not just to your teaching of writing or teaching of teachers, but to your own writing (and speaking) as a reformer in the workplace so vital in these troubled times. Our teachers will save us.

Strategic thinking about audience among experienced writers in administrative and leadership roles in public education has never been more important. This collaborative thinking must go well beyond the model of “public relations” where calming things down is the mission. Case in point from 2020: A team of scientific thought leaders in reading comprehension and its measurement was convened as a Visioning panel to propose ways to write a revised draft of a template for the NAEP reading comprehension test.

Their draft text recommended updating the theoretical framework of reading comprehension to accommodate the role of prior knowledge in reading comprehension. Essentially, the Visioning panel saw an evidence-based change to the template; measuring comprehension would be a matter of determining how appropriately a reader constructed meaning from a text given that reader’s level of prior knowledge of the content. Before ratification and publication of the revised test template, the Visioners were disrupted by the likes of Chester Finn and a small group of politicized audience crashers who, when asked for feedback, hijacked the text and turned the plane around. There was an audience inversion—the audience became the writer and wrote the text it wanted to see.

To this larger and more challenging end, i.e., the quest to bring equity to public schools, through the lens of a basic process model of writing emphasizing audience, I’ll analyze a local case of audience meltdown where a first-year high school principal lost her job in April, 2022, because she published a newsletter that didn’t sit well with the audience. And then the unsettled audience demanded that she apologize. She refused to take it back.1

When Amber Clark accepted the job as principal at Granite Bay High School in affluent, white, conservative Placer County, she came with experience as an equity administrator in the diverse nearby Elk Grove Unified District. She believed she had been chosen at GBHS to continue as she had been doing in Elk Grove. She made it through the paper screening, she rose to the top in the interviews, she was offered a contract. Throughout the hiring process, she answered questions about her experiences in Elk Grove and felt good vibrations from the school community.

Much of her job—like all administrators—depended on her communication with colleagues, including writing. During her initial months, alarm bells were going off in district headquarters. Emails were whizzing around as emails do, ending up in the inbox of her supervising assistant superintendent. Superintendent Becker suspended Amber Clark in April, 2022, too concerned about violation of her rights to fire her, but willing to risk a lawsuit nonetheless.

Clark was suspended for her part in publishing an April 5 email newsletter from the Wellness Center with information about resources for LGBTQ students. An earlier newsletter with information about resources for Muslim students had lit the flame.

Invention and arrangement are influenced by audience: What do I want to say to whom? Arranged how?

Audience considerations help writers make early invention decisions about topic and content. What to write about? What to say about it? These are the concerns of prewriting, drafting, and revising. Bringing a sense of audience opens up questions like what does this audience already know and believe? What arrangement of ideas would best serve my intention and their understanding? Too often, the only reader in the classroom writer’s mind is a teacher, and even that a shadowy presence.

Classical Athenian rhetoric separated the preparation of public oratory into four phases: Invention, Arrangement, Style, and Delivery. Each phase maps onto writing process stages with the addition of four cross-cutting elements that aren’t explicit in the process model: Audience, Occasion, Subject Matter, and Purpose. A writer finds a voice to address an audience about a topic for a reason. As I elaborate on audience, I’m going to give you an account of the metacognition that went into my writing of this post as I consciously emphasized audience in my process. Stick with me.

One way to think about transactional writing is assembling a text to communicate a specific something about a general something to a hypothesized someone. Rough, I admit. I’m very deliberately writing a transactional text. Decisions about content for this post, for example, have been made and revisited in light of the audience I envision—teachers and teacher-educators trying out ideas for balancing writing instruction and for balancing the scales of social justice. I know very few details about my readership, though it is growing daily. Lots of email subscribers with addresses ending in .edu, some .org, some Gmail.com.

Since my readership responded by growing in number as I posted more theoretically contextualized posts involving my experience, I decided to draw from two pockets of practice in my own teaching of writing over an eight year period and provide specific examples of bringing audience explicitly into the writing process classroom. The first involves a) community college teaching of English 101 over a five year period; the second, b) teaching writing in fourth grade for three years. We have a comment tool in Substack if readers are moved to enrich this post with insights and experiences.

I wanted to find a real world example of administrator-as-writer not grounded in my own history—I’ve worked with several principals who understood the power of a well-written memo—but came up dry until I opened Sunday’s paper and saw Amber Clark’s headline. Beyond words. Her experience led me to a theoretical analysis of a type of audience I’m calling a hegemonic audience that usurps the voice of the writer and takes it over through ventriloquation and heteroglossia, two terms used by the Russian literary theorist Bakhtin, which I’ll discuss in the conclusion. A version of a hegemonic audience usurped the voice of the Visioning panel in the NAEP test template revision project and wrote the template it wanted to see.

Arrangement of ideas is done to facilitate and impact audience comprehension.

I knew my post had to have a clear thesis statement to provide readers with a stable organizer (audience as key to writing instruction) to achieve coherence across four layers of development: 1) teaching first year composition in an official, voiceless, structured curriculum, 2) teaching fourth graders to write with their own voice for an audience in a non-existent curriculum, 3) my metacognitive account of audience as key to the creation of this post, and 4) Principal Amber Clark and the inadequate district administration protocol to guide her development of a theoretical audience. The phenomenon could have played out differently had she been administratively scaffolded in her early weeks.

The arrangement of these experiences in this post and the LGBTQ newsletter episode, I decided after trying some options, would be chronological. I would develop the thesis (audience as balance) and provoke my readers with Amber Clark’s story in the intro. Then I would look back to my college teaching experience (1981-1986) , and to my fourth grade teaching(1986-1989). I would end with an analysis of how a Board President’s being offended by a newsletter led to the Superintendent ordering Clark to email an apology to the community.

Style, register, and diction should match audience expectations for the genre

This post is partly exposition, partly narrative, voluntary reading for self-motivated professionals. Sentences should be uncluttered, and words should not draw unnecessary attention to themselves as esoteric tinsel or tired jargon. If I use an academically laden term, I’ll make sure it’s vital to the thesis. The post is not a report of scientific findings or seductive theories, but an exploration of an instructional balancing act and a narrative of pragmatic strategies. Words must be precise. Words associated in the discourse with particular theorists require attribution where possible.

Delivery: Experiences with real audiences produce more powerful learning

Walter Ong (1988) commented on the paralysis that ensues when a writing assignment is designed without audience:

Reception in history is the difference between a fictional and a real audience. I watch my wife read my drafts of these posts as I work through revisions. The pauses, the regressions, the expressions—I have to watch her progress through the text to get a sense of coherence and flow. I can talk to myself until my central executive is blue in the face, but the truth maker is the reader. The reader brings it on. I’ve received general feedback from several readers on these posts with much appreciated help and encouragement from several of you in ways some of you may or may not realize. Writers who never experience feedback from an audience for whom a text is shaped never have the chance to find out if decisions worked. Early and sustained experience with real audiences in the elementary years could produce enough reflective abstraction from empirical audiences to make unknown audiences not fictional but theoretical.

Reflective abstraction is a Piagetian term. Think of a lion, a cow, and a dog. Each schema is distinct, made from an organized set of concrete specifications that prevent lions from becoming cognitive cows, cows from becoming cognitive dogs. The cognitive move to organize each concrete schema as an abstract animal is reflective abstraction. Reflective abstraction is Piaget’s word for the cognitive work we do to construct a network of knowledge at varying levels of abstraction to integrate and differentiate incoming information. Animal doesn’t map onto the world. It is an abstraction that reflects the real world through subsystems like lions, cats, and dogs. Audience is an animal; the path to the abstraction is reflected through concrete experience.

The difference between a theoretical audience and a fictional audience is night and day. A theoretical audience can be construed for a particular writing task through comparison and contrast of experiences with real audiences. Amber Clark could have been scaffolded to create a theoretical schema of local audiences through detailed history lessons about the school, in-depth discussions of previous equity work projects, role playing with members of the leadership team, and strategizing about upcoming occasions for writing and public speaking that would minimize risk of communal disequilibrium and maximize long range effectiveness. She may have decided to limit her use of the term equity on her own—or maybe to use it differently. But she would not have been put in a linguistic cage during her second month on the job.

She was ordered to stop talking about equity. That’s like trying to get me to stop talking about reading and writing. It’s not going to happen.

Inviting Audiences into Writing Instruction in First Year Composition

Writing assignments in college classrooms can be arranged along a continuum of degrees of shared understanding of audience between teacher and learners. When I taught part time at two community colleges in the early 1980s, my students told me of fear of writing assignments in required courses because they didn’t understand what the professor expected. One student enrolled in an inhalation therapy program was being asked to describe a lemon. He was beside himself, he found the assignment so sour. He had to pass the class or go back to his old job as an auto mechanic in a Shell station.

As the primary audience, occasion, and purpose for learners to practice writing, teachers of writers in English Composition 101 are expected to provide explanations, models, strategies, structured assignments, guidance, and feedback for learners in sections usually of 30-35 students. Since the 1890s when Harvard began requiring this first year course, the idea is to equip newcomers to college with writing skills that would serve them in their studies.

This teaching obligation usually meant following the contents of a composition textbook with chapters on the different modes of essays, complete with example essays with discussion questions, and so on. English Composition textbooks are notorious for staying power in the marketplace for decades. Alexander Bain’s seminal textbook on composition for the masses from the mid-19th century stripped away audience, subject matter, and intention. Bain boiled the challenge of learning to write to mastering the the paragraph. The word is to the sentence what the paragraph is to the essay. For the past century plus, American writing instruction puts mastering the paragraph as a third grade learning outcome, mastering the essay as a sixth grade outcome, mastering the five-paragraph structure an outcome of high school. No matter if the essay is about vegetables or organic chemistry, audience and purpose are irrelevant.

In dozens of freshman composition courses I taught at two community colleges, I asked my students to view me as responsible for being clear about what I wanted them to do for their assignments, and as an assessor who would give them feedback including grades on their compositions. I would provide feedback in office hours during and after production. Personally, I enjoyed working with their papers to witness their ingenuity in solving writing problems, and I always gave a prepared lecture, a post mortem after grading their work with specific examples from their work as prelude to the next assignment. I favored positive examples and watched for them. I limited negatives to general problems, anonymous problems, often technical but few in number.

I was doing a side gig as a writer of articles for popular periodicals at the time, and I made it a point to talk with my students about the articles I was writing. I told them about how, before I tried to publish in, say, Weight Watchers magazine, I found magazines I wanted to target on the shelves in book stores and studied them, trying to locate the implied reader. I needed to reflect this reader’s expectations and tastes in my texts if I were to get a contract. This was during the epoch of Writer’s Market, a book cataloguing publishing opportunities from Ford Times to Runners World, back when freelancers wrote hard copy query letters to editors. I published often in Shape, a magazine for the health conscious—never under my byline. 1,250 words for $75. Usually, the author of record was an MD.

I encouraged my writers to envision a readership or an audience for their essays apart from me before they committed to a topic. Many of my students were in associate degree programs with certification to qualify for a specialized position; I encouraged them to choose topics that would be of interest to their future co-workers. Sometimes writers found occasions for writing in their daily lives. An interest in learning the process for making world class spaghetti, for example, could result in a motivated essay of process with mild documentation that had peers salivating.

Discussions of readerships were mediated by questions on the board. “Tell your neighbor three topics you are considering and what readership might have an interest or need in the text.” I emphasized the importance of due diligence when selecting a topic for a classroom writing assignment when you have a choice. Topic can make all the difference. Sometimes you just have to bite the bullet and describe a lemon as if your life depended on it. But writing is so much easier and enjoyable if you spend quality time thinking before taking the leap of faith. Maybe not a lemon.

Freshman Composition then and likely still today was driven by rhetorical structures. Description could be organized chronologically if the subject required it, e.g., describing a swimmer, but more often spatially or topically. Narration could be organized on a time line as well, but staging concerns could rearrange the order (what does the reader need to know when?), and shifts in setting provided means for parallel time lines (meanwhile). I didn’t have much time for description and narration. The bread and butter was expository writing—essays of process, report, comparison contrast, cause and effect, problem solution, question and answer, explanation, all leading to argumentation, just in time for winter break or summer.

I had one experience that I still haven’t fully processed in my own psyche. In an earlier post I discuss my experiences teaching First Year composition in a maximum security psychiatric prison. For two years I read essays that addressed one of two audiences no matter what I said or modeled: They wanted to write for readers who might look at an inmate’s individual case sympathetically and do something or at least feel outrage at the injustice of their being in prison—or readers who needed to be enlightened about the failures of the correctional system or the corruption of the courts.

No matter what rhetorical structure I was teaching, I got a continuous flow of the same ideas. I never had the sense that the inmates were writing for me, the instructor, probably because I found it difficult to make substantive comments on their papers. I looked for interesting uses of commas. We talked about the semicolon. I cracked open a box of schemes and tropes—anadiplosis, antimeabole, chiasmus, periodicity, stuff from my classical rhetoric course back in 1975, how to put lipstick on a pig.

The prison population was bifurcated with the majority seriously undereducated and in need of phonics and a small minority seriously smart and knowledgeable criminals. One of my writers had owned five automobile dealerships before he was convicted of running a drug smuggling ring. Heaven forbid the guy became a master writer. These courses took me to the edge of my instructional skill levels.

Inviting Audiences into Writing Instruction in Fourth Grade

From 1986 to 1989, I was fortunate enough to have found a position as a fourth grade teacher. I’m going to draw a few paragraphs from an earlier post to elaborate in this post.

In my classroom, fourth graders wrote all day. The biggest challenge for me instructionally was to create conditions for real audiences to read their stuff, especially beyond the classroom. I actively worked to dissolve the examiner audience, the red pen, the metaphorical literacy hall monitor. But I knew that writing isn’t real for most of us without an audience, at least not transactional writing. By the way, transactional text can be narrative or expository.

Structure, grammar and syntax, orthography, and punctuation are subject to deep and surface social, cultural, and linguistic rules and regulations that must be learned and followed in both academic and real world settings, but counting and highlighting errors doesn’t teach anyone anything about writing. I was reading Donald Graves as I looked for guidance, and he insisted that firsthand contact with an authentic reader where a writer finds out what happened when a reader took up the writing—that’s the moment of electric shock. Oh. They didn’t understand what I was trying to say, says the fourth grader.

At first I drew on the students themselves as audience, a strategy I’d used at the community college. I taught them to distinguish between a) discussing a rough draft with a small group for feedback and b) publishing a final copy during Author’s Time, the time when a student by formal prearrangement occupies the Authors’ Chair and reads a piece aloud to the class. Student authors published pieces in various bindings in the class library (we developed a collection of student-authored story books with illustrations for checkout to take home).

I taught them different purposes of feedback. I taught them how to ask for feedback, when to seek it. The connection between spoken word, audience, and written word came in its totality as they talked about early ideas for writing projects. Writing happened awash in talk. I wanted to drum into their thinking: A piece of writing grows from thinking, planning, and talking about it in a community of writers to a polished and published text.

My second year I devised two strategies for integrating parents, an ever present resource, most of whom worked during the day, as absent presences in the classroom audience—the Daily Parent Paragraph and the Parent Reader Program brought written feedback to the class from their collective set of parents.

The Parent Reader program was a deliberate, school-wide strategy to which my principal lent support. The idea was to organize and train a group of parents to read and respond as readers to rough drafts of writing children in grades 3-6 were working on in class. Children would read and consider this feedback and revise their work, taking feedback into account.

Logistics involved recruiting volunteer parents (working parents who wanted to help but couldn’t be on site showed up in large numbers) and organizing them into teams we could designate to specific classrooms. Parents would not be assigned to their own children, and children would never know the identity of a parent reader. Teachers monitored parent feedback for potential problems and followed up with the program coordinator (me).

Parent readers worked in groups of four assigned to a classroom. They expected to receive a packet of rough drafts from their assigned class (usually 5-7 pieces of writing) on Friday afternoon and return the drafts with written feedback on Monday. Volunteer parent couriers delivered and returned the packets. Teachers provided class time on Monday for student writers to read the feedback from parent readers and to talk about their reactions and questions. During the second year we had approximately 40 volunteers. Parents appreciated the opportunity to support the school in a meaningful way.

Training the parents and the writers in the same feedback protocol cemented the distinction between formative and summative feedback. Parents overlooked spelling, handwriting, and punctuation—those belonged to the teacher. They were readers, letting the writers take a look inside their heads while they were reading.

First, parents and children alike wrote feedback to this question: When you finished reading the draft, what was the most important idea or theme you got from it (receiving the piece)? Second responders wrote to this question: I really liked when you wrote ______ because… (the pointing response). During training I emphasized that this response increased in pedagogical power to the degree that the reason for highlighting that part was authentic and specific. Writers are apt to do more of what readers point out as effective, especially if they understand why it was effective.

The third response, the wondering response, was the place to respond to this: As I was reading, I wondered about…. Sometimes this response involved pointing to a specific, but sometimes not. During the first year, I analyzed revisions from rough draft to final copy mediated by parent feedback and interviewed my students to find out how they used feedback from parents. Unsurprisingly, I found that response type one (receiving the piece) either confirmed for the writer that the text was working or it was not; if it wasn’t working as planned, writers wanted to talk with me or with peers or both. The pointing response led them to develop a feel for pacing, imagery, dialogue, emphasis, direct address to the reader, and more.

The wondering response was less predictable. At a basic level writers would rewrite and answer questions by tacking on sentences. I learned that my students’ attempts at local revisions far surpassed their global revisions, and that global revisions were likely stimulated by a reader who wondered. For example, one boy whom I worried about because of a general lack of engagement wrote a quick draft one Friday just to get something in the packet (kids didn’t like it when the packet came back and there was nothing for them). I told him to write about things he could do to improve his grades to prime his pump. The following Monday I saw more frenetic writing activity from him than ever before when he got feedback and revised.

His rough draft had been a romantic list of ideas (don’t watch tv all night, come inside before dark, study anytime you can, like, study your multiplication facts while you’re waiting for the bus). His parent reader, who had written him notes back when Jimmy had not put in a rough draft (I missed reading your paper, Jimmy), received the piece thusly: I read about a list of good ideas for improving your grades. He pointed to studying at the bus stop as a particularly good example because it showed determination, and then he wondered: Do you do what your paper says? Jimmy made some profound changes in the final version. He kept the original list of good behaviors, but he added a contrasting list of things you shouldn’t do, including ‘don’t do anything you’re not sposta.’

“My Daily Paragraph” was a content-area strategy designed to engage parents and other family members in the child’s writing, to validate funds of knowledge in the home, to teach the writers that finding out what other people know through interviewing them is a powerful invention strategy, and that writing up a report back is important to sharing information with an audience, in this case, peers. It reversed the typical “What did you learn about in school today?” from parents. Instead, it was “We’re studying Father Serra in class. What do you know about the missions, Grandpa?”

For math class, I would have my students ask someone, an older sibling, a neighbor, a parent, a question like “What examples can you give me of ways we use measurement at home?” A child one day excitedly reported that her grandfather had been having trouble with a new set of ill-fitting false teeth; he explained to her that the dentist was going to have to remeasure and fix the set. I found questions easily that produced surprising and interesting results: Why do we have Veterans Day? What fertilizers have you used to grow plants? Sometimes kids reported “my dad didn’t know much about why they grow grapes in the Napa Valley and he wants me to tell him what I learn.”

I set up classroom magazine groups with student editorial boards who worked with writers to publish articles about pets, skateboarding, music—topics and foci determined by the boards in consultation with the publisher, Mr. Underwood. Editors had to write a letter of interest in the job with ideas for the magazine to me. Class-made magazines could be checked out from the class library and taken home. Copies of issues were made available to students in other classes. I saw promise in this strategy, but it was more difficult to expand and sustain. If I were a principal, I think I would look at getting a safe, secure school publishing center for learners online.

The 90-minute writing workshop held every M-Th from 9:00-10:30 began with a mini-lesson followed by a status-of-the-class where I called each child by name and listened to progress reports and statements of intent for the day’s writing: “I’m going to work on the Space Ship in my Back Yard. I need to get some ideas. I want to have a conference with Brad and Laura to get some feedback on some details about how to make it fly.”

My third year of teaching writing workshop-style, I had a dozen children writing novels, working on them late at night and on vacations. The third grade teachers were by then teaching workshop-style, we had collaborated on a kid-organized school newspaper, we were doing cross-age writer response groups, and my kids were inviting community stakeholders to poetry readings with refreshments. The last cohort I taught had had a year of workshop under their belts before they came to me. Upper grade teachers told me their students were demanding writing workshop.

Finding a Voice for Equity as a Public School Administrator

Amber Clark appears to have been motivated to do well and continue her equity work at GBHS. She would lead from a position of responsibility and authority, which meant she would write the agenda for meetings and shape the discourse of the school. Superintendent John Becker, who would be starting his first year in the district as well as its top administrator, had these words to say in July about Clark in a web address posted on the district website:

“These passionate and fresh pairs of eyes bring a new perspective, a benefit to us as we reimagine who we are as a district and how we work together to give our best to students each day.”2

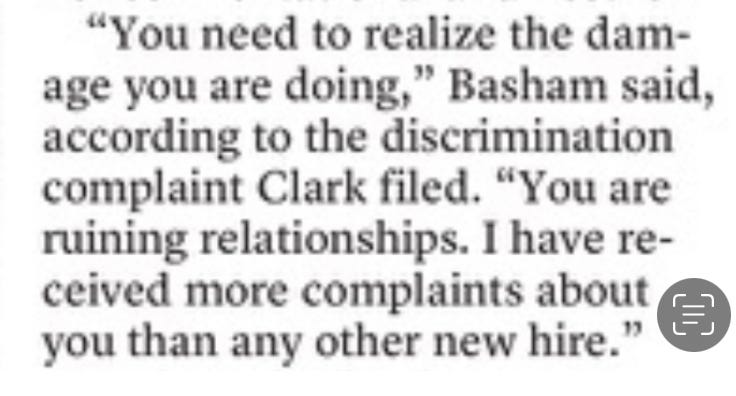

It’s not apparent whether the district office had prepared any paths into the culture of the school and the district for Clark and her “fresh eyes,” but the Bee article quotes a supervisor delivering feedback to her in October. Rumblings of discontent made their way to an assistant superintendent:

How might this conversation have gone differently? For starters, Basham might have positioned himself as a colleague, not as a boss. The assumption that because people complained, Clark did something wrong is unsupported. “You need to know that people are emailing me with complaints,” he might have said. “I’d like to do whatever I can to support you, and I know how hard it is to talk about equity, especially in this district. What do you think?” Later, Superintendent Becker, who likely had had his own share of duck and cover experiences, tried to transform her into a stealth worker near the end of the fall term, 2021.

This pivotal moment is a missed opportunity—much as the NAEP test template revision work directed by a Board missed an opportunity to dig through the political detritus distorting the Visioning work. Given the centrality of the concept “prior knowledge” in the conflict, given the unquestioned expertise of the Visioning panel balanced against the naive understanding of the objectors, the Board could have sponsored sustained, in-depth presentations of the science around prior knowledge and comprehension by the Visioning panel. The most accomplished researchers in the field were available to the Board.

In December, 2021, John Becker put his finger on the master schema that would explode in fragments on April 5, 2022. Equity—like animal—is a reflective abstraction rooted in concrete experiences. Subjunctively speaking, I can envision Becker sitting calmly with Clark, talking about her understanding of equity, learning from her, telling about her community, working together to discover the reality of the audience of stakeholders they shared.

“I’m sure you know we have a robust Mormon population in the district,” he might have said. “Mormons have been in Placer County since the days of the Gold Rush. Our Board President is Mormon, Mr. Huber. Have you met him? We had a brush up in the school community in 2008 when Proposition 8 was on the ballot, banning gay marriage. The Mormon community was dead set against gay marriage. We had angry protestors on campus. But around 2015 at the national level the church started changing. Now, the doctrine has changed; they have a website with videos of gay church members telling their stories about being accepted.”

Instead of locking down a word, he could have excavated the site and offered to collaborate with Clark on strategies to educate the “pockets of misinformation and disinformation in the community.” He could have supported her in understanding her audience to help her make knowledge-based decisions about her communication with them. He could have viewed Clark as a writer learning to address an audience.

But he didn’t for reasons only he knows. His head could have been on the chopping block as well—even more reason to collaborate with those “fresh eyes.” In February district officials directed teachers to discontinue reading Grading for Equity, a book Clark had recommended for a Book Club. Several teachers in the club emailed officials for an explanation, but there was none. The command to silence those speaking about equity was the work of a hegemonic audience, an audience gradually inverting the writing process to become the author of its own text.

During this period, prewriting of the Wellness newsletter was taking place. The district had adopted a wellness center model and installed a group of district-level personnel to coordinate the project. Details of the newsletter writing process are murky. Amber Clark was working with an assistant superintendent, Moore, another new administrative hire in 2021, in the Wellness unit on the newsletter. Email correspondence reported in the Bee reveal that Clark and Moore discussed a revision of the newsletter. Moore warned Clark of a backlash.

Clark requested that Moore enlist the district’s outside public relations firm, a potentially job-saving move. Here is Moore’s response:

I wonder how much the firm would have charged for a review and whether the review would have surfaced solutions to the conflict. When the newsletter was published, the Board president, a member of the Mormon church, emailed the Superintendent and demanded that the Wellness Center change its ways. The newsletter included a link to a video featuring a Mormon father making a plea to the church to accept his gay son:

In fact, the church had undergone a doctrinal change around 2016 since the production of the video:

The Superintendent responded to Clark:

When Clark refused to apologize, Becker suspended her and she found another job. The district now faces the possibility of a lawsuit.

Amber Clark was stopped from using her voice to do the work of reinventing a public school community so that religious beliefs and racism would no longer prevent access to resources for marginalized students. Why? A hegemonical approach to audience—trying to write the text the audience wants to read.

Had Becker had a sustained conversation with Clark about equity, the master schema, in October, had Moore secured access to the outside public relations firm, had a strategy been implemented to take seriously the crucial significance of a sense of audience, perhaps the newsletter might have served as the occasion to trumpet changes in Mormon doctrine. Mormon children need no longer fear coming out and having to leave the church.

In September, 2022, the district reported the conclusion from an independent investigation that it “handled complaints about the newsletter appropriately” by suspending Clark. Time will tell what the legal system decides.

https://amp.sacbee.com/news/local/education/article260857132.html

https://www.cnn.com/2015/01/27/us/mormon-church-lgbt-laws

https://amp.cnn.com/cnn/2016/10/25/living/mormon-gay-website/index.html

https://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/topics/gay/videos?lang=eng

https://www.rjuhsd.us/superintendent