“…[T]he problems of philosophy are of such broad relevance…, and so complex in their ramifications, that they are, in one form or another, perennially present. Though in the course of time they yield to philosophical inquiry, they may need to be rethought by each age in light of…its experience.”

(In Virgil Aldrich, Philosophy of Art, 1963; words written in the series Preface by Elizabeth Beardsley and Monroe Beardsley)

Children in California schools during the policy change from NCLB to CCSS remember when it happened—2010, when reading complex assignments slowly, analytically, bumped uncomfortably against reading easy books on a treadmill. It seemed as if the divide between teaching reading comprehension as disciplined work and encouraging reading casually for fun divided teachers, even within the same school.

The Million Word club of double diamond readers, reading for points, was morphing into the FRUIT group study club scouring texts for evidence, annotating like crazy, reading for grades. “I gotta find a new book to read” became “I need to find a symbol, three metaphors, and a good quote.” Common Core architects suggested it might take six-eight days of class time to read “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” which is under ten pages long. NCLB adherents under the influence of the quest for fluency and automaticity and Chall’s “ungluing from print” expected students to read two or three novels in six-eight days.

It’s been enlightening to learn from Justin and Jassi, recent high school graduates and ltRRtl podcast participants, that Core reading in certain classrooms brought new lenses to look at language as the paint and the brush of literature. Aesthetically satisfying illusions evoked through interaction with literary texts can be analyzed structurally and functionally through disciplined and focused cognitive work, and the fruits of the analysis can be expressed in argumentative prose. When analytical reading is taught as a part of the big picture, it holds great potential as a pedagogical aspect.

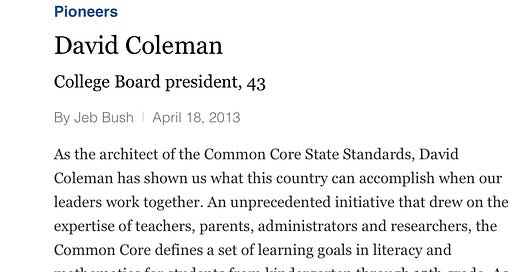

Widely acknowledged as the architect of the Common Core, current CEO of the College Board responsible for the Advanced Placement Test program, David Coleman, has been praised not just for his hands-on educational leadership, but for his political contributions. Close reading every day all day long constitutes his mark on the substance of the ELA Core. Witness his praise:1

What, exactly, David Coleman showed us “this country can accomplish” remains unsaid in Jeb’s accolade, a gaping hole in a hollow paragraph, a hundred words summed up in a simple clause: “45 states have put aside their differences.” In the way that SSR and literary analysis “put aside their differences?” Read from a distance, casually, Jeb’s jubilation is actually his relief that Trump’s future would be postponed, not a celebration of accomplishment. Wait… now is not the time. There was something seductive about these Core Standards that attracted both Democrats and Republicans. Read from a millimeter away, “higher standards” remains a political slogan and a deictic reference.

***

Some explain close reading’s emergence in the Core as a response to a plea from college professors, particularly English professors, to teach students better comprehension skills before sending them to college. Maybe. I’ve not seen a reference from any source suggesting that labor unions or corporations issued a plea for better comprehension instruction in the workplace that led to close reading. A Rhodes Scholar who studied English literature at the University of Oxford and classical educational philosophy at the University of Cambridge in the U.K., Coleman likely had his own pygmalion concerns about lackadaisical practices encouraging reading more for fun than for profit. (As near as I can tell, he was agnostic about the Science of Reading, a conclusion I reached after hearing Louisa Cook Moats express intense disappointment with the Core vision of early reading instruction.)

Responding to this plea from English professors with funding from and access to Bill Gates, Coleman leaned on premises of the New Criticism, a set of academic prescriptions for scholarly literary critics from almost a century earlier: Readers of complex texts must stay within “the four corners of the text” and make claims about meaning based on “textual evidence.” Witness the following advice from an educational website offered online to student readers as a guide for their behavior in accordance with Core norms :2

Closely reading this advice, one might argue that the hero/author/persona of this snippet of text, the one standing up as mentor, leader, an authority, is not a poet. “Great poetry seems to be able to withstand rereading” belies either a lack of experience or an impoverished theory of reading or insincerity—or of condescension. “Great poetry” is objectified as a fortress that “withstands” attacks from vigilant readers—it doesn’t crumple and fold like a trashy novel.

Then “great poetry” is personified as a Zen master who “encourages” challenges from novices, daring readers to capture its essence by shows of intelligence. Ruled by the laws of military engagement or positioned as a grasshopper, I’m not free to interpret at will but am restricted to think only about what I can “back up.” So I have a chip on my shoulder. I have something to prove. While I’m reading, I’m warned not to try to “solve” or master the poem; read with proper humility.

Is this the way people read poetry? I ask myself. Is it against the rules to bring up the fact that I sometimes read poetry before I go to sleep as a pre-dreaming activity? Then all of a sudden, I realize, burrowing ever more closely into the cracks of the text provided to guide me. It’s no longer just a poem we’re talking about—it’s a poem “or a passage,” and because I’m reading closely I see that these instructions aren’t about just reading a poem, but reading anything at all.

The concluding sentence cries out for, but doesn’t really repay, really close reading: “reading a poem is a kind of experience,” the mentor text, what, says? (idk what to say). And while I sink my sharp skills into that one, here comes the hyphen and the zinger: “a real experience.” Help me solve this puzzle, O teacher, I’m stuck between a real experience and I guess a fake one—and I’m getting graded on it.

***

It’s clear that close reading has infiltrated to the core of the literacy curriculum displacing the more generic “reading” as the preferred outcome of instruction. A proliferation of mnemonic devices (e.g., FRUIT: Focus, Read, Underline, Identify, Tag) to put a regulator on free-wheeling jetacognition (self-propelled metacognition a la Tom Cruise and Maverick) is all over the Internet. Many of these mnemonics put me in mind of what little I know about neural networks and machine learning, aka Artificial Intelligence. The FRUIT mnemonic in particular ends with “tag,” a resonant, fragrant metaphor.

The following excerpt comes from a flyer for a book published as a resource for teachers working with adolescent readers. Pre-Core I think this approach would have caught my eye as a middle school teacher. It’s pretty ingenious in its marriage of close reading and free reading. I think in practice I might have adapted it from its deductive framework to a discovery framework. Robert Probst, one of the authors, is a heavy hitter in the domain of aesthetic reading. The array of STOP signs could support a reading portfolio strategy in a self-selection classroom. Having analyzed a zillion adolescent novels, the authors distilled a set of six “signposts” for teachers to alert their students to as STOP signs during reading acts to pay attention, close reading zone ahead.3 Witness:

I think I would also incorporate SLOW or YIELD signs pinpointing places on the reading journey where readers might want to attend to how they are responding emotionally or personally, whether they spontaneously link their reading to another text or another reader (“I can’t wait to talk with Samantha about this scene—she has an autistic sibling”).

What concerns me about these signposts as pedagogy depends entirely on implementation. If we were talking about machine learning, these are exactly the kinds of loops machine learning might first identify in adolescent fiction—learn the formula—and then as AI apply to the writing of artificial fiction. chatGPT and the other artificial brains now in infancy will be fully capable of doing this kind of close reading and mimicking “original” texts to assign in classrooms to be read by students who test to earn points to redeem for brag tags.

***

The philosophical roots of close reading grow in the soil of a modern Western theory of literary analysis called the New Criticism. Debates in the 1930s between leading voices like T.S. Eliot, a poet, and I.A. Richards, a linguist and psychologist, about the uses of literature in society—whether literature was to be seen as a “handmaiden or a savior” (see Eliot, The Use of Poetry, the Use of Criticism, 1932/1964, p. 128) of humanity—were one part of the argument. The other part was the debate about how to interpret meaning and assess beauty, which came down to the writing of a second text, an essay, an argumentative text on top of the aesthetic object. David Coleman tapped into this second thing, the essay, as the core object of writing instruction in high school. What is poetry? How do we use it? How ought critical analysis properly treat it?

***

A key difference between a text as an object of art and an interpretive essay about a work of art, for example, a critical essay arguing that Hamlet is a lesser play than Macbeth (see T.S. Eliot), is profound. The art object is an end in itself, functioning as a provocation of strong emotion, refiguring consciousness in its graceful artistry, intrinsically satisfying. Many of us do this kind of reading regularly, even daily. The critical essay is a means to an end, an argument for an argument in a scholarly context or the completion of an assignment for a grade. Literary critics do this for a living, students do this to prepare for life beyond high school. Most of us don’t often write such essays.

Readers have every right to experience the illusion emotionally without the burden of having to solve it or master it or back your interpretation up. Making explicit the elements that work together to evoke the emotion in itself can be satisfying, enhance and deepen the experience itself, and often happens during book clubs or over coffee after the movie. The serious critical stance, if it is taken up, comes later, certainly not a routine applied to everything you read. Lots of excellent, persistent, devoted readers read through ambiguity and detail for pure enjoyment without fear of being branded a slackard or an ingrate or a careless bumbler. They take what they want and come back when they want.

New Critics agree that texts as art objects are made to evoke a unified, formal experience, a phenomenological illusion calling on engaged prehension and sensate ideation, Coleridge’s willing suspension of disbelief. The aesthetic experience of illusion is the motive for reading the literary text, the illusion framed by language. But analytical readers set aside the illusion, the feeling, the human connection and instead gaze into the inner workings of the textual object.

The task is to evaluate the artistry in language used to structure a coherent, formal experience capable of evoking a sustained, pure emotion. Macbeth succeeds in every detail in evoking the sensation of revenge—check it out on SparkNotes—while Hamlet evokes, what, sensations of friendship, loyalty, revenge, betrayal, madness, fear of death? That’s the problem. It’s the fragmentation, the indeterminacy of Hamlet that makes it a weaker play. Thus sayeth T.S. Eliot.

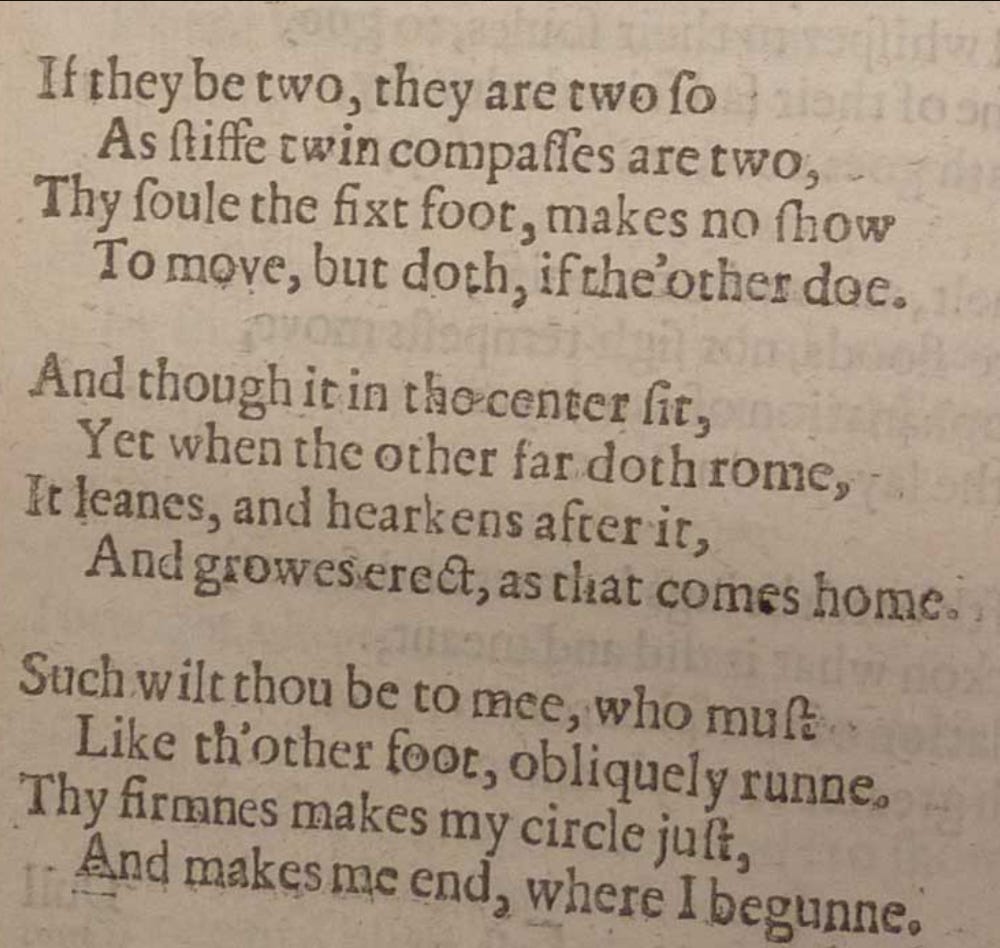

Because the legitimate feelings evoked, the hair raised, the tears shed, were not the point, the metaphysical poets like John Donne, for whom the bell tolls, who suffered in literary purgatory for centuries for their cold, technical, odd figures, were rejuvenated in the light of the New Criticism. Donne’s “Valediction Forbidding Mourning,” criticized for its wrenching, some say violent use of the compass as a metaphor to express the timeless, spaceless connection between two lovers, came into the sun in the 20th century when the metaphor was appraised not for its emotional impact, but for its formal aptness and structural complexity—the compass a tool of navigation on the sea, a pair of lovers separating in anguish, the compass with two legs spread apart yet joined at the top, the pair of lovers joined in some Platonic abstraction—you get the idea.

***

Aldrich (1963) referred to John Dewey’s philosophy of “art as experience” which provides a potential way to harmonize analytical reading and free reading. For Dewey, an aesthetic experience “…must achieve not an exclusion of various factors ordinarily present, but an inclusion more comprehensive than usual, presenting a felt unity of the elements that appear more scattered in routine perception” (Aldrich, p. 18):

“…[S]uppose…an artist in gastronomics is preparing [a soup]. This…involves…delicate operations of adding and balancing ingredients…[at] the right temperatures for the right duration…under the pervasive influence of the end sought, which is the control on the operation. The final partaking…will, for the connoisseur, be a consummation in which the productive operation is felt—even tasted… ” (Aldrich, p. 18).

Dewey’s position distinguished the aesthetic event not as categorically different from ordinary experience but as a particular kind of experience, one centered around sensations, joy, a “felt unity” of experience. The experience of eating a quick bowl of beef flavored ramen at lunch doesn’t begin to touch the “ideated sensation” of eating oxtail soup for dinner, but the logical consequence of limiting the category of aesthetic experiences only to the finest silk of texts denies the existence of aesthetic apprehension in more ordinary or less exalted experiences.

The question of priority—analysis of text as machine or its evoked experience?—isn’t easily resolved. Eliot in particular argued that readers ought to interpret the meaning and worth of poetic texts on the text’s terms, setting aside evidence from elsewhere during interpretive acts, that is, evidence for interpretive claims not closely tied to the facts of the text. Putting the experience of eating of ramen on a continuum with that of eating of oxtail soup isn’t Eliot’s concern. The chef who made the soup is similarly irrelevant. The operations applied during production are also immaterial as are the intentions of the maker.

Scholarly work in academic disciplines involving literature, like all scholarly work, is carried out according to rules of discourse. Privileging literary texts as autonomous expressions of unreality situates the act of interpretation and valuation in the space between reader and document. What the author wrote or said about a text might be interesting, but not relevant. Committing the intentional fallacy, i.e., looking for what the author intended, is a flaw in an interpretive argument. Whether the chef intended it or not, the bitter in the sweet is still bittersweet. Similarly, relying on reader responses to a text to argue for particular interpretive claims is folly—the affective fallacy. Subjectivity blurs clear analysis of textual facts. Although aesthetic experience is subjective, it is not ordinary experience since it is imaginary. Critically appraising the object of the experience should be done almost scientifically, certainly dispassionately.

Close readers may legitimately feel emotions, just not during analysis. Giving voice to these emotions to support an opinion about a text could be appropriate in a classroom community. I may not like oxtail soup, but I can say I don’t like it without having to defend my dislike even as I praise the artistry of the chef. I may feel disgust about pedophiles, but if I’m interpreting Nabokov’s Lolita I must learn to set such disgust aside to appreciate the artistry. Disgust is not the point in literary critical analysis.

If the object is to identify evidence inside the four corners of the text to support an interpretive argument, ask me to do it once in a while—but let me eat regular food, too.

***

Close reading could be useful as an insidious way of defanging literature. In The Republic Plato solved the problem of literature, that art sets out to create illusions by deception, by banning poets from utopia for moral and metaphysical reasons. Reading literature is subversive activity because the text shapes the percipient’s consciousness and determines what they will “see.” Close reading shifts cognitive focus from responding to what a text means or evokes to how it works to mean or evoke what it means or evokes—an objective approach to pulling back the veil on subjective illusion.

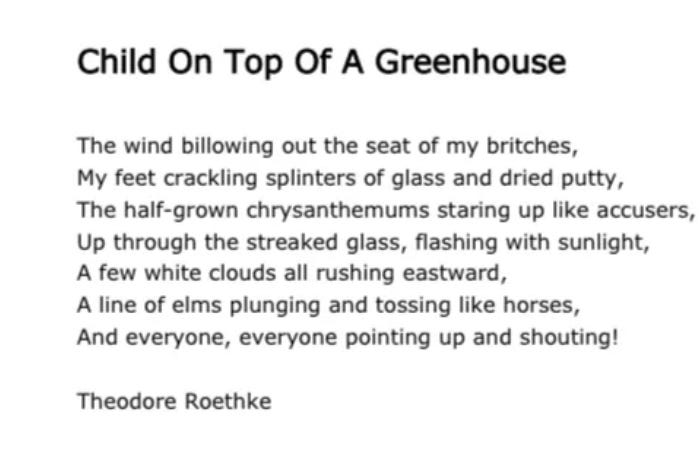

It’s important to note that close reading does not mean eliminating prior knowledge gained from prior experience entirely. Linguistic knowledge about words and texts (this is a short story, not a play), vocabulary (the text is about a greenhouse, not a plowed field), and inferences (the police found the murder weapon and gunshot residue on the butler) are in play. But validity regarding the text’s horizon of meaning is warranted by specific words or signifiers from the text, not from beyond the borders. Interpretation is done objectively under the umbrella of the text using evidence obtained with a search warrant.

***

In contrast, from a different part of the academy in the early 20th century, from psychology, anthropology, philosophy, and linguistics, critical reading denied these restrictions on evidence and required readers to examine extraneous signifiers and circumstances—the occasion for the writing, thoughts and purposes the writer espoused in life, how the writer was raised as a child, love affairs the writer might have had, political movements or ideologies the author embraced, the zeitgeist in which the text was produced and received, these elements are central to a critical reading. This approach also seeks to pierce the illusion artists seek to create by requiring the reader to step out from under the umbrella of the text to discover what the text might be hiding or not saying.

An initial step in this approach is a deliberate effort to understand the writer’s milieu, including personal and social history and shaping experiences. In some sense, this sort of reading is reading the writer, looking at the text as the presentation of symptoms of the historical condition underlying its production. Writers themselves are written by their times. Working with their texts in the light of contextual knowledge brings readers closer to interpreting a text’s meaning in a unique context in history, not as a timeless object but as cultural production.

***

In an earlier post I discussed yet another approach to teaching aesthetic reading that can sit comfortably within a curriculum of close reading. Where critical reading foregrounds the text as an aspect of its context at production and reception, where close reading foregrounds the structural unity and internal coherence of autonomous texts, reader response theory foregrounds the inner workings of reader consciousness and honors the relevance of now. Yes, Homer still speaks to students; let’s think about the ways in which Homer lives today. The reader is musician, the text is sheet music, the music as heard is the experience. Learning to read in such a manner that one actually makes music in the moment—this is reader response. For more please look at

***

The Common Core foregrounded an approach to reading instruction that asked more of reading teachers than attention to phonics, vocabulary, prior knowledge, comprehension, and metacognition, all of which center instruction on the interaction between a reader and a text. The Core insists that readers do something with a text beyond understanding it, but by drawing the analytical reader closer to the text, the Core pushes the responsive reader away. It is possible to design accommodations in a theory of instructional action that leads occasionally to an argumentative essay, occasionally to reader’s theater, occasionally to cultural and historical critique, to discussions of personal experiences, to simple book shares, to excursions into personal or creative writing.

https://time100.time.com/2013/04/18/time-100/slide/david-coleman/

https://web.uvic.ca/hrd/closereading/

https://www.heinemann.com/shared/onlineresources/e04693/noticenote_flyer.pdf

This is a tour de force and requires closer reading.

But first a thought on something it inspired.

Reading an Organic Chemistry text, one would think the meaning is in the text as straight forward as that can be, but no, all the meaning is in the outside context, and the sentences are mere breadcrumbs.

It is analytical outside the purported analytical text.

On the other hand, science fiction, said to be about the objectification of a scientific fact, is closer to poetry in that it creates an aesthetic experience the reader.can flow through and come out emotionally changed. Many times I have had to come down from that experience to realign with the current social structure. Teardrops of thought in this roiling vortex.