A wiry little boy with a crew cut, Dean’s rambunctious opening of the door to my small reading clinic announced his arrival with an unmistakable clang.

I’d fixed a bell to the door to alert me to visitors to the 1,000 sq. ft. building on Jefferson Street, previously a space housing an insurance agent. I had become a proprietor of a one-on-one tutoring service in Napa forty+ years ago. Dean was among my first clients.

His mother and first-grade teacher agreed that, except for his reading, he was ready for second grade. He was on track with math, he was smart and likable, he was open to learning. Of course, reading is an outsized part of the first grade curriculum.

The stigma of retention concerned his parents. He was popular, funny, an outgoing child, and nobody wanted to do harm. Still, his teacher knew two things: He would need help, and his family had limited resources. The daughter of a neighbor, a high school senior, tried to help him, but she soon threw in the towel. His angry, frustrated outbursts brought her to tears. Though it was a hardship Dean would get private tutoring.

English was Dean’s first language, according to his mother, but Spanish was spoken in his neighborhood and among a considerable portion of students in his school. Some of those children struggled to read English as well, the exclusive language of instruction, but Dean was in a league of his own. During intake assessment I asked Dean if there was anything about classroom reading that he liked.

Yes, he replied, he liked hearing his teacher read stories aloud to the class. She read stories every day after lunch. Sometimes she read stories in Spanish. In fact, he did well in listening comprehension at intake with material at a third grade level.

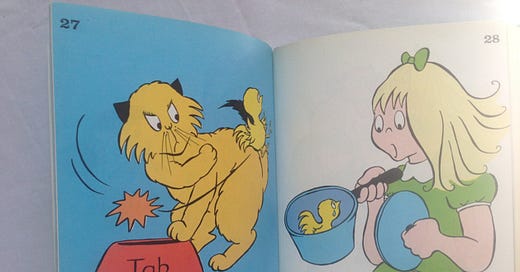

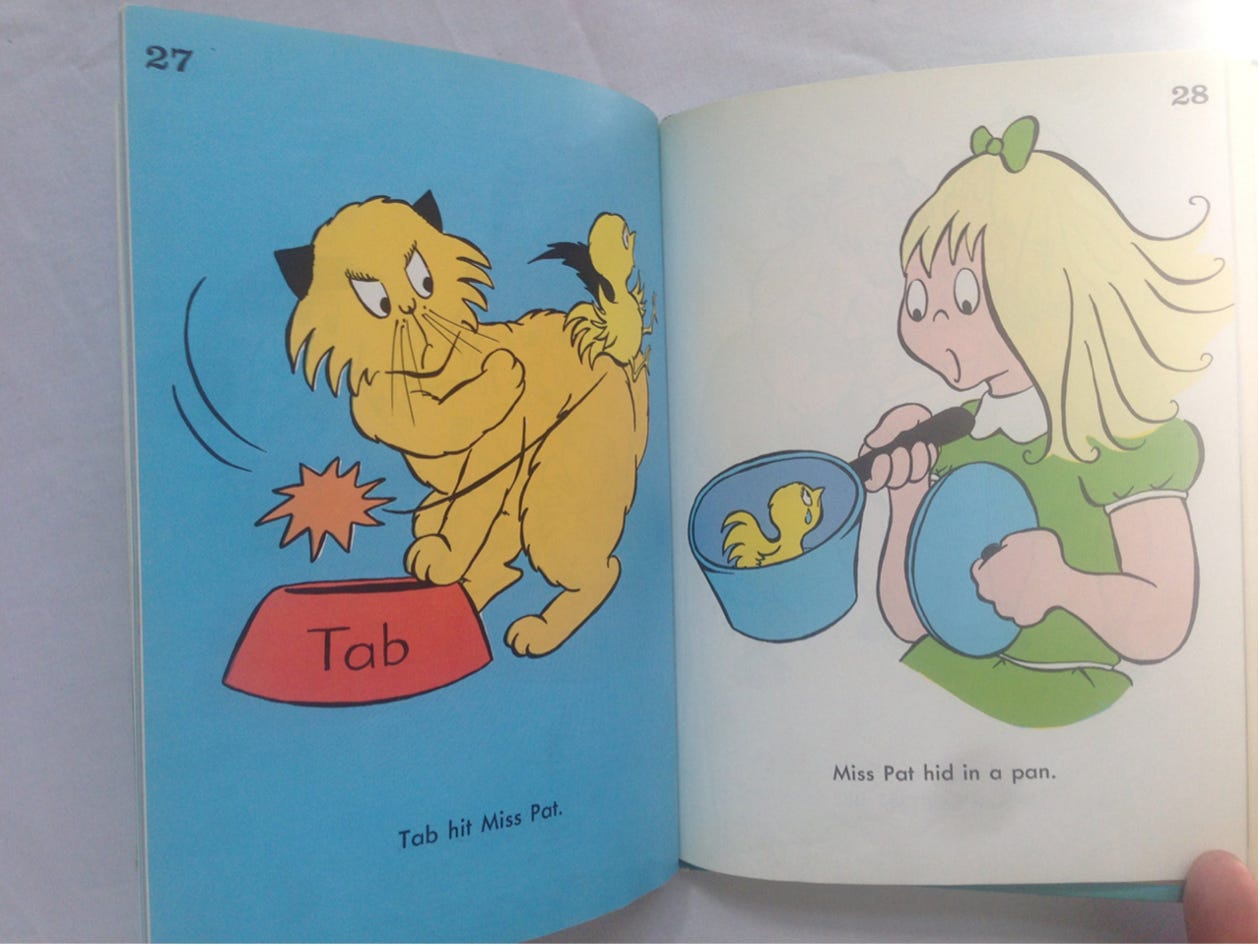

But his mood darkened when he was asked to read aloud himself from first grade material, especially phonetically regular material like the Sullivan readers1, popular instructional material for practicing phonics skills at the time. Kurt had several complete collections of these readers, and I ordered them for the Napa clinic.

Dean became surly when I asked him to read a passage like this:

Dean had automatic name recognition of upper and lower case letters, I found, though he had difficulty producing some shapes in writing. Like many children, he reversed lower case b and d.

He also instantly recognized several preprimer and primer level words from the Dolch list2. Word recognition in isolation on the Wide Range Achievement Test, measuring the full spectrum of grade levels from pre-K to something like 19th grade, was in the pre-K range, indicating that Dean was not retaining very common content words from day to day reading experience.

The New Gray Oral Fluency Test also placed him at early first grade, pre-primer level. His reading rate was extremely slow, he barked at words, fixated on initial letters, rejoiced upon stumbling onto a word known by sight, and he could not recall anything.

Dean was developing oral language skills and could use words in age appropriate ways in speaking and listening. He expected to understand and be understood in conversation.

But he did not expect print to make sense. His first year of school had taught him that reading was one word at a time, seeing a word, recognizing it or not, moving on to the next word. He was not melding words into ideas. For him reading had little to do with speech or making sense. It was a matter of calling out words.

I saw Dean twice a week for a year. My objective in working with him was first to instill in him the expectation that print would have meaning just as speech has meaning. I would put making sense first, word analysis second. I had read about the Language Experience Approach, an instructional approach with this idea framework, and it proved to be a good decision for Dean.3

To that end, when we worked on connected text at his instructional level, I read the passage aloud to him first as he followed along with his eyes, we talked about the overall meaning, and then we sounded out or broke apart single words used in the passage. Finally, Dean would read the passage aloud with considerable scaffolding.

Dean also needed work in decoding isolated words of the type described in Words Their Way4 to build his capacity to use phonics as a tool to unlock unfamiliar words. I worked with him to perceive and apply spelling patterns to decoding (single syllables with consonant-vowel-consonant spelling or ‘closed’ syllables, segmentation and blending—much of which tracked well for me given my background in descriptive linguistics).

Dean started each half hour session with me as a happy little boy. During the lesson he often showed signs of frustration, occasionally crying, always put through the wringer, but gradually he perceived that he was improving, and we worked out a deal where he could take a break if he felt a fit coming on. I showed him the notes and records I had been keeping as proof. He knew that I made these cryptic notes in his folder. After I explained to him how to read my squiggles, he wanted to see.

His mother sat in on lessons occasionally, especially early on. I wanted her to use the word cards and story cards I wrote for him during his lesson in sessions at home just as I had used them. I used methods I had learned from Kurt, the owner of the LA clinic, to generate the cards.

In hindsight, knowing what we know now about the role of auditory processing of phonological information, it’s clear to me that Dean absolutely needed someone dedicated to his idiosyncratic learning needs. I don’t know what became of him, but I do know that he left me with a foothold in literacy, though he still labored at it even with easy stuff.

When I think of Dean, I wish I had known more. He signifies for me the need for reading specialists trained in a professional knowledge base. Not all children need such a specialist, but those who do face a difficult road without attention.

Today, I wonder how my time with Dean would have changed if I had only known more. Fortunately, I understood the instructional affordances of the Language Experience Approach; I was reading about the cognitive revolution in reading theory, including the centrality of prior knowledge and vocabulary; and I had learned from Kurt an effective way to teach phonics.

But I had not yet learned about metacognition, the central executive function, the zone of proximal development. I knew nothing of the think aloud as a research, assessment, or instructional technique. Undoubtedly, I would have done much more modeling of thinking behaviors, and Dean would have been thinking aloud for me.

It did not occur to me to collaborate with his classroom teacher. I could have incorporated stories she read aloud in class into my interactions with him. I might have given her assessment information that could have informed her work with him. At a minimum I could have given her feedback on Dean’s emerging Spanish. I hope he developed both English and Spanish, but I was inert on that front.

One day I saw Dean for a final time. I don’t recall it, but him—I remember him clear as a bell. He was part of the reason I began to explore the topic of adult functional illiteracy. Over the next few years I located and interviewed several adults who had come out of the closet of shamed non-readers to get reading lessons at the Napa Library through a volunteer tutoring programs. I recorded these interviews. At some point I plan to post narratives of these interviews in the publication.

https://www.mothering.com/threads/anyone-remember-sullivan-programmed-reading-workbooks.1200778/

https://sightwords.com/sight-words/dolch/

https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED040025

https://www.amazon.com/Words-Their-Way-Vocabulary-Instruction/dp/0137035101/ref=nodl_?dplnkId=ad8736db-37c7-44c8-93db-bf5fe36d2671#