My English teacher in eighth grade taught her students to recognize what are now know as informal logical fallacies under the heading ‘propaganda.’ Glittering generalities, the band wagon technique, red herring, argumentum ad hominem, and my favorite, the straw man, whiling away the hours, conversing with the flowers.

Beware, she cautioned. Don’t be a fool. There are more, she said, but these five topped her list. Forearmed is forewarned.

With the exception of a six-week unit on syllogistic reasoning in a senior year course in rhetoric, high school passed without much in the way of explicit instruction in critical thinking.

***

I stumbled across Socrates, whose teaching method is renowned for its relentless interrogation exposing internal contradictions in arguments, in an intro to philosophy course at Illinois Valley Community College. His reward? A cup of hemlock.

I carried the marble image of Socrates in my memory from the picture in my textbook into my future as an unsettled blessing. He, I, and my English teacher were sympatico on pushing back against nonsense, but I saw writing as the doorway to immortality, and eternity as a place for me in the Dewey decimal system and a secure slot on a library shelf.

Yet Socrates warned against the dangers of writing.

Socrates wanted little to do with writing beyond its use as a memory aid, though he seems to have given in to a bit of Sappho. He preferred two or more live minds creating a critical fire to melt down faulty assumptions in real time. Writing gave both the first and last word to an absent writer. Half of the dyad is always missing, yin and yang infinitely apart.

This was the Greek philosopher who mentored the youth of Athens to question authoritarian rule, to question the supremacy of the gods, to turn the tables on oppression, to seek beyond understanding toward wisdom.

Socrates was passionate, if playful, about examining arguments, and he didn’t hold back his critical fire. It cost him his life. Later, I learned that Plato, his student, banned poets from Utopia. I could not figure this out for the longest time.

***

When is the optimum time to begin instruction in critical thinking? A franchise of preschools in Northern California posts a website with information about teaching CT at home and in their schools. Witness1:

Clarity and rationality would not be descriptors flying to my fingertips to describe early human thinking, but very young children are capable of making logical connections among ideas: If I say ‘please’ and ‘thank you,’ my parents smile. So please and thank you it is. The kicker is sentence two. Young children are capable of reflection—of course they are; learning is impossible without reflection, without bending backwards—but they must be encouraged, invited, rewarded, motivated to become active learners rather than passive recipients. Remind you of Socrates?

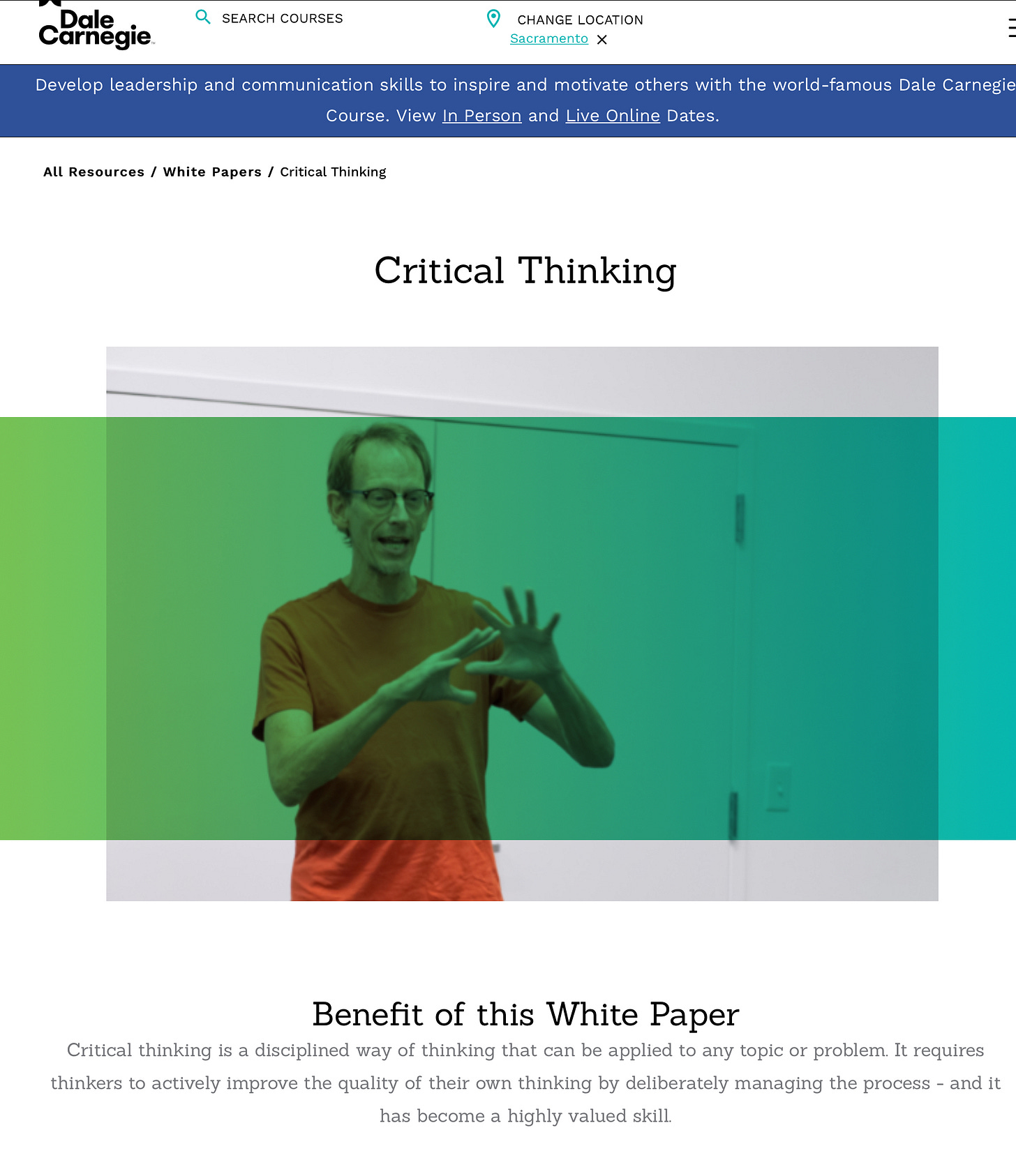

Adults, it seems, can shoulder CT all by themselves. Dale Carnegie, who taught us how to win friends and influence people, has jumped on the CT bandwagon, generously offering a White Paper on its website for anyone with the moxie to beef up their brain a bit. Perhaps now the motto is how to influence people and win friends? Witness2

Why should you supply your personal information and subscribe to DaleCarnegie.org in exchange for this Paper?

Read carefully the explanation of the benefit. Plus examine the photo of the man explaining something very complex with his hands, signs from an esoteric geometry of communication. Clearly, this is an act of inspiration and persuasion. Could that be me framed in green and white gesticulating so exotically? Download the paper. Jump on the bandwagon.

What are the benefits of the White Paper? Ask and ye shall not see. Sentence one: CT is a disciplined way…a disciplined way… ok. It keeps repeating the words. Nothing against discipline in moderation…. So about that White Paper. Sentence two: Hey, thinkers, get active, improve yourself, you can do it yourself, you don’t need me, you need my White Paper, manage the process… ok.

But what are the benefits of the White Paper? Do I read it and—voila? The Paper gives me an injection of CT juice? Will the paper do its thing if I speed read it?

I’m troubled—not by the White Paper. I haven’t even read it and offer no thoughts on it. What troubles me most is the assumption that critical thinking is somehow autonomous, a solitary force in consciousness. If you can read, which you can, and you want to improve your thinking—who doesn’t?—read this White Paper. The right answer awaits. Are you disciplined enough to do it? Are you really serious about it? Can you manage the process? Use your bootstraps.

Contrast this with the early childhood assumption of a caring, loving activity setting where parents consciously take up the stance of a CT mentor, a stance that could become a habit in their parenting.

The preschool website offers on the site with no questions, no subscription, no specious persuasion, a set of four activities easily and naturally done anywhere adults raise children. Witness:

When my daughter was around two years old, after she learned to name all of the letters in the alphabet puzzle she’d played with, this routine would have been fun to try.

Instead of hiding a toy, I could have hidden a letter and evoked or asked questions or given hints, two classic teacher moves in the zpd. Does the letter have two curved lines? Does the letter have one straight side? This letter sounds more like a bat than a cat…

***

One danger of writing, as Socrates pointed out, is this: Writing doesn’t answer questions. Ask one and the writing provides no more than what you already have. Writing arrives in your hand with an authoritarian aspect—often culturally or politically authorized as well.

Written texts as they face a reader offer a record of a monologue or a dialog, not a living dialog, a set of directions to assemble language thus and so in one’s consciousness—and then try to breath life into it. If the words say anything, they speak in your voice, and as Socrates told Phaedrus, they say the same thing repeatedly.

By all means, try the White Paper. I may have a look myself. I’m just not sure I want to subscribe to the website to get it.

***

Having worked at assessing CT with faculty from across the university curriculum informally and formally, I can attest that CT is on the radar in higher education.

My experience base for what I’m about to write comes from two sources: 1) my work as faculty university assessment coordinator at CSU Sacramento (2008-2011), and 2) my role as a contracted assessment consultant for the Academic Passport Project (2009-2014), a project of the Western Interstate Commission on Higher Education (WICHE).

In both jobs I rolled up my sleeves and got involved in nuts and bolts assessment issues and instructional strategies with faculty in the trenches at community colleges and universities.

At CSU Sacramento, like universities across the country with an interest in being accredited and thereby eligible to receive federal money, institutional assessment of student learning outcomes had been simmering on the back burner literally for decades.

Faculty weren’t excited about assessment. In my own department, I’d become known as the assessment guy, and I kept pretty quiet. The mainstream strategy had been to hunker down and ignore the pressure, to ban the “A” word.

In the 1990s, the nursing program at CSUS was among the first to face accreditation with program assessment of outcomes on the table. A sticking point was this: Separate programs could not be accredited unless they were housed in an accredited institution. Hence, a nursing professor became the first university assessment coordinator and received a token three units of released time credit from a teaching schedule of 12 units. By 2008 I became the so-called assessment czar with nine units with a dedicated office and a student assistant.

The drumbeat for evidence that students actually learn something from their four years in college grew louder. Arum and Roksa (2011) published their study of CT in American colleges and asserted that higher education was “academically adrift,” that students float through their college years with little thinking value added. I remember an assessment conference where these sociology professors were speaking. The size of the presentation room increased with three room changes to larger venues in the conference center so strong was the interest. Even then the halls outside the room were packed.

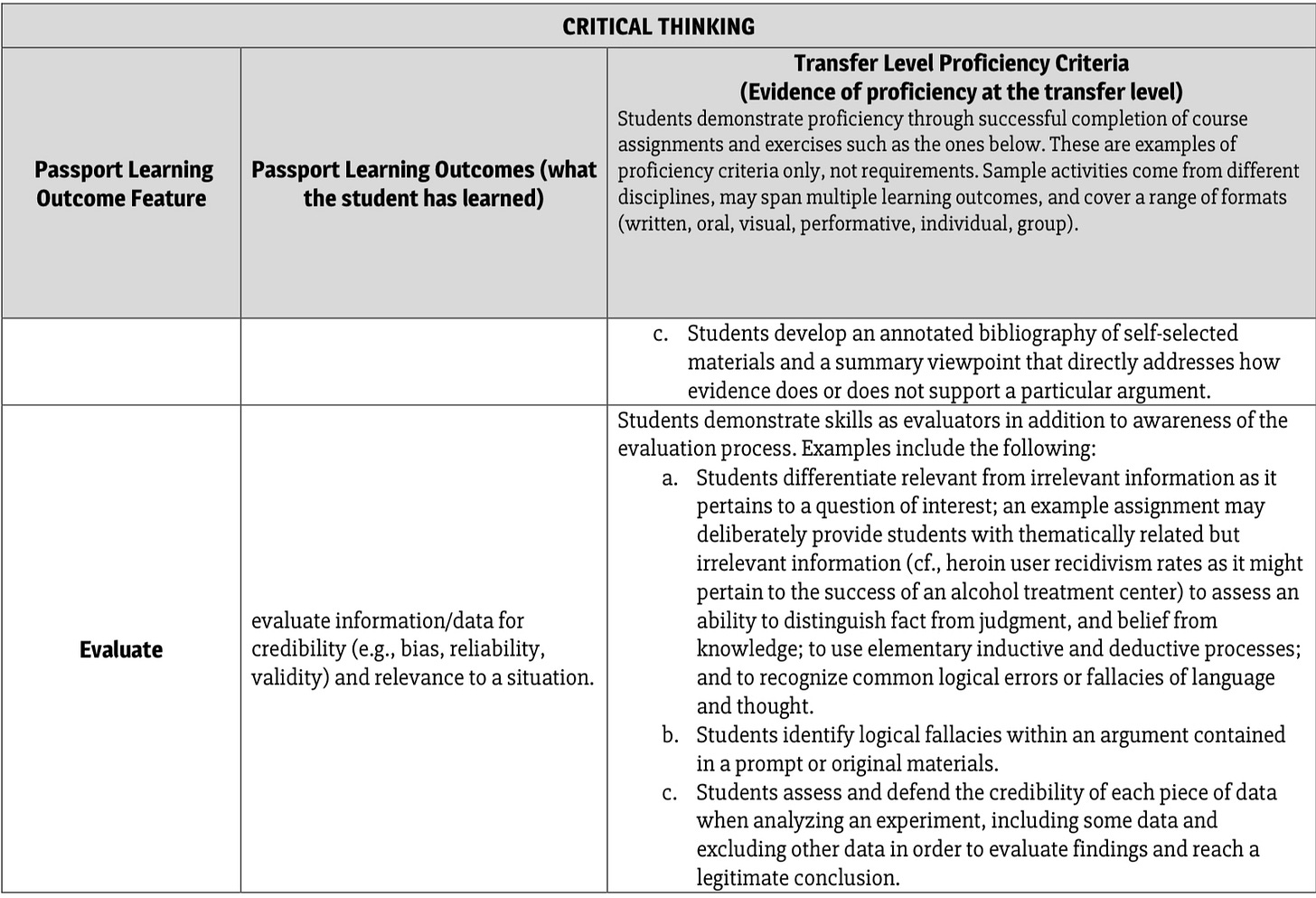

Since then, at least two large-scale projects to operationalize CT as a robust learning outcome for the baccalaureate degree have moved from proof of concept to implementation: the WICHE Academic Passport and AACU’s VALUE Rubric project nationwide. The following presents the Passport’s take on CT as it should be developed at the point of transfer from General Education to a baccalaureate degree program. Witness:

The importance of WICHE’s work on CT and on other learning outcomes derives from its roots in problem-solving on behalf of young people trapped in a transfer loop, losing credits, losing time, losing money—and from its method of development and its assumption of trust in faculty. A casual glance at this screenshot convinces readers that the language came from teachers, a valid assumption in that the focus of project resources was on bringing disciplinary and cross-disciplinary faculty groups together to discuss common, iconic assignment genres faculty actually use in community colleges to teach toward particular outcomes.

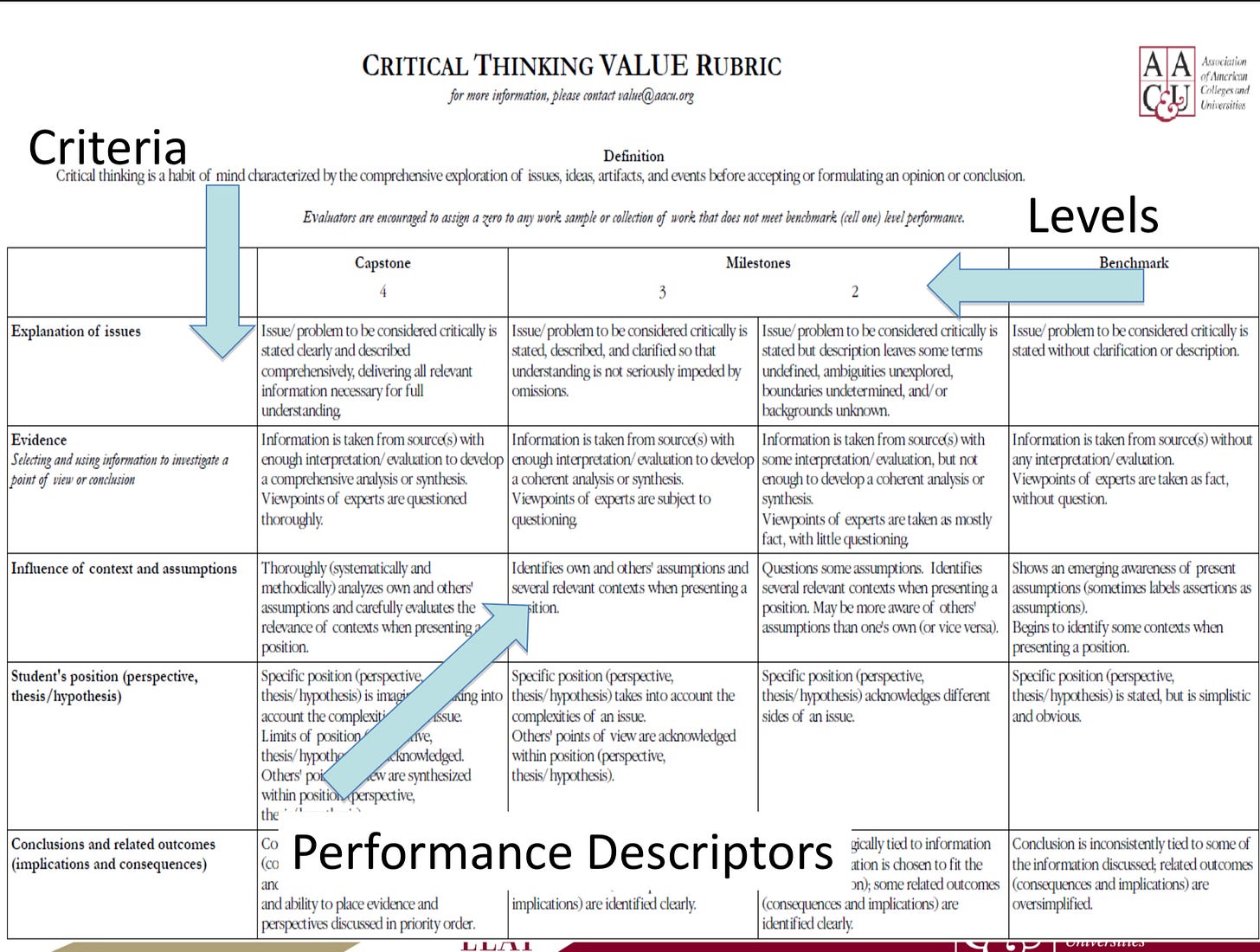

AACU paved the way for pulling together faculty groups as the genesis of a set of rubrics spelling out developmental levels for college students vis a vis fifteen learning outcomes. Each rubric was designed and written by faculty groups using a template provide by AACU. I participated in the group that wrote the VALUE rubric for “Reading.” If you check it out, you’ll see my friend Socrates in the framing language of the rubric. Here is how AACU sees critical thinking. Witness:

It would be hard to argue against such skills and inclinations forming a habit of mind and easy to envision university faculty working to promote it. Still, when higher education is asked to show evidence that students are actually developing CT, that the institution is not academically adrift, faculty often turn to writing as the source of evidence. Students who are competent writers leave evidentiary traces of critical thinking in their texts, so the thinking goes.

But researchers question the reliability and validity of assessing writing and critical thinking simultaneously—much as assessing reading through writing has been viewed with a touch of skepticism. Braun, Shavelson et al. (2020) described an assessment approach that doesn’t negate the use of literacy but opens the aperture. Witness:

“The framework is a product of an ongoing, collaborative effort, the International Performance Assessment of Learning (iPAL). The framework comprises four main aspects: (1) The storyline describes a carefully curated version of a complex, real-world situation. (2) The challenge frames the task to be accomplished (3). A portfolio of documents in a range of formats is drawn from multiple sources chosen to have specific characteristics. (4) The scoring rubric comprises a set of scales each linked to a facet of the construct.”3

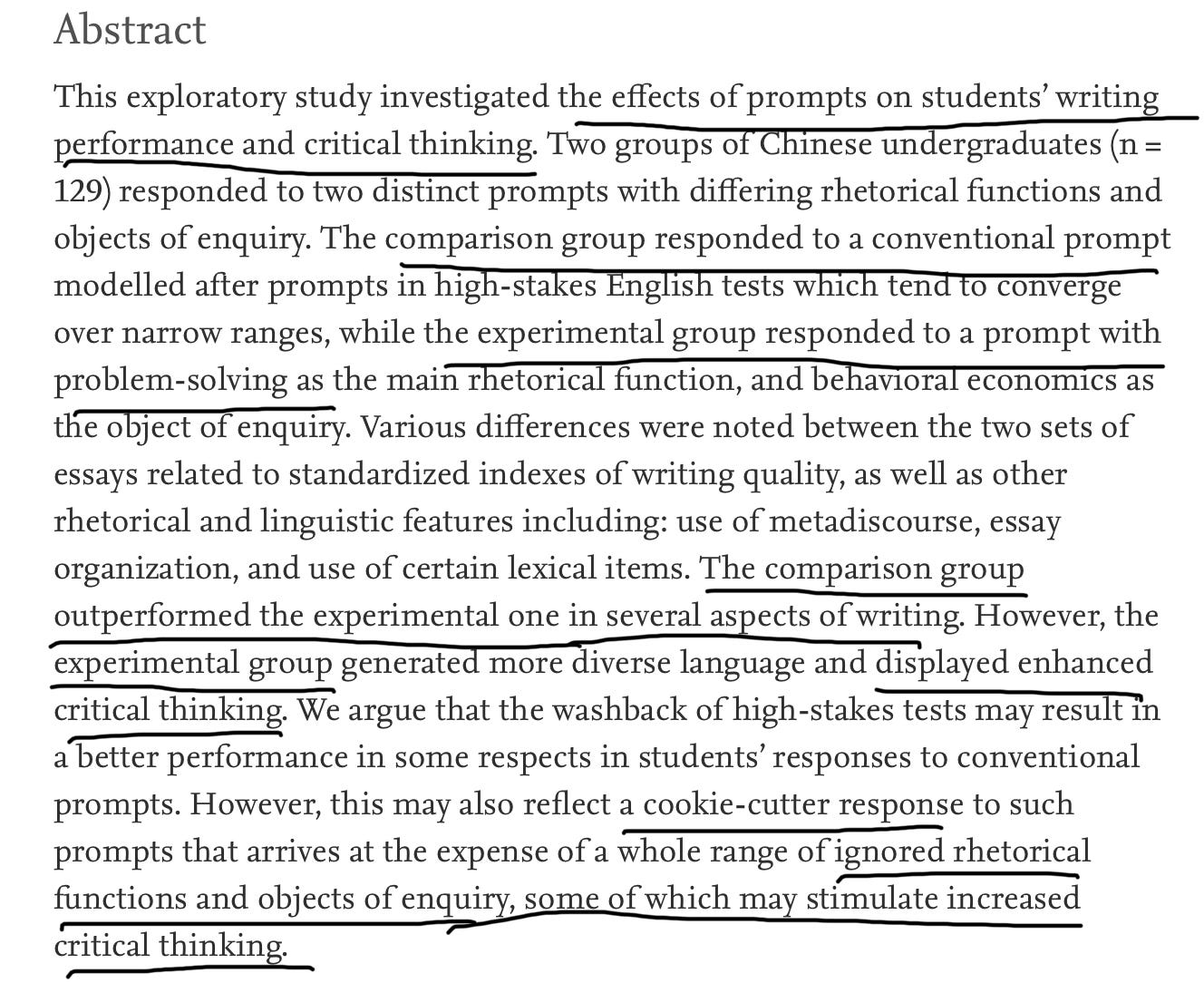

This approach is very different from collecting a portfolio of writings. The following abstract describes a study carried out in 2019 which underscores the need for a new centering of CT in higher ed apart from literacy. Witness4

At a minimum, this study distinguishes between generic writing assignments and specific assignments with CT infused. Critical thinking can be messy, full of dead ends, filled with hunches, definitely assisted via symbolic and technical tools and signs, provoked during literacy events (reading, writing, speaking, listening in concert). But isn’t it better if the writer keeps the clutter out of the polished text? How does one assess critical thinking in a product built for clarity, coherence, unity, and order, a product intentionally sweeping the mess under the rug?

***

In the California State University system, Critical Thinking is taught as a stand-alone course and as a baccalaureate degree requirement. CT as a separate course has no obvious disciplinary home, although this assertion would draw pushback from philosophy professors who lay claim to Logic, the master key to reasonable critical cognition. Mathematics professors also have a claim. In practice, each College with its constellation of disciplines determines the nature of critical thinking courses offered under its aegis—the course in the hands of a historian differs from the course in the hands of an anthropologist.

As assessment coordinator at CSU Sacramento, I once surveyed the entire faculty and asked them to rate each of fifteen learning outcomes spelled out by AACU in their VALUE rubrics as to the level of importance each held for their instructional behaviors on a scale of 1-5, 1 being “none,” 5 being “strong.” I asked respondents to self-identify as “Lower Division” or “Upper Division” for purposes of analysis.

The most potent outcome driving instruction across the board was Critical Thinking weighing in 4.5ish depending on the discipline with very little variability. Writing was in the top tier. By comparison Creative Thinking weighed in 2.ish with considerable variability. Ethical Reasoning was all over the map, generally of weak importance.

With roughly 1,300 respondents I was able to defend to myself analytically grouping survey responses by program and thereby present measures of central tendency to small groups of interested faculty and to look at distributions on the fly. Most things related to institutional assessment were voluntary with the exception of departmental reporting to the Office of Academic Assessment using the institutional template.

Discussions were fruitful and interesting: So how much opportunity is there to discuss mathematics in an upper-division course in Victorian literature? What about frequency word counts? Semantic bubbling? Why do engineers devalue ethical reasoning? Do they, really? What about visualizing? Art Education and Graphic Design wanted to know where visualizing is represented?

These discussions led me to conclude that discrete outcomes fitting comfortably in a box or a list don’t present as discrete in practice. Instead of functioning like a color wheel on a Christmas tree with slow moving baths of single colors, each outcome flashes as red, then green, then orange, outcomes present as colored shards in a kaleidoscope, taking on a gestalt only to reassemble at the next bump or twist. The master teacher who really knows a subject can do masterful things with an outcome kaleidoscope.

Learning outcomes double up, bend, overlap, and reposition themselves in the ever changing landscape of a teacher’s consciousness trained on learners in action. It is here attention needs to focus, not on fidelity to a script. My survey was but a crude tool where an ethnography was needed, better yet a phenomenological analysis.

I think critically; therefore, I am better able to understand and act. I can make wise decisions. I can problem-solve. I can listen and speak, write and read better. Best of all, I can be taught, and I can learn. I can become.

https://www.kids-konnect.com/blog/critical-thinking-skills-for-preschoolers-4-fun-activities-to-try-at-home#:~:text=For%20preschoolers%2C%20critical%20thinking%20involves,than%20passive%20recipients%20of%20information.

https://www.dalecarnegie.com/en/resources/critical-thinking-the-essential-skill-for-navigating-the-future?utm_source=google&utm_medium=cpc&utm_campaign=TCPA%20-%20Critical%20Thinking&utm_content=Specialization%20-%20Critical%20Thinking&utm_term=learn%20critical%20thinking&skai_kpid=go_cmp-12902702630_adg-124547807267_ad-518129132157_kwd-379606810496_dev-t_ext-_sig-EAIaIQobChMIu6Tp6PrQ-gIVVRitBh0ymAe7EAAYAyAAEgIb3fD_BwE&gclid=EAIaIQobChMIu6Tp6PrQ-gIVVRitBh0ymAe7EAAYAyAAEgIb3fD_BwE

https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/feduc.2020.00156/full

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S1075293518300813