Charles Ruff1 sat back in his chair in the conference room off the library, staring at a wall, concerned about the upcoming English department meeting. Someone had decorated the windows with cutouts of pumpkins and ears of corn. A bowl of wrapped caramels on the conference table completed the Halloween theme.

The agenda had one item: AI.

District administration had been unable to act on an AI policy to date, and already eight weeks of the new school year had evaporated. Chat bots erupted during the 2023-2024 academic year in epidemic proportions, rattling management cages like nothing ever had before during the wackiest of his twenty-nine years teaching at MidWest Public Prep High2.

Principal Harrison had abruptly changed the speaker for the first professional development day in late October, 2024. The canceled speaker was to talk about projected changes in AP curriculum and tests over the coming five to seven years, a topic of general interest—or better be, Harrison thought. Instead, department chairs were told to hold morning department meetings to be followed by an afternoon faculty meeting in the auditorium chaired by the Superintendent.

The issue was clear: To be or not to be. To forbid or to embrace bots like ChatGPT as a teaching and learning tool. After their meetings, after a catered lunch, each department chair would report on their decision subsequent to their vote to the whole faculty.

*****

Cynthia, the English Department chair, brought the meeting to order and spent several minutes reviewing the genesis of today’s upcoming events. Principal Harrison had called an impromptu chairs meeting in which she described a firestorm of controversy engulfing the Board and charged the chairs with communicating the urgency of the moment.

MidWest Prep High, a selective magnet school located in a sprawling suburban district on the outskirts of a densely populated and heavily minority urban core under a state ordered district takeover, served a community of established affluent neighborhoods with stately compounds built in earlier centuries surrounded by a sea of working class white people and minorities living in cookie cutter houses. Beyond the suburbs miles and miles of land was owned by agribusiness producing much of the wealth of the area.

“Principal Harrison explained the plight of the Board as follows,” Cynthia was saying. “We understand that our students come from the heart of America—now these words are hers, not mine. I think she is asking us to think about the spectrum we teach. We do get homeless students, right?”

“Are those Harrison’s words, too? Cynthia! Come on,” Harold interrupted, the cynic who probably should be in another line of work. “This school once accepted one homeless student. For God’s sake, next we’ll bill ourselves as a sanctuary school for AP prep.”

The department meeting devolved from the structure Cynthia had envisioned into a freewheeling chaos, a microcosm of the turmoil engulfing MidWest Prep High. Never had Charles Ruff heard such stinging, veiled, oblique references questioning the academic integrity of colleagues on the record. Favoring AI was tantamount to favoring cheating.

"I must put a stop this ranting and get us back to the issue. We can't—I can’t just ignore AI," Sarah, a veteran teacher of 20 years, insisted in her most teacherly voice. “I know that sounds strange coming from me. I’ve tried desperately to ignore it. I hate it. It makes me want to quit teaching.”

Highly respected as an AP Literature and Composition teacher shouldering a massive workload each semester, Sarah secretly feared that AI would destroy her reputation. The bread and butter of her homework and grading consisted of multiple-choice exercises and timed writings styled after the AP exam.

“You can do multiple-choice with ChatGPT,” Mark, the newest and youngest English teacher, said.

“That’s interesting,” Sarah responded. “I didn’t know that.”

“I’m using multiple-choice quizzes in class myself to keep them on their toes,” Mark said. “AI is great because it can discuss why their choice was right or wrong. They can try to rewrite the question if they believe the question was bad. We read a short passage, take a quiz, I give them the answers, they get three-five minutes alone with the bot, we talk about the quiz. They like it.”

“I usually review the exercises and explain the reasoning,” Sarah said, concerned.

"Sarah, Sarah, Sarah,” moaned Mary, the eldest teacher. “These AI things or robots, or whatever the hell they are, are going to make our jobs obsolete!" Mary was ready. “I’m personally counting the days to retirement.”

“Don’t,” Harold said. “Mary, you have irreplaceable magic.”

“Aw, that is sweet, Harold,” Sarah said. “Are you feeling all right?”

"They’re just computers, people," chimed in Mark. “Mary, if you don’t want to use them right now, I think that’s fine. But I would encourage you to at least try to do something with ChatGPT. We could do it together.”

Mary took umbrage.

“I’m really not interested, Mark. When you have taught as long as I have, then I might ask for your help. I have important things to attend to,” she said. “I’ll be in my room if needed. Cynthia, my vote is no.”

She rose, crossing her fingers to keep vampires away as she left the room.

Charles sighed. It was like this everywhere in the school. The 2024-25 academic year had barely begun, and already the specter of machines corrupting the human race loomed large, an existential crisis of Nietzschean magnitude beyond good and evil.

*****

After the English department vote, 12 to forbid AI, 8 to allow its use, and 1 abstention, the meeting adjourned in spits and sputters, fracturing into animated pairs in discussions. In the hallway Charles caught snippets of fraught conversations as Department chairs coming from their own meetings huddled with worried expressions. Administrators hurried past with furrowed brows, and even the usually unflappable Principal Harrison looked stressed.

"The Superintendent is breathing down my neck," Charles overheard her mutter to her one of her Vice Principals. An impressive African-American woman of great charisma and depth, Margaret Harrison expected to find herself alone in the hot seat when the point of no return finally arrived. Superintendent Johnson appeared poised to make it so.

To be—or not to be.

"I just got off the phone. The Superintendent is on her way. She wants a faculty vote. She will not change her mind. She calls us the flagship campus. Do you want to be the first to tell her this ship is taking on water? If we are leading the charge with respect to AI, I do not want to see who is at the end of the line. How can we make an AI policy when we can barely talk together about it with open minds?"

The Superintendent was expected any moment.

As the troops filtered into the auditorium, Charles Ruff met up with Mark and stopped to catch up after the vote. They had been talking together a great deal about chatbots, each experimenting. Mary, the teacher who walked out of the department meeting, came over to them. Charles and Mark expressed their delight at seeing her.

“I don’t want to retire,” she said. “Mark, would you mind showing me what you are doing with multiple choice exercises and AI. I have to admit it sounded intriguing.”

******

As the faculty assembled in the auditorium for their second meeting of the day, they sat together in departmental formations. The Department of Physical Education sat in the section farthest from the stage, awash in boredom, oblivious to the depth of fear among many of the AP teachers. Charles would have loved to have been a fly on the wall at their department meeting.

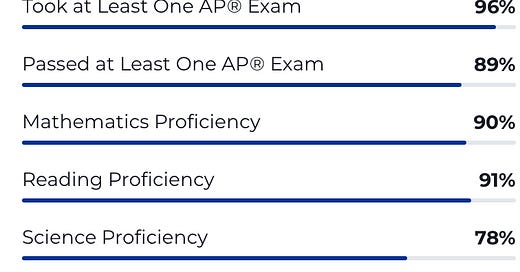

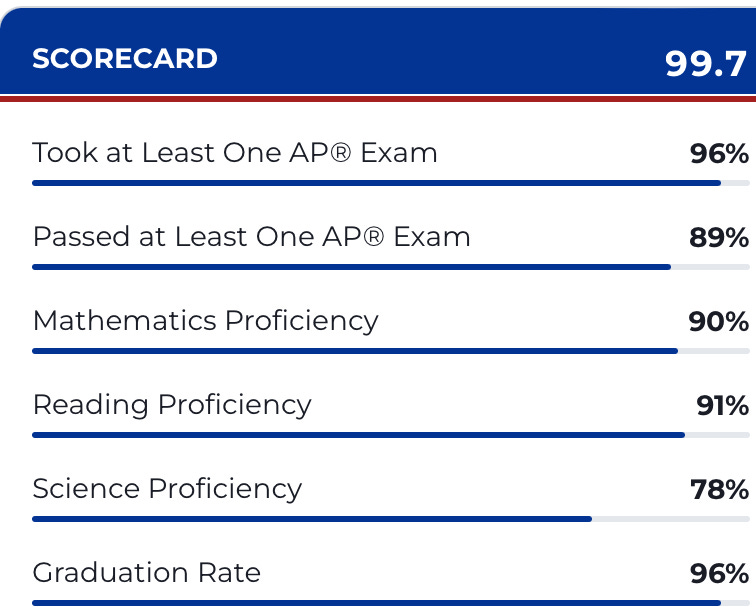

Superintendent Johnson spoke first, her mellifluous and calming voice lowered the temperature. She first congratulated MidWest Prep for last year’s scores on AP exams. Consistently ranking among the top five on a national scoreboard, the school brought fame and prestige to the district, not just for its AP program, but for its standardized test scores.

She spoke again about a flagship campus taking the district in the right direction during this time of risks “not just for our students and our schools, but for the future of humanity.” The AI policy MidWest developed here would become district policy by edict of the Board.

“God help us,” thought Charles Ruff.

*****

After the Principal, the school technology coordinator spoke.

“Good afternoon. Thanks for giving me the microphone, Principal Harrison. I just want to make you aware of what I can and can’t do for you. I am not a teacher at this school. I don’t have the background or experience to comment on instruction. But I am keeping up as best I can with the rapidly expanding AI resources coming online. If you help me understand how you want to use AI, I can suggest some specific products. I understand why you might decide not to use AI in classrooms for this one year, I also understand the speed of innovation. Whatever you decide I want to help. Thanks again.”

Superintendent Johnson approached the podium.

"I know there's been a lot of strong feelings about AI," the Superintendent said, her voice steady despite the anxiety in the room. "We're here to address those concerns and find a path forward, and I’m asking for your help. Each of your departments has taken a vote, yes or no, allow AI or forbid AI—just for this year, you understand. We will tally the votes and make our decisions, but before we do, I want us to listen to each department chair report the vote and provide the arguments for and against a ban. Then we will take a secret vote, one vote for each teacher. Principal Harrison will tally the votes, and we will have our answer—for this year. Does anyone have a comment?”

“Just a question.” A tall man dressed in blue jeans and a flannel shirt approached the microphone in the middle of the room. “To clarify, are you saying this vote will set AI policy for the entire district. As you know, we have hundreds of schools.”

“The vote we get will determine policy not just for you at MidWest Prep High, but for the entire district,” the Superintendent said. “We at district headquarters are well aware that this decision is temporary. The technology is here. Teachers will have to learn to teach with it even if it means fundamental change in curriculum and pedagogy. This vote is really about invoking a pause for one year.”

“We in the Agriculture Department have serious questions about what happens to our curriculum if you decide to prohibit AI,” he said. “I’m not sure we’re talking about the same concept.”

“Your department voted?” she asked.

“We tried to,” he answered. “Not one of my teachers could spell out a definition for AI.”

“Let’s begin with the Agriculture Department,” Superintendent Johnson said. “Do you mind, Mr. —…”

.“Thomas Jaynes speaking for Agriculture, Superintendent Johnson,” he said. “Well, as I said, my teachers weren’t entirely clear what kind of AI you want to ban. That being said, we tried to vote based on how we teach with AI. We have used an AI model called CropSim AI to model crop growth for several years. As the climate changes, our students have to learn to understand crop growth at field scale. It’s involved so I’ll give you an example. Suppose a farmer wanted to predict corn growth using predicted rainfall data, seasonal data, soil conditions, type of fertilizer, and more. CropSim is just one AI tools our students use to address crop yield problems. So we want to allow AI. Fact is we’re not doing our job if we stop teaching it. We also want to point out our work with the Science department. A lot of the content our students need is taught in depth in Science. They may want to touch on that.”

The auditorium was silent.

“Thank you, Mr. Jaynes,” Superintendent Johnson said. “This is important information. Well, you’ve piqued my interest. Let’s hear from Science unless another department chair wants to speak now.”

*****

Rita Smitherman, a botanist chairing Science, walked to the microphone.

“Thank you, Superintendent Johnson,” Rita said. “I’ll begin with another example of our collaboration with the Ag department. Farmers who produce livestock have to have scientific methods to monitor livestock health. We have worked a schedule so that several of our courses are offered to students who also co-enrolled in Ag classes where they do internships on a farm. Applying conceptual understanding from a Science module on the vital organs and natural behaviors of cattle and pigs, for example, our students analyze data from AI-powered sensors already installed in barnyards that track animal behavior, feeding patterns, water consumption, and vital signs.”

“Incredible,” said the Superintendent. “It’s becoming clear to me that we are really talking about an issue far more complex than cheating. To do your work as Science teachers collaborating with the Ag department, you can’t forbid AI. AI is already in barnyards, as you say. Do I understand correctly?”

“Absolutely. Science department also couldn’t vote for the same reason the Ag teachers couldn’t. If the district bans AI from the curriculum, one of the certificate programs we participate in with Ag through the local agriculture commission would have to stop. If I may, Superintendent, I want to speak to a process issue. How we as a school go about making this decision will influence our coherence and direction for years. May I use some time to explain?”

Charles and everyone else in the auditorium turned to look at the Science department, huddled together. Spontaneously, these teachers exploded in a round of applause. Rita turned from the microphone and gestured to them to quiet down, and they did.

She explained how and why the Science faculty still felt betrayed by the school eleven years earlier in 2013 during an earlier cataclysmic period. That was the year of Common Core. As the fickle wheel of fortune turned, the Core was being implemented exactly when Science teachers were being tasked with implementing the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), an ambitious project bringing science from textbooks into the real world.

Seeds of betrayal were planted in 2013. Developed through a collaborative, state-led process, the National Research Council's A Framework for K-12 Science Education was the basis for the final version of the NGSS released in April 2013, with many states beginning implementation 2014. Unlike previous Science standards, which were content centered, the NGSS integrated three dimensions of Science that put content as a substrate—disciplinary core ideas, science and engineering practices, and crosscutting concepts—aiming to improve disciplinary coherence and depth for students through an experiential approach. Curricular collaborations with Ag, with Fine Arts, with Business—these innovations happened because of NGSS.

“Our science teachers, for example, and our students are laser focused on climate change,” Rita said. “Of course, climate study requires expertise in basic science and advanced mathematics, but to deeply understand change, students need expertise in other areas. Our Earth and Human Activities standard requires integration of geography, chemistry, engineering, and more with history, economics, and sociology.”

Science had been through the reform wringer before. Demands of implementation of Common Core in 2013, followed immediately by the Next Generation Science Standards in 2014, forced the department to withdraw from the frenzy of Common Core. NGSS took all of the teachers’ time and energy, yet nobody seemed to care. Every meeting, every professional development opportunity, every retreat and celebration to let off steam and reconnect as humans—it was all about reading and writing. Yes, Science uses reading and writing, but Science teachers have only so much bandwidth.

Nobody knew. Nobody cared. It was a lonely time which forged powerful collegial commitments among the teachers, most of whom choose to remain at MidWest Prep.

*****

Dr. Mathew, the newly minted chair of the Math department, strode confidently to the microphone, a bemused smile playing on his lips. He had been a teacher in the department for ten years and had finished his doctorate, doing his research in math classrooms at MidWest Public Prep High.

“Hello, everyone. Welcome to our school, Superintendent Johnson. Let me ask one question, and I apologize in advance if it lands a little snarky. How do you plan to defend us from becoming a scapegoat if you make a districtwide decision based on what we have to say? There are hundreds of other schools, as we all know.”

“I appreciate your forthrightness,” Superintendent Johnson said. “We didn’t come here to create a scapegoat. We came here to draw on your expertise as a resource. Dr. Mathew, you are aware that this school gets the highest scores on state required tests? That your AP profile is a national model?”

“And you are aware, Superintendent, that our school is among the most highly selective public schools in the nation? If every public school could accept choice students and reject potentially challenging students, I suspect we might have some competition.”

“I see,” said Johnson. “But you must accept at least 15% of applicants from low income areas, and you must have numbers proportional with diversity standards. These restrictions were designed to retain your public school ethos while performing like a private school.”

“Well, even poor and minority students undergo critical scrutiny to get accepted here,” he said.

“And we all benefit from it.” Johnson smiled.

A chatter arose throughout the assembly of educators.

"With all due respect," Mathew said, his voice cutting through the noise, "Even if this faculty is respected for its scores and alumni, I think you’re asking a group of Luddites to determine the district’s willingness to continue supporting the evolution of technology in society.”

A hush fell over the room. Principal Harrison's eyes widened.

"Could you clarify your statement for me?" Superintendent Johnson asked, either genuinely confused or buying time to diffuse the situation.

Dr. Mathew smirked. "A Luddite, Superintendent, is someone who thinks the abacus is cutting-edge technology. Someone who believes the pinnacle of instructional innovation was a piece of chalk."

His words hung in the air for a moment before the room erupted again, this time in indignant protest.

"Dr. Mathew," Principal Harrison's voice cut through the noise, steel in her tone. "There are strategies other than ridicule you might consider."

The young department chair had the grace to look chastened, but only for a moment. "This group should understand the source of their fears," he insisted. "Even if it turns out natural language models do work against our traditional evaluation methods, the toothpaste is out of the tube, folks.”

Mathew provoked Charles and others to think of the bigger picture. MidWest Prep High's national ranking had been slipping a rank of two, particularly in Science Proficiency. Standardized pressure to improve on standardized measures, and now this AI curveball—a simple dichotomous decision to stick collective heads in the sand seemed inappropriate.

The English department chair spoke briefly. She summarized the group’s discussion and reported the deep divisions in the department.

“Our subject area may be the least prepared to deal with AI of all of you,” Cynthia offered for the good of the whole. As I listened to all of you, my eyes have been opened to the significance of this moment. Though we voted nay on AI as a group, we do have teachers already using chatbots in their teaching. In my mind we voted on a false choice. We may desire to keep our discipline purely human, a sentiment I agree with. But since we can’t, I have an alternative suggestion. Give us two weeks, Superintendent Johnson. Instead of asking us for our recommendation yes or no, let us ask teachers who understand more about AI to come up with options for structuring professional development in practical and pragmatic strategies for teaching with instead of against AI.”

*****

Charles found himself back in the conference room where the day had begun. The Halloween decorations seemed almost sardonically trivial now, given the mask that came off during the discussions in the auditorium.

He picked up a caramel from the bowl, unwrapping it thoughtfully. "To be or not to be," he murmured, echoing the question that had seemed so clear-cut this morning. Now, the simplicity of that binary choice felt naïve.

As he savored the sweet, careful not to dislodge a crown, he realized that they weren't just deciding whether to use AI or not. They were reimagining what education could be in an AI-integrated world. The real question wasn't about banning or embracing AI—it was about how to evolve alongside it, how to use it to enhance rather than replace human intellect and creativity.

Charles smiled, tossing the wrapper into the bin. Tomorrow would bring challenges, but also possibilities. And for the first time in a long time, since the debacle of No Child Left Behind and the craziness of Common Core implementation, he couldn't wait to see what the future of education might hold. This time there was no external pressure to teach a better way. The onward pressure of human innovation brought on this moment. He had a feeling that the ground at MidWest Prep Public High School had shifted.

All characters in this narrative and the events of the day are purely fictional and intended to represent various opinions about teaching and AI. Charles and other important characters are composites of real educators I have known. My intention is to dramatize how issues surrounding natural language models as they penetrate AP curriculums and the common core curriculum range from academic commitment to philosophy of teaching to professional obligations to personal identities. Solving the problems of AI will require a thoughtful focus on disciplines, disciplinary standards, and teachers’ theories of teaching and learning to find ways to teach students how to use AI to learn and to recognize and resist AI to cut corners and cheat. An aside: I don’t believe teachers have ever faced a problem so multifaceted yet so clear cut.

Midwest Public Prep High is fictional. However, a number of high-performing public high schools exist with stellar track records of placing graduates in selective universities. Thomas Jefferson High School for Science and Technology (Alexandria, Virginia), often referred to as "TJ," for example, is a magnet school consistently ranked as one of the best public high schools in the United States. It's known for its rigorous STEM curriculum and high placement rates at prestigious universities. Stuyvesant High School (New York City, New York), a specialized high school in Manhattan, is renowned for its competitive admissions process and exceptional academic outcomes. It regularly sends graduates to Ivy League universities and other top-tier institutions. Whitney High School (Cerritos, California) is a small magnet school in Southern California with a reputation for academic excellence and also ranks among the top public high schools nationally. It boasts impressive college acceptance rates to selective universities. Getting admitted to these and similar schools often mimics applications to college. However, at least one of these schools has dropped the requirement for standardized test scores and has pivoted to a holistic admissions process in order to increase diversity. This change is undergoing litigation.