“In November 2019, the California Health and Human Services Agency…develop[ed] a Master Plan for Early Learning and Care to…put into action…recommendations and research about the benefits of quality early learning and care. The team…address[ed] five…areas within California’s early learning and care system: access, quality, universal preschool, facilities, and financing.”1

Early Childhood Education (ECE) is getting well deserved attention in the most progressive state in the union with the world’s sixth largest economy in the hands of liberal politicians. The State Department of Education is clear about the long-standing purpose of ECE: to provide care for young children while parents work.2 But deeper understanding of the role of caregiving in fostering academic competence that shows up much later in schooling has reshaped considerations. Funding remains a potent issue, but it is joined now by quality concerns. Indeed, at the federal and at other state levels, policy makers are acting on the science regarding just how crucial the first five years are in shaping the life trajectory of the human being for better or worse. Was it B.F. Skinner, George Bernard Shaw, or William Wordsworth who said “Give me the child and I’ll give you the man”?

California has long considered extending the floor of public school to all children while other states were making incremental progress along the same path—Illinois, for example, began in the late 1990s to explore ECE as a way to improve bilingual education. In 2004 the Packard Foundation published a policy brief reporting a projected cost for running taxpayer supported quality universal preschools beginning at four years old. The analysis was based on various earlier proposals in California, including the Superintendent’s Universal Preschool Task Force in 1998, the School Readiness Workgroup for the Master Plan for Education in 2002, and the First 5 California Commission on Children and Families in 2003.3

The cost of universal preschool is a sticking point in any cost-benefit analysis. The federal government began funding Head Start and Early Head Start programs for zero-to-five year olds fifty years ago through a federal-to-local grant program with facilities administered by the states. From the start there was motivation not just to feed and shelter children in poverty while parents or guardians tried to work a job, but to care for developing young learners. As things worked out, Head Start and Early Head Start facilities nationwide are center-based. Eligibility to attend a Head Start center requires that a family is living below the poverty line:4

A national will to build a whole societal capacity to provide more than physical care for some 23 million children five years and younger has been galvanizing, perhaps because of the Biden administration’s putting quality childcare in the spotlight, perhaps out of the horror of COVID. Still, as ECE watchers have noted, efforts are legislatively incoherent (36 different targeted federal pots of money are currently available to help parents and children)5.

There is now a need for a philanthropic foundation to gather together our best human sociological imaginations in a room to dream up quality options to set the stage for human autobiographies unfolding from birth to death in a healthy and sane historical formation that keeps the future bright for the have-nots as well as the haves.

California has a Master Plan with funding linked to key parts of existing Human Resources and facilities, a bottom line threshold. The advance comes in the commitment to not just caring, but learning. From our admittedly narrow perspective, faculty like me teaching in reading specialist credential programs in the California State University system in the late 1990s thought about universal preschool as the most promising way to reset the debate about early reading that has roiled schools forever. Poor and marginalized children show up in kindergarten with less language and experiential development than privileged children. Phonics will not change that.

Phonics first, fast, and furious would be unnecessary and even unthinkable in a world that changed how children present in kindergarten. Children with opportunities to participate in rich language and emergent literacy experiences, building requisite tacit knowledge of language subsystem functions informally over many months in playful, responsive, professional settings—these children wouldn’t need scripted instruction. For reading faculty thirty years ago it seemed like an impossible dream even in California.

Unfortunately but predictably given the stultifying effect of conservative thought leaders who seem to believe that all babies are born with a strong pair of boot straps, some factory model red flags are planted in the California plans that could limit the potential impact as the implementation phase unfolds. I hope I’m wrong, but I’ve seen these flags before. Sarason (1992) is right. Reform failure is predictable if the reform is based on a myth of putting children first. Children actually have to come first. It’s one thing to make a plan based on state-of-the-art recommendations. It’s another thing to “put [the] plan” into action. When the plan calls for precision observational tools but relies on clunky standardized tools to hold everyone accountable, when troubling assumptions that serve adults but not necessarily children tilt the scales away from favoring children, things likely won’t work out as planned.

Although progress is possible in the offing if in access alone, don’t be surprised when the “one step back” shows up in quality. Twenty years from now our incoming class of teachers may be back to square one in making public school the great equalizer in the lives of poor and marginalized children. The same standardized test scores, the same crude measures of learning that drive public education today may not budge if interactions between teachers and young individuals are less than high quality not just on one day, but on every day. High quality individual interactions between adults and children ought to be the goal of the system, but that seems peripheral in a plan set up to serve children in large groups a la assembly lines.

*****

The Master Plan takes the issue of access to quality service seriously in practical terms like a sliding fee schedule for families; increased public funding to increase pay for teachers; creation of teaching standards useful to ECE teacher preparation programs at universities; and a credential ladder certifying assistant teachers, teachers, master teachers, and administrators on par with K12 policies and practices. Some of these pieces are already implemented in some states.

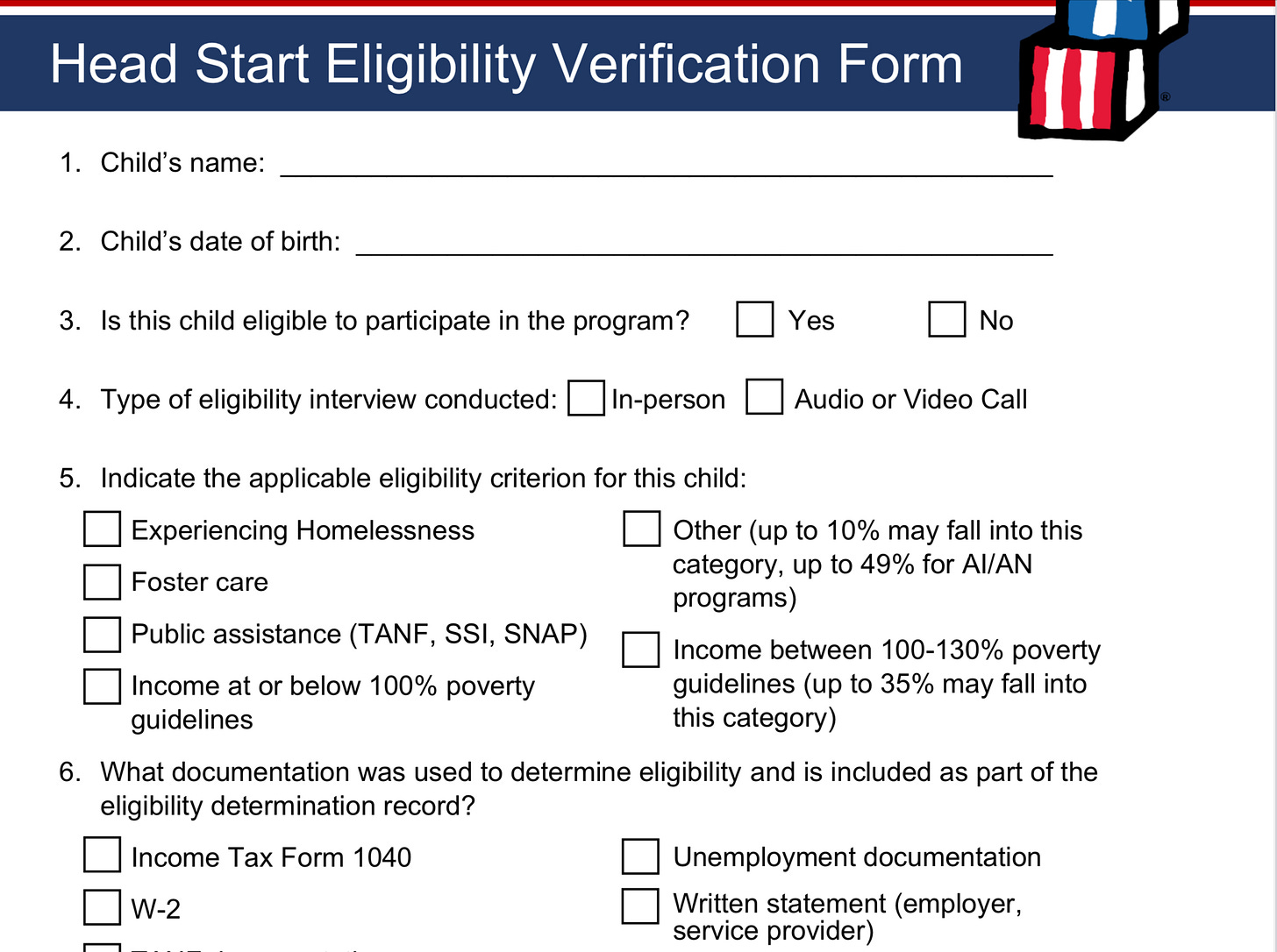

Nationally, the norm for early childhood workers requires them to have completed education beyond high school. The following graphic taken from a 2021 fiscal report available on the Head Start website depicts levels of preparation:

Licensing requirements in general require caregivers to take and pass tests, usually multiple choice, assessing knowledge of language and literacy development, mathematics, and special knowledge about safety, health, and hygiene. This link takes you to a fairly lengthy test preparation video for the Praxis exam for early childhood workers. Note that the test measures declarative knowledge using standardized methods which no doubt an AI test taker could pass. I wonder how AI entities would do in ECE work.

A weeks ago, protestors in Sacramento gathered in the capital area to communicate their frustration with rising demands for academic training to become an assistant teacher with no significant increase in pay. YouTube interviews with ECE workers tell us that ECE workers have stayed on the job because they cared for young children themselves when they were teenagers and they are committed to supporting children despite the living from hand to mouth. It’s hard to see a future working in ECE given the pay, they say.

Political leaders responding to questions about low pay from local Sacramento journalists repeated that money is on the way. They pointed to funding in the state budget spread over five years to support the new requirements. It appears that splicing ECE onto the K12 structure will trigger Proposition 98 funding protection, California’s legally required annual proportional allocation of the state budget to schools. In any event, money is coming, so sayeth the powers that be.

*****

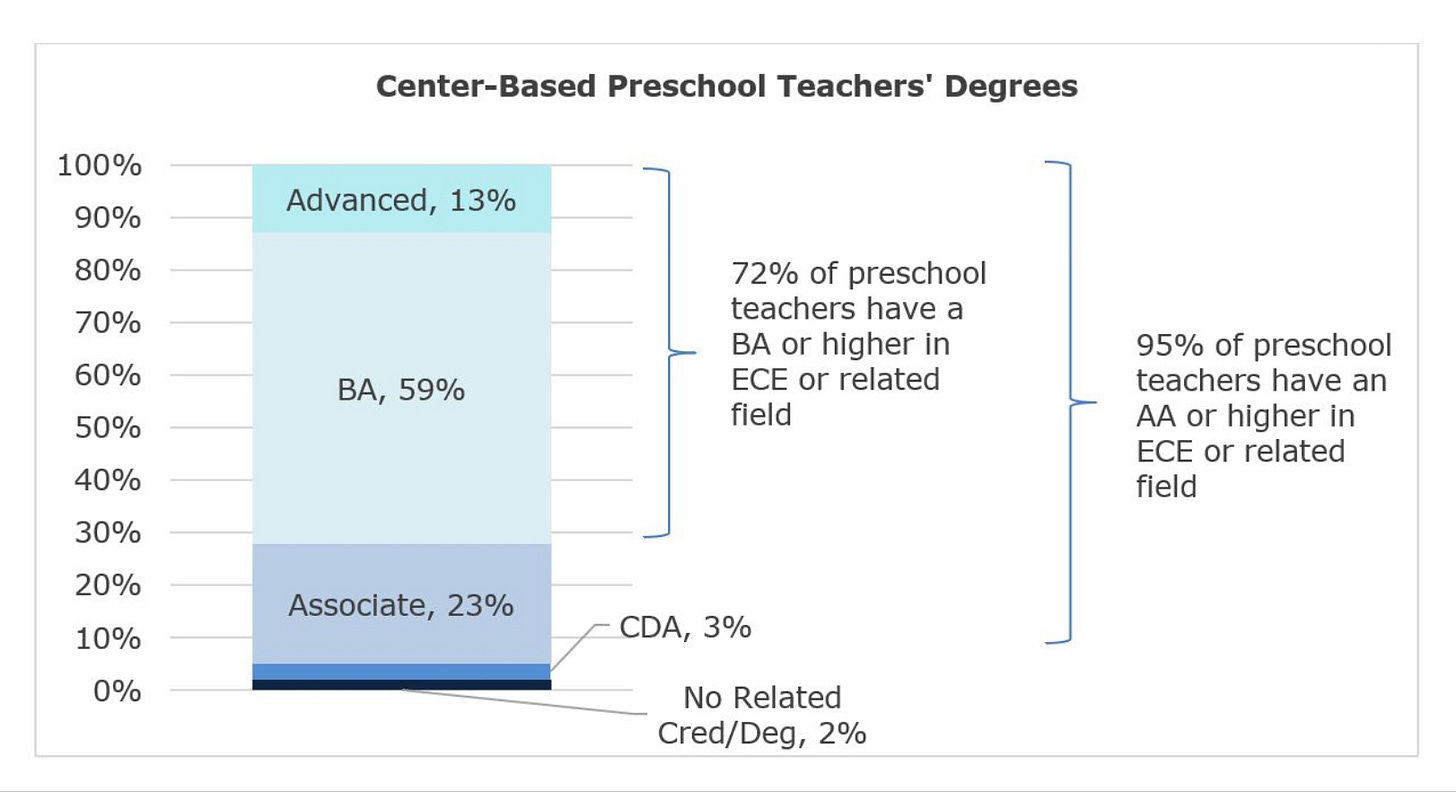

Recognizing the abundance of evidence published in scholarly work on the profound significance of the learning that takes place in early childhood, California leaders examined the component parts of the professional workforce that will be needed to bring the development to fruition:

The metaphor of a tree suggests an organic process for the growth of a sturdy ECE tree to provide shade for children in a world rapidly overheating. I’m puzzled by the geometry of the tree, particularly its unusual curves and isolated bursts of leaves, but a close reading of the verbiage undermines the naturalistic foliage. Each tier is headed with the phrase “shared core of knowledge and competencies,” suggesting a deep penetration of collective explicit and tacit knowledge across all of the tiers. But the subheading undercuts the heading: “differentiated/specialized knowledge and competencies” emphasizes workers in silos. The factory model consists of nested silos—classrooms, grade levels, school levels, and districts. Workers in this system can spend decades in isolated classrooms without ever knowing firsthand about activities in classrooms just down the hall.

How do the State planners propose to achieve “shared knowledge and competencies” by focusing in on “differentiated/specialized knowledge”? Professional silos in schools isn’t a way to spread deep understanding of mission, vision, and practice. The perspective reflected in the tree metaphor is comforting, but critical analysis of the substance highlights the need for vigilance in implementation.

On that note, a brief look at a recent empirical study (Geißler et al., 2022) published in a peer-reviewed journal6 offers a suggestion about how to ensure that the “quality of interactions” between the individual child and the caregivers remains high. As I mentioned earlier, if you take away all of the facilities, the parking lots, the kitchens, the custodians, the principals, the classrooms, the teachers’ manuals, all of the ancillary stuff of schooling—if you look for the heart of the work, here it is: the quality of the interactions between teachers and learners. Geißler et al.’s study described the development and validation of an observational tool used by trained raters to measure this quality. The findings are worth considering.

Where among the curves in the tree and the blobs of green leaves can we find the quality of interactions and the professional development and work to assure and improve it?

*****

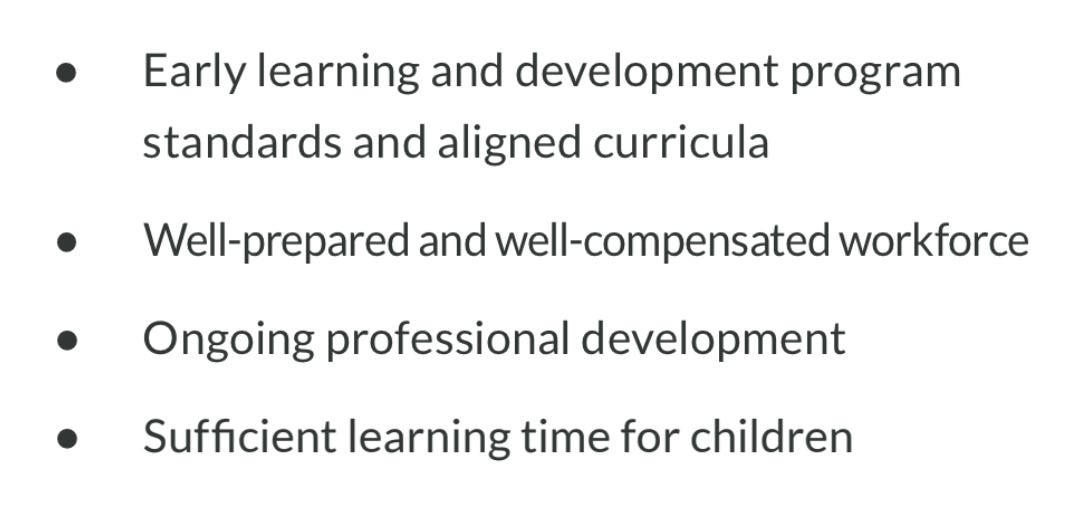

California’s Master Plan for Early Learning and Care gained traction in 2021 when the state budget allocated real money to establish universal preschool. The plan in practice centered around traditional concepts of the curriculum to transplant factory model structures of the K12 system into ECE. The following are goals in varying stages of progress:

I begin to worry, perhaps unjustly, about a disease infecting the ECE tree metaphor when I see the phrase “aligned curricula.” Indeed, alignment among program standards and instructional materials and activities stands between preparing and authorizing teachers to “do” expert work to provide high quality, responsive, and sensitive individual interactions. Traditional factory model thinking grinds on as managers strive to align all of the moving parts in standardized ways with widgets for learners.

Geißler et al.’s study (2022) on quality of interactions found that frequent team meetings among ECE workers produced measurable increases in quality of interactions. The idea of aligning instruction and materials with program standards may not change the outcome much if the real job is to position teachers to be able to align themselves in word and action with the circumstances of the individual in the moment of contact. What gets aligned with what—and how—in itself is badly in need of reconceptualizing. But curriculum standards, instructional activities and materials, and tests as a triangle is deep in our collective conception of school, as deep as the insistence that specialized knowledge and competence in silos will produce the schools we need to produce equity.

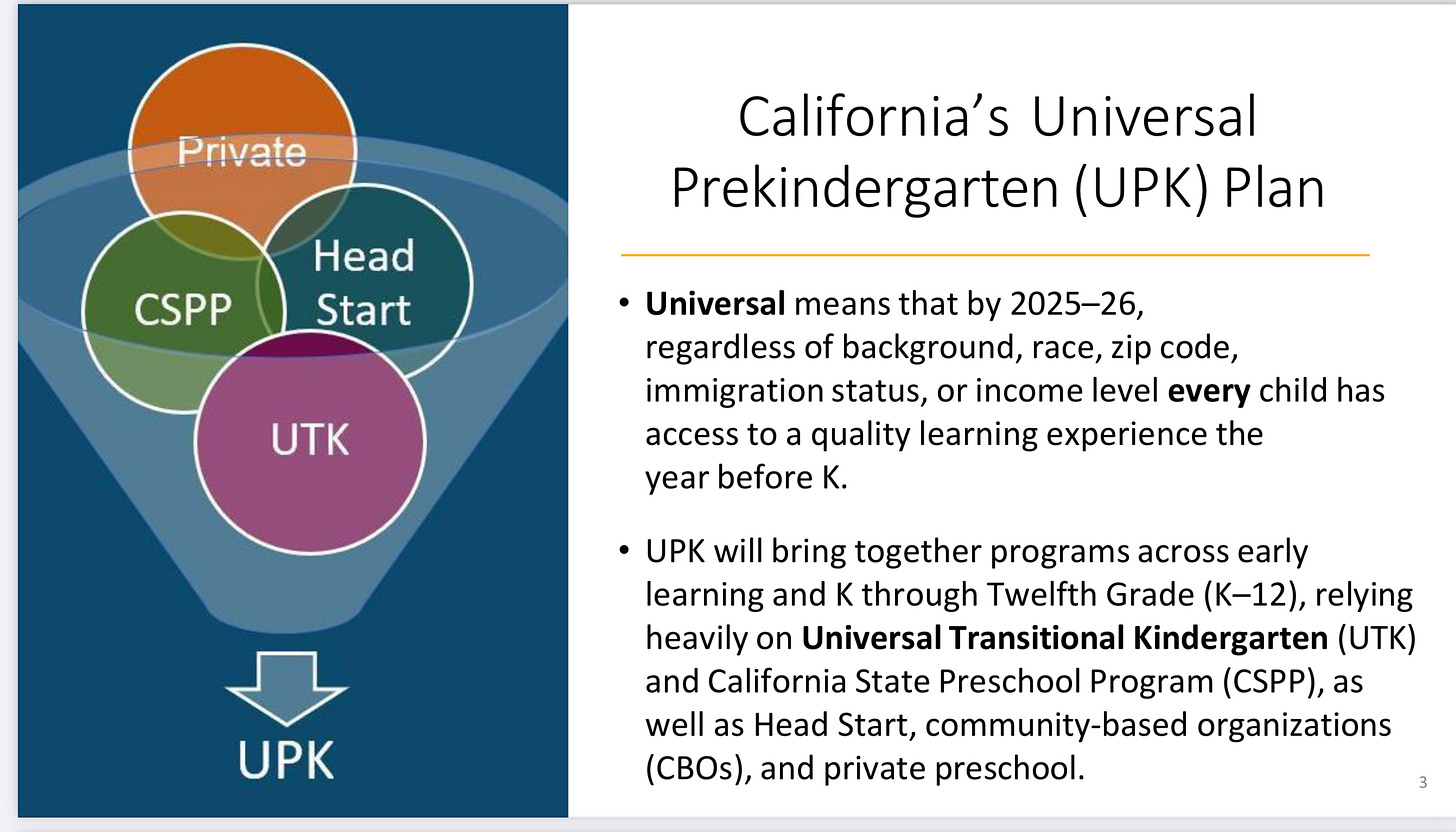

The California Department of Education was instructed to issue a request for proposals to begin spending money designing and implementing “a mixed delivery system” with a five-year vision, that is, a system that allows the public school system to contract with private instructional providers. Universal transitional kindergarten (UTK) represents a curricular hinge connecting the ECE to the established K12 system. As such, the question of who holds authority over UTK was an issue:

“The debate over a mixed delivery system, in which state-funded early learning programs could be held in a variety of community-based settings and not solely through public schools, revolves around issues of quality, equity and funding. Legislators and some early education advocates believe in a centralized approach, viewing transitional kindergarten, or UTK, as a new public school grade that shouldn’t be outsourced.”7

It appears that the year before the kindergarten year will represent a hybrid structure, part public, part private. From the Master Plan:

This spring, the State Department of Education began implementing an action plan involving repurposing structures already in place—not starting from scratch:8

The California State Preschool Program headquartered in the Department of Education has existed since at least the 1960s when federal Head Start funds began to flow. As the administrative mechanism for organizing this resource, CSPP currently “contracts with over 700 private, non-profit, as well as other public agencies so that low-income families can find safe, healthy, and age-appropriate educational environments for the care of their children. The care can be provided in licensed centers, family child care homes, as well as in homes and centers exempt from licensure.” The decision to outsource Universal Transition to Kindergarten vis a vis the mixed method model brings for-profit preschools into public education.

Resource alignment is important for achieving the vision, but where are the children? At the top of the funnel are three social and economic structures functioning in heretofore separate silos. When they meet to discuss financial issues, where will the children be? What comes out of the funnel is an institutional structure labeled UPK. Shouldn’t that be “high quality interactions” between teachers and learners? Sarason’s (1992) warning about the central cause of reform failure flashes red: Reforming based on the illusion that schools are child-centered will mean no reform at all.

*****

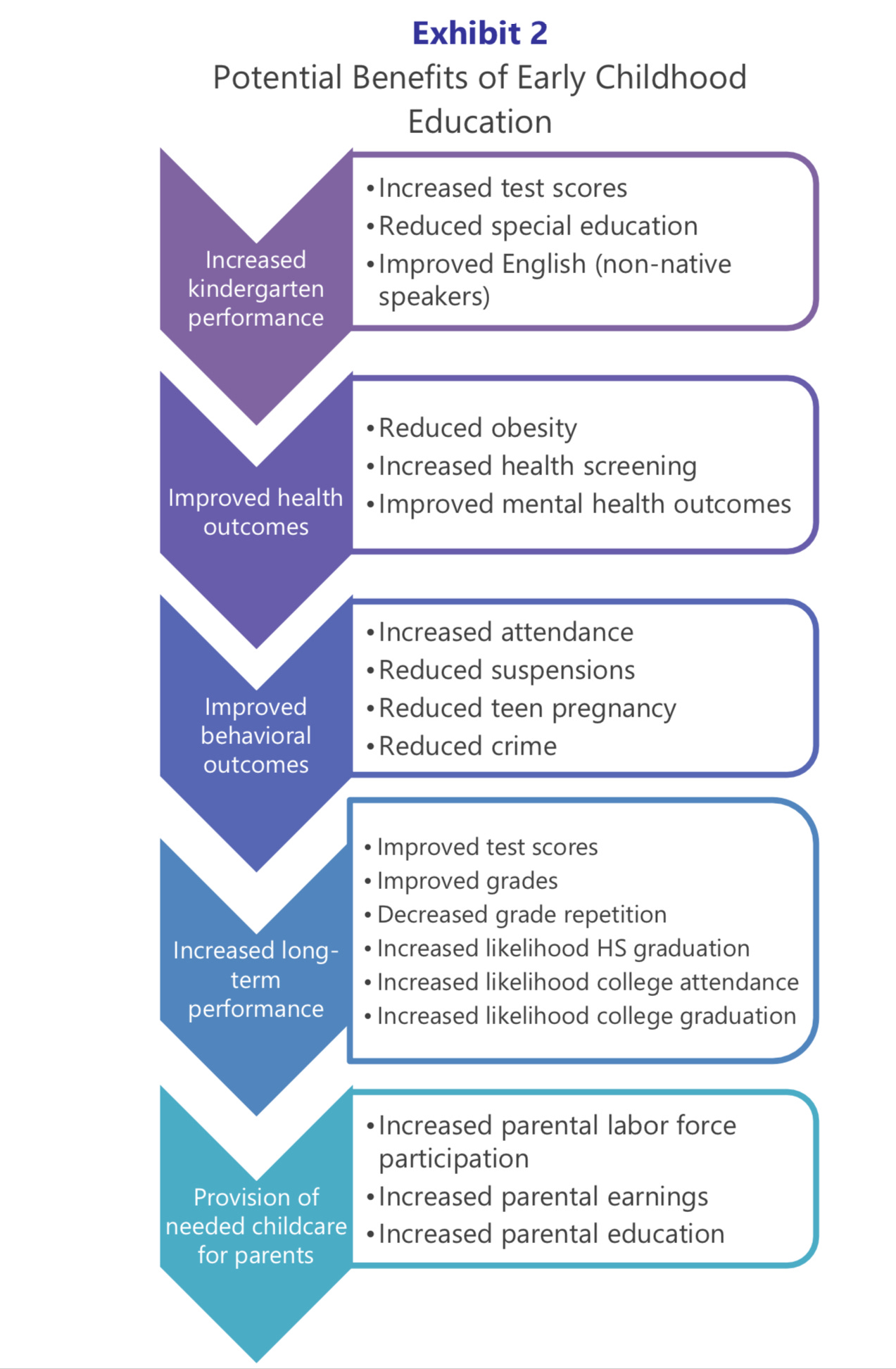

Investment in early childhood education could yield future benefits for all of society, benefits which have been mapped out in impressive documents. The following exhibit is excerpted from a 2019 document published by The Washington State Institute for Public Policy and cited in the California Master Plan in support of its argument to taxpayers that this expenditure will be worth it.

From outside looking in, all of these improvements in this diagram are compelling. No doubt the average person with the common sense notion that standardized tests are the linchpin that holds the system together, the figure is convincing. From inside looking out, the improvements look semantically hollow, because the graphic is saturated in the test and measurement culture that has created entrenched problems throughout the K12 system.

Notice that the outcomes are numbers without grounding generated by tests or by dichotomous summary judgments, and the evidence provided is expressed in quantitative data packages in the empty jargon inherited by the traditional K-12 system, both categorical and interval. Witness9:

Of course, if kindergartners don’t need as much special education, if rates of obesity fall, if teens attend school more regularly and get pregnant less, if fewer students are held back in a grade, if test scores improve and high school graduates increase in quantity as a result of preschool—is this graphic an argument for ECE on the basis of positive developmental cognitive and emotional consequences for children or on the basis of comfortable consequences adults find attractive? If I were three years old and you were trying to sell me on attending a certain preschool (picture your high school graduate making visits to college campuses to decide where to apply), are these the draw? Clearly, the assumption is that high schools will never change—they have been the most resistant to change. Can a reform movement with a stated goal of serving the needs of adults rather children deeply impact the social, emotional, cognitive, and linguistic development of the child?

I’m not sure what to make of “tests” in kindergarten in this exhibit, likely because I have little explicit, codified knowledge of quantitative measurement tools at this level at this point in time. The whole question of standardized testing in ECE has become controversial. The traditional conceptual link between tests and curriculum alignment concerns me. Though it’s not surprising that preschool experience would increase competence in kindergarten, it is surprising to me that increased test scores are reported for kindergartners, especially since any increase would be predicated on earlier test scores in preschool. Is California transplanting the college admissions process to kindergarten?

I’m wondering what this graphic might look like with a firm grounding in sociocultural theory. “Long term performance” is operationally defined in traditional high school terms: test scores, grades, retention, graduation, college enrollment, college completion—a collection of data points reified in the factory metaphor suggesting the troubling conclusion that curriculum alignment in ECE may grow the same culture of external academic surveillance and accountability in the name of pedagogical fidelity that now stands between teachers and professional self-regulated practices.

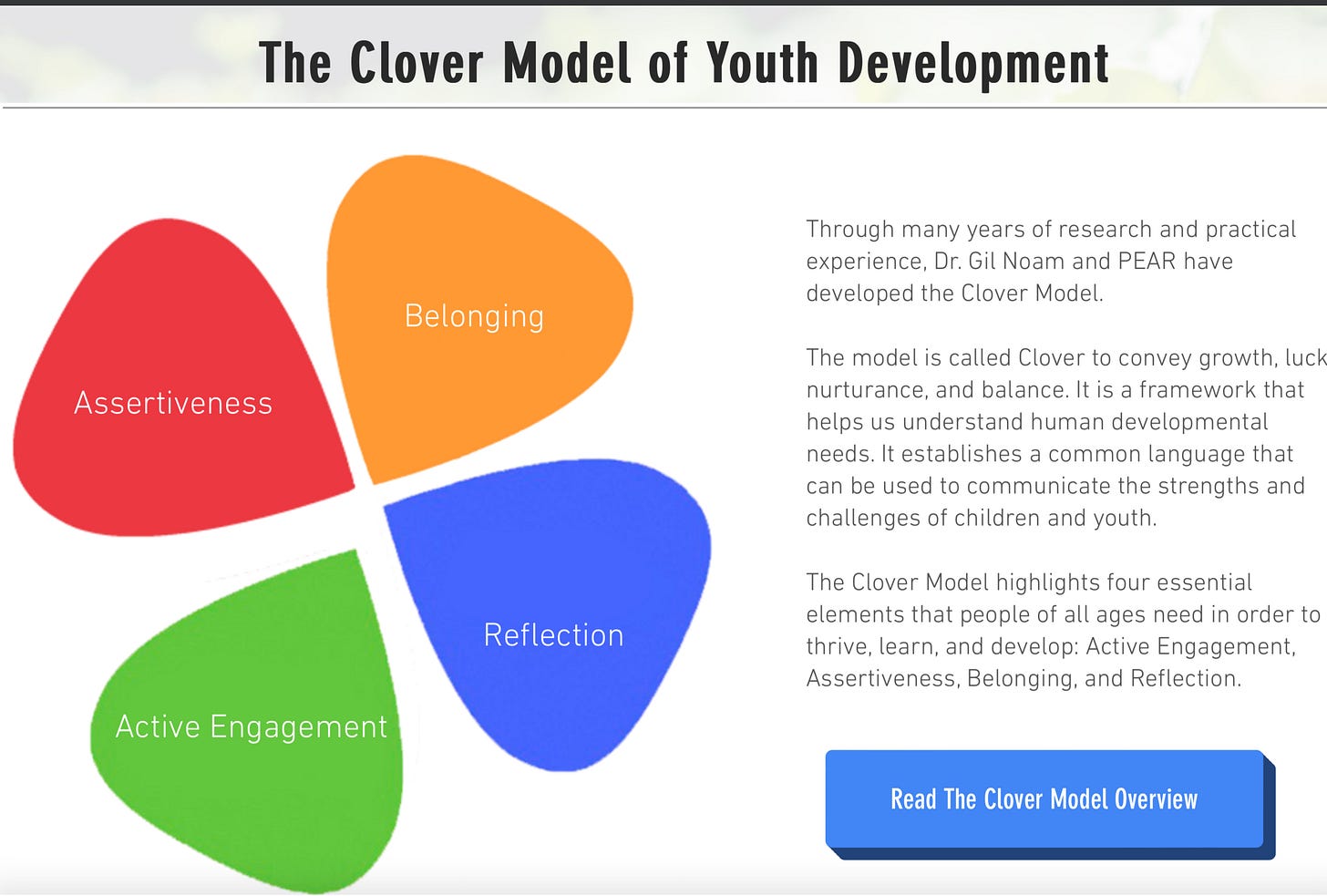

What if “long term performance” is defined as an ethical disposition, a staircase of experiences in mathematics and science, self-selected artifacts with audio and video reflections? What if “long term performance” is assessed along dimensions of learning like those depicted in the Clover Model?

*****

California’s Commission on Teacher Credentialing has been working on a set of teacher performance expectations (TPEs) for credentialing early childhood education (ECE) personnel since 201510. In the final stretch of adoption, the system for licensing ECE personnel consists of four levels: assistant teacher, teacher, master teacher, and administrator.

Essentially, the core of the work for each credential level is defined by increases in responsibility for accomplishing the larger mission of a preschool together with decreases in the amount of time spent working with children.

In effect, the higher and more developed the quality of expertise of the educator, the less time that individual spends with children. Recalling the 2022 study that put “quality of interaction” between teacher and child at the heart of the work, one wonders about the wisdom of this plan for deployment of expertise.

[Please note: My observation is not intended to denigrate the work of the CTC on this project. The substance of the TPE document is light years ahead of the chaos from which it emerged, as near as I understand it. Having worked with CTC on writing proposals for a Reading Specialist credential program, on field testing of basic teaching credential candidate assessments, and on writing proposals for restructured teacher preparation programs, I know firsthand the competence, commitment, and professionalism of this Commission. CTC works in the real world and does remarkable things often in the face of powerful people looking at public schools from a great distance.]

Assistant teachers spend much of their time with children, carefully distinguished in the CTC document from “students.” Through the extensive list of TPEs, those who are appropriately prepared for the assistant role understand that they work for the teacher. Less obvious in the TPEs for teachers but nonetheless implicit, those who teach understand their obligation is to work for the family and the administrator. The master teacher is obligated to work for the administrator and the teacher. The administrator works for the State. No one, it appears, works for the learner:

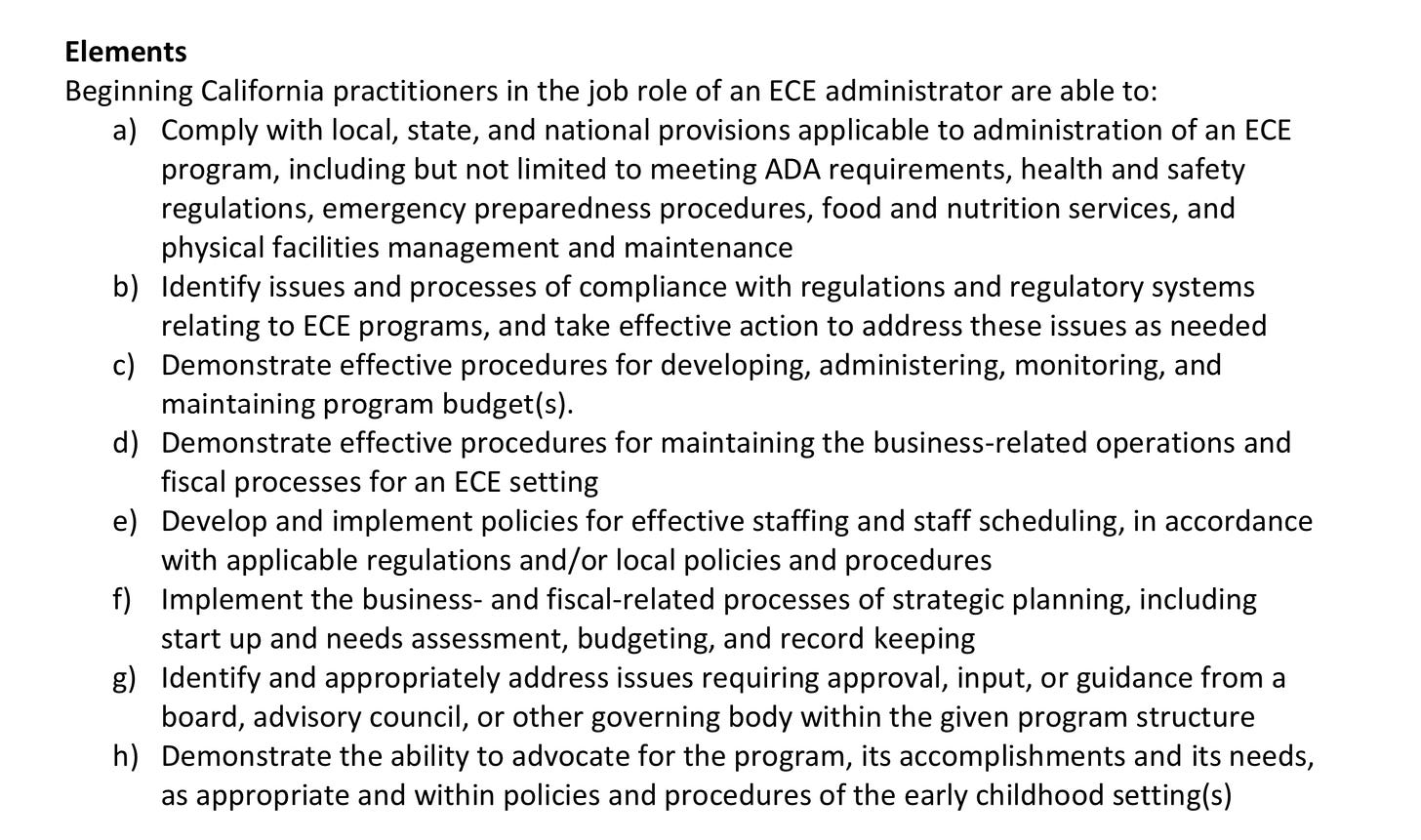

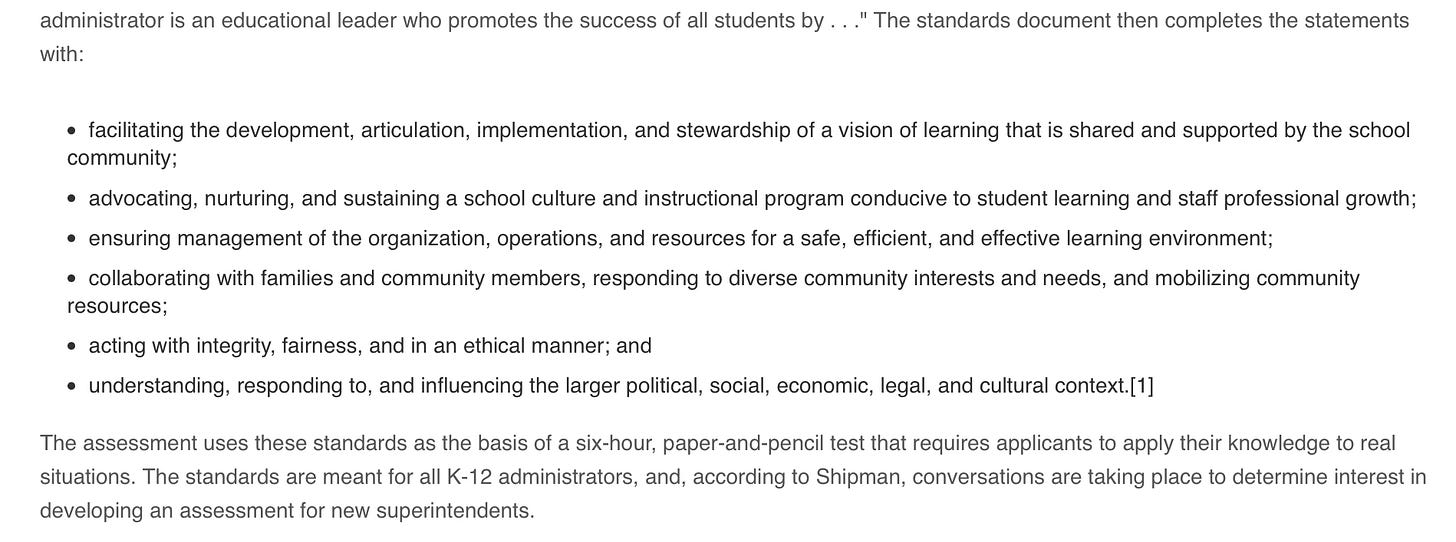

Around 1996, a consortium of states was formed to explore what a set of standards for educational administrators in a reformed public system might look like. Standards for student learning had been in play for a while, reaching a crescendo along with standards for the teaching profession. Somehow, standards for educational leaders slipped between the cracks until the end of the century. Contemporaneous reports say that crowds at management conferences overflowed to learn about “quality,” a buzzword among business leaders11. Notice that the following excerpt (Lewis, Oct 1997, Phi Delta Kaplan) of the old “new” standards makes the new standards for principals in California look very old:

Health and safety concerns, emergency preparedness procedures, food and nutrition services, physical facilities maintenance and management—these are crucial aspects of any preschool management, and perhaps they must land in the lap of a principal. Being an advocate for the program and interacting with governing bodies are also important aspects of operating a preschool. I begin to grimace a bit as I read through the set of TPEs governing the job of the administrator in the area of professional development:

These expectations are troubling from the perspective of advocates for a deep change from bureaucratic to professional accountability (Darling-Hammond, 1989). Engaging in reflective practice is one thing; administrators like all other educators can improve through structured reflective analysis of their work. But positioning the administrator as on-site surveillance of “the quality of instruction and interactions” has real impact on the quality of teacher self- and peer-assessment, recognizing that within-person and between-person self and peer observations create a synergy that builds expertise.

Similarly troubling is the expectation that administrators require staff to prepare “personalized professional growth plans” in a context of surveillance and asymmetrical power relationships. To make clear that administrators work as proxies for the State rather than advocates for the learners and their teachers, these “personalized” plans must be based on “state-adopted requirements and other identified needs.” What about self-identified interests and questions among the teachers?

Because the administrator is expected to “identify and address areas in need of improvement,” it appears as if the administrator is expected to supplant the kind of self- and peer-assessment practices that can promote local inquiry and collaboration in clinical research in areas of need identified by master teachers, teachers, and assistant teachers practicing in professional communities. Within such communities an administrator to “help staff access professional development resources” and “provide professional development activities” repositions the principal as a critical friend rather than a State-sponsored surveillance agent. California missed a real opportunity to lead the nation.

*****

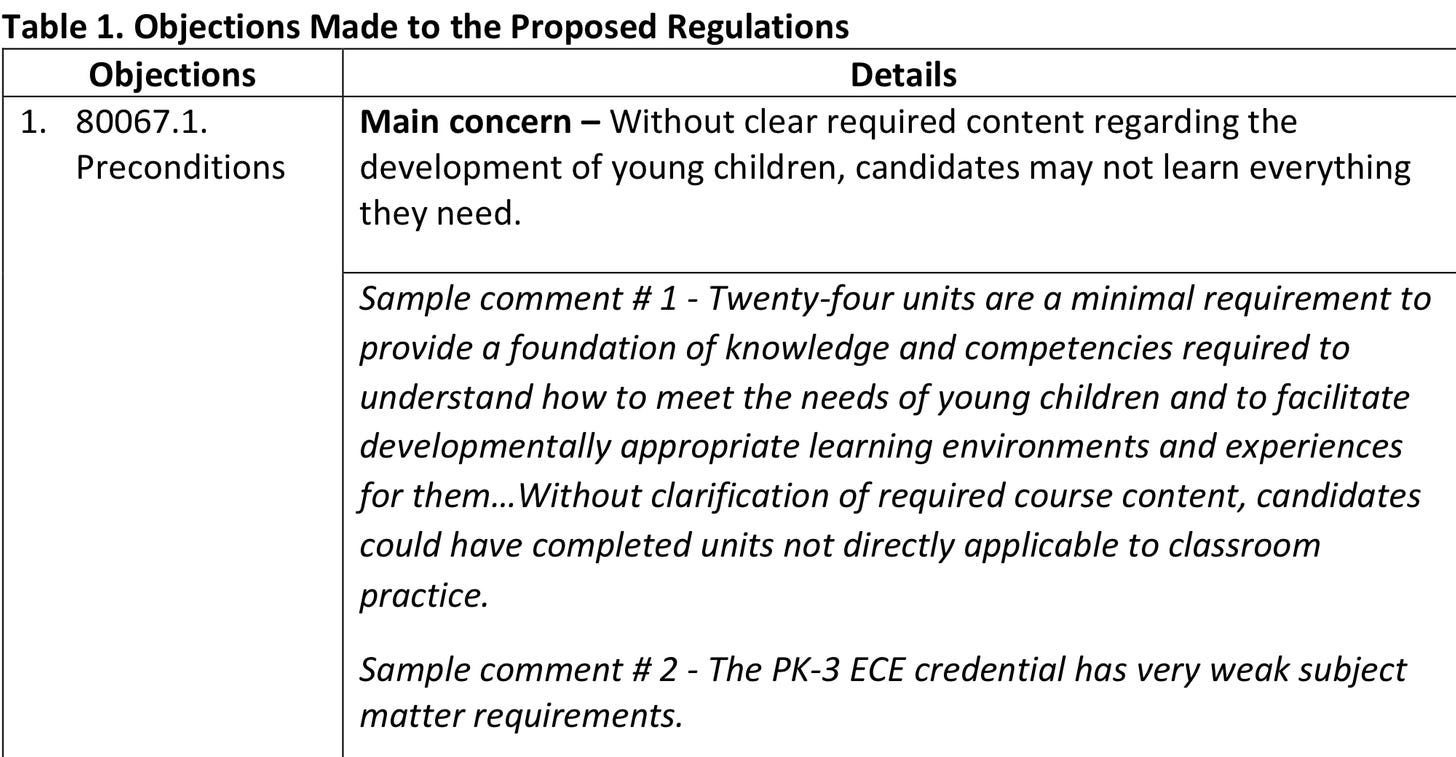

CTC completed a rigorous round of opportunities for public review of and comments on the new standards as they emerged over many months. During the final stage of work, CTC got predictable complaints from the public about keeping comment opportunities in the shade, not being well publicized, and related bureaucratic obstacles put in the path to prevent public input. One theme in the final stretch of the work intrigued me in regard to the assumption of the CTC as the arbiter of course content in a university program:

I don’t have the expertise nor the experience to comment on the table of contents of a foundations in ECE textbook, but the timing of this objection reflects the nature of school culture under a bureaucratic accountability formula. In my experience, as documents like this with regulatory force unfold, most teachers track them from a distance, believing that they as individuals have no meaningful way to impact the discussion, sometimes buying into hyperbolic rumors of impending disasters—perhaps with good reason. I, personally, expect that the CTC ran a good process based on my experience. In this case, the time to request specification of course content is before the curriculum standards are written, not at the stage of tweaking. But the issue itself is of profound importance. How teachers are prepared is second in importance only to how they are allowed to practice when it comes to the quality of day to day interactions between the teacher and the learner.

The comment about “24 units” being insufficient curricular space for candidate preparation highlights the degree to which universities themselves are complicit in the measurement mentality. As a university professor with experience in institutional assessment, I’ve got a raft of problems related to the unintended consequences for learning flowing from the Carnegie unit in higher education. As others have remarked, the idea that the number of hours a person spends taking a course translates to learning is completely flawed. The effort to put human learning into a matrix requires courses, units, tests. The system runs the people.

*****

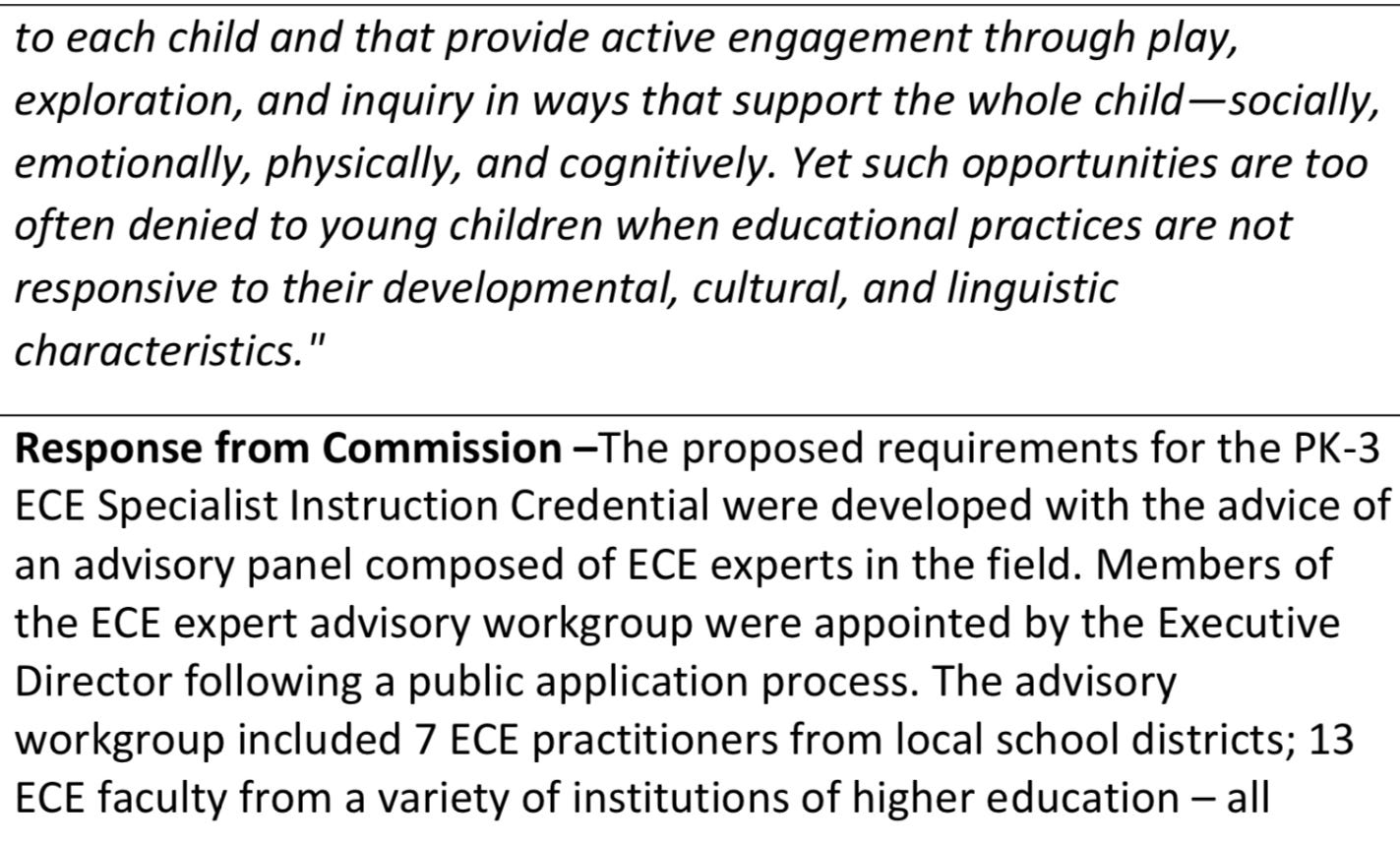

Philosophical or scientific objections to root assumptions, theories, and concepts from the publi appeared near the end of the final public comment phase. Here, the complaint went to the implied child in the standards taken as a collection. In the eyes of the beholder, the standards appeared to fracture the child into pieces where a proper view would address the “whole child” and the complainant suggested that these standards “are not responsive to…developmental, cultural, and linguistic characteristics.”

CTC responded in the only way it could respond to an argument that crushed the center of a nearly finished document. Now we wait and watch and hope. The potential to improve long-term outcomes for children in California is far stronger than it was before the Master Plan. Coherence, continuity, and intentionality even with deeply troubling issues could make a difference. If it were me, I’d take a hard look at revising the administrator standards as a starting point. Strong instructional leaders in administrative positions who can foster a vibrant, shared vision are gold; giving them a license to lead could be the difference between real progress and marginal change.

https://cdn-west-prod-chhs-01.dsh.ca.gov/chhs/uploads/2020/12/01104743/Master-Plan-for-Early-Learning-and-Care-Making-California-For-All-Kids-FINAL.pdf

https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/

https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/Estimating%20the%20Cost%20of%20Preschool%20for%20All%20in%20California_0.pdf

https://eclkc.ohs.acf.hhs.gov/about-us/article/head-start-program-facts-fiscal-year-2021

https://airtable.com/embed/shrpMjZ2gSN4UK8t7/tblCdTtTjOrf5A8hQ

https://journal.fi/jecer/article/view/114008

https://edsource.org/2021/why-some-early-childhood-advocates-want-more-transitional-kindergarten-choices/656600?amp=1

https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/educator-prep/files/pk-3-technical-assistance-nov2022.pdf?sfvrsn=508d26b1_3

https://www.wsipp.wa.gov/ReportFile/1710/Wsipp_Early-Childhood-Education-for-Low-Income-Students-A-Review-of-the-Evidence-and-Benefit-Cost-Analysis-UPDATE_Report.pdf

https://www.ctc.ca.gov/docs/default-source/commission/agendas/2023-04/2023-04-3i.pdf?sfvrsn=8c9021b1_6#page10

https://web-p-ebscohost-com.proxy.lib.csus.edu/ehost/detail/detail?vid=2&sid=1d86396a-7457-4d7d-966f-ddc83b009016%40redis&bdata=#AN=9710150584&db=a9h

I would agree starting with leadership expectations/standards makes sense. How do we ensure engagement and commitment? We don't want a surveillance system, yet I know things don't get done consistently across schools/districts unless there is some type of accountability system.