Is formal education even possible any longer? Has the traditional purpose of formal schools, i.e., to produce knowledgeable and thoughtful human beings, fallen by the wayside? Have we forsaken the humanities?

In a recent YouTube, Professor David Steiner, an experienced and thoughtful voice in matters of education policy, argues that beginning around 1990, large-scale data collected nationally suggest that reading abilities began to fall, and they have fallen consistently since 20001. Steiner casts progressive education in the role of villain in the script he believes has played out under the banner of reading instruction in elementary schools. Phonics, though it must be taught, teaches children to read nonsense books, he complains. Reading comprehension is taught through empty skills like getting the main idea, he quibbles. Characterizing reading instruction as progressive because it lacks knowledge at its center, he sees that some version of child-centered philosophy has infected the entire system. Knowledge-centered instruction flowing from a knowledge-based curriculum derived from Western Classical education is the ticket,

Steiner’s premises for a model of effective formal education organized around knowledge are surprisingly simple for such a complex theoretician. I’m stating my interpretation of his premises below based on a fulsome listening to his message. To double check for distortions I may have inadvertently introduced, you will need to see for yourself by watching. I found it truly interesting. Although I disagree with his analysis and his premises, I was fascinated with his interpretation of Immanuel Kant’s views on the relation between beauty and truth, reason and imagination, and implications for academic discourse genres—fast forward to around 37 minutes, a highlight of the keynote. Steiner locates the most powerful reading performances available for classroom assignments at the intersection of comprehension and imagination, a brand of aesthetic reading that includes texts from literature, about history, and within science.

The questions that follow the keynote are also powerful, especially one from a Ukrainian woman taking issue with Western Great Book programs and another from a new PhD from the Philippines lucidly skewering the traditional Great Books argument with her experiences as a child having to read colonialist books.

Steiner’s responses to these challenges are unconvincing, in my view. They are tautological, reminiscent of his attacking and then using reading test scores. Our country is in danger of forfeiting classical education thanks to liberal progressives, according to Steiner. His presence and obvious depth of knowledge carry weight in venues of power. This debate is taking place at the highest levels of society pointing toward the renovation of classical education through legislation, returning the White Western canon to our system, an extension of the voluntary State selection of David Coleman’s Common Core and a philosophy of close reading of texts worth reading

Texas, for example, is facing curriculum turmoil right now grounded in part in a disagreement what counts as knowledge vis a vis religious ideologies. The discussion has nothing to do with education and everything to do with power, particularly political power. The goal in Texas is to establish a statewide knowledge curriculum to guarantee every Texas child access to a coherent, standardized knowledge base shared by every student who completes high school. Accordingly, every children will read the same books the same way under the same conditions and answer the same questions and carry away carbon copy knowledge required to comprehend more complex carbon copy knowledge in high school. Me: AI is a Texas nightmare, a wildcard, a tiger. According to Steiner…

Premise 1: Formal education is possible only when adults exert strict control and authority over the minds and bodies of children and over what they read. Teachers are knowledge experts, and their proper function is to transfer knowledge. It is the State’s obligation to assert what knowledge counts most. What knowledge counts most is derived from the humanities (the classics) with science and mathematics in the mix.

Premise 2: Children are incapable of knowing and understanding what is good for them or what they need. They do not have classical knowledge and will lead impoverished and unsatisfying lives without it, disadvantaged as participants in society as thinkers and knowers. Particularly troubling, their reading comprehension scores will remain low.

His warning: We are experiencing a “retreat from knowledge” fueled by a radical liberal political force. Child-centric education is the root of the problem. Knowledge-centered education is the solution.

Here is information about his background from a webpage:

“He currently serves on the board of the Relay Graduate School of Education. Most recently, he was appointed to the Practitioner Council at the Hoover Institution at Stanford University. He previously served on the board of the Core Knowledge Foundation, Urban Teachers, as commissioner of education for New York State, as the Klara and Larry Silverstein Dean at the Hunter College School of Education, and as director of education at the National Endowment for the Arts.”

*****

Clearly, when David Steiner speaks, people listen. His autobiographical history as a scholar, beginning with his undergraduate preparation at Oxford in philosophy, politics, and economics and terminating with masters and doctoral degrees from Harvard in political science, imply a deeply rooted interest in education policy. Born in America on the east coast in 1958 into an academic family, he was raised in Cambridge, England, where he attended Perse High School, founded in 1615.

When Steiner attended, Perse enrolled an all-male student body (females were admitted in 1994). The following screenshot gives you some sense of the type of “knowledge” Steiner formally learned as a male in an all-male high school, reminiscent of the classical background of fellow Oxford graduate David Coleman, principal architect of the Common Core. I find it curious that highly influential political agents would design and legitimate a model of schooling created by Oxford graduates for children and adolescents going to school in rural areas, urban centers, and prairie towns.

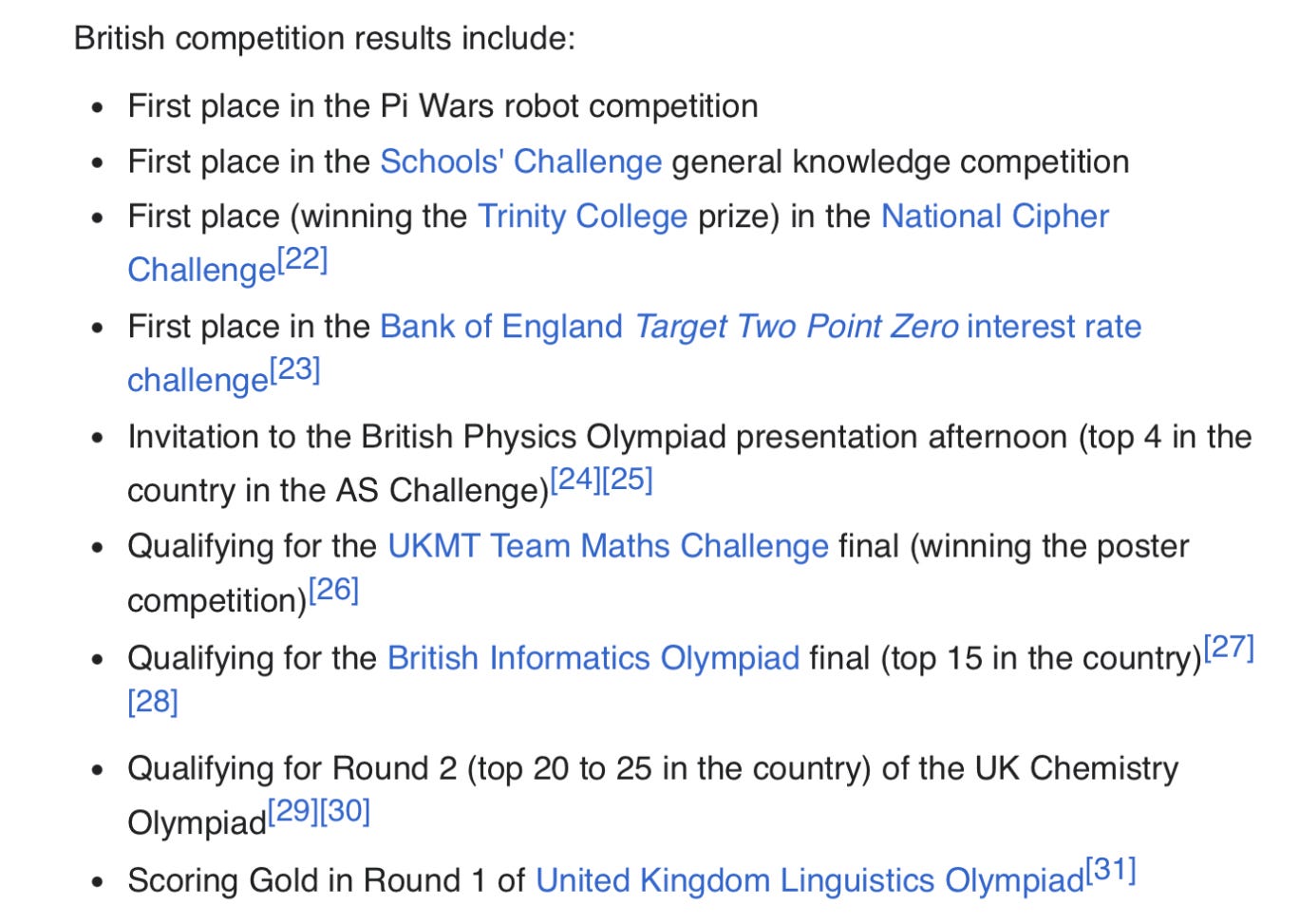

Perse is known for a strong track record of winning academic competitions. It makes some sense that a high school student who cut his academic teeth in a highly competitive culture based on recall of information would be antagonistic toward a real or perceived “retreat from knowledge”:

*****

Policy-making about formal schooling in the 21st century is built on the theory that children can be converted to abstractions—t scores on a bell curve, cognitively similar in age-alike cohorts. Policy regulates what is supposed to happen in classrooms to these abstractions along a series of one-year bands.

When an abstraction materializes in a classroom in flesh and blood, formal learning begins, according to Steiner with primary stress on ‘formal.’ Blank slates they are filing in to take a seat, he avers, for all practical purposes, and they must learn quickly to sit quietly in chairs and follow directions (recall Dewey’s thoughts on movement in activity, movement in activity fueled by interest and intentions), and that is how it should be—if high schools are to produce wins in academic decathlons. Without authoritative guidance, children will be like bats searching for caves, David Steiner asserted to underscore the moral obligation of the policy-maker to protect children from ignorance.

Well-known figures in the struggle for civil rights are included in Steiner’s reference list in his keynote YouTube, figures whose use of knowledge in resistance to oppression for Steiner proves the worth of the Western canon in the quest for a humanized world. Frederick Douglas, Martin Luther King, and Malcolm X, according to Steiner, “each affirmed the centrality of classical learning in their resistance.” He also included Nelson Mandela in his list of exemplars.

He singles out the historical biography of Malcolm X, who dropped out of high school at 13 and wound up in prison for robbery where he read Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, and Nietzsche, etc. This reading of classic literature humanized Malcolm X and motivated him to take a stand as we learn in the Autobiography of Malcolm X. He discusses Mandela’s imprisonment at Robben Island for 27 years where Nelson Mandela organized the inmates to produce plays as a way to engage in the world. Mandela himself selected and volunteered to play the roles of both Agamemnon and Antigone in Sophocle’s play as a vehicle to grasp the emotions of Agememnon, the powerful oppressor, and Antigone, the resistant one, the seeker of justice.

Ironically, though Frederick Douglass was a voracious reader and would have loved to have been allowed to go to school, he was a slave and had no legal access. Malcolm X started reading in the jailhouse, not in the schoolhouse, and he received no direct instruction, no delivery of topical knowledge. Mandela was well-educated as an adult, but his early education deserves a bit of elaboration. I quibble with Steiner’s selection of this trio of civil rights heroes as poster children for a Western classical education.

Mandela began his primary education at a local Methodist school near his village in Qunu, where he was given the English name "Nelson" by his teacher. English was the primary language of instruction, despite not being the native language of most students; English was seen as a means of civilizing and preparing them for possible employment in colonial administration or missionary work or for manual labor and domestic service roles within the colonial economy.. They were taught to read, write, and speak English through grammar lessons, dictation, and reading exercises. The curriculum aimed to assimilate African students into European culture and values through teachings about British history, geography, and literature, with little or no reference to African history and culture.

Clearly, knowledge of the humanities deepened these influential figures’ commitment to resist oppression, but Steiner never addresses the fact that Frederick Douglass learned to read on the streets of Baltimore under the tutelage of white children who helped him keep the lessons secret. Malcolm X read the classics because he was locked away and needed a connection to life. Nelson Mandela was subject to indoctrination at the hands of colonizers who wanted to dominate him. How these figures reveal the strength of a national knowledge curriculum mandated by the federal government as Steiner seems to want remains a mystery to me.2

*****

The starting point of the policy debate is an abstraction. In its current iteration relevant to literacy pedagogy the debate is illustrated by the Twin Science phenomenon. In one science, teaching learning to read and write is prescriptive and uniform, a technical process, and requires authoritative, direct instruction, better accomplished with a teacher-proof script, an approach which inherently places the teacher in the role of controller. Blank slates sit passively in a vacuum and follow directions, mouthing sounds, focusing on letters and sounds rather than sense and meaning. Little by little teachers add markings to these blank slates until soon a child can read nonsense in a phonetically controlled text.

In another science, learning to read and write is a sociocultural process involving a technical process, a natural extension of early childhood language experiences, and teachers are responsible and responsive agents working to gradually release responsibility for accomplishing the goal of an activity to the learners. Both sides of the debate agree on the goal of learning: Children need to learn to read. They need to build knowledge to make knowledge. They don’t agree, however, on what it means to read and on the level of control over the thought processes of learners teachers need.

Steiner’s view, though more articulate and erudite than most voices in agreement with his conservative ideology, still ignores the paradox at the heart of teaching and transforms the problem into a binary. The goal of formal schooling, on his view, is knowledge acquisition, i.e., memorized expertise. One can be child-centric or teacher-centric in response to the task of knowledge acquisition. According to Steiner, child-centrism is almost a form of child abuse, professional malpractice. Children do not know what they need to know. Turning them loose to learn from experience, from activity, from peers is equivalent to giving them unlimited soda or ice cream. They have fun, they like it—but what happens at the Science Olympiad in high school?

*****

For the uninitiated, I’m going to run down a list of fellow travelers with Steiner. These are folks who at one time or another embraced a strong teacher-centric stance, the teacher as authority figure and thought controller. In each case, the critical missing piece was a firm, clear understanding of the zone of proximal development in human learning, an appreciation of the significance of legitimate peripheral participation, of insights from decades of study of academic achievement motivation, of the centrality of metacognition in epistemology, of the vital part voluntary interest and its corollary, an intention to learn, plays as a goal and an instrument of teaching.

Arthur Bestor, an American historian and educational reformer influential in the 1950s and 1960s, is known for his strong advocacy of a traditional, liberal arts education and his critiques of progressive education. Bestor believed that the core of the curriculum should be the liberal arts, which he defined as the study of language, literature, history, mathematics, science, and foreign languages. A vocal critic of progressive education, he argued that child-centered learning was anti-intellectual. His book titled Educational Wastelands: The Retreat from Learning in Our Public Schools echos the title of Steiner’s keynote: Education in retreat.

E.D. Hirsch, a foundational thinker in the Knowledge Matters! campaigned, advocated for a content-rich, teacher-led curriculum, arguing that schools and teachers as authoritative sources of knowledge have one function: to impart a shared body of knowledge to students. Teachers should follow a sequential curriculum explicitly teaching this core knowledge. He was critical of tropes like ‘learning how to learn’ that postponed actual learning. In common with others making this argument, Hirsch believed that feeding knowledge to all students in equal portions using approved recipes and ingredients, regardless of student background, was a matter of equity and social justice, a way to level the playing field. His scholarship informed David Coleman and the Common Core.

Hirsch cited the following language from the Common Core in the final chapter of a monograph titled Knowledge at the Core in a chapter explaining why Hirsch likes the Common Core:

“By reading texts in history/social studies, science, and other disciplines, students build a foundation of knowledge in these fields that will also give them the background to be better readers in all content areas. Students can only gain this foundation when the curriculum is intentionally and coherently structured to develop rich content knowledge within and across grades.”

But Hirsch was also disappointed in Common Core. Like Steiner, Arthur Bestor, and the Knowledge Matters! campaign, the standards did not go far enough. The standards did not touch the third rail of American schooling: Schools as governmentally sourced indoctrination. In Hirsch’s own words:

“The words quoted above don’t define the specific historical, scientific, and other knowledge that is required for mature literacy. (If they did, no state would have adopted the CCSS, because specific content remains a local—or teacher—prerogative in the U.S.) But those words are an impetus to a brave and insightful governor or state superintendent to get down to brass tacks. In early schooling, progress cannot be made without coherence and specificity. Little can come from today’s incorrect but widespread assumption that critical-thinking or reading-comprehension skills can be gained without a specific, systematic buildup of knowledge” (p.80).

As Secretary of Education under President Ronald Reagan from 1985 to 1988, William Bennett was a conservative voice in education policy for several decades. Bennett earned a Ph.D. in philosophy from the University of Texas at Austin in 1970 with a dissertation focused on the ethical philosophy of Immanuel Kant (Steiner discusses Kant’s Ethics and his Aesthetics in the YouTube). Although Kant defies easy ideological classification, his moral philosophy of duty and obedience and respect for authority align with traditional conservative values—and with Steiner’s premises of teacher as authoritarian and learner as clueless and uninterested.

In 1984 Bennett published a report on a committee investigation of instruction in the humanities in American universities. The report, titled To Reclaim a Legacy, inventoried the evidence that student presence in great books type seminars and classrooms in universities was sadly evaporating because of lack of educational leadership. His solution to the problem, though far less nuanced and complex than E.D. Hirsch, nonetheless towed the conservative educational party line. Notice in the following excerpt Bennett’s view of the humanities as a body of objective content with specific, definite answers to questions, received knowledge that ought to be imparted by great lecturers:

“Expanding on a phrase from Matthew Arnold, I would describe the humanities as the best that has been said, thought, written, and otherwise expressed about the human experience. The humanities tell us how men and women of our own and other civilizations have grappled with life's enduring, fundamental questions: What isjustice? What should be loved? What deserves to be defended? What is courage? What is noble? What is base? Why do civilizations flourish? Why do they decline?” (p.15)

Charles Murray co-authored The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life (1994), a book almost universally reviled for its claims about race and intelligence in university divisions of education. I shall not repeat its specious claims in this space, but it is relevant that Murray argued that progressive education reforms have eroded authority and hierarchy in schools leading to declines in discipline, respect for teachers, and academic standards.

In a cruel, distorted, and indefensible manner, Murray criticized any focus on equality in school, noting that differences in ability and motivation among students are fixed and natural. Innate cognitive ability accounts for academic accomplishment, on this view, and policy-makers are foolish to try to eliminate differences in intelligence. A proponent of school choice and vouchers, he believed the market place would sort out students in terms of their potential, and the most effective pedagogy for all is a teacher-centered authoritative presence in every classroom delivering a classical liberal arts curriculum important for developing character.

*****

Of course knowledge matters. But children matter, too. Teachers matter. My biases show in this post, and I’m sure many readers have strong feelings about this topic. My interest in surfacing the issue stems from the crescendo of voices in the Science of Reading, Phonics Subcommittee, teaming up with the Knowledge Matters Rump Committee seeking to enshrine traditional authoritarian principles of White Western epistemology that advantage the affluent and frustrate the working class. Ironically, the knowledge argument asserts that (phonics and knowledge = reading and writing) + (reading and writing = college and career ready) is the solution to the learning gap between the haves and have-nots, which has been renamed the knowledge gap.

Knowledge is power right? In the case of Knowledge Matters, power is knowledge. Foucault taught us to beware of powerful people prescribing what lesser mortals need to know.

In the keynote, however, Steiner diminishes the value of his evidence by his own admission that reading comprehension tests are essentially useless because they measure processes. Under his regime reading comprehension tests would serve as measures of knowledge. He says this indirectly by criticizing the curriculum-free design of standardized reading tests. They are designed to offer everyone the same advantage—reading fairly short texts which rarely are read in schools and then answering the same questions with the same menu of choices. It is a bad design, but one cannot criticize a measurement tool and then use it for evidence of a crisis. Usually, it’s the other way around. One compiles evidence of the reliability and validity of the tool and then decides whether to use it.

The information about Malcolm X and Frederick Douglass is old knowledge for me from long ago readings of Frederick’s first autobiography about his childhood (he wrote several others, two I think) and Malcolm’s autobiography. I read several online sources regarding Mandela’s play (it’s a fascinating literacy story I’ve started to write up for a later post). I believe I capture the facts of Douglass and Malcolm X accurately. If readers see anything that needs to be changed, please email me or comment. I can edit this post and notify readers of any changes.

This was a fascinating history of the educational debate between classicism and progressive ideology. My education leaned more heavily on the Western classical / liberal arts / Great Books approach; and I guess by nurture, I have a deep love for the humanities and have tended to appreciate that knowledge-centered approach. However, as a educator working with students who have special educational needs, I also know that this approach falls short. Many of my students do have to be taught how to learn in order to remove the barrier of entry to knowledge. I have had to differentiate with sources of knowledge, methods of teaching; a single piece of literature would not have reached all my students the same way.

And then there is the matter of colonialism and over Westernizing education to the neglect of other voices and contributors in the humanities. That was a significant goal of colonialism, imperialism, the residential school system -- to improve less-developed cultures and societies by spreading (typically) Euro-centric values and education. It is sad that in a world that supports democracy and idealistic freedom, we still imperialize and oppress (underhandedly and perhaps often unintentionally) by suggesting that only a certain slice of the planet has elevating truths to share.

This is an important reminder for me as an educator: the strength and beauty of so-called knowledge does not lie in itself, but rather in how it connects to people. That's why it's called the humanities, right? Because it captures the essence of the human experience and invites us to explore it and be in awe. The people -- both the students and those we choose to study -- matter too.

Thanks for sharing your son’s experience, Matt. Choice is powerful in teaching and learning. The example of knowledge from political science situated in a current issue sure to be of interest to many students is perfect. We can’t really use the word “child-centered” in this case, but we classify the approach as “learner-centered” in its attempt to allow for “opting in” even before the learner steps into the classroom. Interest, even a smidgeon, makes all the difference. Great comment! Thanks.