Assessment of Clinical Competence in Family Medicine

Medical education prepares family practitioners to work in clinical settings requiring them to weave together strands of new knowledge about human organisms learned by way of assessment in the moment through human interaction with braids of settled expert knowledge built from experience, training, and reading, to generate an expert diagnosis and an appropriate evidence-based plan of action for an individual patient. A multifaceted cognitive performance, such a feat, done well day after day, is the consequence of years of patient, focused, productive participation in academic and clinical settings wherein mentors make teaching moves on behalf of would-be MDs based on their observations of students in an apprenticeship experience.

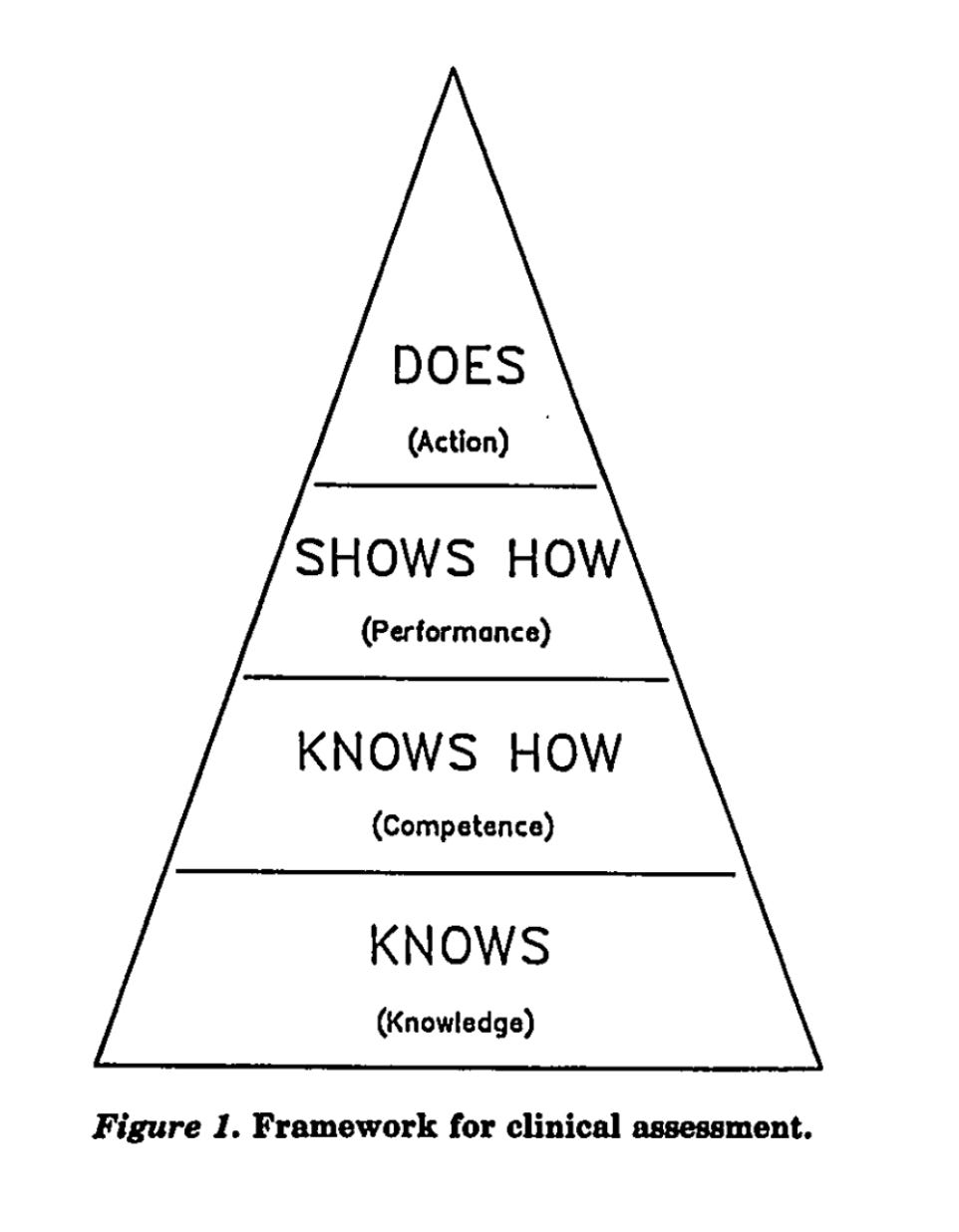

Miller’s pyramid has informed medical educators charged with clinical assessment duties for several decades now (cf. Miller, 1990)1 as a conceptual organizer of the layers of assessment practices required to serve both formative and summative functions. George Miller, MD, was selected to deliver an invited lecture at the 8th annual meeting of the Research in Medical Education group. In his opening remarks, he said the following:

It is worthwhile to think for a moment about why Dr. Miller resisted the invitation to center his remarks on “standardized patients”; making this conceptual adjustment would have dramatically reduced the difficulty of his speaking assignment. He could have focused on a single assessment and avoided the messiness of the real world. But if the need is to know what candidates do and how they do it, standardized patients won’t do. Instead, he forthrightly opened the can of proverbial worms. Witness Miller’s Pyramid:

***

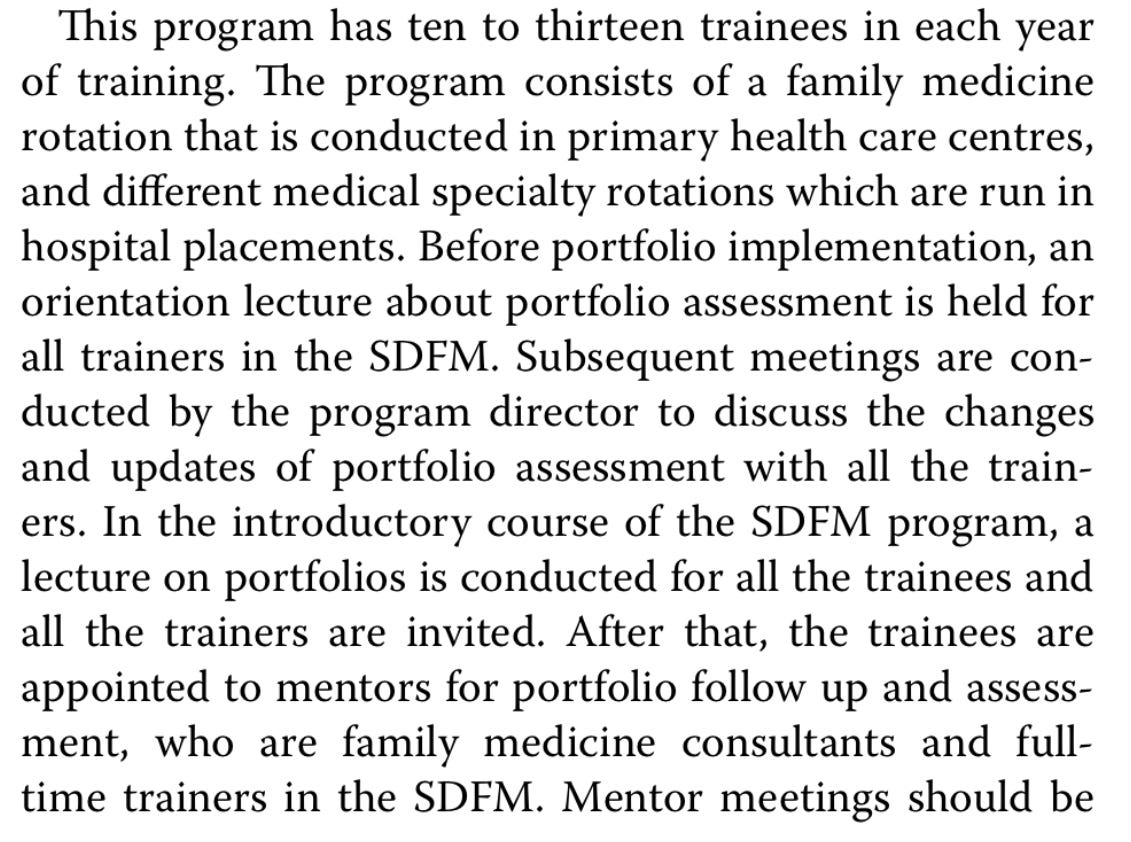

AlRadini (20222) published a piece of research looking at a portfolio strategy as a programmatic approach to formative and summative assessment that takes seriously the peak of Miller’s pyramid. The researcher described a critical shortage of family care physicians in primary care health facilities under the auspices of the Ministry of Health in Saudi Arabia. “The study was conducted in the Postgraduate Centre of Family Medicine at Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, …[and] was carried out in a natural setting to provide a holistic understanding of the experience.” The selection of a portfolio strategy was made for the following reason: “Portfolios in medical education can be used as a learning method to achieve learning goals, as a tool for reflecting on practice, and as a formative or summative assessment of learning.”

Yan and Pastore (2022) discussed quantitative evidence that teaching toward self-regulated learning rather than knowledge and skill acquisition of the variety AlRadini (2022) studied—no standardized patient assumption—would require explicit practices intended to evoke learner reflective analysis. As a result, the Family Medical Practice portfolio designed included expectations that evidence of reflection and of peer assessments would be included together with evidence of regular interactions with a mentor. The ball was in the learner’s court when the role of documentarian was created:

***

Miller (1990) raised all the objections to the standard flaws in standardized tests and measurements, flaws not just in producing invalid findings, but in distorting learning activities. For example, he argued against using Bloom’s Taxonomy as a heuristic to design multiple-choice questions in Family Medicine Education because, while a novice might actually have to do some synthesis to answer a question, a more expert practitioner might simply draw on memory of an experience or an insight. “Patient management problems,” apparently a staple of the times, relied on vignettes of patients to elicit possible alternative diagnoses and treatment plans, but experts often disagreed on the appropriate answers. Well before the rest of the field, Miller called for a genuine focus on the peak of his pyramid:

Faculty members’ clinging to whatever evaluations they feel comfortable with doesn’t always work optimally for faculty in medical education. The same might be said of faculty in public schools. Perhaps a revival of institutional interest in portfolios supporting teachers in making responsible clinical assessments in the moment when deciding on the most promising response to a child in the act of learning could help. As AlRadini (2022) reported, a portfolio strategy embedded in a curriculum for self-regulated learning and mentoring could be a promising administrative response—reaching the peak of Miller’s pyramid.

Miller, 1990. Academic Medicine, Volume 65, Number 9

AlRadini BMC Medical Education (2022) 22:905

https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-022-03991-7