AI Feedback in Mid-Level Writing Classrooms

A Tale of Two Cities

Feedback and Writing

Prize winning music teachers drill into their students two principles. First, practice should never be done mindlessly. Variations in tempo, sustain, and volume as well as notes serve as embodied elements and must be respected, for they preserve the fountainhead of melody and harmony. Listening to oneself perform is more significant than hitting the right notes from a developmental perspective. Listening to recordings of practice is standard practice in music. Listening provides the player with feedback, the proof of how well or poorly the body and its instrument worked in performance.

Writing, similarly, provides the writer with feedback. Instead of listening, the writer reads. Think aloud research from the 1970s illuminated the links between text-to-date and future text as drafts unfold; writing often improves considerably once writers better understand what they want to say after reading what they’ve just said. After writing a bit, a writer reads to find proof of their thoughts in the words.

Self-feedback is a crucial skill good writers develop with varied experiences. In the end it may be what matters most. But writers seek other readers, those who may know nothing or very little about the writer’s plans for the work of the moment, those who are collaborating in a community and cultivate collective growth.

While technological advancements like Learning Management Systems (LSMS), Google Docs, and now Large Language Models (LLMs) have revolutionized the way feedback is delivered in writing classrooms, it behooves teachers to critically examine the nature and functions of feedback itself to ensure these tools truly improve student learning rather than simply streamline text production. Writing to a deadline for production differs from writing to learn to write better. Historically, the quest for efficiency in schooling has tended to overshadow the urgency of strengthening learning outcomes for writing in terms of breadth, specialization, and depth.

Technology has made giving and getting feedback less time-consuming and more immediate. Electricity does more today you know than it used to. Using LMSs and tools like Google Docs, teachers can access student papers at any point during production and comment at will:

“Google Docs is the first online feedback tool I use with my students. I use the highlight and comment tools to ask students guiding questions about their writing. When I highlight a section, I can comment with questions like ‘How does this section relate to your claim in the paragraph?’ and others, and the tool allows students to initiate comments and feedback as well.”

The combination of Google Docs and management platforms takes things even a step further and allows students the convenience of asking their teacher questions about their writing in the act. How many students in high school are frustrated chewing on whether it’s logical to cite the green light across the way as evidence of the claim that the American Dream is actually a nightmare in The Great Gatsby? The salve of teacher feedback readily available lowers the intensity of extraneous cognition as the following example shows:

“Students can highlight sections and ask questions for readers to respond to. When a student asks about cohesion or if evidence and reasoning are enough to support a claim, I’m able to give focused feedback, and I know the student will respond to it because they initiated the dialogue about the text.”

Teachers accustomed to these online tools may be in a quandary. Now, Large Language Models (LLMs) are being touted as magic dust to relieve teachers of this low-level work. Imagine a student has been assigned the task of writing a persuasive essay about The Great Gatsby with the goal being developing a thesis statement on the theme of the American Dream.

The first step for the student, of course, is to write a thesis statement. I remember table talk at a conference in San Francisco where the topic of the thesis statement came up. “Write your thesis statement and then go find evidence,” someone said. “Drives me up the wall." “Sort of the cart before the horse, isn’t it,” someone else said.

What interests me particularly as a teacher isn’t the new AI technology, which is amazing. Savvy students will likely learn quickly the advantages of LLMs in an academic culture that runs on thesis statements, points, paragraphs, and rubrics and speaks in acronyms. The daily media seem to find new evidence every day that kids are routinely using bots to help them write papers. I wonder if the amount of teacher feedback on Google Docs has decreased as the bot gained purchase in the real world?

What can a bot do?

“And what does this thesis have to do with the American Dream?” a teacher might wonder on Google Docs. “Money can’t buy me Love?”

“This is a good start, Paul,” teacher writes. “Keep thinking hard. Try to connect these characters to the theme.”

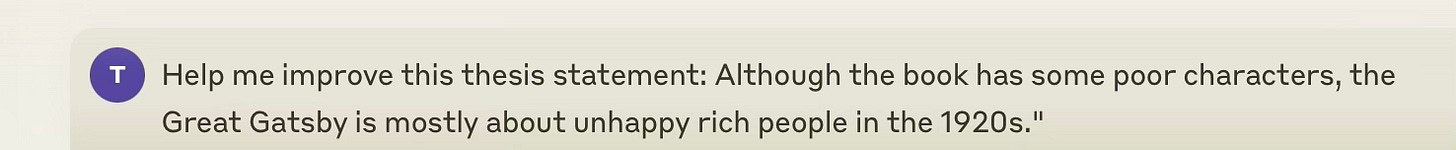

Our insomniac can now get up, get a glass of milk, turn on a laptop, click on Claude instead go Google Docs, and find peace:

No doubt bots provide competition with teachers. Students writing persuasive essays on works of standard high school literature may start with a bot. There is some scientific evidence to support the efficacy of LLMs as useful feedback partners for students on such assignments. The issue I have with it is this: The study was conducted by Turnitin. Teachers as classroom policy authority can decide when and how to use LLMs in writing assignments, and students who use their LLM partners and follow directions as well as the rules will improve their papers from rough draft to final copy. Here is the first paragraph of the online report:

“Feedback is powerful but variable. This study investigates which forms of feedback are more predictive of improvement to students’ essays, using Turnitin Feedback Studio–a computer augmented system to capture teacher and computer-generated feedback comments. The study used a sample of 3,204 high school and university students who submitted their essays, received feedback comments, and then resubmitted for final grading. The major finding was the importance of “where to next” feedback which led to the greatest gains from the first to the final submission. There is support for the worthwhileness of computer moderated feedback systems that include both teacher- and computer-generated feedback.”

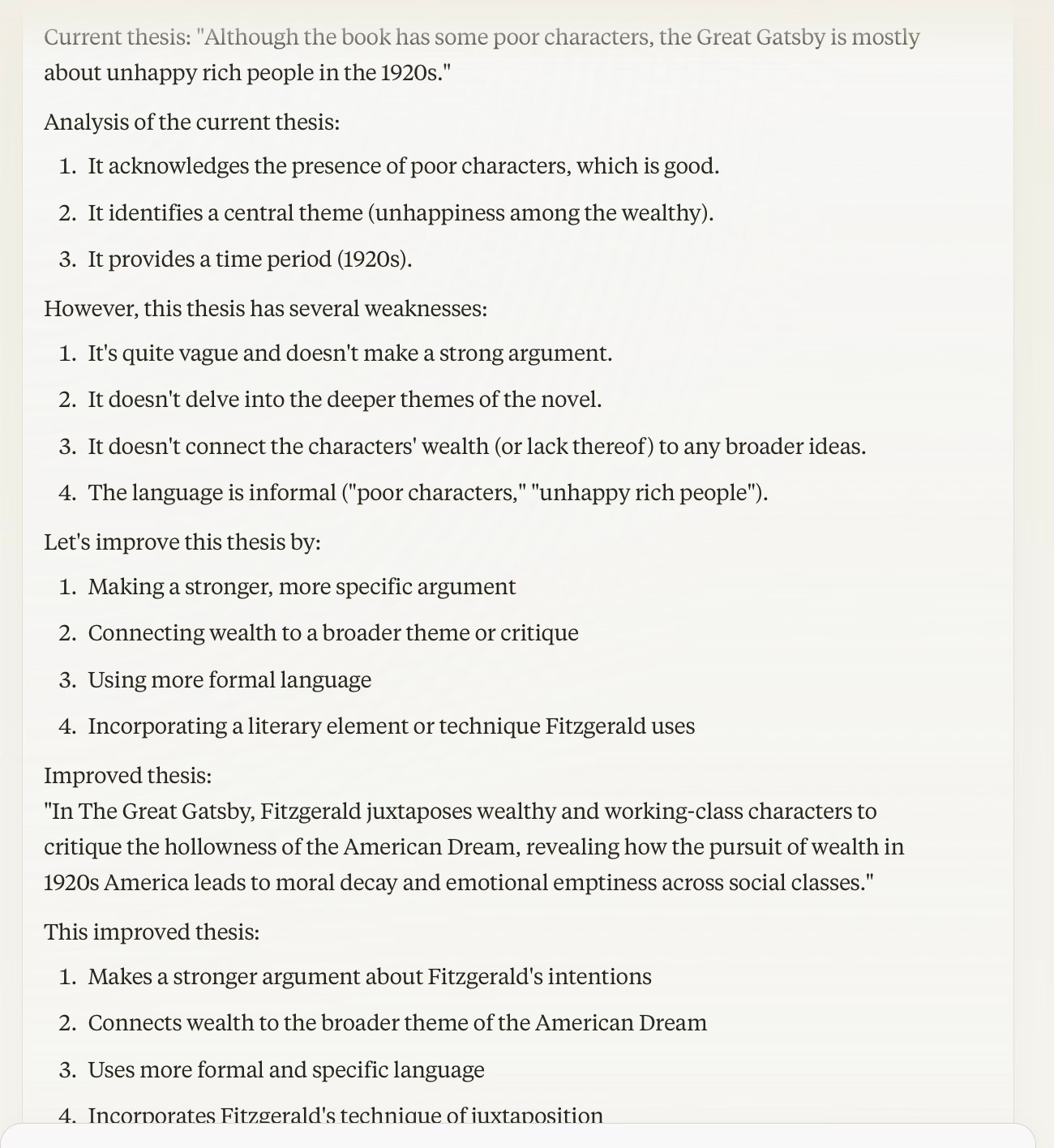

“Where to next?” sounds like a wonderful outcome from a feedback session, doesn’t it? For a busy high school student burning the candle at both ends, a sense of direction and purpose can spark motivation to bring the task to product. This “feedback” studied from the headquarters of Turnitin Feedback Studio was carefully tailored to a theoretical framework of feedback (Hattie, 2007) —we’ll call it the “what next” theory of feedback—which the following figure from 2007 reveals, beginning with a statement of the purpose of feedback. Notice that the self-feedback loop discovered in the 1970s is missing:

Before moving to the next section, I want to raise four issues from what we’ve discussed so far and offer them to you as discussion starters locally.

Nature and Purpose of Feedback: These questions examine the fundamental definition and purpose of feedback in writing education. They ask whether feedback should be narrowly defined as a tool for task completion or if it serves a broader educational purpose. They also explore the relationship between feedback and the overall goals of writing education.

Is feedback in writing classrooms to be defined as information to reduce the gap between a student’s current draft and appropriate completion of a final draft for grading?

Are there more than two ways to reduce this gap?

Are a teacher in isolation and a student in isolation the only agents capable of getting and giving feedback?

Agency and Autonomy in the Feedback Process:

This cluster of questions focuses on the role of various stakeholders in the feedback process, particularly the balance of power and agency between teachers and students. These questions probe the traditional teacher-centric model of feedback and explore the importance of student autonomy and self-direction in the learning process.

Are a teacher in isolation and a student in isolation the only agents involved in getting and giving feedback?

Do students have any say in where they are going?

Is learning to self-regulate the same as learning to follow directions?

Complexity of Feedback: This set of questions looks at the nuances of effective feedback. It challenges simplistic views of feedback as a straightforward, binary process and explores the subtle differences between various types of guidance and their impacts on student learning and development.

Are there just two ways to reduce this gap?

How is “what next” different from an external course correction given by an outside authority?

Is learning to self-regulate the same as learning to follow directions?

Goals of Writing Education:

These questions examine the broader goals of writing education, questioning whether the focus should be on completing specific assignments or developing more comprehensive writing skills and self-regulation. It explores the tension between prescriptive teaching methods and more open-ended, student-directed learning.

Do I agree that learning to write is learning how to complete discrete, prescriptive assignments?

Do students have any say in where they are going?

Is learning to self-regulate the same as learning to follow directions?

Ambiguity of Feedback in Mid-Level Writing Classrooms

Plentiful evidence available online implies that Common Core writing ideology and intentions have fully shaped high school English writing classrooms. References to persuasive goals of assignments are ubiquitous with an alphabet soup of patterned premise and evidence strategies.

Persuasive writing forms the spine of the syllabus and the exam for each of the Advanced Placement courses in English as well. This obsession with argumentation is national and a major complicating factor in the debate about banning bots. Feedback as a concept in writing instruction has narrowed and hardened, and Google Docs with some nicely targeted checklists fill the bill in a world without Al.

To the degree that writing is reduced to the persuasive essay, to that degree feedback is about judging a thesis statement, judging the relevance of a collection of assertions or claims with textual evidence, and judging the effectiveness of a protective shield against counterarguments. The marriage of classical rhetoric and its more modern enabling substructure, the five paragraph essay (give or take a few, as Cicero might say), seems complete.

To avoid the argumentative prism spiraling into mass plagiarism, AI early adopters might open the aperture on the universe of discourse and expand menus to include writing projects in other domains besides persuasion and strategically plan activities to inspire intrinsic motivation to write intentionally and effectively.

In writing classrooms with a broader focus on the universe of discourse, feedback truly takes a variety of forms, not ignoring but certainly not fixated on argumentation and feeding up (redirecting writers) to the goals of the teacher. In writing focused more on the writer’s experiences, for example, establishing a mood and communicating the significance of an experience bring substance to peer conferences asking for feedback on the range of emotions a reader constructs from engaging the draft, say, or on the effectiveness of particular details.

Feedback can be impactful as a teaching and learning tool in active and authentic writing classrooms far beyond its immediate effects on an immediate task. When student writers are metacognitive, motivated and meaning-facing, when they are writing in a community of writers, they crave feedback.

Writers who know what they intend their text to be and do in the reading have invented and negotiated those goals within the parameters of the project. Writers own their memories, but they count on the community to help them shape their text in relation to aesthetic considerations. Writers want to show the community the face of their intended meaning. Readers become mirrors. They write not for themselves, not for their teacher—they write with their community in mind.

I see an inverse relationship in common school writing pedagogy between amount and type of direct instructional control of the persuasive task (DI) and intensity of intrinsic motivation (IM). The higher the control, the more micromanagement of the task, the less intrinsic motivation. Especially when the task is so routine that teachers need not go into detail any more, when students have done it so many times before that they get it already, the song is old, the performance compliance, the motivation “get it over with.”

To the degree that the teacher specifies the form, organization, register, audience, criteria for success, purpose, and topic of a writing project, to that degree the student writer’s intrinsic motivation to shape their own textual artifact shifts violently toward someone else’s intentions, and the writer becomes extrinsically motivated to adapt to the power structure—or not (shrug) and fail. In such communities writers follow directions. In communities of writers, writers shape and create unique textual artifacts in a situated mentorship.1.

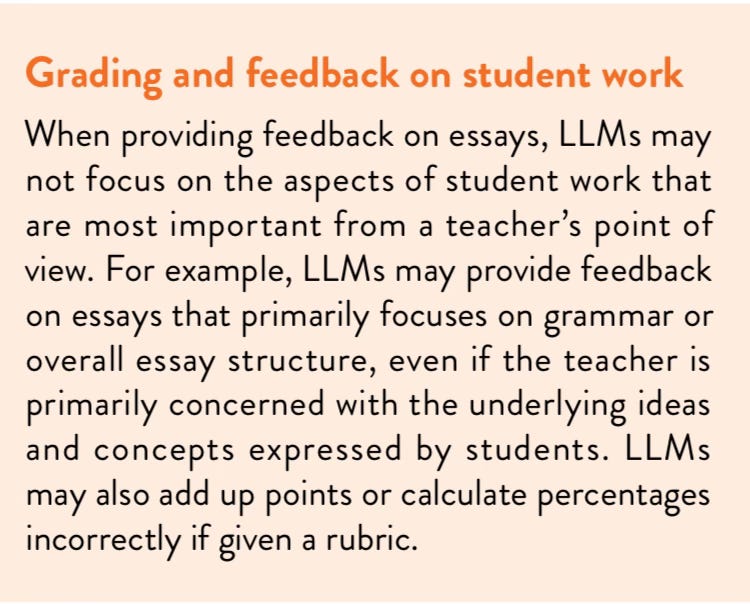

The following excerpt comes from one or another of the flourishing self-help manuals for teachers you can download or buy if you are a teacher working in a school that is experimenting with bots. I took a screenshot at some point and just lately stumbled upon this nugget. Whoever is writing the following paragraph is in the midst of elaborating on the risks teachers’ using AI for feedback face. In this case, the bot may reject the goals of the assignment intended by the teacher. See what you think of this cautionary note:

It’s hard to miss the assumption that the teacher is in control of student thinking. Yet the bot may not attend to what the teacher wants it to attend to. This is an easy fix, however, because bots can be tuned to a teacher’s intentions and provide specific feedback keyed to instructional goals. In the absence of programmed knowledge of the curriculum assignment and its goals, teachers could teach students to write bot prompts individualizing assignment goals for the bot.

This paragraph also conflates feedback with grading, probably because DI assignments make no distinction between feedback and evaluation. The first risk—misalignment of feedback and assignment—is very likely to occur if the bot has not been programmed to apply the teacher’s intentions. The default assumption when using a general bot is this: The user will take the time to contextualize the task for the bot and ask for specific help.

But what about the student’s intentions? When in teacher-centered assignments do students have space for their intentions? The assumption that the only intentions that matter are the teachers can be debilitating in the long run, creating writing dependency. How can students find out whether they did what they set out to do if what they set out to do is never their own intention to begin with? How do they write in the real world a text for a meaningful purpose where they need to have an intention and aren’t likely to get much helpful feedback during the writing?

Blending the words grading and feedback into a conceptual mishmash introduces serious confusion into the relationship between user and bot. The best feedback I can give you as a human being may be critical to your thinking, but it’s never about what I think you must do to pass my class. It is not corrective but my best attempt at giving you what you asked for, which is my reading of your text.

My job as your teacher is to first grasp what you are trying to do and then look around to see where I think you are and where I see you heading, to listen and understand what problem or opportunity you face, to sit beside you in the root sense of the word assess, two heads are better than one, and to give you the benefits of my thinking. I need to know the situation you see yourself in as a writer, not the situation I want you to be in.

The problem with AI used as an amplifier of the teacher’s intentions in any prescriptive DI assignment scheme derives from bot evaluation masquerading as feedback. Evaluation information is not received by students as actionable feedback, which writers take up as food for thought. Feedback in creative and critical work doesn’t foster much thinking about text when feedback is understood as an order.

Checking for a thesis statement, mapping logical links from evidence to claim, and noting a conclusion, or checking for mechanical or usage errors isn’t an act of feedback but one of inspection, an example of a judgment of compliance. As a result, feedback can become conflated with evaluation, with the teacher speaking about the text, not the writing, and the writer listening as a laborer.

Reducing the concept of feedback to a kind of compliance evaluation, a reduction which happens when writing assignments are designed to be foolproof, really leaves no place for student-driven revision as distinct from editing, the most difficult part of learning to write. Revision is where the transformation and the learning happen. Revision is the place where deeper meanings, better ways of seeing, unnoticed nuances, shake loose. People say bots “revise” writing; what bots are doing is reassembling pieces of language. Writers revise their thoughts and meanings and reflect them in text. Writers should face the blank page and make their own decisions.

Student Choice: To Bot or Not

I do see a feedback role for the bot in mid-level writing classrooms—as a considered and purposeful choice for individual writers. If I were advising a community of writers, I think I would tell them to wait to use a bot until they have something resembling a draft of a text, a good enough idea of a draft that they can talk about it with peers, and until they have gotten peer feedback. The writing project needs to have firm roots in the community before writers looks elsewhere. This grounding in the writers self-feedback and peer-feedback early in shaping the agenda of a writing project before considering AI helps make sure each writer has clear, specific, and workable intentions.

Once a project is clear to the writer, at least when the writer has a reasonable writing plan, points at which the bot could come into play begin to blur the line between aesthetics and ethics.

Is what I’m asking the bot to do something I would ask another member of the writing community to do for me? Would I ask a peer to give me three optional ideas for opening my draft? Would I ask someone else to write my first draft?

Would I feel mistreated or disgusted if another writer asked me to do it for them?

Am I wanting to ask the bot because I don’t think I can do it?

Would I be embarrassed by claiming the bot’s output as my own work?

Would I ask another writer to write an outline for me? Would I ask another writer to write a paper for me?

What must writers do for themselves to find their voice as a writer?

How do writers repay their debts to other writers?

How do writers become expert at the craft by becoming more skilled and strategic and learning the tools of the trade?

Botting in a Community of Writers

The field of writing instruction has long talked about the notion of developing a writing community in a classroom. In the context of AI, the time is now to lift developing writing communities to the top of the ladder of instructional goals in mid-level writing classrooms.

Such communities are academic and disciplinary, not warm and fuzzy. Community members expect and even demand regular participation in the community, they rely on other participants for interdependent collaboration. Teachers set the tone for the community by framing the expectations and the deliverables expected for evaluation purposes as the course unfolds.

Writing community goes well beyond being cordial and comfortable together in a group. Scoping out an agenda for a writing project, for example, setting out to write a 1500-word reflective essay about a real or historical figure whom the writer admires, is the author’s job, and to help this writer make sure they’ve thought through the project they consult with peers, log the substance of their consult, and check in with the teacher. At this point the teacher and the writer might brainstorm some ways to approach the bot for background research on a time period, help with drafting interview questions, a search for cultural symbols that might play a natural part in the expository sections.

Interpersonal relationships involving trust, constructive attitudes, shared labor, sensitivity to and respect for the ideas of others, strength to make one’s own choices, transparency in using sources—these are attributes of writing communities which teach processes through experience that lead to learning to write convincingly. Good writing has the stamp of the writer, a stamp the writer and others in the community recognize. Good writers teach their readers how to read them by finding their unique writing powers.

In communities student writers learn to give and take feedback when it is needed in the writing process. As Nancy Atwell taught us, the need for feedback occurs when writers sense either a problem with the writing or an opportunity to change or invent, accompanied by uncertainty and questioning. Before calling together peers for a writing consult, writers are prepared to explain what they need from their peers in the form of clear questions. This same preparation should be done in advance of sessions with AI.

A Path Forward: Foregrounding Feedback and Revision as Learning Outcomes

Writing teachers and learners in the trenches will find inherent weaknesses in the notion of a bot as a reader or a writer like a human. Such is just not the case, but it may take considerable experience using bots in authentic writing situations to come to this conclusion. One path forward involves clearing away structural and formal learning objectives rooted in texts as finished products. Using rubrics to shape a writer’s conception of what is possible within a writing project is tantamount to focusing on product from the beginning. With a writing prompt and a rubric—two product tools—savvy students can prompt and manipulate a bot to hit the jackpot.

But what if the outcomes teachers want to emphasize are active process goals? Instead of a rubric spelling out the attributes of a top-notch paper, why not a rubric spelling out qualities of effective feedback on the giving and getting end of a peer or teacher consult? Why not a learning log requirement for teachers to assess giving and taking feedback as a writer? Why not a reflective memo requirement—one per week—characterizing work done with a bot that week, a reflective memo shared in community before going to the teacher?

Another learning outcome important to earning credit for the course is revision. To conceptualize writing consistent with research in the field dating back sixty years or more, revision qualifies to become a bona fide learning outcome. How many writing teachers using a steady diet of persuasive writing assignments can talk in detail about where writers in a community are developmentally in terms of performance during revision?

Indeed, the future of revision is already here at the University of Madison, Wisconsin. Consider the following reminder for writing professors published on its Writing across the Curriculum webpage for professors:

“Revision, revision, revision: the term is nearly a mantra in Comm-B and Writing-Intensive (WI) courses. Indeed, the university criteria for Comm-B and Writing-Intensive courses mandate that instructors build the revision process into their courses—and for good reason. Research has consistently shown that the best, most experienced writers regularly revise their writing in substantive ways.”

Unsurprisingly, according to U Madison professors in charge of the writing program, instructors of Comm-B and WI courses complain that the most difficult aspect in teaching these courses is student resistance to revision. They routinely find that students make few changes to drafts, and if they do, the changes are superficial. At first, those in the know concluded that students resisted because revision is demanding work. After reflection, however, their revised conclusion is this:

“Some students may not meet our expectations for revision because they understand the term very differently [emphasis in original] than we do. When Nancy Sommers, a researcher at Harvard, asked student writers and professional authors what “revision” meant to them, they gave her wildly divergent answers…”

This sort of information ought to inform every high school’s discussion of its writing program—including writing across the curriculum if it exists—to embrace the existential complexity of writing in the real world, including the expansion of feedback and revision to become separate learning outcomes worthy of formative and summative assessment.

How do students at U Madison view revision? “…[J]ust using better words and eliminating words that are not needed,” one student at UMW said. “I go over and change words around.” Such a statement about revision, as we know from the work of Lucy Calkins, is a characteristic of upper elementary students’ developmental phase as revision experts. “…[C]leaning up the paper and crossing out,” another said. “It [revision] is looking at something and saying, no that has to go, or no, that is not right.”

The problem with this understanding is its conflating of language and thought. Changing words around isn’t writing. Crossing out and saying no isn’t writing. Tinkering with words at the surface of the text is good evidence of a novice in terms of revision. The topic of revision is book length, and writing teachers should have solid knowledge of theoretical and empirical research on it.

Verbal thought/intelligence is a specific construct in psychological literature. Whether thought is possible without language or language is possible without thought is a philosophical problem teachers really don’t need to engage, in my opinion. But inside our brain is a thinker and a speaker; thought pushes the speaker, the speaker pulls thought, and the writer puts it all down in words. The act of verbal thinking is unique to each writer. The effort to put thoughts into words is hard, doubly hard when the task becomes re-”visioning” what has already been stabilized in print, which I think of as “reverbalizing.” Supplanting verbal thought by doing it for students is the bot’s most profound risk.

One high school teacher from the East Coast wrote an editorial to the English Journal in 2010 to express how comfortable students and teachers alike have become with easing demands on verbal thought to make writing and its evaluation more efficient:

I have but one quibble with this editorial. The use of the formulaic essay grounded in a single controlling idea and iterations of paragraph structures does eliminate the “responsibility [of students] to make decisions about form and organization,” but it also eliminates the opportunity to discover form and structure of ideas inherent in the subject matter, a challenging task which good writers struggle with very early in the writing process. Finding the form and structure of ideas in the content, I would argue, is verbal thinking at a higher level, the kind of work flow charts and Venn diagrams can support. Whether teachers believe they are accomplishing something with five-paragraph essay assignments is an open question. I am curious to know empirically what teachers are thinking.

Democratizing Critical Thinking

Consider a writing assignment one might give in a junior year writing class. Suppose students were asked to select a pre-identified theme in the novel The Great Gatsby. Suppose the theme one student selected is “the American Dream.” What would the next step in the formula be?

Teachers use standard heuristics or formulas as tools to teach writers to write a thesis statement. (Inside the Mind of a Student Writer: ‘Although X, Y’ would work, but it’s worth only 5 points. Although some say Gatsby is a love story, it is really about the American Dream. ‘Specific Claim So What?’ would be great, and it’s worth 7 points. Gatsby's obsession with recreating the past shows how weak the American Dream is, how harmful nostalgia can be. Hmmm… Oh, yeah, the if-then thingy, but I don’t think she likes it… can’t remember how many points…) The pinnacle skill in this mindset is, not surprisingly, the performance of writing a quality thesis statement (from the Turnitin Study cited in the intro):

“Respondents… rated feedback on thesis/development as the most valuable, but reported receiving more feedback on grammar/mechanics and composition/structure (Turnitin, 2013). Turnitin (2013) suggests the disconnect between the receipt of general, overall comments compared to the perceived value provides further support that students value more specific feedback, such as comments on thesis/development.”

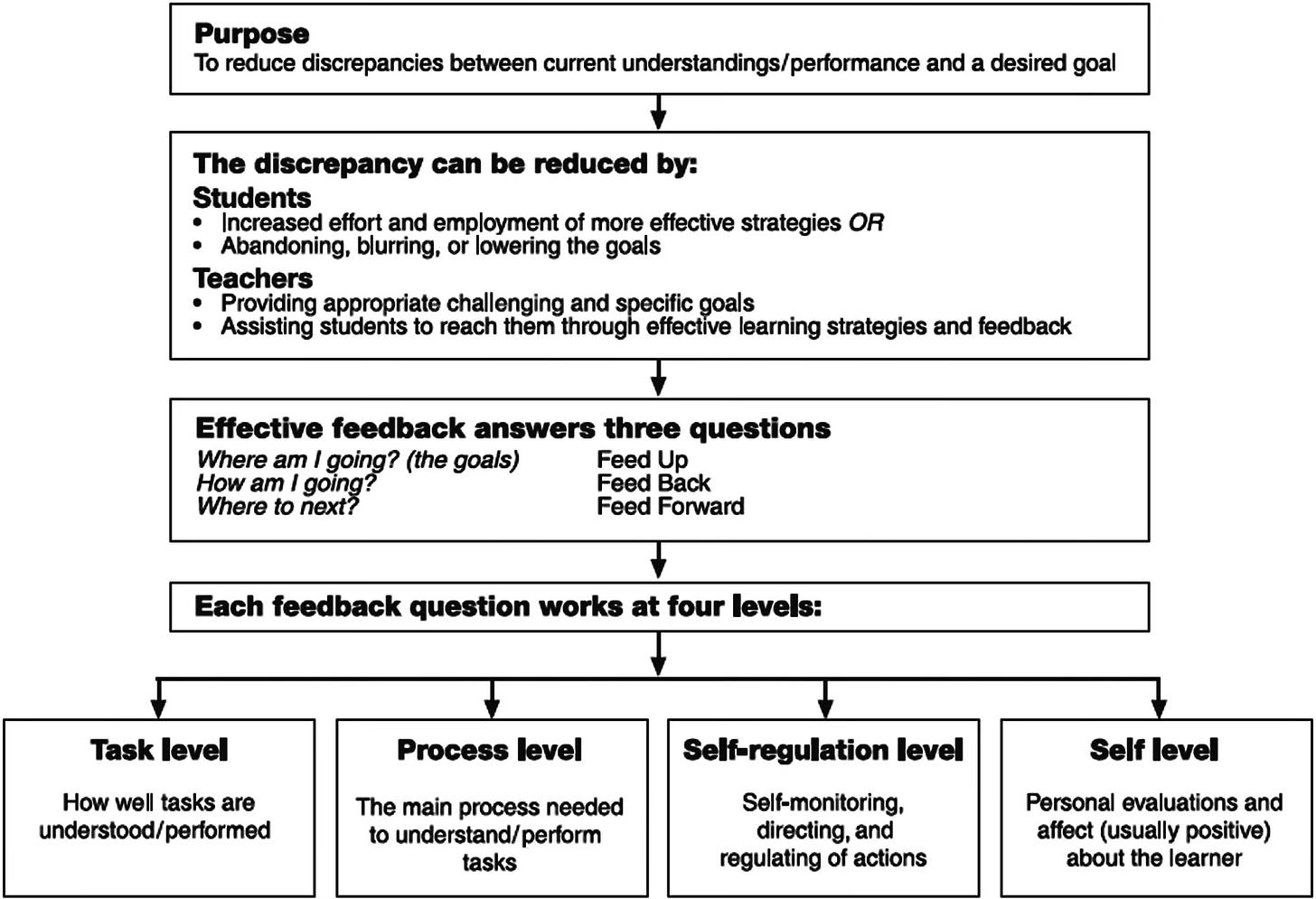

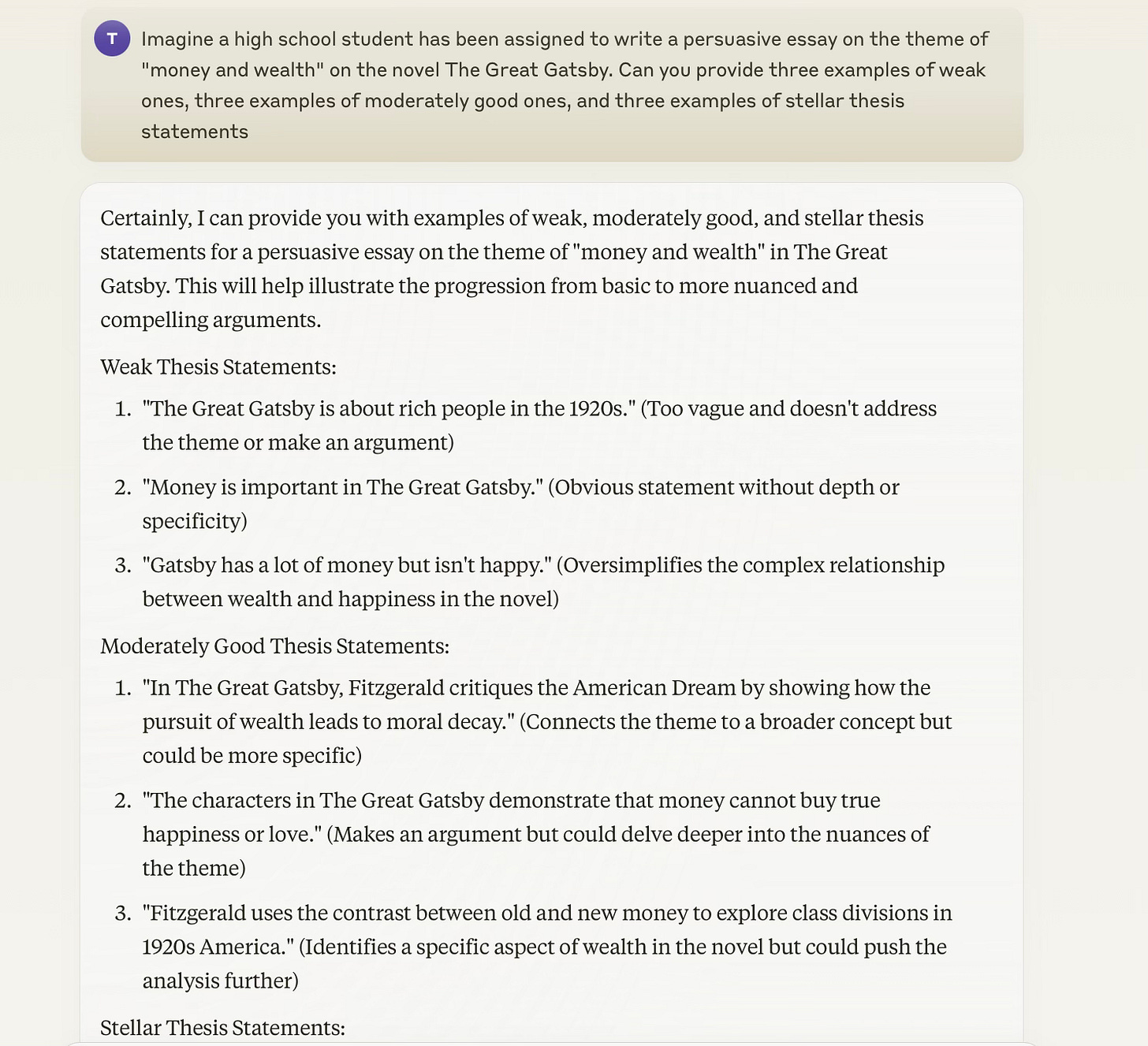

I asked the bot to provide examples of different levels of thesis quality. The result suggests that the bot can clearly accomplish the delivery of a stellar thesis statement on demand:

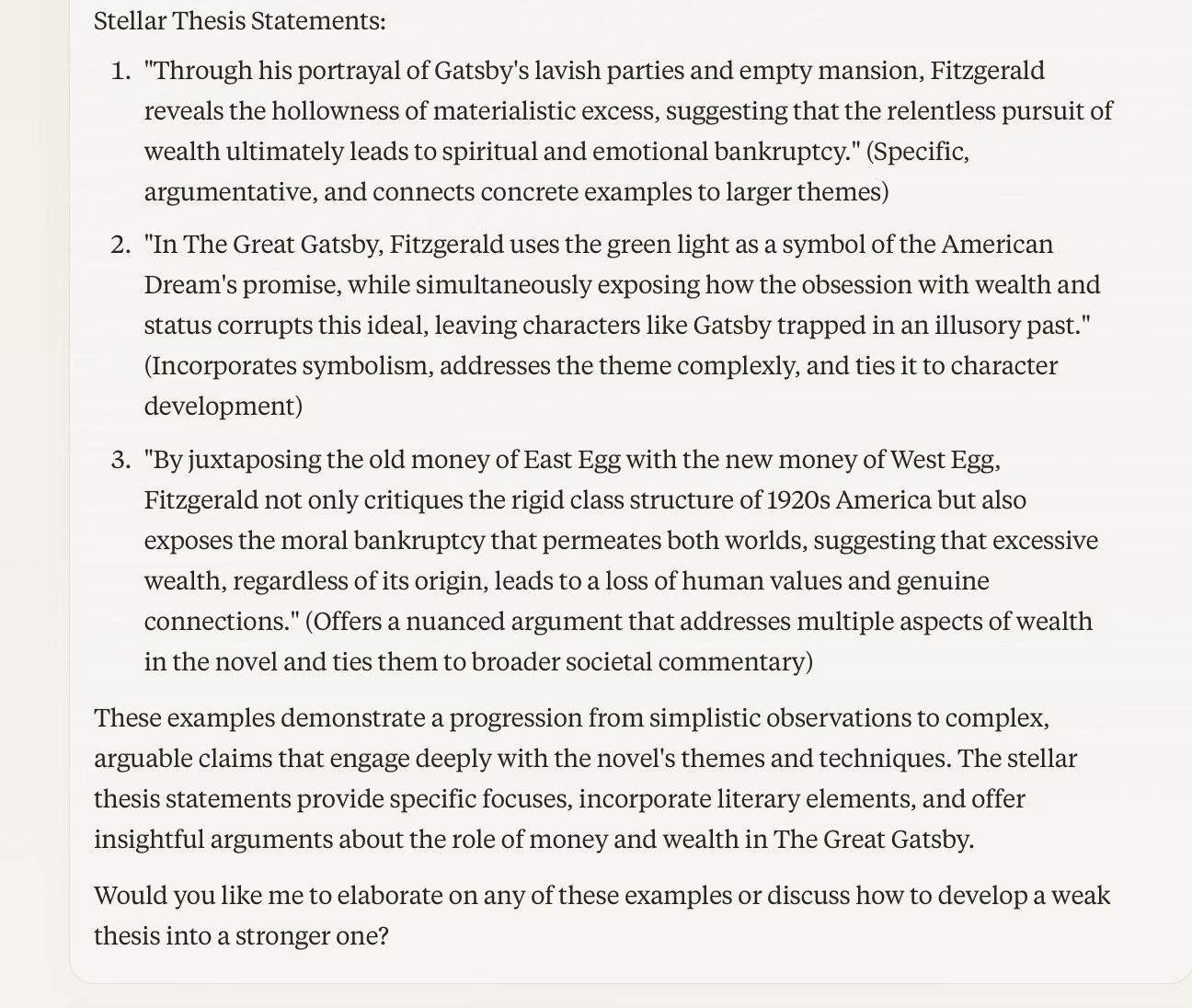

Much of the fear of AI, I fear, is related to teachers’ concerns about learning losses of critical and creative thinking skills. Make no mistake: AI can do what teachers are asking students to do under the banner of English Composition in the name ofd persuasion. But the idea of critical thinking has become narrowed and fragile to align with the argumentative mindset. In my view, critical thinking is defined differently the closer its enactment to reality. I’m not suggesting this view ought to be your view, but bear with me. Think of this as a Venn diagram (my creation):

Fears of AI can be mitigated by stepping back and looking at CT in relation to a young human life who has, after all, hopefully decades ahead with AI on the scene. SCT is defined by disciplinary communities of practice, fundamentally altered forever by AI. GCT is defined by institutional agents and organizational entities in harmony with academic and professional structures. SCT needs updating constantly, GCT needs recent and relevant challenging experiences with current complex problems and inquiries, ECT is used in extra-disciplinary settings where disciplinary expertise may or may not be relevant.

At each level of CT, the core of the active agent is I, human—with or without AI. Writing within a discipline, writing within an academic institution, and writing in the real world change the level of logic and certainty required to make a decision from documented logical analysis, to situated predictable guesses. Within this scheme teachers still can locate the persuasive essay assignment.

The Universe of Discourse

James Kinneavy’s theory of discourse was groundbreaking in 1971. Theorists looking for a breakthrough in translating classical theories of rhetoric into modern theories held out great hope. The rhetorical stance Aristotle and his cohort of philosophers came up with to guide invention, organization, style, and memory for persuasive speakers rhapsodizing in democratic courtroom—subject, audience, occasion and purpose—was reduced to a five-paragraph structure during the Industrial age, but little of substance had changed. We still had the argument and the body paragraphs.

Kinneavy changed the question. Where Aristotelians asked “What should writers be thinking about as they prepare for public debate?” Kinneavy and others began to ask “What are writers actually thinking about, what problems do they run into, when they are writing across the universe?” Kinneavy and Aristotle went to dinner together one night with Janet Emig and the writing process approach was conceived. Writing and reading theorists alike began to shift from a homogenized view of readers and writers as cognitive windup toys set in motion by a teacher’s directions to a multifaceted view of readers and writers as agentic participants in social events and experiences involving texts.

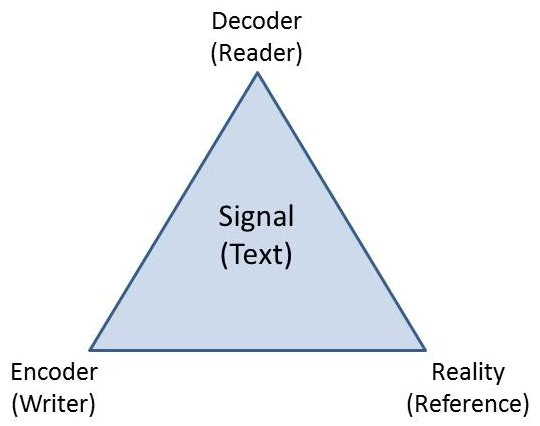

Fifty years later, of course, Kinneavy has been taken to the cleaners, challenged in every nook and cranny for its structuralist, reductive foundation, slowly rehabilitated as interesting if nothing else, and still his framework resonates as a heuristic. Together with the theory of aesthetic reading distilled in 1938 by Louise Rosenblatt, Kinneavy’s Triangle provides a rack to hang your hat on during these wild days of AI in classrooms across the spectrum. As others closer than I to the heart of the action have written, fear has exploded in school buildings and on college campuses. Places to hang a hat are sorely needed.

Kinneavy’s map of the universe of discourse was used during the era of authentic assessment designs as an anchor in large scale assessment to insure that all varieties of reading and writing are taught and sampled. I learned about Kinneavy when I was a member of the group of teachers selected to work on the design team for the CLAS reading test in California in the 1990s, the first statewide measure of reading using student written responses instead of multiple choice items. The turn toward persuasive writing pursuant to the Common Core rendered Kinneavy largely irrelevant (there has to be more than one text and one purpose in a universe), but the threat of Large Language Models in writing instruction could be better addressed from revisiting Kinneavy’s following diagram:

This triangle provides a tool for talking about where and how a writer’s focus might be as the writer works on projects across the universe of possible projects. In the center of the triangle is the “T,” the text under construction. Inherent in any writing task is figuring out what sort of T would most effectively serve the writer’s intentions.

Suppose a writer’s focus is squarely on the T. When writers craft poems, plays, stories, novels, etc., when the intention is to produce an aesthetic artifact without concern for reality, for the author as biographical figure, or the reader as a consumer, such writing processes implicate creativity, imagination, use of figurative language, use of language as a set of aesthetic tools, and the like.

The T in the triangle is moveable. As it floats toward R1 (reality), the writer focuses less on sculpting a beautiful text from words and more on the relationship between the text and reality. An imaginative writer telling a story about the experiences of a homeless child, for example, may need to learn about the reality of such lives. A historical writer writing a novel about growing up in poverty in Appalachia may need to read a great deal about the setting and produce a text with verisimilitude. A sociologist writing up a study off the effects of homelessness on the education of rural students in America faces a different set of learning activities, including reliance on situated critical thinking strategies.

As the T floats to R2, the reader, writers first faces the task of defining for themselves what they understand about the audience and its attitudes, its knowledge base, and its beliefs and values. Before the writer can decide what content to consider, the writer must envision how the audience might respond. If the intent reaches beyond evoking a particular response to persuading a reader to act, general CT, the thesis statement, and the principles of argumentation come into play. Advertisements, political speeches, editorials and the like exemplify the kinds of texts available to the writer.

Writing with a focus on the writer is shaped by the position of the T with regard to Reality and to the Reader. For example, as a literary text (centered T), memoir gravitates between the center and the W corner, influenced by attention to the response the writer aims to evoke from a reader. If the focus on the writer were more pragmatic and persuasive—a college entrance essay, a cover letter applying for a job—a different set of writing strategies and an ask for a different kind of feedback could be important. The text under production shares a need for narrative substance about the writer and a persuasive holistic effect that compels the reader to say, YES.

Suppose a teacher builds a course around the requirement that each student develop, complete, document work processes in a log, and publish in community and online five writing projects, each the equivalent of 1500 words. One project must gravitate to the T, one must flow toward the W, one must focus on impacting the R2 (the reader) in some way, and one must report factually about reality. The fifth is a free choice.

Each project is graded through writer-teacher negotiation using a community-negotiated rubric with consideration for qualities of the written products, through evaluation of reflective memos and process logs, evidence of revisions from drafts and logs, a final self-assessment statement capturing major insights about writing from the work and goals for future learning. This final statement ought to be accessible to the community of writers and avoid any references to a letter grade.

Teachers who are already experimenting in their classrooms even if in a regime of persuasive essays are better positioned than I to speak about specific bots, specific applications, and technical issues. English Departments as wholes would do well to collaborate in professional inquiry groups to understand the ways students use the bot and how those ways add value to the writer’s expertise, not just to the writer’s products.

My intent here is not to idealize nor romanticize writing instruction. Students in intermediate writing classrooms must write, for example, and there are deadlines. There are non-negotiables, an adult in the room. Students must learn that in the real world writing is indeed graded, and teachers are obligated to make this message clear. Doesn’t mean they have to use grades to motivate students. Like every other handmade human product, texts come in varying levels of worth, ranging from exquisite philosophical, scientific, or aesthetic texts to mundane utilitarian texts often with an expiration date, from The Waste Land to a grocery list. Giving students explicit directions from the start of the trip with a rubric as GPS might guarantee a safe and timely arrival. So what? They had a nice experience? What did they learn?