Writing with Commitment: When Attention Becomes Intention

The Paradox of Caring

Writing is sometimes hard if you care about it. The paradox is that the more you care about your writing, the more difficult it can be to get words on the page. When a writer is invested in the outcome, several things tend to happen.

The internal critic gets louder. Writers start second-guessing word choices and sentences before they're even written. The stakes feel higher; if we care about the result, each decision carries more weight. We become more conscious of the gap between what we want and what we're actually producing.

But caring is also what makes writing meaningful and worth doing. The challenge is to find ways to quiet that literary critic during early drafts while sustaining a high level of self-investment. We will return to this challenge in the conclusion.

The Mechanics of Not Caring

Writers who don't care about their writing exhibit several distinct patterns. They often write quickly and breathlessly, treating their work as a mechanical transaction. You can see it in their word choices—the same cliches appearing again and again, no nuances, little complexity.

These writers rarely revise except to fix obvious errors. Why would they? The writing is a means to an end—meeting a deadline, filling a word count, earning a grade or a paycheck. They don't lie awake at night wondering if that metaphor in paragraph three really lands, or if their ending made an impact,

There's a lifelessness to such prose reminiscent of AI output. The sentences are often stale, wordy fluff covering up sparse information, going through the motions of communication without ever revealing a person at home behind the words. The writer remains safely distant from both subject and reader, handling ideas like bulk objects to be cataloged, potatoes stored in a cellar.

Yet even here there's an odd sort of craft—the skill of writing without vulnerability, of producing text that fills space while saying as little as possible. It's the literary equivalent of small talk, words that fill silence without disturbing the peace.

The tragedy isn't that such writing exists. There are always tasks that require simple documentation or basic information transfer. The tragedy is when writers capable of much more choose this path out of fear or fatigue or the grinding pressure to produce.

Think about SEO-driven articles where the goal is simply to fill space with keywords. An SEO-driven piece of writing is one that's created to rank well in online search engine results rather than to serve readers.

Deliberate repetition of specific search terms (like "best coffee makers 2025" or "how to fix a leaky faucet") at a calculated density is done to get eyeballs on text without regard for the text itself. Headings and subheadings crafted around popular search phrases rather than natural language, and content length determined by SEO metrics rather than what the topic needs, produce shallow coverage of many related keywords rather than deep exploration of ideas.

The irony is that modern search engines have become sophisticated enough to recognize and sometimes penalize this kind of mechanical writing. Yet there's still a huge industry built around producing it. Writers may plagiarize or recycle content without concern for originality or authenticity.

Finding the Sweet Spot

I wonder if true "not caring" about writing is as common as it might seem. Even writers doing apparently mechanical work often care about something: meeting deadlines, getting paid, maintaining a professional reputation. The “not caring” might just be directed at making throwaway texts. Who has time to doodle and noodle?

This raises an interesting question: Is it possible to find a middle ground between paralyzing care and complete detachment? Is it possible that writers must write throwaway texts to get to texts of lasting value?

Perhaps the sweet spot is caring deeply enough about the core purpose of writing to spend time and effort early in the process, exploring, experimenting, knowing the work produced during this phase may not survive.

Something important to the writer has to gain the attention of the writer—an invitation, an opportunity, an inspiration. These are the times when learning to write happens.

The Embodied Nature of Writing

This heightened attention to the task environment is deeply embodied. A phrase might come with a physical sensation, a pang of hunger. An idea might manifest first as a rhythm in the body, a catch in the breath, or a shift in muscle tension—and become thought. I may be waiting in line at a bank and pull out my phone to catch the idea I just glimpsed in makeshift words in a note.

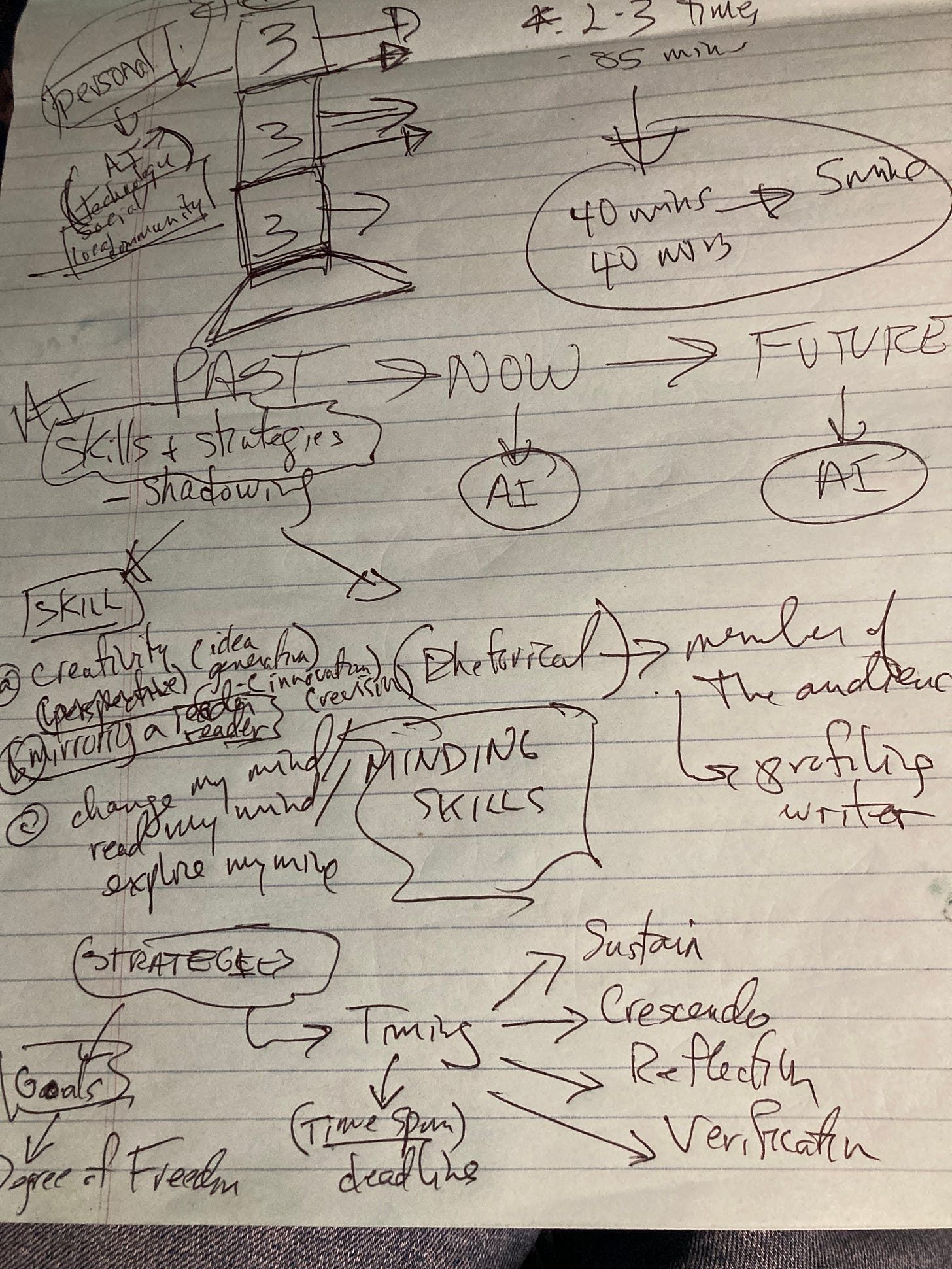

The beginning of writing is for me, especially in later years, often felt before it is a thought. My attention, opened fully, transforms into a drive to explore, an urge to find out what I really think, and after handwriting what I know to be throwaway drafts or half-finished maps, my attention begins to narrow into an intention. When I sense an identifiable intention, that’s the time I might begin exploring topics and issues with a bot.

I’ve come to the writing of this post because I wrote my way into understanding an idea about prewriting anew. I am compelled to grasp this idea in its complexity and work to explain it because I am invested in it now. I want to share it with any interested reader not to put a feather in my cap, but to participate with others in helping to meet the moment of AI.

The Problem with Classroom Writing

What marks the beginning of a writing project in many classrooms? A writing prompt? A writing assignment? Constraints on what can be written about, at what length, in what format?

The parallels between traditional classroom writing and SEO writing are striking. Both often prioritize form over authenticity, mechanical execution over genuine exploration.

In many classrooms, writing begins with artificial constraints: A thesis must appear in the last sentence of the first paragraph. Don’t write in the first person. Imagine this audience. Include specific quotes from the text as evidence for your inference. Minimum 1000 words.

This mirrors SEO writing's rigid formulas: Include the keyword every 100 words. Break text with a subheading every 300 words. Link to 3-5 other pages. Front-load key terms in each paragraph.

Both systems teach writers to start not with an idea or question that draws their attention, but with an external framework to be filled. The result is often writing that feels manufactured rather than discovered. Students learn to reverse-engineer essays just as SEO writers reverse-engineer search rankings.

The deeper similarity is how both approaches can drain writing of its exploratory power. When you know exactly where you're going before you begin, whether it's to satisfy a rubric or an algorithm, you're less likely to stumble upon unexpected insights or follow promising tangents. The writing becomes less an act of thinking and more an act of assembly.

I don’t mean to say that structure and constraints are inherently bad. They can be incredibly useful tools. But when they become the primary driver of the writing process, something essential is lost. The question becomes: How might we introduce students to writing forms while preserving space for genuine inquiry and discovery?

Human Attention vs AI Processing

AI attention has no such preliminary attention state and, for me, is pretty much useless as a muse. Other writers have found it helpful in a carefully prompted exploratory mode. AI begins processing immediately when prompted without this crucial phase of human embodied receptivity. Prompt, prompt, prompt. AI can't experience that liminal space where ideas first start to coalesce.

Synthetic attention is always "on," always operating at full analytical capacity, which paradoxically makes AI less capable of the gentle, indirect, tickle of attention that often yields the most original human insights.

Human attention is not a spotlight, highlighting and abstracting snippets of experience, or a filter, letting some perceptions in, turning away unwanted sensations. Attention is deeply woven into our entire conscious and unconscious existence.

It's an oscillating force that ebbs and flows through different states of consciousness. Even when we "lose" attention in sleep, a form of it continues working, processing memories, maintaining basic awareness of danger signals, and weaving dreams.

What makes human attention distinct is its profound integration with our biological rhythms and survival needs. It dims and brightens with our circadian cycles, is colored by our emotions, and is shaped by our need to survive and connect with others. It's not just about focusing. Being alive to the world in a particular way at a particular moment—that’s attention.

Without genuine attention there can be no genuine intention. Without genuine intention, writing is just too damn hard, and the payoff isn’t enough.

Moving Forward: Protecting the Human in Writing

We need to protect and nurture this pre-writing state in human writers, especially now when AI can produce text so quickly. Assignments can honor embodied prewriting experiences if not through actual movement in the world, then through collaborative face-to-face discussions.

Rather than give students a cookie cutter prompt, give them a choice: Write 1,500 words on a topic of your choice related to the syllabus over the past three weeks. Your work may be narrative, expository, or persuasive. You may write creatively, you may research and cite sources, you may interview others and build your paper from what you learn. But your intention must be clear and fulfilled.

Students need to understand that good writing often begins with what might not look like writing at all—with walking, daydreaming, or seemingly aimless observation. This time is not wasted time but essential creative preparation.

Writing exists on a continuum from our most private inner speech to our most public meta-writing. At its start, writing emerges from pre-linguistic thought, from those fragmentary impressions and feelings grounded in lived experience that precede words. This is territory that artificial intelligence cannot enter, no matter how sophisticated its language processing becomes.

As these private thoughts move toward externalized speech and then into proto-writing, they begin taking on permanence and conscious shape. This is where caring about writing first manifests, in that delicate transition from personal meaning-making to crafting something that can reach others.

The challenge for writers isn't just technical skill but maintaining that authentic connection to their original impulse while engaging in the increasingly conscious work of revision and refinement.

Growth in writing may lie in learning to move fluidly between these states, from the embodied attention that sparks ideas, through the messy exploration of early drafts, to the careful crafting of final text.

Practical Strategies for Teachers and Writers

Silence the Inner Critic During Drafting: Create a dedicated “freewriting” phase where students focus on generating ideas without editing or self-judgment. Set a timer for 10-15 minutes and write continuously, allowing thoughts to flow unfiltered.

Balance Structure with Exploration: When teaching or practicing writing, start with open-ended prompts that encourage inquiry and discovery. For example, instead of rigidly defined essay formats, allow flexibility in topic choice and structure to foster freedom of expression.

Leverage AI as a Tool, Not a Crutch: Use AI tools for refining drafts or brainstorming but delay their use until after the initial creative phase—or at least until writers have demonstrated a shift from interest and attention to an intention. This intention can ensure that your writing retains its human originality and depth.

Revise with Purpose: Treat revision as an opportunity to align a draft with a core intention. Focus on clarity, staging, nuance, and emotional resonance rather than simply correcting errors.

Encourage Reflection in Writing Education: Design assignments that prioritize personal engagement over formulaic output. For instance, ask students to reflect on how their chosen topic led to their intention and connected to their experiences or interests.

By implementing these strategies, writers can navigate the tension between caring deeply about their work and avoiding creative paralysis, ultimately producing writing that is both meaningful and impactful. These experiences, even if rare, can have lasting effects.