Everyone seems to be asking the wrong question about AI and writing. We hear endless debates about whether large language models will ruin student writing, make assignments meaningless, or replace the work of teachers.

But thirty years ago, in an era when today’s tools were barely imaginable, we studied something that now feels incredibly relevant: how students’ writing problems change as they grow. What we found then reframes the debate now, several decades apart.

The real issue isn’t whether AI changes writing instruction. It’s whether writing instruction can continue to create problem-rich environments where students develop as thinkers, not just as producers of text.

Writing as problem-solving isn’t just a theoretical stance. It’s a practical instructional approach that transfers across every text students will ever compose. The beauty of this perspective lies in its universality.

Whether students are drafting lab reports, college application essays, or workplace communications, they’re fundamentally engaged in problem-solving work: figuring out what to say, how to say it, and whether it achieves the desired effect.

This framework gives teachers and students a shared language for talking about writing. Instead of mystifying the composing process or reducing it to formulas, we can ask concrete questions: What problem are you trying to solve? What have you tried? What else might you try? What’s working and what isn’t?

For teachers, establishing a writing assignment means identifying a substantive problem to place before learners—not a topic, but a genuine rhetorical challenge—and then working collaboratively to help students develop their own solutions.

For students, learning to identify and articulate writing problems becomes a transferable skill that serves them long after they leave our classrooms. Teaching students to recognize what kind of problem they’re facing, and what strategies might address it, transforms writing instruction from a series of disconnected assignments into a coherent developmental progression.

The Portfolio Method and Assessment Structure

Sandy Murphy, my major professor for my dissertation, and I wanted to see whether we could find evidence that this problem-solving approach could actually develop more sophisticated writers over time.

We worked with middle school English teachers who implemented portfolio-based instruction across three trimesters. Students compiled portfolios at the end of each trimester, selecting artifacts that represented their work during that period.

The portfolios weren’t just collections of finished essays that had been graded. They were ongoing occasions for structured reflection and assessment by examination committees of local English teachers.

The key instructional move was requiring students to write “entry slips” for each compartment of their work. These entry slips asked students to contextualize their work—explain the impetus, describe their process, and most importantly for our purposes, characterize the types of problems they faced during that grading period.

This wasn’t freeform journaling; it was guided reflection that made students’ problem-solving processes visible and analyzable. Students knew that the examination teachers would take into account the quality of their reflections when they rated the overall collection.

The assessment structure created several important conditions. First, students received regular informal feedback on their reflections throughout the trimester from their teacher and peers, helping them develop more precise language for describing their writing challenges.

Second, the portfolio format required them to demonstrate learning across sustained time periods, not just produce isolated successful pieces. In fact, students discussed writings they struggled with and failed to achieve the vision they had for them.

Third, because examination committees evaluated growth and learning rather than just polished final products, students had permission to take risks and work through genuinely difficult problems.

Data Collection and Analysis

From a corpus of 600 middle school portfolios, we selected 12 focal students randomly and analyzed their complete portfolio sets—beginning, middle, and end of year folios, yielding 36 portfolios total. We specifically focused on the entry slips where students described the problems they encountered while writing.

Our analysis used the constant comparative method (Schatzman and Strauss, 1967), starting with open coding to identify what students were actually saying about their writing challenges. We read through entry slips multiple times, noting every distinct problem students mentioned.

Initially, we had dozens of preliminary codes—everything from “couldn’t think of anything” to “wanted to make readers feel sad” to “my mom said I needed more examples.”

Through axial coding, we collapsed these preliminary codes into broader thematic categories that captured conceptually related problems.

We tested our coding scheme by independently coding a subset of entry slips, comparing results, discussing discrepancies, and refining our definitions until we achieved reliable agreement.

The final coding scheme represented distinct types of writing problems students identified, ranging from basic execution concerns to sophisticated rhetorical challenges.

What the Data Reveal

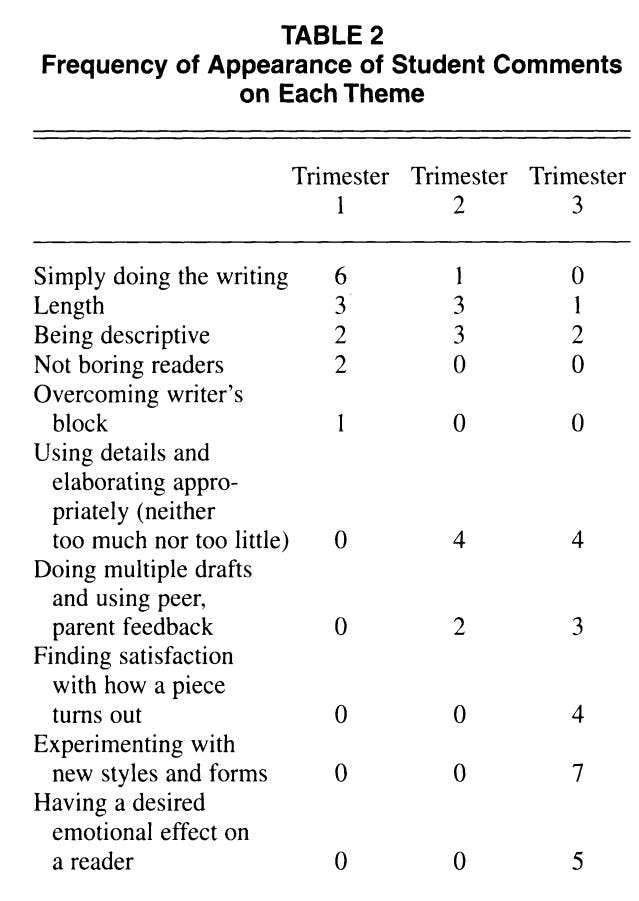

Table 2 above shows the frequency with which different problem types appeared across the three trimesters. The developmental pattern is striking and tells a clear story about how student writers mature when problem-solving is foregrounded.

Trimester 1 reveals students preoccupied with fundamental execution. Six students identified “Simply doing the writing” as their primary challenge—getting started, producing text, overcoming inertia.

Three worried about “Length,” meeting word or page requirements. Two focused on “Being descriptive” and two on “Not boring readers.” One student mentioned “Overcoming writer’s block.”

These are survival-level problems. Students are asking: Can I do this at all? Can I produce enough? Can I avoid obvious failure?

Trimester 2 shows significant evolution. “Simply doing the writing” drops to just one student—it’s no longer the dominant concern. “Length” persists at three mentions, suggesting some students still struggle with production.

But now four students identify “Using details and elaborating appropriately (neither too much nor too little)” as their problem. This is qualitatively different; it’s not whether to include detail but how to calibrate it for rhetorical effect.

Two students now mention “Doing multiple drafts and using peer, parent feedback.” This represents a shift from solitary production to social revision, from getting it done to getting it right.

Trimester 3 reveals transformation. “Simply doing the writing” has disappeared entirely. “Length” drops to one mention. Instead, the problem space has fundamentally expanded. Seven students—over half our sample—identify “Experimenting with new styles and forms” as a problem they’re working on.

Five mention “Having a desired emotional effect on a reader.” Four describe “Finding satisfaction with how a piece turns out.” Four continue working on elaborating appropriately, and three are using feedback through multiple drafts.

These are writer problems, not student-completing-assignment problems. Students are asking: How do I create the effect I want? What happens if I try this approach instead? Am I satisfied with what I’ve made?

They’ve internalized enough craft knowledge to play with conventions, developed enough aesthetic judgment to evaluate their own work, and gained enough confidence to experiment with risk.

The progression is clear: from procedural survival (Can I do this?) to technical execution (Can I do this well?) to rhetorical sophistication (Can I create the effect I intend?). Students move from teacher-defined problems (meet the length requirement) to writer-defined problems (find the right balance of detail for my purposes). The problems become increasingly complex, nuanced, and self-directed.

Why This System Accommodates AI as a Problem-Solving Tool

This problem-solving portfolio approach from the 1990s offers a robust framework for integrating AI into writing instruction precisely because it focuses on the problems students are solving rather than the tools they’re using to solve them.

Consider how AI intersects with the developmental trajectory visible in our data. Those Trimester 1 problems—“Simply doing the writing,” “Overcoming writer’s block”—are exactly where AI might provide genuine scaffolding without short-circuiting learning.

A student paralyzed by a blank page can use AI to generate a rough draft, then face the more interesting problem of transformation: How do I take this raw material and make it actually say what I mean?

How do I shift it from generic to specific, from adequate to compelling? The problem doesn’t vanish; it evolves from production paralysis to rhetorical revision.

If a student uses AI to overcome writer’s block, the entry slip requires them to articulate that process. What prompt did you use? What did AI generate? What problems emerged that you didn’t anticipate? How did you revise what it produced? What did you learn about your own writing process?

This structured reflection prevents AI from becoming an invisible shortcut and instead makes it a visible tool for problem-solving that students can analyze and refine.

The Trimester 2 problems—elaborating appropriately, working with feedback, revising through multiple drafts—become more pedagogically rich with AI available. Students might ask AI to elaborate on a thin paragraph, then analyze whether those elaborations actually serve their rhetorical purpose.

They could generate three different versions of an introduction and use peer feedback to determine which approach works best.

They might compare AI-generated feedback with teacher and peer responses, noticing patterns and discrepancies.

The problem-solving work intensifies because students have more options to test, more approaches to evaluate, more decisions to make about what works and why.

Crucially, the portfolio assessment structure rewards this kind of investigation. Because examination committees evaluate growth and learning rather than just final products, students can document their experiments with AI as part of their development as writers.

An entry slip might explain: “I wanted to experiment with different organizational structures, so I asked AI to reorganize my argument three ways. I learned that chronological order buries my strongest evidence, but topical order lets me build toward my most compelling point.” This demonstrates sophisticated problem-solving, not dependence on technology.

Those Trimester 3 problems—experimenting with styles and forms, creating emotional effects, finding satisfaction with results—represent exactly the kind of advanced work where AI can expand students’ problem-solving territory.

Want to experiment with writing in the style of different authors? Generate examples, then analyze what makes each voice distinctive and which approach serves your purpose.

Concerned about emotional impact? Test different phrasings with AI, then check those predictions against real reader responses.

Trying to find satisfaction with your work? Use AI to push your revision further than you might have thought possible, then reflect on whether those changes actually improve the piece or dilute your vision.

The portfolio system accommodates AI not by ignoring it or banning it, but by making it part of the problem-solving toolkit students learn to use strategically. The entry slips create accountability for thoughtful use.

The sustained timeline gives students space to experiment and learn from failures. The assessment focus on growth rather than perfection means students can document how their understanding of AI as a writing tool evolves over time.

What our 1990s data show is that students can discern increasingly sophisticated writing problems when given structured opportunities to name, investigate, and reflect on their problem-solving processes.

That developmental trajectory doesn’t disappear with AI—but it does require us to design instructional systems that preserve the problem-solving work while accommodating new tools.

The portfolio approach provides that system. It focuses on problems, not products. It requires reflection, not just production. It assesses growth over time, not just final outcomes. It creates space for experimentation and risk-taking.

These features made it effective for developing writers in the 1990s, and they’re exactly what we need to develop writers who can use AI thoughtfully in 2025 and beyond.

AI will keep evolving, but the needs of developing writers remain strikingly consistent. They need room to struggle with authentic problems—first the basics of getting words on a page, then the craft of shaping ideas for an audience, and finally the artistry of experimenting, persuading, and seeking satisfaction in their work. Portfolios gave students that kind of space in the 1990s, and they still can today.

If we design systems that honor reflection, growth, and experimentation, AI becomes part of the problem-solving terrain, not a threat to it.

The real danger isn’t that students will rely too much on AI, but that we will reduce writing instruction to a checklist and deny them the chance to wrestle with increasingly sophisticated questions about writing.

The future of writing education depends on whether we protect those questions and give students the tools—old and new—to pursue them. That’s the work before us.