Helen’s office on the first floor of the Education Building was filled with shelves of children’s books. Simple curiosities in the moment, the image of this collection resonates all these years later, not simply because they were there, but because of what she said.

I was near the end of six years teaching freshman composition (twelve semesters, 3 units per course, 3-4 sections per term, 30 students per section) and remedial reading (variable units) at community colleges in the Napa Valley. The more sections of reading lab I taught, the more interested I’d become, the more skilled I’d become at reading studies in Reading Research Quarterly (I’d not yet done any work in inferential statistics), and the stronger the urge to study reading grew.

Helen was meeting me to talk about the Reading Specialist program at UC Davis. Information about such programs wasn’t online in 1984, you know. Having subscribed to RRQ since 1980 after working in a private reading clinic as a tutor for two years, I fully expected to fumble around with words I barely knew like standard deviation, median scores, and the like. I thought speaking in these terms would be prerequisite.

Back then during the heyday of quantitativism, all the studies used numbers for evidence to support their hypotheses. I would strategically read the introduction and review of the literature of papers with rapt attention, read the method section to know what the study was about, then cherry pick like a drunken sailor through the analysis of the data, homed in on significant conclusions. The discussion section was buried treasure.

But numbers didn’t come up with Helen. We talked about what brought me to her office with a desire to apply for the reading program, and I was finally able to tell someone how totally fascinated I’d become with reading—just reading, all of it, especially after my experience with kids seriously struggling to learn in commercial reading clinics. As she talked about the requirements, she had a way about her of making them come to life, storytelling what would go on in the courses.

The part about the children’s books on her shelves reaches out to me even today. As she told stories about the clinical experience requirement, tutoring a single child for several weeks, she was thrilled with the fact that I had already tutored literally hundreds of youngsters, that I could bring these experiences to the cohort. Then she said it.

“Schools have always gotten it wrong,” she said, a mixture of sorrow and determination in her expression, an expression I would see again and again in the faces of elementary school teachers with whom I was destined to work.

“When we make shoes, we cut the leather to fit the feet.” She paused, gazing at her books. “When we teach reading, we cut the feet to fit the shoe.”

***

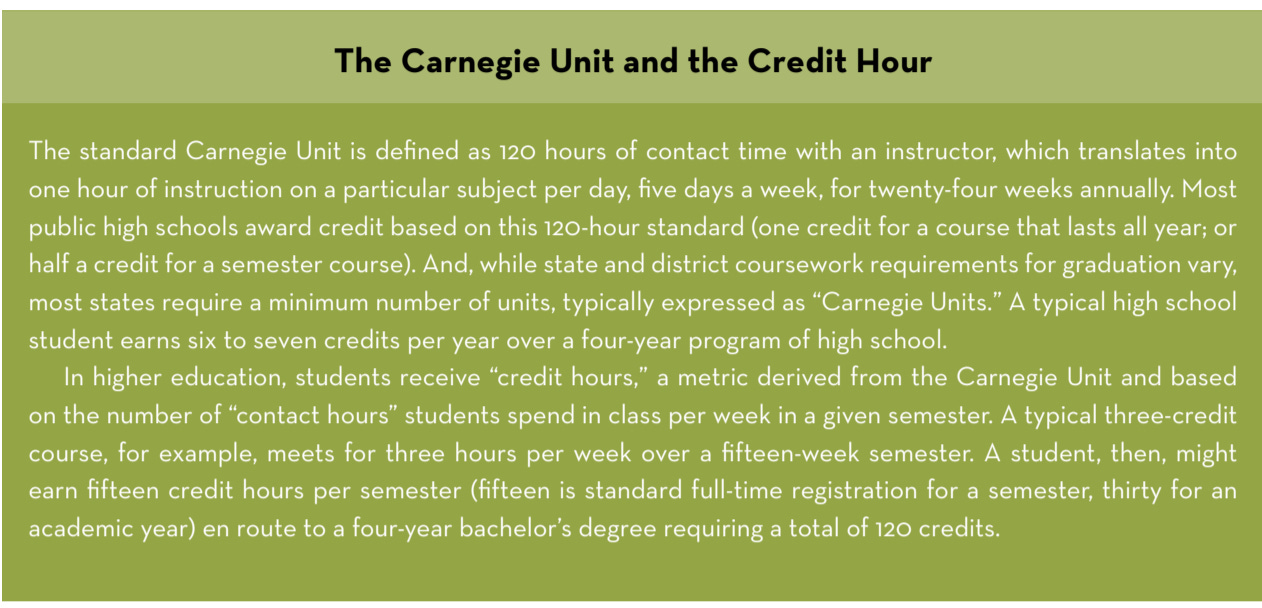

There are no Carnegie units in elementary schools, as near as I can tell. Instead, formal systems of “credit” operate not on units keyed to “hours of work” but on an expected developmental level framework based on the age of learners in “years.” Interestingly, in the United States at least, because units of credit calibrated in “hours” have not been socially constructed to manage instruction for pre-adolescents, most states have devised a tool to authorize curriculum based on units of “minutes.” The unit at elementary and secondary levels remains seat time with a nod toward learning outcomes.

However one slices and dices the curriculum, however, whether hours, minutes, or even seconds as the time-on-task research does, turf wars engaged in by the adults in charge of the system are more informed by interests held by adults than by learners. For example, at the elementary level adults currently are battling for “units of minutes” in the “school day” to be allocated to “science” vs. “reading.” It’s ironic that the same philosophical struggle is playing out internally in the war between “science of reading” and “balanced” reading.

At the secondary level turf battles have resulted from downward pressures. University entrance requirements of the A-F variety in California, for example, shape the nature of the experiences learners have—or do not have—in high school. The contest has largely turned on the problem of remediation, whether students “deficient” in reading, writing and/or math should be “remediated” in high school or become a drag on higher education.

Helen’s insight into the barbarity of cutting feet to fit leather materialized from a figured world, an ingenious method to create order from chaos, into the real world in the early 20th century. In a study published by the Carnegie Foundation, Sylva, Taylor, and Toch (2015) told the origin story as follows:

“At the time, American higher education was a largely ill-defined enterprise with the differences between high school and colleges often unclear. To qualify for participation in the Carnegie pension system, higher education institutions were required to adopt a set of basic standards around courses of instruction, facilities, staffing, and admissions criteria. The Carnegie Unit, also known as the credit hour, became the basic unit of measurement both for determining students’ readiness for college and their progress through an acceptable program of study. Over time, the Carnegie Unit became the building block of modern American education, serving as the foundation for everything from daily school schedules to graduation requirements, faculty workloads, and eligibility for federal financial aid.”

Both complementary and supplementary to one another, the Standardized Achievement Test and the Carnegie Unit worked their way so deeply into the machinery of American public schooling, they have become all but invisible, if not physically a part of society, viscerally so.

In 1906 when Andrew Carnegie wrote a $10,000,000 check to finance a task force to define the meaning of “college,” the impetus was a deeply disturbing black hole in the force and function of either “high school” or “college.” Iowa State College, for example, required students to be fourteen years old, able to read and write in English, and able to pass an arithmetic test. Moreover, as Collins (1977) reported in The Credential Society, only 10% of American young people graduated from high school. It remained for the 21st century to articulate that public school is all about preparing children for “college or career readiness” in the adult world.

Sylva, Taylor, and Toch (2015) expressed the ambivalence the Carnegie Foundation harbors regarding its role as the origin of the Carnegie Unit, which provided an effective way to lift schools, particularly universities, from a disorganized, unequal, amorphous collection of institutions, loosely speaking, to a stable and durable resource serving ever increasing proportions of Americans as the decades passed—roughly another 10% entering college each decade through the 1970s.. In today’s world, the Carnegie Institute is fully aware of its role as an impediment today and is trying to lead the way toward breaking the black box this Unit has become:

“Many change advocates charge that the Carnegie Unit has slowed the pace of…reforms. They argue that by stressing students’ exposure to academic disciplines rather than their mastery of them, the Carnegie Unit discourages educators from examining closely students’ strengths and weaknesses and masks the quality of student learning. And by promoting standardized instructional systems based on consistent amounts of student-teacher contact, it discourages more flexible educational designs” (p.10).

Europe may be ahead of the United States in this effort, at least from a historical perspective. The European Credit Transfer and Accumulation System (ECTS) was developed in 1989. ECTS sought to facilitate recognition of academic qualifications of students studying abroad and to improve student mobility within Europe. A pilot phase involving thirty-two universities across twelve countries fine-tuned the learning outcomes-based method for transferring credits between institutions, and in the 1990s it began to spread across Europe. The Bologna Declaration of 1999 led to the creation of the European Higher Education Area (EHEA) with the objective of cementing the approach institutionally.

In the United States it seems fair to say that a bureaucratic time-on-task unit-driven test-based architecture that has failed to produce equal outcomes across socioeconomic and ethnic groups is ripe for change. Revisiting the warning about remembering the past before designing the future is in order. Currently, education seems to be doubling down on tinkering with the status quo to serve the interests of adults, and the factory model itself remains a hidden downward pull. This, too, shall pass in the fullness of time.