Before utility companies matured enough to produce and transport electricity to human communities, candles made from tallow or beeswax or lamps that burned oils or kerosene lit up spaces at night. After the first central power plant was built in 1882 by Thomas Edison in New York City, the Pearl Street Station, direct current (DC) was supplied to 85 customers in a one square mile area. On September 4, 1882, the electrical age commenced.

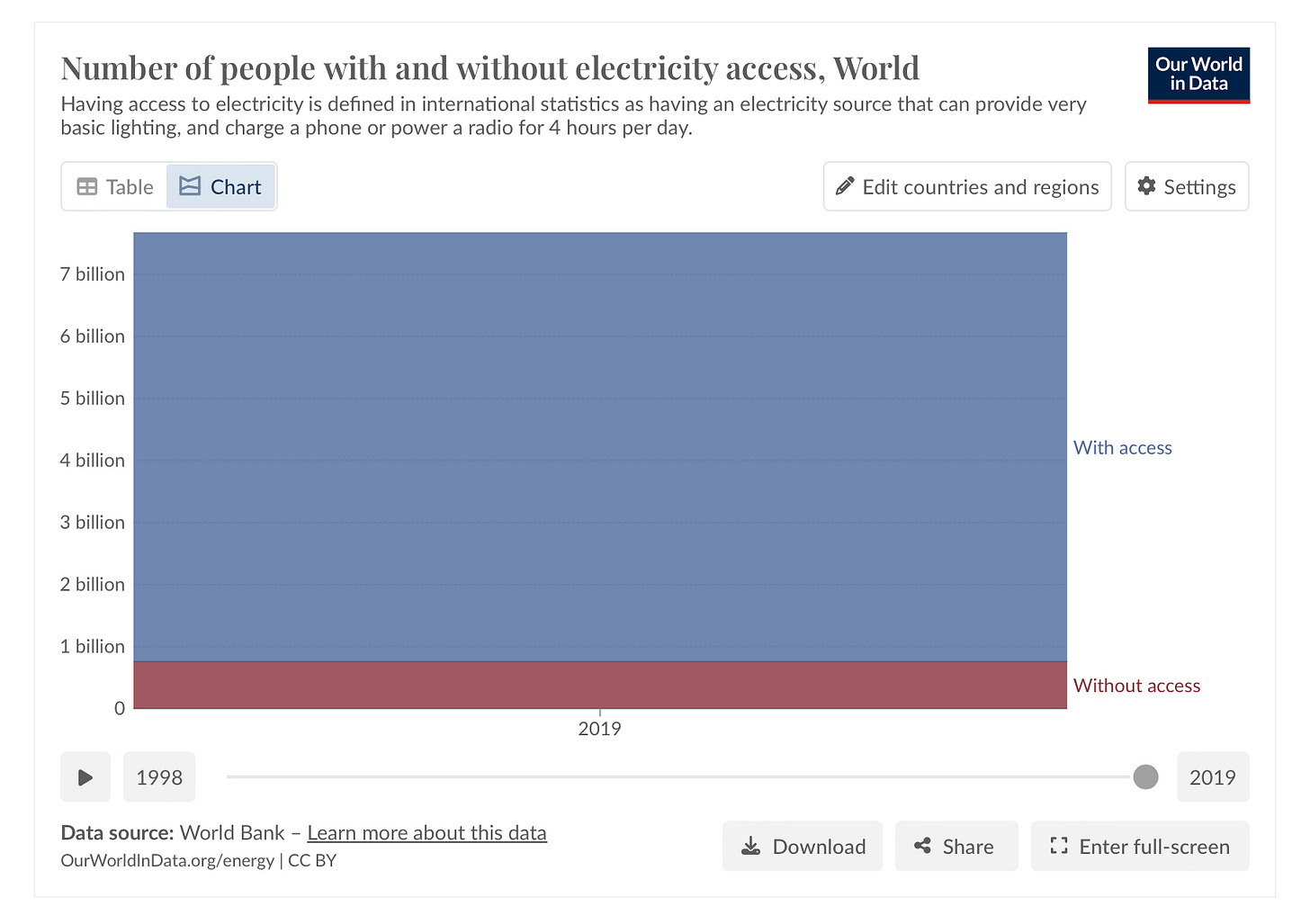

Today, electricity is ubiquitous through much of the world. To grow the business potential from a single power plant in New York to a major source of energy everywhere, George Westinghouse would have to build a power plant in 1886 that made alternating current (AC), a type of current that could be stepped up in amplitude, transported through high-voltage wires long distance, and then stepped down through transformers for local use. Congress had to pass the Rural Electrification Act in 1935, and by 1960 90% of US farms had power. The following chart depicts the availability of electricity across the planet today:

The growth of electricity as a reliable power source provides a nice example of a “black box” in Bruno LaTour’s actor-network theory of sociotechnical innovation. ANT for short, the theory was built from anthropological studies of scientists doing their research in laboratories. In Latour's conception, a black box has known inputs and outputs, but the internal workings are generally opaque and obscured except for their access by a small number of experts. For the electrical system, an input could begin with our intention to turn on a lamp (flipping a switch), and the output would be the light or the appliance functioning in fulfillment of our intent. The network in between is "black boxed."

Active parts in a black box are called “actors.” Actors are either agents or actants in an ANT. Inside this black box is a complex network of both human (agents) and non-human (actants) actors. Agents include power plant workers, engineers, managers, supervisors; actants are regulators, transformers, wires, meters, and even the electrons themselves. All these actors work together in a network or assemblage to produce the final result. The electrical system has become so reliable that we take it for granted. Stability is a key feature of a black box in Latour's theory; relations among agents and actants have become so established they are often thought of as a single unit.

The black box nature of the system becomes apparent when something goes wrong. A power outage, for example, suddenly makes visible the network we normally ignore. Then we do what Latour would call "opening" the black box. Black boxes often have authorized maintenance agents and actants who understand the nodes, assemblages, and pathways inside. For them the box is transparent. Actants in the electrical system teach humans standardized "scripts" for behavior. We know to flip switches, pull chains, plug in devices, and pay our electricity bills without thinking about it. These scripts are part of how the black box maintains its stability.

This ANT box translates the actions of power plant operators and the physical properties of burning fuel or spinning turbines into the convenience of household electricity. The process of translation is a key concept in actor-network theory. For example, teachers use certain algorithms, tools, and tests to translate student learning into letter grades. Like the grading system, the electrical system operates at multiple scales, from the individual household/school to the national grid/university systems. This multi-scalar nature is characteristic of complex socio-technical systems in Latour's theory.

Actor Network Theory (ANT) requires a single or a collective actor to initiate activities inside a black box to produce an outcome. In the case of a lightbulb, a conscious and intentional agent can flip the switch to produce light. Or an actant could flip the switch—an actant is a non-conscious, non-intentional actor like a timer. Just as a mechanical or electrical timer could be an actant in the network, the switch itself is an actant. As such, the switch has no intention and can complete its function and nothing more. In our example, an agent flips the switch. Another node, an actant called a timer, could translate the signal of an agent, giving the network a degree of autonomy and authority. The black box can produce light with indirect human direction.

The actor network theory we will explore in some depth in this article is the grading system in high schools across the US as a tool for determining who graduates and who gets accepted into a university. Within this black box, grades are used for a variety of purposes like eligibility for sports, placement in a more advanced class, etc. We won’t focus on these systems. The question under discussion is this: How do the agents and actants in the grading system function to sort students into five categories of accomplishment—A, B, C, D, or F.

*****

Unlike the electrical system, the output of the grading system black box is significant not for physical, but for symbolic outcomes. The dominant agent at input to the black box is the individual teacher. Actants in the system take a variety of forms. Informal quizzes, formal tests, assignments, projects, and homework serve as methods of data collection. Performance on these assessments is determined largely through mathematical formulas when possible—point values are arbitrarily or systematically assigned to finished tasks with points awarded or deducted based upon teacher judgments of student work.

Issuance of grades as output depends on school policies, which are actants in the black box. School policies on grading can vary significantly between high schools, even within the same district or state. Some schools use a traditional A-F scale while others might use a numerical or percentage-based scale. The cutoff points for each grade can vary (e.g., an A might be 90-100% in one school, but 93-100% in another). Some schools use a 4.0 scale, others a 5.0 scale (especially for weighted GPAs), and the way GPAs are weighted for honors or AP classes can differ.

The importance given to different types of assignments (homework, tests, projects) can vary. For example, some schools might cap homework at a certain percentage of the overall grade. Policies on accepting late work and associated penalties differ widely as do make-up policies in terms of time allowed and potential grade impacts. Some schools allow extra credit while others prohibit it, and the types of extra credit allowed and how much it can impact grades can differ. Some schools allow test or assignment retakes, and some schools offer pass/fail options for certain courses.

How attendance affects grades can differ (e.g., automatic grade reduction for excessive absences. Consequences for cheating or plagiarism and how they affect grades can vary. Policies on modifying grades or grading practices for students with IEPs or 504 plans can differ, and the process for students or parents to appeal a grade can vary between schools.

Agents, human actors involved in the input function of the black box, are primarily teachers, department heads, and principals. Teachers are tasked with designing their individual grading systems sometimes in consultation with colleagues and department chairs, always within the boundaries of administrative policies. Principals are held accountable for ensuring the grading system is implemented according to policy for each grading period. Output of the system is of interest to parents and potentially others interested in understanding how well a student is doing.

Students are recipients of the output of the system, and they do the work that is being graded, but they often have no voice in the work they do and how it is evaluated in the black box. One might argue that students have opportunities to be agents in the grading process in that they are responsible for deciding on the quality of their work they will strive for, but the traditional system provides no actant to capture their self-assessments to report on a transcript or a report card.

The increasing influence of educational technology (e.g., learning management systems, automated grading tools) is an emerging actant in the system. The degree to which qualitative and student self-report data might enter the black box is uncertain, but many teachers lately have communicated deep problems with the current system because the school all but dominates students in terms of learning opportunities and evaluation outcomes. There are serious questions about the dehumanization of learners during a period of rising awareness of the toll of oppression and control of student cognitive activities. The black box reinforces existing power structures in education through assignment and assessment actants and through decontextualized evaluation.

Who does the grading system serve? This question ought to concern all of us. Direct beneficiaries are parents and other adults who might use report card grades to reward or punish young people. Often, parents have little idea of the experiences students have had in the classroom and even less understanding of what they may or may not have learned. The school benefits because grades serve as an easily identifiable product of the physical plant and also help monitor students as pieces on the chessboard of the curriculum.

Bourdieu (1991) in Language and Symbolic Power explicated the ways in which good grades can amplify the value of one learner in the eyes of others while bad grades can diminish the one with low grades. If the goal is to leave no child behind, this situation is at best counterproductive:

“…One can understand the effect of all social…credit and credence—of credential which, like aristocratic titles and academic qualifications, increase in a durable way the value of the bearer by increasing the extent and the intensity of the belief in their value…” (p.119).

Grades, then, reflect not only performances of the past, but influence performances in the future. One question that comes to mind is this: Why do we use the grading black box so often in school? What would happen if grades were issued once a year?

*****

"Even though grading may be at best a dubious value 'educationally,' it is absolutely vital to a culture that puts enormous stress on success, achievement, and individuality and to a system that requires social and economic inequality,” Romanowski (2004) noted in the Kappan.

This quote captures the paradox of grades. They are of dubious value partly because they are self-referential. An A is an A? Devoid of meaning, they represent a subjective judgement relying upon actants like quizzes, tests, homework, and attendance—even rubrics can be highly problematic if they aren’t really good rubrics. Or they represent a number of countable facts or definitions or right answers a student selected or provided to narrow questions or tricky problems. High-quality feedback is a powerful cognitive refresher, but a grade is mute. Grades are deictic references; their meaning is completely contextual. Here we are. No, we’re over there. A little more to the side. The other side.

Even if grades were crystal clear, reliable, and valid, there would still be problems—maybe even worse problems. The “enormous” stress on individual achievement in the context of a cultural requirement of the best and the brightest to be identified and transported to the Ivy League—grades work for affluent learners, not so much for high-poverty or marginalized learners. A skeptic might think the grading system is a tool for placing young people in economic classes, not a way to improve social mobility.

Letter grades are challenging for many teachers, cold, troubling, nagging. It’s hard to take joy in the ranking and sorting of one’s own students, picking winners and losers in the lottery of life. Being fair, being consistent are not just technical difficulties, but moral dilemmas that keep teachers awake at night. Grading is inherently subjective, and teachers take seriously their obligation to every learner to give their students the appropriate denomination (A, B, etc.) based on pre-established and clear criteria.

Given this discussion, I have three recommendations for classroom teachers that do not involve political activism. These recommendations are also subject to grading practices and policies at individual schools or in departments. But I think they can be implemented in varying degrees of intensity. Teachers will need to reduce use of traditional actants, deemphasize the salience of grades in the classroom culture, and try to organize students in collaborative and self-regulated learning agendas and projects.

To repeat, high-quality feedback is a powerful cognitive refresher, but a grade is mute. Teachers could develop and implement a comprehensive feedback system, a black box with predictable inputs, assemblages, and outputs. This system could involve written comments, audio comments, one-on-one conferences, or peer feedback sessions. The goal would be to provide students with meaningful information about their learning progress and areas for improvement, going beyond the limitations of a simple letter grade.

Note that even rubrics can be highly problematic if they aren't really good rubrics. Teachers should invest time in creating detailed, clear, and fair rubrics for assessments based on examples of student work. These rubrics should outline specific criteria for each grade, helping to make the grading process more transparent and potentially more objective. Regularly review and refine these rubrics based on student performance and feedback. The greater the collaboration among learners and colleagues in writing rubrics the better. Personally, my sense is that rubrics for teacher use only written by that teacher in isolation are probably ineffective.

To address the self-referential nature of grades and the moral dilemmas teachers face in "picking winners and losers," teachers can implement regular self-assessment and reflective activities for students. Students could grade their own work using the same rubrics as the teacher, write reflections on their learning progress, and set personal learning goals. This approach can help students understand the grading process better and take more ownership of their learning, potentially reducing the stress and inequality associated with traditional grading.

Reading issues like this is inspirational thanks to the wide approach used to explain things and involve different perspectives. Thank you for sharing!

I used it as part of my Effective Teaching class the last few years, on the recommendation of my son-in-law who went through the STEP program. I think Joe's wife is a lecturer there at Stanford? Anyway, he came to a session we held for the secondary folks and then later I heard him during a Davis school board meeting - they had a pilot study with interested teachers for at least a year looking at some aspects of his recommendations. I really liked the concepts, as they were just well packaged in his book, but were all based on pretty solid research. He's a great personality and can carry his message with teachers!