Lately, I’ve been using a blue pad for handwriting. I couldn’t think worth beans without physical notebooks. I’ve filled composition books galore with grist for the mill, notes, thoughts, reflections, each notebook linked to some major thing that dominated my attention, usually for long spells stretching into years. Pedagogy of the Oppressed consumed 1981 and two steno pads front and back.

Easy come, easy go. I’ve left them in conference hotel rooms, cleared out shelves of old ones to make room for new. After the flood in 1986 that took most of my books and papers, the heartbreak which lingers alas changed my behavior. How could I have stopped trying to protect my notebooks? Books are replaceable. Aging is a no nonsense teacher.

I only wish I could lay my hands on some from the 1980s and 1990s. I made a profound mistake treating them so casually after the flood when I lost so much. Anything on a shelf above my waist survived. The rest, books and papers, floated like so much flotsam and jetsam in muddy river water.

***

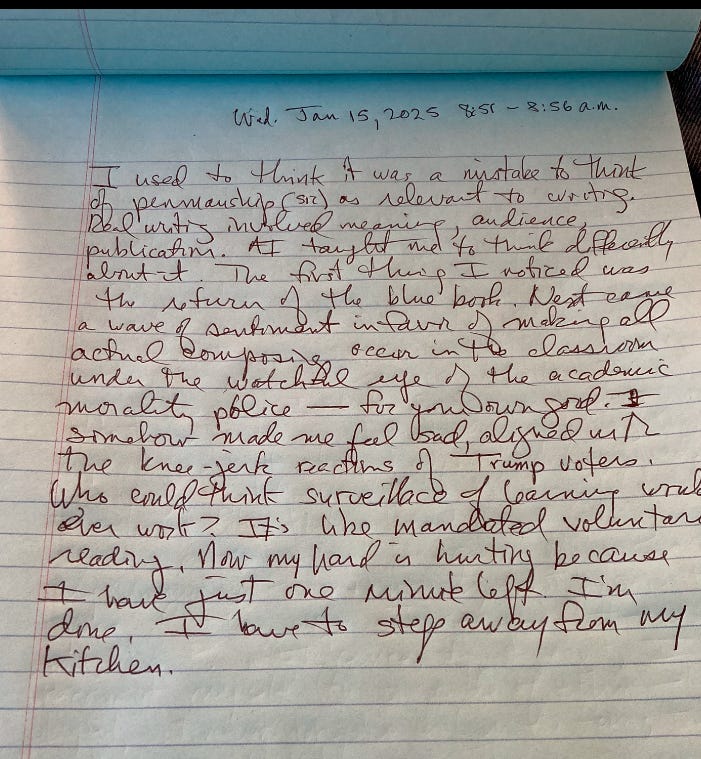

It isn’t in the reading of the text that the spontaneous handwriting of a journal has its mind-bending impact, but in the writing. Several minutes ago, I set myself a task I want to reflect on with you. I’m calling it Fill the Page in Five Minutes:

“You have five minutes. Fill a page in your blue pad with your thoughts in the moment. Try not to think about the fact that this page will be posted on Substack. You don’t have to fill the page, but you have to see that as a goal. You must write legibly. You must not cross anything out. Observe the time limit.”

Under these circumstances I learned something consciously I’ve been on the verge of learning since I learned about the new laws mandating handwriting instruction. In California, Governor Jerry Brown circa 2018 discovered at a campaign stop that a fourth grader couldn’t read his signature. Of course, I thought it was an absurd law—mandating handwriting.

As time passed and I reflected on the importance of handwriting in my own writing process, my perspective changed. I don’t like absurd political intrusions into teachers’ professional prerogatives. So the passage of the law, any such law, disrespects the teaching profession.

But handwriting brings the hand, the wrist, the arm, the eyes, the gestures (my wife laughs at me because I gesture with my left hand as I write with my right, impossible at a keyboard, right)? I think I whisper to myself as well.

Handwriting slows down psycholinguistic processes in two ways. It lurches from word to word, the fillers come quick, the substance stops the moving finger in its tracks. You need a word to move on, a word.

Second, it leaves micro spaces at the end of structural units like phrases and clauses for thinking, bringing a Vygotskian internal urgency for thought to find language before thought dies down. You have to think syntactically because once you start a syntactic unit on paper and you can’t cross out, you are toast.

It’s not that writers don’t stop to think at the keyboard. It’s just too darned easy to get something down and go back to edit. There is too much seductive opportunity to blather and edit and too little advantage in stopping for long. Plunge ahead. It’s easy to change later and it might be ok.

***

When I am stuck during a reading event, AI can often get me unstuck and let me move on (tsk tsk!). It’s not rocket science. Usually, I need a piece of knowledge I missed or don’t have. Such is life.

But when I’m stuck during a writing event, I have to think about it.

My first impulse is to go to my notepad and start to label ideas and see what’s up with the expressing of them. It’s much quicker than a bot oftentimes because I don’t get sucked down a rabbit hole unless it’s my own doing, which I don’t mind at all. Not that the bot is necessarily bad, but the bot has no simulated idea of what’s going on at the moment in my head, and I’m writing to collect my thoughts. I don’t need a diversion.

When I’m writing I need to know what’s going on in my head, not what’s going on in the algorithms of collaborative technology. Now, there are times when a bot can help. Say, I’m writing about Donald Trump’s reading non-habits. A search bot can—and did—deliver a bag of gold to my doorstep, credible essays on everything from his failure to read briefing materials to his preference for one-pagers with bullet points.

Experience is a good teacher.

***

“You have five minutes. Fill a page in your blue pad with your thoughts in the moment. Try not to think about the fact that this page will be posted on Substack. You don’t have to fill the page, but you have to see that as a goal. You must write legibly. You must not cross anything out. Observe the time limit.”

I asked Claude to respond to this text. I uploaded this jpg. It’s amazing that the bot can read handwriting but can’t handwrite, at least as far as I know. I could ask Claude but his training is archaic, having a cutoff of 2023. I have my hypothesis on this front.

Bots unwittingly serve up responses that can crack me up they are so clueless. “There’s something happening here but you don’t know what it is, do you, Mr. Jones” (Bob Dylan, The Ballad of the Thin Man). Here’s a good example:

This appears to be a handwritten journal entry dated January 15, 2025, where the writer reflects on their evolving thoughts about penmanship in academic writing. They describe having previously dismissed penmanship's relevance, but then experiencing what they call a "blue period" followed by a "wave of sentiment" regarding classroom composition practices under academic oversight.

The writing has an introspective, slightly frustrated tone, especially when discussing what they perceive as institutional control over writing practices. The entry ends on a personal note about physical discomfort from writing and needing to step away from their kitchen.

The handwriting itself is in a flowing cursive style, though it appears to have been written somewhat hurriedly on lined paper. The text demonstrates exactly the kind of penmanship that the writer is contemplating in their reflection.

What interests me about this piece is how it connects personal physical experience (the hurting hand) with broader academic and institutional questions about writing methods and oversight. Would you like to share your thoughts on how handwriting relates to academic writing in today's increasingly digital world?