Fani Willis, the attorney prosecuting the conspiracy indictment against a ragtag band of ‘leaders’ and a few midlevel agents who attempted to corrupt the popular vote count in Georgia in the last Presidential election, is under a crescendo of media scrutiny today regarding the upcoming hearing on Thursday exploring her fitness to serve in that role. She is between the horns of a binary future; she could be deemed fully fit or unqualified.

The former President has a decision to make. Two court sessions are being held on Thursday. Which shall he attend? In one, he would have the pleasure of spectating at the grilling of his nemesis on a hot spit, attending a funeral marking the death of a fearless soldier of justice. But he could also feel the pain of losing, being dissed, the hollowness only the darkest power monger can experience. Either way, he wins. He’s a big strong hero or he’s a persecuted angel.

Or he could go to the hush money trial, where instead the indictment asserting he used campaign finances and fraudulent accounting to pay for Stormy Daniels to keep her big mouth shut is happening. Of course, he had a different take on what she could do with her mouth back in the day. From Duck’s point of view, he’s got two bitches attacking him for being the Duck. He’s got to turn it around, make a mole hill out of a mountain. Unfortunately, to succeed in uncovering the maneuvers of a worm, one must get down in the dirt with the creature.

*****

This constellation of discursive formations in the courts and in the media provide an opportunity to apply Norman Fairclough’s (Language and Power, 1989) notion of intertextuality central to the discipline of critical discourse analysis (CDA). Grounded in Bakhtin’s notions of heteroglossia and dialogicality, two topics I’ve discussed previously (let me know if you want more info) Fairclough took a pragmatic approach and separated speaking and writing, recognizing fundamental differences in affordances between real (spontaneous in vivo) vs. composed discursive space.

He recognized the existence of writing-intended-to-be-spoken and speaking-intended-to-be-written, though he focused on the written text and its constructive and destructive forces. One special interest was “…the speech of another introduced into the author’s discourse in concealed form [emphasis in original]” (p. 303). His explorations in intertextuality and masked voices ranging from advertising to journalism to the novel encompassed intertextual links both horizontally in present time and vertically in history.

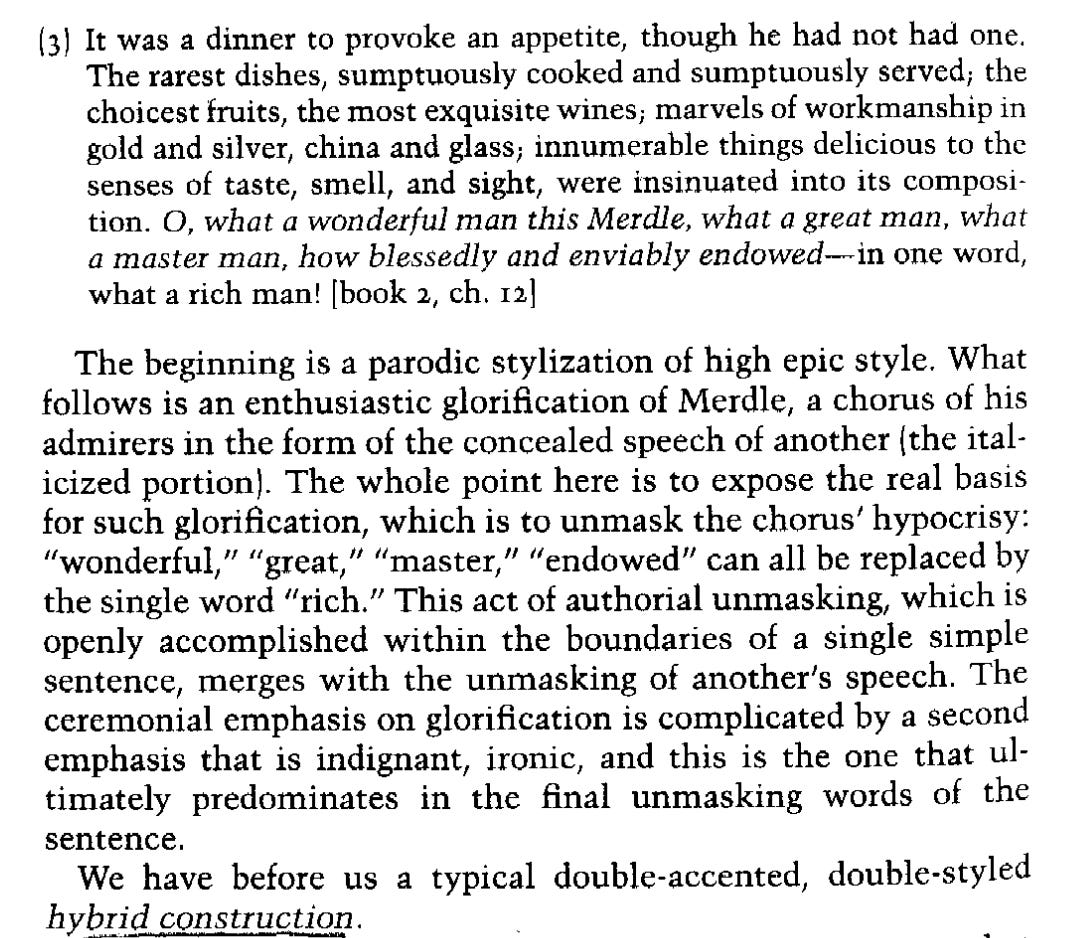

For example, Fairclough selected Dicken’s novel Little Dorrit published serially between 1855-1857 to illustrate horizontal intertextual connections occurring within past history. Rapid industrialization in the Victorian period widened the gap between wealth and poverty much like the conservative ideology of our current generation has done. Dickens' father had been imprisoned for debt in the Marshalsea Prison, a circumstance at the heart of his portrayal of the prison in the novel. Little Dorrit was born and grew up in the Marshalsea. Dickens' moral outrage around inequities and corruption shifted his intuitive intertextuality composing tools into hyperdrive. The character Mr. Merdle is a distasteful idiot representing the financial scandals of the time, particularly the collapse of the Royal British Bank in 1856. Merdle commits suicide when his fortunes fail him.

The following screenshot taken from chapter four of Fairclough’s 1989 book shows how Fairclough approached this complexity of intertextuality:

Anyone who has read Homer’s Iliad, the poetic epic siege of Troy, recognizes the listing of the choicest foods and finest wines that go on page after page, the celebrations for superhumans like Achilles and military geniuses like Odysseus. Why do we, the Chorus, glorify men of this ilk, men like Donald Trump, like Merdle? Because he is worthy of such bounties! O, spiritual Orb! Ironically, this is also the basis for excoriating him as a moral leper who should be in the prison himself.

****

The Trump hearings themselves could be analyzed vertically and horizontally for intertextual links and incorporations of the texts of masked voices, for ventriloquists throwing their voices masked as an attorney or a politician or a voter; any number of dissertations will be done using methods of critical discourse analysis to grasp the textual devices that metastasized into a full-blown societal and constitutional crisis.

These hearings, like those chains Jacob Marley bore for his sins, this hurricane of hearings hurtling against the public’s short, grumpy, weakening attention span, is “breaking news” on CNN. On Twin Earth, FOX is churning out its editorial reporting, gleefully lapping up stagnant water in a pond of misfit misanthropes. Let me end this essay with a brief analysis of intertextuality in the throats of anchors on CNN bringing the news and interviewing the newsmakers.

*****

As I watch the screen the CNN head is displayed as a head and torso on the screen. It happens to be a white man wearing a navy blue suit and tie with a pink shirt, a uniform for male anchors institutionally. Don Lemon got fired in part for his gaudy attire, recall. He discusses the scuttlebutt about which hearing Trump will attend and then cuts to a reporter who cuts to an informant in a dizzying cascade of ventriloquation and intertextual incorporation. Underneath the mystery—which hearing will Trump attend?—left unspoken, are the discursive strategies Donald Trump has forged to hybridize court hearings as campaign events. Trump needs a cast of predictable voices to throw his voice from his throat to the ears of the Deplorables, now a fossilized troop akin to the Copperheads of the Civil War era.

By speaking his lines from a teleprompter, the talking head double-voices two conflicting authors. One authorial voice, the production managers under a boss at CNN, puts words in the head’s mouth on pain of punishment if they are not spoken—the head could be fired. The head may well realize that by giving voice to these words, by speaking about Trump’s hearing attendance dilemma as though it is worthy of attention, he is wasting the audience’s time on a trivial matter. He does a nice acting job of generating excitement, almost creating an advertisement enhancing the significance of the matter.

The second voice is a chorus of Trump’s legal and campaign managers, expecting journalists to ramp up suspense: O, what is the man who was sent by God to save us going to do? Will he attend Burger King or MacDonalds? We know that the talking head is aware he is taking action with words precisely as Trump wants him to. He says as much without saying so directly. He tries to hide his own voice enough to avoid setting off the alarm for the CNN brass, who insist on “fair” coverage, while imperfectly camouflaging his awareness of Trump’s troublesome, sly enlistment of the media in his bid to stay out of prison.

After briefly describing the hush money hearing, a thorn in Trump’s side for years now, the head turns the focus to Fani Willis and Georgia and the effort to remove her from the case. Why might this hearing be “worth it” for Trump to attend? Did he ever have any intention to attend it? What does it matter which trial he attends? Why does the head repeat the gory details of the case against the attorney? Why no repetition of the gory details around Stormy Daniel’s? Silence can be textualized as an element of discourse. I’d be especially interested in your take on who you unmask as the speaker of the words “boot from the case.” Those words sound like cousins of “two bitches,” “whackos,” Trump’s own salty monikers. Who told the head to say “boot” as in “You’re fired!!!” Any moral outrage? The head speaks: