If you suspect that the Knowledge Matters Campaign (see my previous post for a review) has a hidden agenda, you’re in good company. Any slogan with the word “knowledge” in it is enough to raise the hackles of poets, who sometimes suspect the purity of integrated history-literature courses. Poetry Matters, Too, we want to add. E.D. Hirsch, an English professor who talked about “core knowledge” and “cultural literacy” in the 1990s, stirred a hornet’s nest by saying things like “Teachers should be the sage on the stage, not the guide on the side.”

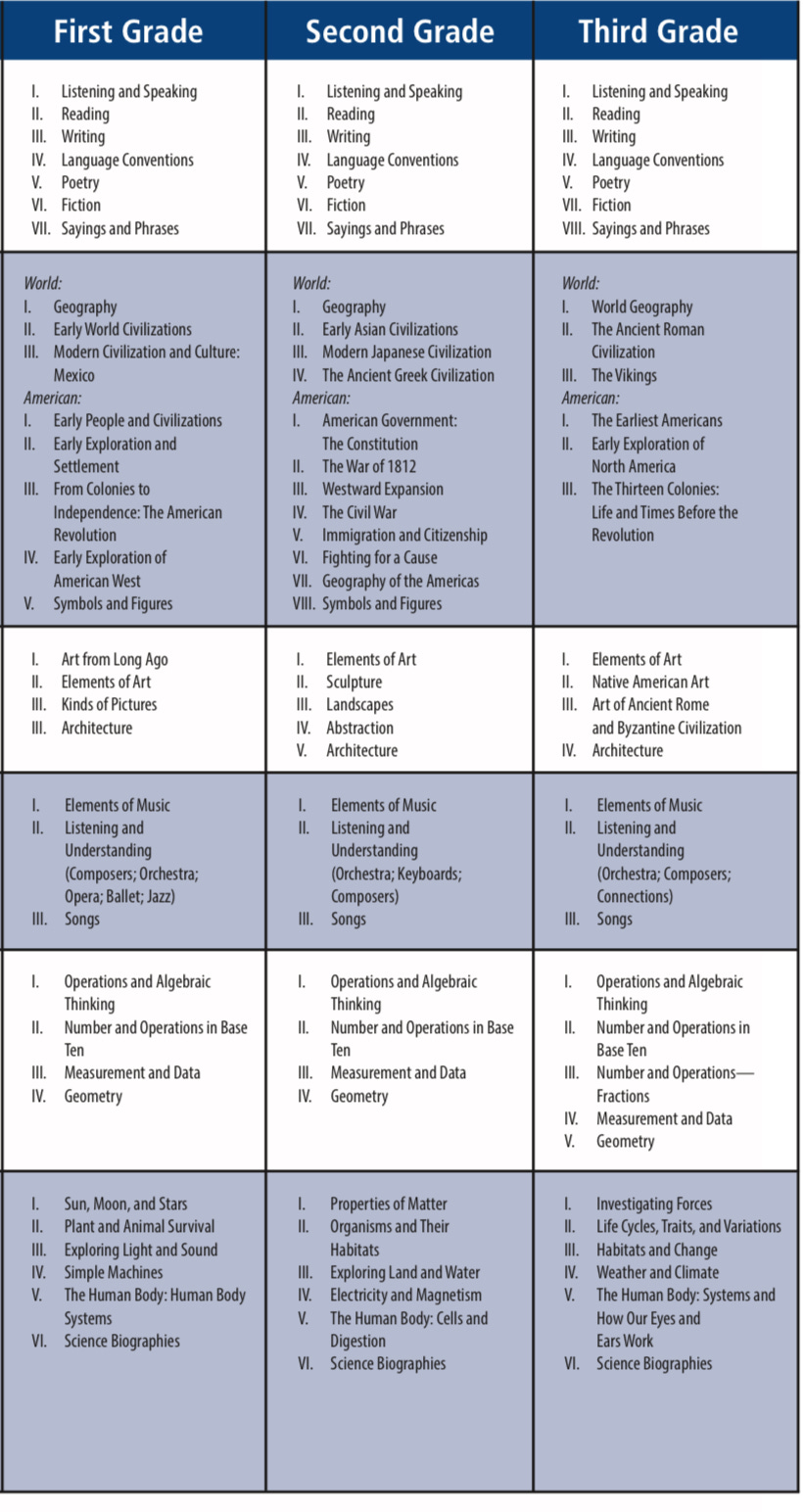

Hirsch, in fact, has spawned a core knowledge movement with cultural and linguistic machinery mass producing a know-it-all curriculum with a grassroots appeal. Home schoolers in particular embrace the logic and materials for sale at the Core Knowledge website. Here is a screenshot of the knowledge curriculum prescribed on the site:

Notice that this chart spans an entire school curriculum soup to nuts. Specific topics are identified specifically so that every students will gain knowledge about every topic every day of every school year—sort of a stretch version of the 18 months it took to train the first natural language bots. The Knowledge Matters Campaign (KMC), a very different tool, in contrast, is a self-described “plugin,” not a curriculum at all, ready to support local curriculums as they are enacted in neighborhood schools. Moreover, the focus of KMC is on the process of knowledge building, not on specific content outcomes. KMC does not specify, for example, that second grade should cover the War of 1812 (check the Core Knowledge graphic above).

E.D. Hirsch Jr., an influential American educator and academic literary critic, was a professor of English and education at the University of Virginia for almost 40 years. Hirsch's seminal work, Cultural Literacy: What Every American Needs to Know, was published in 1987 and argued that a core knowledge base is required of every American to function competently in society. It isn’t coincidental that the term “core” showed up in the label we apply to our national standards for students. This core knowledge—covering a wide range of topics from history and literature to science and social studies—was considered key to effective communication, critical thinking, and civic engagement (hence, college and career readiness).

It was and is easy to miss the complexity of Hirsch’s idea, especially since he worked so hard to write a dictionary of core terms every knowledgeable American must know to compete intellectually. Of course, scholars were outraged—who does this guy think he is? That would have been me, I freely admit. But thoughtful scholars of the time were not so quick to dismiss him. McLeod (1990) writing in the journal Rhetoric Review (Vol. 8, No. 2) made a point that resonates in this moment generally about the conflict among reading scientists:

“We may feel that Hirsch and others like him ignore the notion of education as an active process, of learning how to learn: of not only accumulating but searching for and creating knowledge through research, through experimentation, through writing. We should not, however, ignore Hirsch's research findings, whatever we might think of his conclusions (emphasis added)” (p.273).

It’s disheartening to see the insight that could have prevented the War of the Phonemians officially declared by NCLB so clearly articulated in 1990! We should never ignore valid and reliable research findings, we should always separate findings from conclusions, and we should resist non sequiturs. Hirsch found that shared knowledge is a necessary element in the discourse of competent citizens. That is a finding. But he concluded that the way to create competent citizens is to package those bits of knowledge in a scope and sequence chart and drill/test the populace. Sound familiar? As near as I can see, the Knowledge Matters Campaign has taken the core finding from Hirsch and a raft of other researchers while setting aside his conclusion.

*****

As an English teacher, Hirsch emphasized the idea that reading comprehension requires not only language proficiency but also a broad understanding of shared knowledge, cultural references, and allusions. Hirsch's critics argued that it enforced a hegemonic Eurocentric curriculum. Once again, the non sequitur comes into play. On one hand, it’s obvious that readers can’t deeply understand texts unless they know references and allusions knitted into the text. Still, do we help readers develop the content knowledge we know is distributed inequitably among the citizenry by lecturing to them or forcing them to read under threat of failure and then testing them in a standardized manner?

What happens to the funds of knowledge and the cultural capital students from otherwhere bring to the classroom? Directly teaching the knowledge base of the elite reinforces existing hierarchies and privileges. How does a knowledge-based curriculum centered around convergent thinking not reduce schooling to rote learning when the hoped for outcome upon graduation is to produce people who think critically, creatively, and confidently?

In many ways, the Common Core standards for the English Language Arts were created to address these underlying paradoxes by ignoring them. Where Hirsch viewed knowledge as information in need of transmission, the teacher the sage on the stage, the Common Core architects steered clear of any discussion of instruction. Here is what students need to know and do. We will help with testing, we will help the textbook publishers, but you, teachers, you have to figure out how to teach it.

*****

The Knowledge Matters Campaign does not offer the mother of all scope and sequence chart of topics to be “covered.” The first sentences in the KMC tool dispel any notion of topic prescriptions. Importantly, the KMC architects returned to the initial impulse driving Hirsch, i.e., supporting instruction in reading comprehension. There is no high-falutin’ intent to equalize the population by inoculation across the entire educational enterprise—just a mild pragmatic reminder that schools are, after all, in the business of knowledge, and reading comprehension is a dominating factor in success. The fact that schooling may become a better tool in a democracy perfecting itself rather than a stronger screen letting some in, keeping some out, goes unsaid:

“This tool is for use by states, districts, and schools when examining an English language arts/literacy (ELA) curriculum to determine the degree to which it is ‘knowledge-building.’ The tool is designed to be used as a plug-in for other evaluation instruments and rubrics, many of which mention knowledge-building but none of which have effectively illuminated in detail how this is accomplished in ELA curricula. We hope publishers will use this tool to guide improvements in their products as well.”

KMC is not intended to be applied in every discipline. The second set of sentences in the tool make clear that science teachers teach science, history teachers teach history, etc., but the reading and writing students who are taking instruction in those disciplines require prior content-specific knowledge developed over preceding years of schooling. It falls to the English-Language Arts teachers to teach reading comprehension of both fiction and nonfiction, a project dependent on both cognitive skills and strategies and content knowledge:

“Building knowledge through content-rich ELA curricula should never be considered a substitute for strong history, social studies, and science instruction in the elementary grades. And, in the presence of high-quality curriculum and instruction in these disciplines, which will include opportunities to use and practice one’s literacy skills, we can imagine that time dedicated to English language arts might be brought back in-line with other disciplines.”

In a pure Core Knowledge curriculum which would prescribe content coverage for every day of every grade level in a nightmare of a factory model school, the standards themselves would dictate the goals of instruction, serving as instructional blueprint: “Second Grade Objective 2.1—90% of students will identify 80% of the attributes of Athens as an organized city-state.” Using the tools and philosophy of the Knowledge Matters Campaign, local professionals would be responsible for collaborating on creating and revising local knowledge maps with threshold concepts made relevant to the learners living and breathing in classroom:

“Curriculum is designed to seamlessly integrate practices from ELA standards in reading, writing, speaking, and listening, as well as facility with language. The standards themselves are not the goal of daily instruction; instead, the goal of instruction is to develop students’ ability to understand texts they encounter and to express that understanding in multiple ways. Standards mastery is the end result of, not the organizing force for, reading instruction.”

Michael Smith and George Hillocks (The English Journal, Oct. 1987) like McLeod (1990) found in Hirsch a highly useful insight for English Education. Similarly, they separated Hirsch’s research findings from his conclusions. After discussing the current status of English Language Arts instruction at the dawn of the Whole Language era, they quote Hirsch in an excerpt I’m not sure I would associate with the schema for “cultural literacy” I made for myself over the years. I’m learning. Witness from Hirsch:

“The new picture that is emerging from language research is more completed and more useful. It brings to the fore the highly active mind of the reader, who is now discovered to be not only a decoder of what is written down but also a supplier of much essential information that is not written down. The reader's mind is constantly inferring meanings that are not directly stated by the words of a text but are nonetheless part of its essential content. The explicit meanings of a piece of writing are the tip of an iceberg of meaning; the larger part lies below the surface of the text and is composed of the reader's own relevant knowledge. (E.D. Hirsch, 1987)”

.