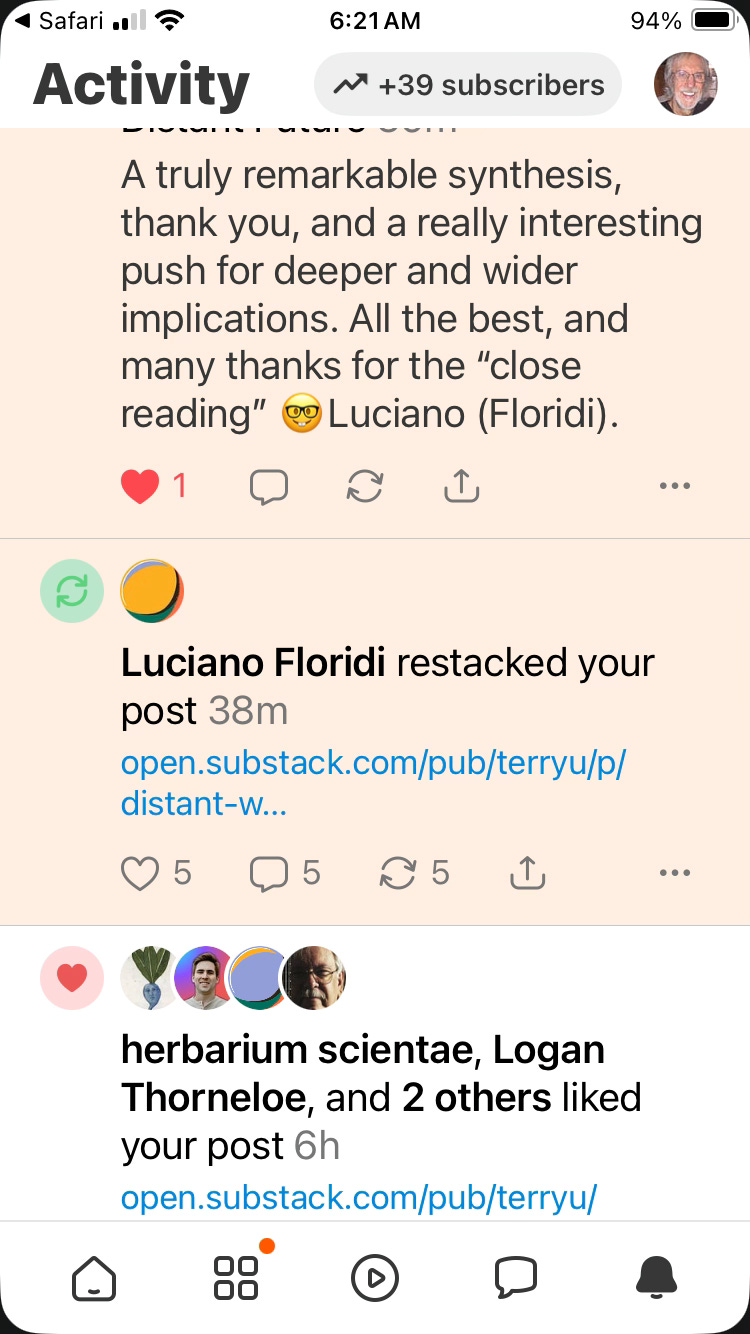

I’m happy to report that I got an A+ on my post of May 15 about Floridi’s concept of “distant writing” for those of you who read it. If you haven’t, I think you will understand this post just fine. I woke up the next morning and found this delightful comment. Talk about a boost of confidence:

Floridi's "Distant Writing" (2025) discusses an approach to literary creation where human authors function as designers while Large Language Models (LLMs) perform the actual writing. This "distant writing" positions the human not as the holder of the quill but as the envisioner, the all seeing I, the agent with intelligence. As Floridi explains, "Unlike traditional authorship, distant writing... positions the author not as the direct textual producer, but as the architect of narrative possibilities [emphasis added], responsible for specifying requirements, affordances, and constraints, and curating the LLM-generated content."

Floridi’s (2025) article rewards a methodical critical reading followed by imaginative extension. In examining the same article today, I'll employ a targeted approach in this post: 1) explicate three consecutive sentences from a key passage where Luciano distinguishes between machine outputs and human writing; 2) for each sentence, I'll offer my interpretation; 3) following each interpretation, I’ll offer implications I see for how we conceptualize and teach writing in an AI era.

Part 1: Three Important Sentences for Writing Teachers

Sentence 1: Stylistic Signature

“A significant observation from experiments in distant writing is the emergence of what might be termed an 'LLM stylistic signature': identifiable patterns, rhythms, and structures that characterise texts generated by specific models regardless of the stylistic parameters established in prompts."

Floridi begins this sentence cautiously, using the words "might be termed" to acknowledge the polysemous nature of 'style' as a core value of writing, an umbrella term which crystallizes ineffable aspects of literary texts. This linguistic hedging reflects his recognition that extending traditional literary terminology to machine-generated text requires careful qualification. He recognizes that mechanical outputs need naming but resists fully embracing "stylistic signature,” a phrase that imports human-centered assumptions into a non-human process.

The core observation, that LLMs produce consistent linguistic patterns regardless of prompting, establishes the phenomenon requiring conceptualization while signaling that conventional literary terminology carries misleading semantic baggage. The tentative language here serves a precise philosophical purpose. By framing this as something that "might be termed," Floridi acknowledges he's entering contested terminological territory.

He's identified a pattern requiring language, but our existing vocabulary is laden with humanistic assumptions about intentionality, consciousness, and expression. This sentence does important philosophical work by naming a phenomenon while simultaneously questioning whether our existing terminology can adequately capture it.

Sentence 2: Dataprint

"Regardless of quality, and independently of the specific stylistic choices (e.g., emulating Austen) determined by the human designer, LLMs exhibit common patterns—such as rhythm, narrative structure, distinct ways of initiating, developing, and concluding a story, lexical preferences—forming an identifiable literary pattern that can be termed their dataprint."

Here Floridi introduces an intriguing neologism (as far as I know) "dataprint,” an almost forensic rather than artistic term. This choice separates machine patterns from human "stylistic choices" with an unmistakable force. Unlike "style," which carries axiological weight and implies intentional expression, "dataprint" suggests mechanical traces devoid of expressive intent. The components he identifies (i.e., rhythm, structure, lexical preferences) are described factually no attribution of artistic or emotional qualities to them. A train has rhythm, playground equipment has structure, lexical preferences sound like settings in a university library journal search. They are identifiable patterns rather than meaningful expressions, reinforcing their mechanical nature.

This sentence performs important conceptual work by establishing a relationship between what the human designer intends ("stylistic choices") and what consistently emerges despite those intentions (the LLM's "dataprint"). The enumeration of specific elements that constitute a dataprint (rhythm, narrative structure, etc.) helps readers understand precisely what aspects of natural writing carry machine traces. The juxtaposition of "human designer" with "LLM" reinforces the fundamental division of labor in distant writing. We have conscious intention on one side, refined and calibrated statistical pattern reproduction on the other.

Sentence 3: Voice

"Clearly, the term 'voice', often used to describe human authors, would constitute an inappropriate anthropomorphism (Floridi and Nobre 2024), but it is close in meaning, as it refers to the distinctive and consistent style, tone, and perspective expressed throughout a writer's works, making their writing recognisably unique."

Floridi's reference to "perspective" here is crucial. AI lacks agentic perspective because perspective requires a fixed position from which to observe and interpret the world. Humans develop perspective through embodied experience, accumulated memories, and a distinct, mobile location in physical, social, and historical space. AI has none of these constitutional elements. Any seeming "perspective" in AI output must be assigned or simulated. It is never a given.

This sentence establishes both similarity and critical difference. By acknowledging that dataprint is "close in meaning" to voice, Floridi prevents readers from dismissing the comparison entirely. Yet by explicitly labeling "voice" an "inappropriate anthropomorphism," he establishes a crucial boundary. The reference to external work (Floridi and Nobre 2024) signals that this isn't merely a terminological preference but connects to a broader philosophical argument about anthropomorphizing AI. Most significantly, the emphasis on "expressed throughout" implies intention and consistency that mechanical processes cannot possess.

Summary and Application: Signature, Dataprint, Voice

Floridi suggests a specific term to integrate what we mean by “signature style” and “voice.” Dataprints have distinctive syntactic patterns and lexical choices that emerge in the textual interstices of AI-generated output. He argues that using the term "voice" for AI would constitute an inappropriate anthropomorphism, since "voice" in human writing encompasses both deliberate stylistic choices and characteristic personal elements.

Dataprint allows us to discuss AI's distinctive textual characteristics without implying consciousness or intention. “This section reads a little like a dataprint paste,” a teacher might say. “This section using the word ‘dwell.’ I’ve personally not dwelled on much of anything for too long.” Or “Let me see if you can help me understand this section,” another teacher might say. “It has too many of those hollow words we often see in dataprint. It leaves me unsatisfied. Is there another way you can explain it so it has more meaning for me?”

Another might hold a conference with a writer and point out features of the text that reveal what human readers value in terms of style and voice. “The words you use to describe what you saw when we visited the Art Institute are strong, helping me step inside the experience you are describing.” In another section the teacher might comment “Here we’re beginning to see that voice disappear. It’s sounding like dataprint. It’s sounds like how AI might describe the Art Institute, you know, like dataprint.”

Different AI models develop recognizable dataprints. For example, Floridi notes that the GPT-series tends to be "more lyrical, expansive, and introspective" while the Claude-series is typically "more direct, lean, and pragmatic." These patterns emerge from the models' training data, architectures, and generation processes, rather than from any conscious stylistic intent. This distinction is important for Floridi's broader argument about how we should understand AI-generated literature and the changing nature of authorship in the age of large language models.outputs and human writing.

Part 2: Reclaiming Writing as a Human Enterprise

Floridi's careful distinctions between dataprint and voice arrive at a critical juncture in our cultural understanding of writing. For millennia, writing has served as the cornerstone of human knowledge transmission, identity formation, and cultural continuity. It has been our primary technology for extending thought beyond the boundaries of individual minds and across generations. What we've always implicitly understood—that writing is fundamentally a human activity imbued with intention, perspective, and lived experience—AI has forced us to articulate explicitly.

This is precisely why Floridi's terminology matters so profoundly. By naming the "LLM stylistic signature" as "dataprint" rather than "style" or "voice," he isn't engaging in semantic wordplay. He's establishing conceptual boundaries that preserve writing as a meaningful human enterprise, conceptual boundaries we need to make sure we teach. Without these distinctions, we risk collapsing crucial differences between statistical pattern reproduction and genuine human expression.

The consequences of this terminological confusion extend far beyond academic debates. When students, educators, and society at large fail to distinguish between dataprint and voice, we fundamentally misunderstand both human and machine capabilities. We evaluate human writing against inappropriate standards of machine-like correctness and consistency. We attribute intention and meaning where none exists. Most dangerously, we begin to view our own expressive capacities as a less efficient version of what machines can produce.

What's required now is not endless philosophical hand-wringing about whether AI can "really" write, nor breathless techno-utopianism about AI's creative potential. What's needed is precisely what Floridi provides: clear-eyed, pragmatic terminology that allows us to work with these tools while maintaining essential distinctions bookended by non-negotiable ethical principles. The concept of dataprint gives us language to discuss bot-generated text for exactly what it is—the predictable output of statistical processes—rather than fetishizing it as something more mystical or meaningful—or diabolical.

Our educational systems must anchor themselves in this understanding. Writing instruction should explicitly distinguish between the mechanical regularities of machine output and the intentional expressivity that characterizes human communication. Students need to recognize dataprint as forensic evidence of computational processes, not as expressions of creativity or perspective unless birthed by legitimate, highly skilled, human “distant writers.” This recognition doesn't diminish AI's utility; rather, it properly contextualizes it.

The stability of our cultural understandings around writing isn't academic. Writing has always been how we preserve cultural memory, how we negotiate shared meanings, how we extend our thinking beyond individual lifespans—how we make social structures like governing Constitutions. To surrender these understandings to technological confusion is to risk severing connections to our own history and to each other. Floridi's work invites us to move beyond both AI panic and AI worship toward a more grounded approach: recognizing patterns for patterns, tools for tools, and preserving the irreplaceable human dimensions of written expression as precisely that—human.

It's time to get down to brass tacks. AI text generators are powerful tools that produce recognizable dataprints. Human writers are embodied, intentional beings who develop authentic voices. Both have value, but they are not the same. Our future depends on maintaining this distinction with unwavering clarity.

I like the term dataprints, like the marks a chainsae leaves on a cut log.

Excellent news!