Reading Instruction in General Education: Transformation through Self-Authorship and Strategic Literacy

Why do students in the United States have to take two years of General Education while students in Europe face no such requirements? This question still boggles the collective European mind. In 2008 and 2009 I attended quite a number of conference presentations in the United States focused on Europe’s Bologna Process wherein higher education across the ocean was undergoing the “tuning process,” i.e., getting university faculty singing from the same songbook in terms of expected learning outcomes.

Presenters spent considerable time on questions like “what is a learning outcome” and “how do we know when one has been accomplished”? Bloom’s Taxonomy, especially the significance of verbs like “analyze” and “evaluate,” was enjoying a mini renaissance. The key to a learning outcome is its verb, not its adjectives. American assessment coordinators like me, faculty often from communication studies, sociology, or education, had trouble understanding how a university could function without General Education. Is it possible to achieve higher-order learning behaviors without depth and breadth of knowledge?

As the tuning process hummed along seeking harmony in universities with deep roots in the old world, our own American Association of Colleges and Universities (AAC&U) was engaged in writing rubrics for fifteen higher ed, higher order learning outcomes, assuming that learners would spend as much time developing cross-cutting, universal habits of mind in GE as they spent developing specialized knowledge in a major.

One presenter clarified this mystery for me in a non-scientific but plausible way. She referenced Angela Merkel who had addressed the question informally in a talk the presenter had heard. In 1999 when the Bologna Process was launched, Merkel had been the German Minister of Education and Research and an active proponent of standardizing and thereby validating the worth of a college degree from any accredited European institution.

According to this presenter, when Merkel was asked to weigh in, Merkel pointed out that the United States has no high culture readily available to the commoners. The United States needs General Education almost as a remediation strategy because it admits students to university who have not been properly prepared. Merkel talked about her own young adulthood and the accessibility of theater, opera, museums, libraries—and why requiring college students, who are ineligible for college in Europe without vigorous secondary school experience, to take courses in the humanities would be redundant. If these assumptions were true, I reasoned, just as lower education is a reflection of the values and political underpinnings of the nation-state, so is higher education.

Like all educational innovations, silver bullets at the origin, over time problems with the tuning approach surfaced. The following quote is taken from the European University Association (EUA). Almost a quarter century after Merkel and colleagues imagined the good that could come from tuning, it seems that not much has changed. Like a rubber band stretched into a novel shape and then snapped back into position, in 2022 the university system in Europe and as near as I can tell in the United States retains the structure which history and culture forged before the tuning began:

A disaster like COVID should never go to waste. If it nudges educators toward reimagining assessment as an integral part of learning, not simply measurements taking place after learning is finished, perhaps it will have a sliver of a silver lining. Of course, superficial learning and self-regulatory purposes for formative assessment can distort the implementation.

*****

William G. Perry was a psychologist and professor in the Harvard Graduate School of Education who conducted a 15 year study of the intellectual and cognitive development of Harvard undergraduates, a study that has received mixed reviews over time because Perry researched exclusively white Harvard males applying an inconsistent and idiosyncratic qualitative methodology. Although Perry’s selection of subjects was obviously flawed, his findings provoked and continue to provoke both discomfort and hope in higher education. This website provides a deep dive into Perry for the interested.

Perry’s stages of development begin with dualism. High school graduates in general believe in received knowledge. Everything is already known, handed down from on high, all problems can be solved, authorities already know the right answers, and the job of the learner is to find them. Sound familiar? Very soon, the college student learns that not all authorities agree, so some teachers must be right and others wrong. So the learner’s job is to figure out which teacher knows the right answers and ignore the others (except on tests).

Stage Two, multiplicity, can last throughout the undergraduate curriculum for some students whose learning posture becomes stable and durable. Knowledge is subjective, not passed down from the gods, a crushing insight with metaphysical and quasi-religious implications. Not everything is known, some problems cannot be solved, in fact most of them are wicked problems, and it doesn’t really matter which answer one chooses so long as the test gets passed. Everyone has a right to an opinion; just be sure it matches what the teacher is looking for. The job of the learner is to pick the answers the teacher prefers and to be able to shoot the breeze using words the teacher likes to hear. (In my dissertation on portfolio assessment, I used an in vivo code for a discourse pattern called “mumbo jumbo.”)

Stage Three is relativism. During this stage learners begin to grasp intuitively the concept of epistemology, though they may have no conscious understanding. They understand, for example, that biologists approach the study of human beings using methods that differ from anthropologists or sociologists. They understand that a poem can be read with empathy and emotion but can also be evaluated using scholarly criteria. Solutions are relative but must be discerned and supported in a context. Whether these solutions square with their own experiences and background knowledge is immaterial.

Stage Four is commitment/constructed knowledge. Learners make a commitment to themselves to examine knowledge learned from others in light of their own experiences and prior understandings. They become more comfortable with ambiguity. They glimpse the bankruptcy for themselves and for others in views of accomplishment as knowing the right answer to questions on Jeopardy. The uncertainty of knowledge, the pragmatics of existence, the proper role of science as an ongoing principled collaborative search for knowledge and its evaluation is humbling and brings about a sense of interdependence and responsibility.

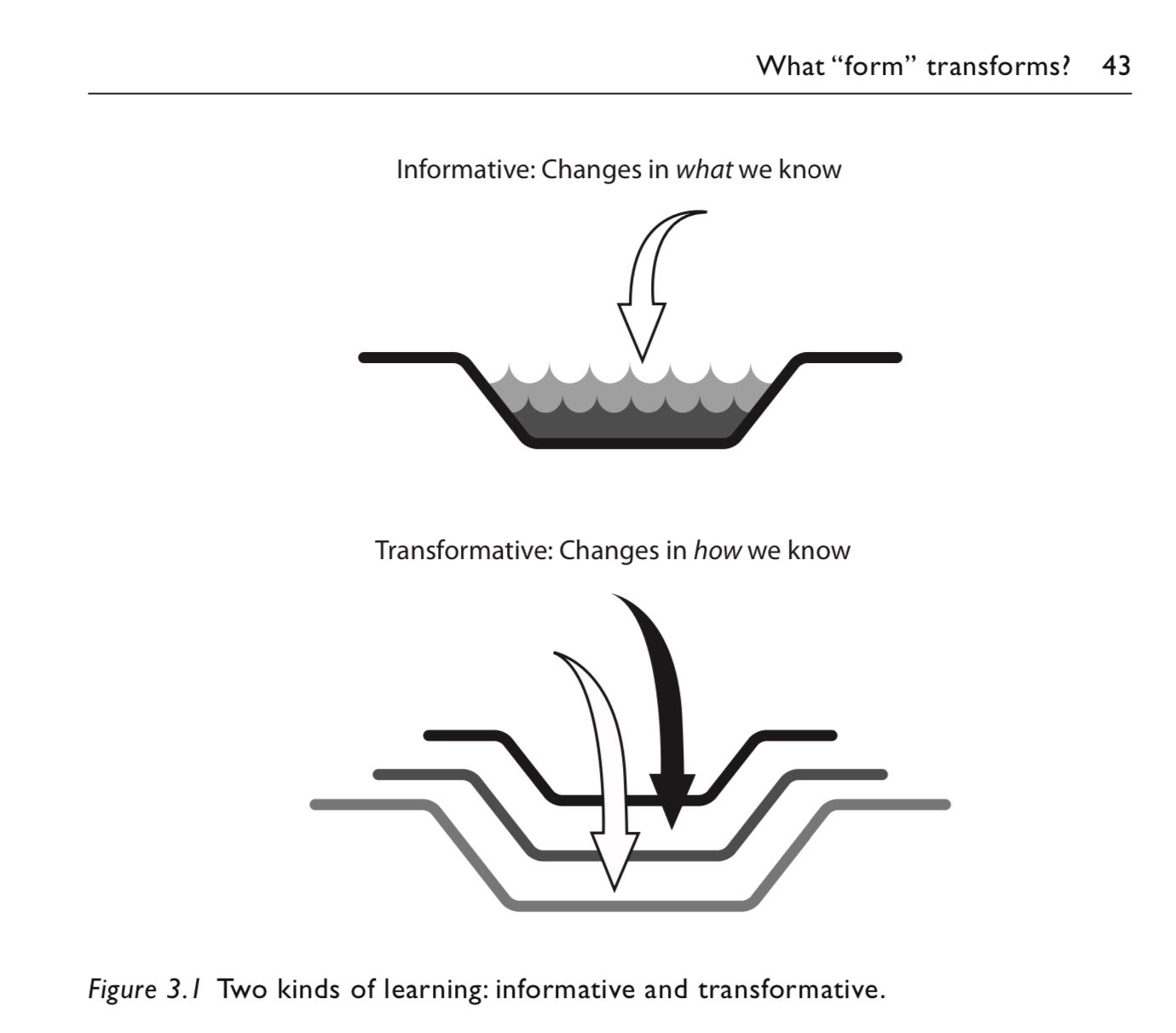

Robert Kegan, another Harvard psychologist and professor following in Perry’s footsteps, challenged the conventional wisdom—the simple view of learning—that adult development as thinkers and knowers is a matter of acquiring more skills and more knowledge. Kegan maintained that information does not define the highly educated being; in his framework reaching the highest levels on Perry’s terms requires transformation. Adults seeking to reach their highest potential as sentient beings develop the capacity to “self-author,” that is, to compose their consciousness intentionally according to self-knowledge. They understand what they do well, they work hard to refine their capacities, they pursue questions of significance to them over long periods, often over a lifetime, and they are committed to their own growth.

The relationship between information and transformation for Kegan is central to his framework. Received wisdom construes acquiring information as the goal of learning, the task teachers face we often see as disseminating information, and research in pedagogy often studies the best ways to transmit information so that students recall it. The following diagram excerpted from a chapter Kegan wrote in Illeris (Contemporary Theories of Learning, 2009) depicts this relationship:

*****

Essential to self-authorship and becoming an engaged epistemologist building background knowledge and expertise deliberately with text, the habit of reflection can be developed. The seminar as an academic space in the curriculum is ideal for reading instruction designed to foster reflective analysis. Jeff’s seminar is particularly well suited because of the variety and complexity of texts assigned.

Because reading is a pillar of Jeff’s seminar, students have rich opportunities to reflect on their processes, motivations, and strategies. Learning occurs in predictable cycles of experience, deepened and strengthened through the prism of hindsight, but it takes time to learn to see backwards—and documenting experiences is helpful.

So I’ve been playing around with a self-assessment tool, a formative tool, Jeffrey might use as a springboard for his own early assessment to infuse metacognitive discussions and reflective analysis into the seminar. My problem with what I have here (draft below) is twofold.

First, given pressures from the culture and historical development of the university to prioritize acquisition of information, time to devote to reflective analysis is scarce in most classrooms. This draft may be too much for an in class assignment. It takes time just to walk through these questions with students to check for common understanding. Is it too much for a homework assignment? Second, are these questions suitable? I’m trying to walk the fine line between providing students an opportunities to self-assess as a first step toward the self- authoring intent of the seminar and Jeff’s need for actionable data. It may be that a knowledge inventory would be useful—e.g., what did you learn about Mesopotamia in 9th grade World History?

It’s interesting that the bot was of no use at all in drafting this early offering to Jeff for his consideration. His vision for the course is paramount, his intuition about intertextual matters invaluable. Any feedback or comments from you are welcome. No, the bot was not helpful—nor did it apologize when it created a list of half baked items reaching back to the days of SQ3R. If the bot is an indicator of unconscious bias, as a people we have some superficial views on reading, what sort of behavior it is, and its role in our inner lives. Reading for pleasure is somehow divorced from reading for serious purposes. I decided to use the heading “casual reading,” but I don’t like the term one bit. Help me if you can. Remember we all live in a yellow submarine.

*****

Name:

Date:

Course #:

Major or Interests:

Respond to each prompt informally, but remember that this information is part of a formal self-assessment which you’ll complete at the end of the course. The information is confidential, subject to self-disclosure. I may invite you to share, but it is your right to decline. The prompts are designed to evoke accurate information about you as a reader to help me better understand you and to help shape the contours of the assignments, which are of course malleable.

Casual Reading

Using the following scale, indicate your characterization of your habits regarding reading for pleasure outside of class assignments. Then briefly comment on your assessment.

1-2: I’ve never been one to read for pleasure

3-4: I’ve gone through periods of reading for pleasure

5-6: I’ve always enjoyed reading for pleasure

In what ways can you be considered a “lost” reader with no agenda? In what ways a “found” reader with an agenda?

Do you enjoy talking with others about what you’re reading? In what settings?

Academic Reading Experiences and Strategies

What strategies do you use to “size up” a reading assignment to be sure that you have time to complete it successfully? How effectively have these strategies worked for you?

What strategies do you use to organize and integrate information and ideas while you are in the midst of reading complex literary texts?

What extra-textual resources do you draw upon before, during, or after reading an assignment online or elsewhere, including conversational AI?

What motivates you to bring your best effort to a reading assignment? What mutes your motivation to exert genuine and interested effort?

What do you do when you are struggling to comprehend the information?

Confidence, Independence, and Interdependence as an Academic Reader

Based on what you know about this course or courses like it you’ve already taken, how confident are you that you can read the assignments in a highly motivated and effective posture? Elaborate with details.

The reading assignments invite you to develop your unique interpretation of each assigned passage. For the culminating experience of the course you’ll integrate these interpretations into your written personal statement of a philosophy of the ancient world and significant ways you see that the ancient world shapes the modern world. What strategies will you use to complete these individual assignments while organizing yourself to write this paper?

Interdependence is an assumption of this course. Meaningful participation in discussions inside and outside class, including online environments, is expected and even required to get credit. Describe experiences you have had participating in class discussions. What characterizes a good discussion for you?

We will have periodic comprehension quizzes to help me assess your growing ability to read the type of texts left to us from ancient and medieval times. How confident are you in your ability to apply yourself and to improve as a close and careful reader of old texts?

Writing about Reading

Describe experiences you’ve had in previous classroom settings using reading logs or journals for the dual purpose of deeper learning and personal accountability.

The signature assignment for this course is a 2,500 word formal essay that expresses your own personal philosophy you created during the seminar. Describe any previous experiences from middle school, high school, or college that prepared you for this project.