Reading Comprehension in a Piagetian Framework:

What to Do When Reading Assignments Fail to Produce Authentic Learning

Authenticity

Piaget integrated the theme of authenticity throughout his theory of learning and development. Authentic learning results from motivated thinking through the relationship between knowledge existing before an interaction or experience and new information perceived during the event on one’s own. Authentic learning can be factually wrong or an inadequate map of reality, but it is real and therefore substantive.

Inauthentic learning often results once language develops through external meddling in internal cognition under the banner of instruction. Pseudo knowledge is received in prefabricated packages recalled in privileged words or phrases. The motivation to integrate and organize new content with prior knowledge through thought is replaced by rote memory of language.

Instruction premised on directing learners to recall words or phrases from memory or to recognize them in print in order to describe a decontextualized set of facts (say, the causes of the Civil War) permits learners to compromise and accept troubling or contradictory ideas without trying to resolve them, to ignore perceived gaps or points of confusion or potentially false assumptions, to construct knowledge that sits uneasily or unclearly in their minds but nonetheless is safe under the flag of a sanctioned word. The temporary pseudoconcept is shallow, brittle, lasting long enough for the test.

Reducing evidence of knowledge to recall of words or phrases on a test weakens learners’ self-confidence and encourages fragmentation, closing off analysis and reflection on deeper structural relationships among concepts, events, settings, and ideas in interconnecting networks of self-tested knowledge.

Authentic knowledge networks constructed through integration and differentiation of schemas at differing levels of abstraction, which Piaget might call scientific knowledge, are obstructed developmentally as long as pseudoconcepts linger, held in place by memorized words, generating surface and unexamined connections with other distorted concepts.

Instruction can’t hasten development of authentic knowledge through coercion. Learners need to think at their own pace and follow their own paths to coherence. Pseudoconcepts are the product of external pressure to learn before appropriate prior cognitive knowledge structures have been interrogated, integrated, and differentiated in light of new information.

Yet instruction can provoke authentic development of knowledge using comprehended text when instruction aims to support learners in thinking on their own. Prior knowledge structures can be activated and unpacked, explored, evaluated in relation to previews of new knowledge before reading. Similarities and differences between set knowledge and new data can be strategically monitored and managed during reading through strategies modeled by a teacher. Analysis, evaluation, and extension of freshly constructed knowledge can be done formally and strategically.

Constructivism as a theoretical perspective on reading comprehension flows smoothly from Piaget’s constructivist theory of learning and development, even though Piaget, according to his colleagues, studied mathematical thinking, not reading. Constructivist learning theory applies to learning during interactions with the physical and social environment. Constructivist reading comprehension theory applies to learning during interactions with texts.

Language

Vygotsky’s perspective on the role of language as a master psychological tool in constructivism required to learn to think is at odds with Piaget’s view that language is merely a conduit for the transmission of information to fuel (or potentially distort) cognitive structuring work. For Vygotsky, language transfers thought from society to the individual and mediates knowledge construction. For Piaget, thought precedes language by two years and is developed during the sensorimotor period beginning in infancy in the absence of language.

Vygotsky concluded that language mediates thinking and knowledge construction. Through acquiring and using language with its non-negotiable sharing of reality among individuals, humans in Vygotsky’s version of early childhood discover the utility of private speech (Vygotskian regulatory self-talk of the very young child which Piaget called ‘babble’ or ‘musical accompaniment’ to thought) and later mature inner speech (syntactically truncated Vygotskian ghost speech-to-self off in the distance that hovers in consciousness to regulate and guide thought). This inner voice shapes the development of thinking from a lower to higher plane of productive work. Outer voices can merge with this inner voice during acts of learning, shaping not just the learning of content, but the thinking that yields learning.

Piaget saw no special role for language as a mediator of thought. At two-years old Piaget found evidence of “semiotic juncture,” that is, the child transitioning from sensorimotor to preoperational thinking discovers the ability to use mental images as symbols for objects. This new ability is profound because it affords the child processes to think about an object not present, to project mentally into the past and the future. Note that these mental symbols are not linguistic. Semiotic juncture marks the emergence of the capacity to transform images grounded in sensory experience, primarily visual, into mental slides which later are labeled and categorized as nouns, verbs, etc. Higher-order thinking and the authentic learning it produces occur with language as a labeling system and a tool for transmission.

I’ve found this discrepancy between two opposing but critically important thinkers useful. On one hand, Piaget makes clear the absurdity of mistaking the behavior of recall of words and phrases as evidence of the existence of carefully constructed, personalized, and organized knowledge. Language does not produce knowledge; thought does.

On the other, Vygotsky illuminates the dual role of language as transmitter and as a regulator and contributor to knowledge production through scaffolding brought in from the social surround in the zone of proximal development. Once language emerges, it can both transmit and shape knowledge,

Motivation and Early Reading

Like other notables in the pantheon of the greats, like Albert Einstein who is said to have died in bed with pen and paper in hand working on a solution to a problem that had plagued him since childhood, like Leonardo Da Vinci who is said to have returned to the Mona Lisa to perfect the image over the final 30 years of his life, like Walt Whitman who revisited and enlarged and republished Leaves of Grass from the 1850s to the 1880s, Piaget continued his research and writing until his death in 1980 at 85. His prodigious output continues to shape child psychology, learning sciences, and scientific pedagogy in profound ways.

Several researchers who worked and published with Piaget over decades in Geneva to extend his research agenda continued to collaborate with him during his later years of life as Piaget worked to perfect and elaborate his theory of development. These colleagues were often asked what Piaget would say about the proper age of onset for reading instruction. The only answer, of course, is that Piaget didn’t have time to study everything.

The assumption beneath this question seems to me to be layered as 1) reading emerges as an add on to emerging language, 2) language emerges as an organizer for a mental library of images and schemas and as a line of transmission, 3) reading instruction is a technical matter providing access to the code.

Explaining how and when children best learn to use the graphophonic system has no anchor in physical and empirical reality, Piaget’s territory of interest. Letter-sound sequences are psychological and arbitrary in nature. Potato or apple, cat or squirrel, these decisions about physical reality are categorically different from decisions about the psychological meaning of long vowels or short vowels. Logically, however, if decoding requires access to an organized system of knowledge, this knowledge must be reinvented and constructed alone in the mind of the child like any other knowledge—when the child is motivated.

Motivation and Reading Comprehension

Reading science theorists have found evidence that comprehension must be voluntary and motivated in that readers need an authentic objective to drive working with, on, and through a text. Passive intake of textual information produces what Piaget would call pseudo concepts. In the absence of a learning goal, readers have limited awareness of the need for integration and differentiation of textual information within and across schemas relevant to the topic. Perhaps the strongest generic drive in schooling is simply to recall words and phrases.

The impulse toward assimilation or accommodation; the drive to confront and resolve problems with text structure, sense, language, organization, implications; the desire for flexible use of cognitive strategies for stepping out of a text for consolidation—these productive behaviors can be provoked and activated through employing evidence-based pedagogy.

In both math and reading if cognitive heat from the furnace of a problem or conflict isn’t created by the learner’s own learning metabolism, new learning can’t be artfully shaped to fit like puzzle pieces within prior learning. Take state capitals. A reader may “learn” the names and location of state capitals in the United States by rote under penalty for failure to recall, but fail to comprehend any meaning. That other countries have provinces with capitals, that capitals are geographical locations of political power, such notions are left unremarked, and learners do not construct abstract general knowledge structures leading to a field of knowledge like “government” or “republic” or “Civil War.”

Teachers can make state capitals problems to solve rather than words to memorize. Sort the capitals by age. What themes appear in the ten earliest capitals in contrast to the ten most recent? Sort the capitals by architectural features of government building across time. Sort them according to the historical existence of a slave trade in the state. What differences and similarities are observable in the statuary?

The work of integration and differentiation to enrich old schemas and make new ones is private, even uncomfortable, disequilibrating. Being told a preferred solution or answer, as in direct instruction, does not produce durable and deep learning that spreads and interconnects schemas. Cognition is cut short by immediate feedback or explanation before assimilation or accommodation can even begin.

Reinvention

The notion of reinvention is shared by Piagetian learning theory and the Science of Reading’s view of comprehension. Piaget’s entire project screams that teachers do not provoke knowledge construction simply by depositing uniform knowledge structures transported through language into the minds of learners, structures of equal value, appearance, and substance across all readers. A knowledge structure already invented in the minds of elders must be reinvented in every single newcomer mind, always nuanced, linked to a unique collection of schemas at multiple levels of abstraction and complexity.

When a knowledge structure like “the US Civil War” is an object of instruction, the significance of learners having prior understanding of schemas like “states” and “state capitals,” “constitutional government,” and the like, becomes clear. The Civil War is a historical narrative documented in primary sources and revealed in cultural artifacts with defining consequences for today. For an adolescent taking US History accustomed to “learning” as recalling the names and locations of state capitals, deep comprehension of the Civil War may not even register as a purpose for reading. Recalling sanctioned words and phrases as specified in the textbook substitutes for real learning about the topic.

Ginsberg and Opper (1988), who published a book on Piaget that serves as my primary source for the information in this post, commented on the human necessity of reinvention:

“Concluding on his own” stands in opposition to “recalling the right answer” and occurs only through constructive reinvention.

Provoking Reading Comprehension

During experiences with the environment where disequilibrium occurs, that is, when the learner senses a tension or a contradiction between pieces of information or simply an onslaught of new information, cognitive subsystems kick in to integrate or differentiate incoming data and organize them, sometimes even remodeling or creating new schemas.

A schema is a knowledge structure, a set of attributes that helps the child identify an object or an event in the environment. There is an intension and an extension associated with each schema, according to Piaget. For example, the intension of an apple scheme involves its shape, color, texture, size, taste, etc. The extension is the apple in the real world. Early scheme intensions are incomplete and idiosyncratic; when confronted with a potato, the child may distort or ignore the source of the conflict and call it an apple. Eventually, with experience, sorting out conflicts becomes more practiced, the central nervous system and sensory equipment mature, and the child learns to move around and expand the experiential field.

The developmental process of an individual cognitive system made up of integrated and differentiated subsystems with tested and revised schemas, according to Piaget, seeks a coherence termed equilibrium. Schema theory as a foundation for current models of reading comprehension, consistent with Piagetian theory, sees reading comprehension as a constructive capacity also seeking coherence and equilibrium but of a unified perspective on a topic..

Unlike apples, which are naturally occurring objects that have color, shape, etc., texts are unnatural, culturally produced, designed to be negotiated cognitively in specified ways according to formal and informal genres. Content-area reading pedagogy consists of lesson design principles and frameworks within and across disciplines that help specify what can be done to provoke comprehension in the service of knowledge production based on interactions with texts.

It’s crucial to note that interacting with a text is very different from interacting with people or things during events in the real world. For example, how often in the real world do you come across a boldfaced word?

“What do you think a boldface word means to passive readers negotiating meaning in a textworld?” I used to ask my credential students routinely. Of course, teachers see boldface as an indicator of importance. “For many adolescent readers it means ‘skip this word,’“ I’d suggest to them. “It means if it’s on the test the teacher will tell you all about it.” This mismatch between the instructional intention to provoke thought and the practical effects in a transmission model is just a sample of the learning problems that turn up when a constructivist process is taken up as transmission.

In my own teaching of content area reading over many years, I’ve used metaphors that I picked up along the way to make the familiar strange, to provoke disequilibrium among my students, all secondary school credential candidates, to assist them in reinventing the schema ‘text’ to serve them as a master schema maturing over decades.

A text as a mirror. How does that work? What would that mean in biology? in a newspaper article? in a novel? Is it possible to see yourself in a text? Is it possible to see anything other than yourself? I asked my students to do thought experiments with carefully chosen passages.

A text as an invitation. Any sense there? Can a teacher invite a particular stance or posture toward a text? How does this metaphor position the reader in relation to a text? What expectations arise for the reading event?

A text as a painting or photograph. In what ways do cognitive approaches to focus and close inspection when viewing a Van Gogh or a an Ansel Adams align with those enacted during viewing a text? Can a text be viewed?

A text as a blueprint. The notion of blueprint as a guide for skilled craftspeople to build standardized houses, for readers to follow the blueprint in order to create knowledge structures identical across individuals, the idea of textbooks being written by committees with boldfaced power sanctioned by political entities led to another metaphor, reading by remote control, Bakhtinian ventriloquation.

Textbooks assigned mindlessly and superficially as transmission device is a dangerous practice. Because texts are multifaceted cultural artifacts produced and reproduced with designs to generate particular kinds of readings, it’s perilous for teachers to approach them as if they were as innocent as apples on a table or a cat in the backyard.

It was also useful to discuss metaphors for a reader with prospective teachers. If texts are cultural artifacts, readers must be cultural agents. The reader can be viewed as a pitcher in a baseball game. Seeing readers as offensive players with the power to influence the overall flow of the game—a different role from umpire or catcher or first base—suggests the importance of features like rules of the game, fairness, moving through innings, equipment, strategies, knowledge of other individuals in the game, the big picture of the World Series.

A favorite of students came from an early edition of Vacca and Vacca’s classic content area reading course textbook: The reader as a cab driver in a busy city. Such a reader needs a working knowledge of likely traffic conditions at a given time of day. Special circumstances like one-way streets, detours, and automobile accidents must be negotiated. Alternate routes to the same destination offer solutions when revisions are required. Checking in with dispatch and keeping up on incoming requests for rides must be weighed against current location and passenger destinations. Experience and reflective analysis as a consequence of lived history on the streets produce learning that multiplies into overall development.

A final metaphorical excursion was about the teacher. The teacher as orchestra leader, all learners using the same sheet music on different instruments with unique sounds and contributions to the overall performance. The teacher as a supervisor or corrections officer or hotel manager. I’ve assigned the writing of a poem on this topic in earlier years to tap into the emotions that drive teachers to want to do this work.

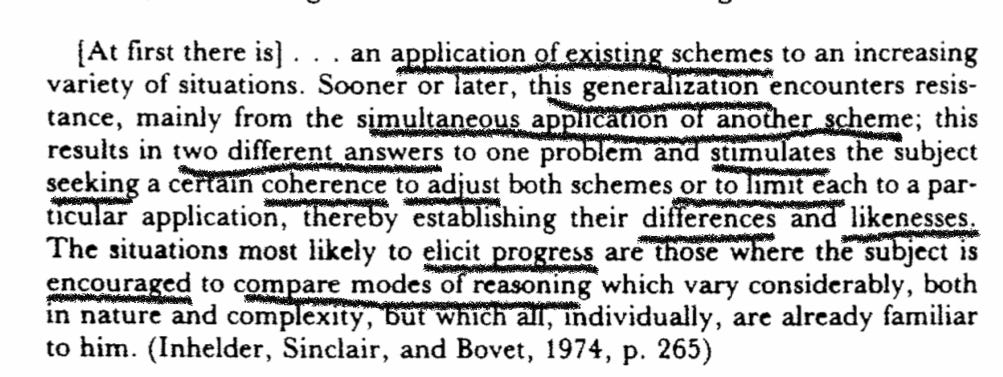

I offer the following quote from Higgins and Opper (1988) as a way to summarize the important links between Piagetian theory and reading comprehension:

In a nutshell, setting up reading assignments to support students’ using prior knowledge to comprehend text through strategies of assimilation and accommodation in a variety of pedagogical situations designed to provoke reinvention and reflective analysis can motivate the reader, who seeks coherence once motivated, to adjust prior knowledge or to make new knowledge. Social situations which elicit progress in comprehension using texts as input encourage readers to compare modes of reasoning (metacognitive conversations) and higher-order modes of negotiating ever more refined and abstract meanings, which are already familiar on a simpler level. When reading assignments fail to produce authentic learning, look to how you design learner provisions for integration and differentiation of new information with prior knowledge before, during, and after reading activities.

NOTE: This post relies heavily upon this book, particularly chapter six. The book is available to download as a pdf at the following url:

https://www.spc4erp.com/uploads/about-1471606029-piagets-theory-of-intellectual-development.pdf