When we talk about financial literacy, we rarely discuss the financial power of literacy itself. In America today, your ability to deeply understand a text might be worth more than your college degree. While politicians debate minimum wages and tax brackets, a silent economic force has been at work for generations: those who can truly read, truly earn.

The financial consequences of literacy proficiency and its impact on knowledge and human improvement work are real and measurable, creating a "green literacy" effect where the ability to interrogate and fully understand texts on a human level directly translates into earning potential. This so-called “literacy wage premium” represents one of the most longstanding, significant economic divides in American society with roots deep in its political history.

This literacy divide reflects broader patterns in American education. Children of affluent families typically experience rich, literature-based education emphasizing critical thinking, interpretation, and engagement with complex texts—the foundations of humanities education. Meanwhile, students in under-resourced schools often receive skills-focused instruction emphasizing phonics drills and standardized test preparation, not to mention five-paragraph essays later on.

The irony is striking: leaders in finance, technology, and politics—those who shape educational policy—generally benefited from humanities-rich education themselves, having attended schools that prioritized literature, philosophy, and critical discourse. Yet the educational approaches prescribed for disadvantaged communities often reduce reading to mechanical skill acquisition rather than meaningful engagement with ideas. The transformative literacy experiences that build complex and confident thinkers with text rarely occur in classrooms focused exclusively on phonemic awareness exercises.

Based on the report Humanities Education in California: Access, Enrollment, and Achievement (2017), there's clear evidence of disparities in humanities education between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds. Schools with higher concentrations of low-income students offer rigorous humanities courses less frequently than schools serving wealthier populations. Low-poverty middle schools offer more than twice the number of foreign language courses than high-poverty middle schools (72% vs 28%).

Advanced courses in history/social sciences are more frequently offered in low-poverty schools (e.g., AP U.S. History is offered in 83% of low-poverty schools vs 68% of high-poverty schools), though lately affluent schools have been withdrawing from the AP program because the courses are too easy. Moreover, affluent schools are concerned about the idea of “teaching to the test.” Advanced visual and performing arts courses (like AP Music Theory and AP Art History) are offered primarily in schools in the lowest poverty quartile.

There is also clear evidence of disparities in student enrollment in humanities courses. Students in low-poverty schools enroll in advanced humanities courses at significantly higher rates than their peers in high-poverty schools. Specifically, in history/social science and foreign language subjects, students from more affluent schools participate in advanced courses at nearly twice the rate of students in high-poverty schools.

An interesting pattern emerges with Spanish language instruction: while both high-poverty and low-poverty schools offer advanced Spanish courses at similar rates, students in the lowest-poverty schools enroll in these advanced courses much more frequently than socioeconomically disadvantaged students. This enrollment gap represents another dimension of the educational divide that extends beyond mere course availability.

Only 35% of disadvantage students met proficiency on the 2016 SBAC English assessment vs. 69% of non-economically disadvantaged students. More recent data suggests that socioeconomically disadvantaged students statewide made gains in proficiency rates, but the gap remains significant. On history exams, not-socioeconomically disadvantaged students performed nearly twice as well as socioeconomically disadvantaged students.

Although this report is several years old and limited to California, given that California represents perhaps the most diverse state in the country, the report is moderate confirmation that these disparities in access and enrollment likely contribute to achievement gaps on K-12 assessments where wealthier students consistently outperform their peers from lower-income backgrounds in the Humanities.

Corporate America has noticed the good will they can buy, of course, by pouring millions into literacy programs. Moreover, corporations need labor, and ever increasing demands for skilled knowledge workers brings a touch of self-interest to the calculus. For example, tax credits like the Educational Improvement Tax Credit (EITC) in Pennsylvania provide incentives for businesses to invest in literacy programs. Companies receive substantial tax credits for donations to approved organizations. Perhaps the most valuable lesson in literacy, after all, is learning to read between the lines of profit-loss statements if all children were to learn to read great writers and philosophers like the wealthy and the powerful.

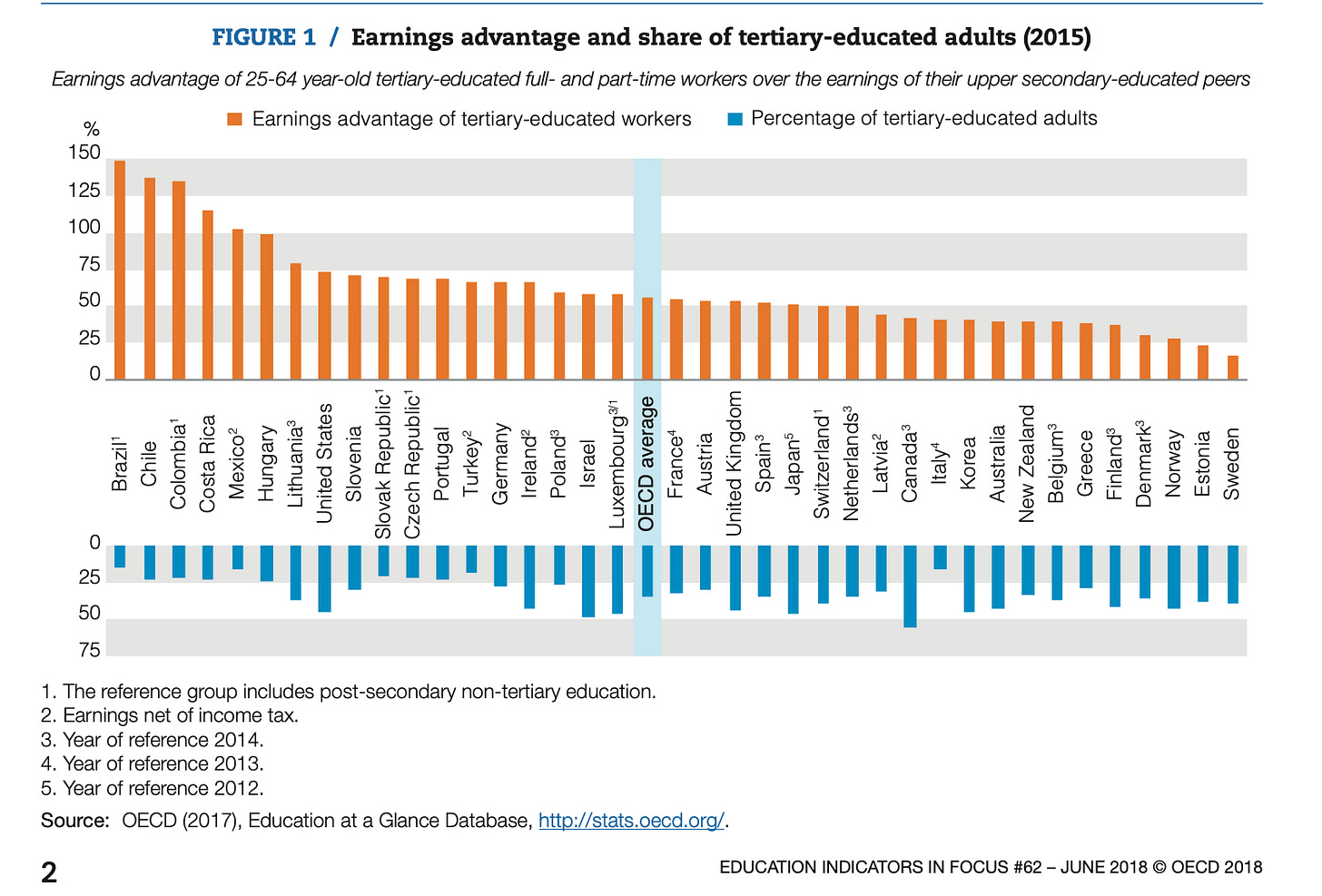

The intricate relationship between literacy, economic prosperity, and educational philosophy presents a stubborn paradox in American society. Green, symbolizing both sociocultural and environmental awareness as well as financial prosperity, is an apt metaphor for understanding literacy's dual nature as both a humanizing force and an economic driver. This pattern is not limited to the United States. The following graphic tells the tale (OECD, 2018):

For clarity, these earnings figures are standardized to 2012 US dollars using Purchasing Power Parity (PPP) rates, making them comparable across different economies regardless of local currencies or cost-of-living differences. The data specifically refer to full-time workers (30+ hours weekly) between ages 25-64 with employment income. This standardization allows for meaningful cross-national comparisons while controlling for educational attainment, revealing the distinct impact of literacy skills independent of formal credentials.

The OECD data reveal a consistent and substantial "literacy wage premium" that transcends formal educational credentials, demonstrating that advanced literacy skills independently drive higher earnings across all educational levels. According to this report, adults with high literacy skills consistently earn substantially more than their less-literate counterparts across all educational levels. Tertiary-educated workers with high literacy levels earn about $4,000 per month, while those with tertiary education but low literacy skills earn approximately $3,000 per month.

This difference becomes even more pronounced in countries like the United States, where the gap can reach about $2,000 per month between those with high and low levels of literacy. This “wage premium” isn't limited to those with college degrees. Remarkably, adults with upper secondary or post-secondary non-tertiary education who possess high literacy skills often have higher monthly earnings than those with tertiary education but lower literacy skills. This suggests that literacy skills themselves, rather than formal credentials alone, drive significant portions of earning potential in the modern economy.

For women, data from 2012 indicate that the literacy gap in earnings in the United States is particularly severe. Women with low literacy skills reported very low earnings overall and substantially lower earnings than those among comparable men. While both genders benefit from strong literacy skills, women see much greater relative gains from high literacy than men. Women with high document literacy are 94 percent more likely than women with low document literacy to make between $650 and $1,149 per week and 353 percent more likely to make between $1,150 and $1,949 per week.

Though a strong male advantage persists among the highest earners, high literacy may help women reach earnings levels that allow them to support themselves and their families. Research from 2024 concluded the following with reference to women and digital literacy: “This study highlights the significant impact of digital literacy on women's economic empowerment. By addressing the factors hindering women's participation and implementing effective strategies, we can empower women to realize their full potential and contribute to societal development.”

Beyond individual earning potential, literacy levels significantly affect the broader economy. Forbes reported the results of a Gallup study commissioned by the Barbara Bush Foundation for Family Literacy (2020), finding that low literacy levels among U.S. adults could be costing the economy approximately $2.2 trillion annually, equivalent to 10% of the gross domestic product.

If all U.S. adults were able to move up to at least Level 3 of literacy proficiency, it could in theory generate this additional $2.2 trillion in annual income for the country. The study defines illiteracy as scoring below Level 3 on the Program for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC) literacy scale. Adults at Levels 0-1 struggle with basic text comprehension, Level 2 can make simple comparisons but can't properly evaluate sources, while Level 3+ individuals can evaluate sources and infer complex meaning.

Again according to the Gallup study, this economic impact in the United States varies by region. States with disproportionately high percentages of adults with low literacy levels stand to gain the most economically from improving literacy skills. For example, in Alabama, an estimated 61% of adults fall below Level 3 literacy, and bringing them to Level 3 could generate gains equivalent to 15.6% of Alabama's economy. Urban centers also would benefit significantly, with the nation's largest metropolitan areas potentially gaining at or just above 10% of their contribution to GDP by bringing all adults to a sixth-grade reading level.

Corporate America faces a literacy crisis that cannot be addressed through phonics instruction alone, no matter how systematically it's delivered. Even advocates within the Science of Reading movement acknowledge that comprehensive literacy development requires knowledge building, oral language development, robust vocabulary and conceptual understanding, writing practice, and engagement with literature from the earliest stages of education.

The evidence is clear: developing proficient readers requires scaffolding their sustained motivation—yes, motivation can be learned—and metacognitive awareness; challenging them to engage in productive individual and participatory struggle beyond rote learning; and providing meaningful participation in authentic literacy communities—what Frank Smith called “joining the literacy club.”

To meet the demands of knowledge and human improvement workers in today's economy, especially with language machines in our future, becoming a truly critical reader necessitates immersion in the humanities—precisely the educational experience our society routinely provides to children from privileged backgrounds while often denying it to others. The economic data confirms what educators have long understood: true literacy is not merely a technical skill but a transformative capacity that enables full participation in both economic and civic life.

Everyone argues over wages and policy, but if you can’t read well enough to understand the system, you’re already at a disadvantage. Literacy isn’t just for books—it’s a necessity in an economy that expects you to keep up.

Well-said, Terry! It is a critical skill that needs to be taught early - and sustained. Instant gratification tools have not helped. The rise of video has not helped.