Overscaffolding and Underwatching: A Treacherous Riptide for Learning

Warning: My biases are on full display.

There are times when capital T Theory should have its say, when a touch of hegemonic scientism is appropriate to inspire kneeling before the hooded ones—not enough to fuel dystopian Open Court liberalism, not enough to piss off the Mothers of Liberty, but enough to elicit the classic EF Hutton posture.

Scientism is a pressing social problem, and pushing this Theory on the school website probably isn’t a good idea. There is a problem. On one hand, Theories gain traction when people call them by acronyms. SoR, DRTA, QtA, FLIP—acronyms immortalize theories as explanations for the here and now. They are useful in centering the collective work of teachers with distributed professional roles to play. But Theories in many parts of the country are the province of parents and politicians. Being three capital letters, ZPD is too like CRT. Raising the banner of Science risks offending the Evangelicals and the antivaxxers not to mention the especially dangerous white supremacists for whom antiblackness is over.

But this Theory is such a godsend to teachers that coming together quietly without fanfare using available tools and resources in a social zone of proximal development, buying in, fidelity, trying as a whole school to examine the implications for collective pedagogical action is at least worth thinking about.

I actually think if a school had professional leadership in literacy, which can be achieved within current schools, adopting this Theory at the center of the school’s theory of pedagogy and human development could improve literacy outcomes. It could also improve professional growth opportunities for teachers. Given time, it could provide opportunities for parental growth as stakeholders in the school.

Whether you are a novice or an expert, there is something in the ZPD for you. I published a poem about this Theory titled Red Feet at Shakespeare’s Monkey a week ago much as poets throughout time have paid homage to a spiritual being. I would have enjoyed talking to Lev Vygotsky. So I’m signed in and on.

A dawning understanding came over me that I’ve been living for many years within a historical zone of proximal development since I read Lev Vygotsky’s Thought and Language over thirty years ago. I’d experienced short lived theoretical fascinations before with Meyer’s-Briggs personality theory in the 1980s. Even though sociocultural theory has washed the MB sorter from my brain, I still can tell an SJ from an NT. Two additional Big Ideas have echoed in this zone with me as the novice and Lev as the expert: Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed and Bakhtinian heteroglossia.

Recently I stumbled onto a study published in The Reading Teacher, Volume 74, 2020, written by Laura A. Taylor titled “Scaffolding Literacy Learning through Talk: Stance as a Pedagogical Tool.” (An elementary school without a subscription to this journal is like a pantry without flour. A school could easily afford to subscribe to all of the International Literacy Association’s journals for the price of one teacher’s online SrO course.)

Key terms in the title, in addition to adding to the searchability of the study in academic databases, carry rich theoretical weight. What is a scaffold? What is literacy? What is learning? If I were leading a professional learning network or even a grade-level meeting, it would be well worth exploring these questions in a safe setting at any level of teacher development in a school. These are among the questions I would want to talk about with Vygotsky. I’d also ask him about the red feet.

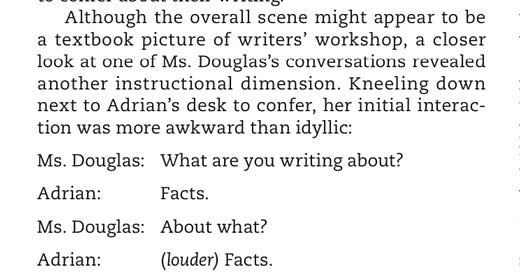

Personally, I thoroughly enjoy ethnographic studies done with a close lens on teachers and learners. This is where it really matters. I am not disappointed from the very start. Laura cuts to the chase and serves up a slice of data from her field record that I read as if it were a poem. Students are writing a book to honor a departing student teacher, Mrs. Geller. Ms. Douglas, the master teacher, is circulating to talk with the writers. Laura may not know at the time of observation the theoretical significance of this moment, but she documented it thoroughly in the moment for possible use as evidence and example:

Next, Laura elegantly explains that this teacher usually has productive interactions with her students—Laura knows because she’s been observing carefully and analyzing reflectively as I can tell from her expert scientific control of the ethnographic lens. She has been well trained to function as a scientific human instrument. I wasn’t born with an expert ethnographic lens nor was Laura, and we both were taught to honor the ethnographic scientist’s pledge to do no harm. How does one publish such intimate details of a teacher’s life in an unflattering light? When this teacher reads this excerpt, she will be touched by Laura’s sensitivity to her inner teacher spirit. She will be grateful to Laura for honoring her teaching with such careful attention, for finding an example likely to do good for others. There will be a sting, but it will morph into inner satisfaction.

If the change from sting to satisfaction is slow for Ms. Douglas, Laura’s clarity about the value of the observation speeds it up. This teaching moment, if unobserved and un examined, would have come and gone. As things turn out, it gives us all a rock to stand on as we look squarely into the face of the challenges of teaching inside a two-party ZPD inside the social ZPD of a classroom:

All of us are in the same boat. We all have awkward moments. The question is how do we go about learning from them. How do we adapt the amount and type of support we give? Can we label these awkward moments and talk about them?

As it turns out, Laura explains an evolving knowledge fund developing among other researchers about “stances” teachers can take to increase productive interactions with students in the zone. One ineffective stance researchers have labeled “overscaffolding” and have placed red flags in the theory:

Note the citations. Cut off at the top of the screenshot we see (2010) and we know researchers have been theorizing about scaffolding means for 22 years now. There is a distinction between means and stances. When teachers wonder “What are the means for making a scaffold?” there are scientifically derived answers—maybe imperfect, but real and useful, a good use of language as a psychological tool. What should be my stance in the moment? What criteria are helpful in making a decision on the fly? Two keys: support and challenge. What means can be used to support and challenge? Too little support, we have an awkward moment. The sinking feeling, the Southwest moment. Too much support, we have a lost learning opportunity. Overscaffolding probably flows from underwatching and relying on recipes—or? Heavy scaffolds take the risk of failure away, so careful observation isn’t all that important. In either case, under- or overscaffolding, the learner will lose not just the learning, but confidence in learning.

Laura embeds a clear sign that this study could scaffold growth among teachers even if the literacy leader is not an expert in Vygotsky. No one of us can be experts in all things. But we can gain familiarity from the article, and we can do these things:

Laura Taylor’s article is a great contribution to literacy leaders in the trenches. My post today is not very well polished, but because my previous two posts have drawn readers to them (though no souls have commented), I want to get it out. It’s linked conceptually to Reading the Science and Buying the Science posts, but instead of pontificating, it is pragmatic. I’ll revise it and update on the fly, all the better with your comments as scaffolding. Thank you for reading this series of posts.