“Trump…processes information orally. If you process information orally, you likely process little information. And if you process little information, you exude even less. Every time Trump comments on a subject, he reveals how little he knows about it. He wondered aloud why the Civil War was fought. He said he's been treated worse than Abraham Lincoln, who was assassinated. He didn't know what happened at Pearl Harbor. He's too dumb to know he's ignorant, and he's too narcissistic to care” (Windsor Mann, 2020, “Trumps Lethal Aversion to Reading,” The Week

The entanglements of meaningful differences in information consumption between orality and literacy looked at from an anthropological perspective are knotty and would distract from the focus of this piece—Donald Trump’s aliteracy. That’s the story. Before I explore the assumption that processing information orally is tantamount to processing little information (there are a few significant knots in this assumption), I want to characterize Trump’s reading habits related to the job of being President by comparing what we know publicly about President Obama and President Trump. Then I’ll address the issue of listening vs. reading raised by Mann (2020). Finally, I’ll discuss what little is available publicly about Trump’s experiences in school as a youngster.

Briefings

Consider the question of how each President approached briefings as a literacy event. A Presidential brief as a literacy genre or a discursive tool if you prefer has two parts, preparation for the event and norms of participation. Traditionally, briefing styles are adopted to adapt to each President. With roots in military history, the brief has two purposes in a tension: to provide complex information relevant to significant decisions quickly and succinctly to a layperson.

Preparation involves considerable demands on both writing and reading. Lengthy documents are written on topics currently front and center on matters of national security and policy issues. Agencies like the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the National Security Council (NSC) route these documents to the administration with the expectation that the President will read them to a) give them an advanced organizer about the topic, which will be discussed succinctly, b) build contextual, historical, and situational knowledge essential to grasping the push and pull of the significance of information, c) gain familiarity with the options and recommendations for action beforehand to flag and note questions.

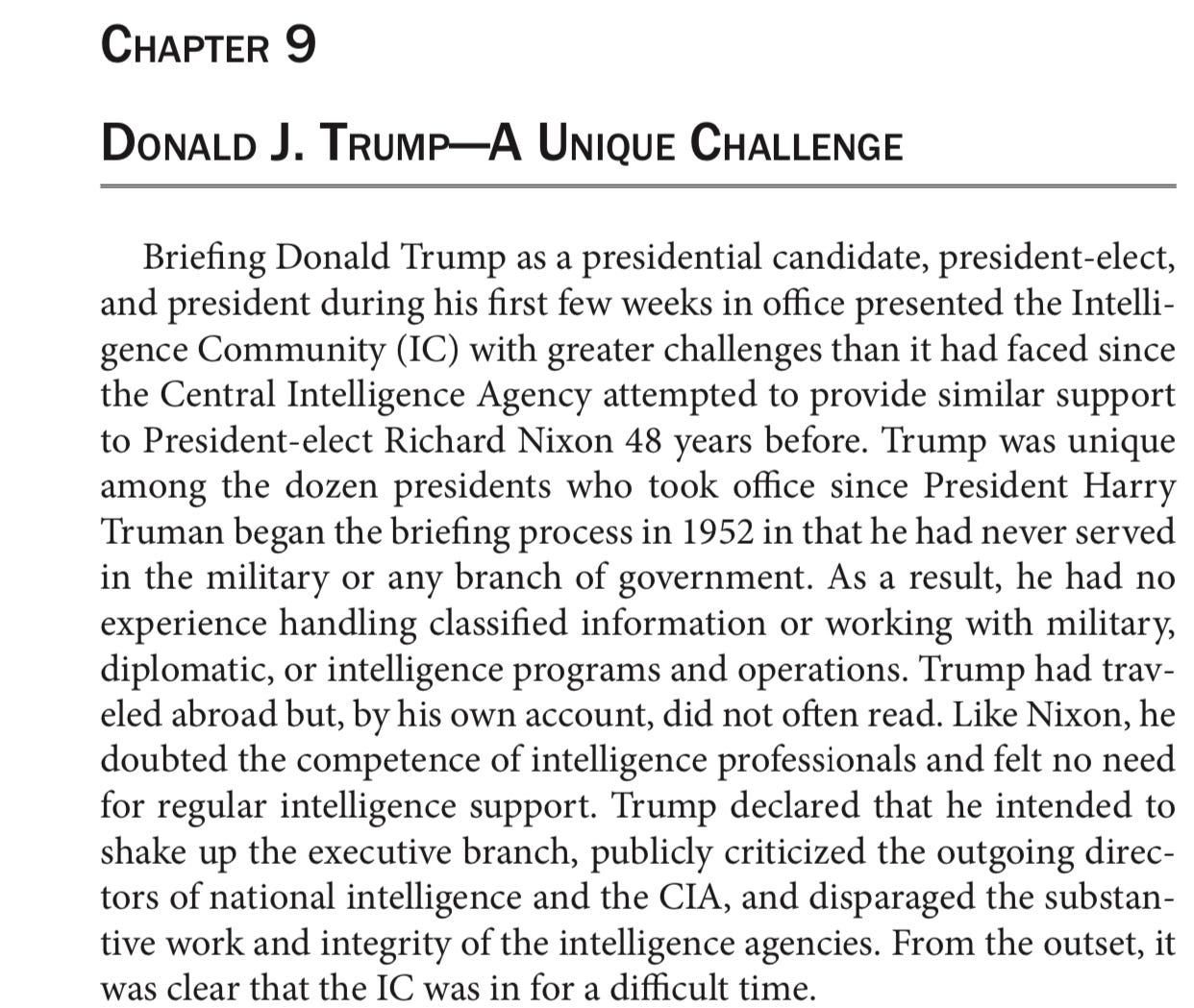

Guess what? All of the evidence reveals that Donald Trump did not read them. At night he sat in his room munching on French fries and hamburgers watching Fox News. In fact, reports abound that Trump usually did not attend daily briefings—Mike Pence did. In the fourth edition of an Intelligence report updated every four years titled “Getting to Know the President” Chapter 9 titled “Donald Trump—A Unique Challenge,” the following introductory paragraph sends shivers through me:

For purposes of contrast, consider media reports of President Obama’s uptake of daily briefings:

“For Obama, the PDB process paints a portrait of a methodical president who's often disdainful of raw, unfiltered intelligence in favor of more analytical perspective. He encourages dissenting opinions. He's interested in ‘open source’ intelligence — including press accounts and, increasingly, social media — in addition to old-fashioned spycraft and intercepted communications.” (Gregory Korte, 2016)

The briefing agencies learned quickly that President Obama preferred detailed, in-depth written briefings delivered on an iPad. He often requested extensive documentation and patiently deployed academic reading strategies honed through years of legal, historical, philosophical, and literary study and reading. Obama's approach was methodical and studious, reflecting an individual with habits of mind that valued detailed analysis linked to a comprehensive understanding of issues before discussing them.

Reading or Listening: A Simple View

Now to the matter of getting information orally or in written form. In the quote that opens this post, the writer asserts that processing information orally entails processing less information. Most reading scientists would agree that evidence reaching back to Vygotsky establishes that higher-order, formal analytical cognition is the consequence of formal schooling, not of reading. The capacity to think with language written or spoken is learned through agency in situated activity settings like classrooms, not through some generic concept of reading, writing, or even speaking and listening.

That said, there is scientific evidence putting limits on the speed at which humans can read—assuming to read means at a minimum to understand the information within a context in enough detail to summarize it with appropriate elaboration. Basically, you can say “I read this book” when you understand the contents of what you have read.

The novel Jaws by Peter Bentley (1974) caught my attention during my third year of college. It was unusual for me to read anything that wasn’t assigned for a class, a phenomenon I experienced for the next three years or so, but I picked it up in a bookstore and got hooked. When I got back to the dorm, I started reading the book and finished in just over 45 minutes. There was nothing scientific about it, but I learned that reading speed is related to cognitive demands. By the way, Stephen Spielberg is said to have said he disliked all the characters and wanted the shark to win. I’m sure I skimmed as much as I read.

Rainer and Pollatsek (1989) put to bed any principled judgement that humans can “speed read” in the sense of drawing one’s finger down the middle of a column of print as a pacing device, taking in whole lines in one fixation by way of maximizing peripheral vision, perhaps using context. If we take the careful reading of text as the criterion behavior, the Obama way, as distinguished from skimming for a passing familiarity like my reading Jaws, reading speed at criterion is limited both cognitively and neurologically.

Rayner and Pollarsek (1989) presented evidence that college readers normally read between 200-350 words per minute. Faster rates produce declines in comprehension likely because skimming behavior takes over, portions of the text are skipped, and surface processing is the result. In my case, surface processing of the shark story worked just fine. “…[W]e make eye movements every 250 milliseconds (on average) to bring a given region of text into foveal vision,” they wrote (p. 441). Essentially, readers of script with a left to right sweep have a span of four letter spaces to the left and up to fifteen letter spaces to the right in a single fixation followed by a saccade, or a movement to the next fixation. In contrast, normal speech rolls in around 140-150 words per minute. Reading 2,000 words per minute doesn’t happen with human eyes.

So it’s wrong to say that Donald Trump is deeply misinformed because he processes information orally. It’s also wrong to say that Donald Trump is stupid because he doesn’t read, though I’m almost ready to delete this sentence as I write it. The signal system would make processing quantitatively different—oral is slower—but the critical point is a difference in thought processes. According to Bolton’s account, Trump can’t hear any information that goes against the grain of what he wants to hear. It wouldn’t matter whether the information came from a document, an audio recording, or from the horse’s mouth.

No doubt Trump’s aversion to reading has left a gaping hole in his knowledge of the world, if for no other reason than reading, say, Doris Kearn Goodwin’s Team of Rivals isn’t going to be replicated in ordinary speech. There is no evidence that he is an avid listener of audio books. Over time, the extra 150 words or so gained from reading silently would add up.

Listening at a rate of 130 words per minute translates to 9,000 words per hour. Reading at a rate of 250 words per minute translates to 15,000 words per hour. Oral consumption of information through listening for 1,000 hours yields consumption of 9,000,000 words. Silent consumption of information for 1,000 hours yields 15,000,000 words. Listening 1,000 hours per year over a lifetime of 75 years translates to 675,000,000 words. Reading 1,000 hours per year over the same span translates to 1,125,000,000 words. Writers Digest estimates that the average length of a commercially viable novel is around 80,000 words. Figures change based on the age of the reader:

All of these numbers are highly theoretical. In reality, the quantity of information taken in through listening is likely much less when you account for time spent talking rather than listening. Trump usually does most of the talking, showing great impatience when he has to listen—for example, when he is sitting in a courtroom as a defendant. Plus when one is reading, one isn’t literally talking back every minute or so. Reading has a way of nailing down words that seems to focus the mind. Nonetheless, it all reverts back to qualities of thought, much of which comes from school. Reading well for most of us is the result of doing well in high-quality formal classrooms across the curriculum.

Donald Trump’s Schooling

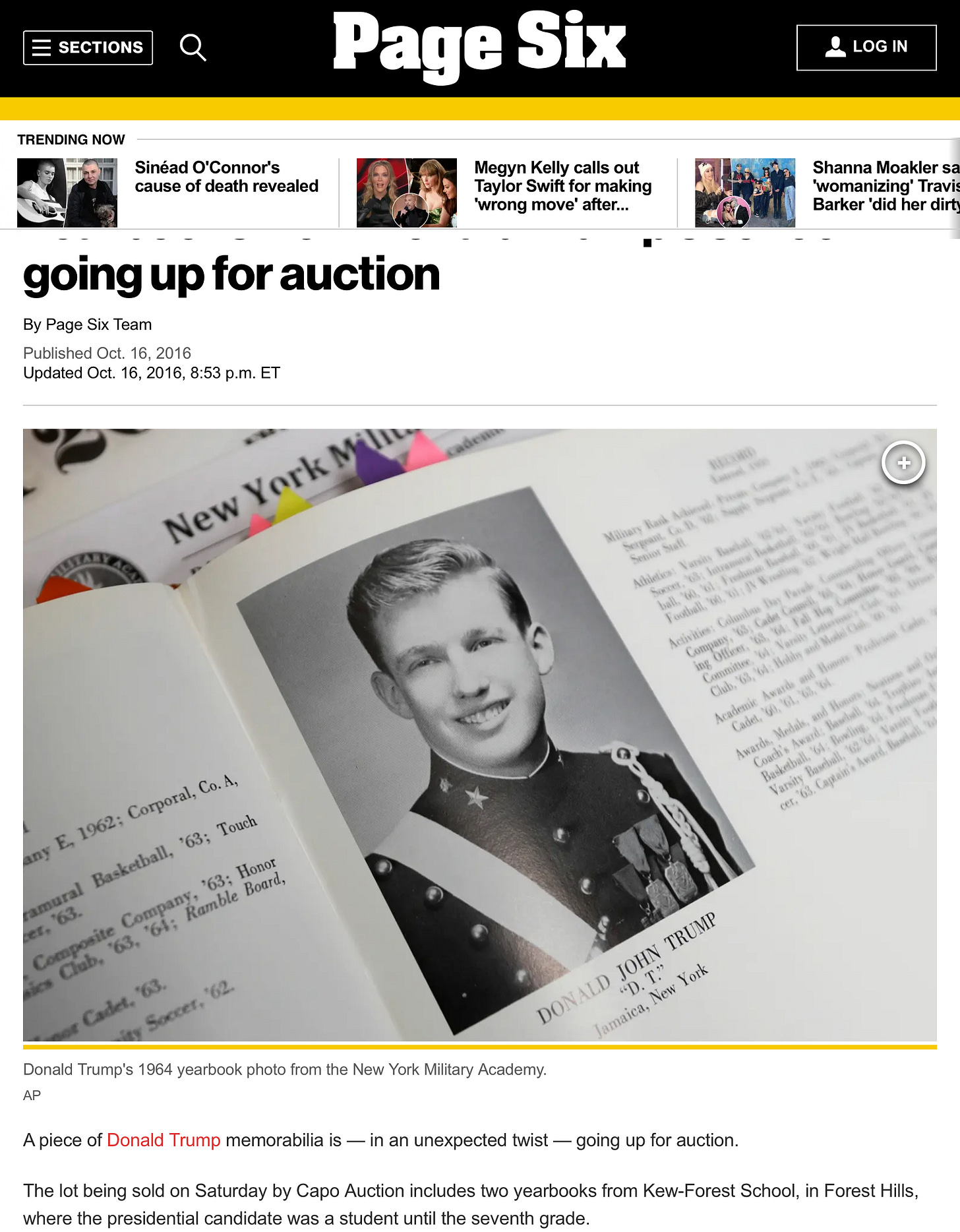

Very little is publicly known about the details of Donald Trump's early elementary grade experiences. Given that Trump was born into an affluent family in Queens, New York, and attended the private Kew-Forest School from kindergarten until seventh grade, it is reasonable to infer certain elements of his early education.

Attending Kew-Forest likely means that Trump's early education took place in a well-resourced setting with small class sizes and considerable attention from teachers. I searched high and low for any evidence of how he was assessed by his teachers but came up empty handed—his report cards may be in David Pecker’s safe in the basement at the National Enquirer where salacious stories about his past safeguarded by non-disclosure agreements are stored. ““When I look at myself in the first grade and I look at myself now, I’m basically the same,” Trump once told a biographer. “The temperament is not that different.”

In the same report published by the Washington Post, a teacher who saw Trump make his way through the grades described him as a holy terror:

“‘Who could forget him?’ said Ann Trees, 82, who taught at Kew-Forest School, where Trump was a student through seventh grade. ‘He was headstrong and determined. He would sit with his arms folded with this look on his face — I use the word surly — almost daring you to say one thing or another that wouldn’t settle with him.”

One anecdote about Young Donald is his transfer from Kew-Forest School to the New York Military Academy at the age of 13. While specific reasons for the transfer are hard to come by, sources including Mary Trump say that behavioral issues became intense. This move suggests that Trump was perhaps struggling with the structure and discipline of a traditional school environment in much the same way he struggled with the structure and discipline of being a President.

In the 1950s, private schools like Kew-Forest emphasized a traditional curriculum with a strong focus on the basics: reading, writing, mathematics, history, and the sciences. The debate between phonics versus the whole word method to reading was raging in the 1950s, the decade when Rudolph Fleisch published Why Johnny Can’t Read, advocating phonics. Trump, like many students of his time, would likely have been taught reading using a phonics-based approach. Writing instruction in the 1950s included cursive handwriting and penmanship. Good handwriting was a sign of a person's education and character, and private schools emphasized its importance. Perhaps this early training accounts for his famous signature:

Exposure to literature was a hallmark of private school education. Students read and analyzed texts that were considered important works, which also in theory served to improve vocabulary and comprehension skills. Yet more than one biographer reported that Trump has never read a book. The only book he brings up is The Art of the Deal. Whereas President Obama routinely publishes lists of books he recommends (I learned about Klara and the Sun, a remarkable work of science fiction especially meaningful in the Age of AI, from President Obama), I can’t seem to find a single recommendation from Donald Trump.

.

He makes me scream. At what he says. I dont like it. I like calm plodding Biden. I hate Trump and his bravado and attachment to Putin. Ask any russian, without another russian listening, life has gotten very hard again, in that traditional russian way where theres dead everywhere in the name of mother russia and fatherland. No. America can be first in a different way.