Mosaic Plagiarism

Unattributed Patterns of Meaning-Language Particles Intended to Deceive During Peer Review

Researchers in advanced academic and professional schools are under increasing existential pressure to publish articles in order to progress in their field. Young researchers are judged and promoted up the ranks according to quantity of publications in respected journals, thereby gaining personal credibility as experts and enhancing the public standing of the institution. Funding sources award millions of dollars annually to support academics pursuing a research agenda with a strong list of influential publications. Among researchers in medical fields, pressure to publish is unusually intense today for a multiplicity of reasons. Expertise as a plagiarist, when it occurs, is motivated by a calculus of risk and reward, often banking on subtleties of style and voice to convince peer reviewers and journal editors of the integrity of mosaic obfuscation of a source. It’s hard to count occurrences of mosaic plagiarism because the most accomplished artists are never caught.

“The American Medical Association Manual of Style[17] describes mosaic plagiarism as ‘… borrowing the ideas and opinions from an original source and a few verbatim words or phrases without crediting the original author.’ In this case, the plagiarist intertwines his or her own ideas and opinions with those of the original author, creating a confused, plagiarized mess.” (Das & Punjabi, 2011)

Note the doublet ‘ideas and opinions.’ Don’t take up someone else’s perspective on a thing and lead others to believe it’s your perspective. Own your point of view and honor that of others by acknowledging them and signifying them by name. The effect of disloyalty to the scholarly code of academic ethics is to blur the line between the borrower and owner of the original language and meaning. Who is speaking? wonders the reader once the authorial voice loses its perceived integrity.

What makes mosaic plagiarism so insidious is the difficulty in detecting it when done well and the damage it does to trust in science and journalism and in Gricean communicative agreements. The Science of Reading, as a cult in my opinion to borrow a word I’ve heard and read in reference to SoR a zillion times, has become a national hallucination largely via mosaic plagiarism—few lay advocates know what they are talking about beyond what they’ve taken from sources. Cult meaning-language particles in patterns are self-plagiarized, blatantly copied without attribution, and synthesized into mosaics in the discourse of SoR as its lifeblood.

As Das and Punjabi (2011) pointed copying, theft of original ideas (a peer reviewer rejects a manuscript, steals the idea, and publishes a paper) or a blatant cut-n-paste are more easily discovered and prosecuted. Not so with mosaicism wherein a writer’s own words—and opinions—are blended when convenient with another writer’s language and meaning in a deliberate effort to avoid detection. According to Das and Punjabi (2011)—

“If a reviewer places two documents together and it is obvious that some text in one has been copied from the other, he can then label it as a plagiarized article. In Sapatnekar’s words,[11] ‘To do this (plagiarism) overtly demonstrates your brashness. To do it covertly amounts to cowardice. To do it efficiently qualifies as an expertise; since ultimate success of a theft essentially lies in the theft passing undetected.”

One might argue that this problem in the medical literature is trivial in that medical research is heavily scrutinized for the very reasons researchers are under pressure: Human beings need medical science. An occasional case of plagiarism is unlikely to result in mass deaths, especially if the plagiarist used solid ideas but just didn’t acknowledge the source. But the underlying breach in integrity and the erosion of academic self-respect among the most highly educated professionals bespeaks a need for deep, systemic training on appropriate participation as a reader and writer beginning in childhood and sustained in adolescent classrooms, especially now in the era of the bot. Habits of mind intended to deceive may be too deeply engrained by the time young adults experience their undergraduate years.

In elementary school beginning as early as second grade students are assigned the task of writing a report about ordinary topics like an animal or a place or a planet; finding sources, reading them, and copying relevant information into one’s own paper is often unsupervised instructionally. I asked the bot to write a sample report a second grader might produce. Witness:

Such assignments may be motivated to completion more by the desire to get approval from a teacher or from parents than by any authentic impulse to communicate a personal perspective. Even if the student cut and pasted from a website (or used a bot), one is hard pressed to explain how these facts are the property of the author who happened to express them in a book or on a website. The assignment itself disguises the significance of acknowledging sources and foregrounds the value of cutting and pasting information. I asked the bot to create a reference list for this paper. Witness:

Rewarding students for taking the initiative to find and copy information in a coherent way reinforces assignment compliance behaviors but sends ambiguous signals about plagiarism. The experience naturally is shaped by socioeconomic and geographic factors for sure—access to libraries, to technology, to attentive (helicopter) parents or guardians in more affluent communities, less access in rural and urban communities. This access can influence the depth of research, quality of sources, and availability of supportive materials for report writing. But it does nothing to build understanding of academic integrity in disciplinary contexts.

Students are often at a loss to understand why they need multiple sources. Often, they find way more information than they need in just one source. Many students come to believe their job is first to find the information, then to transport the information from one text to another, and then to dump that information. Since information comes in words, words get dumped. In fact, writing researchers in the 1990s referred to such “research papers” or “library papers” as “information dumps.”

*****

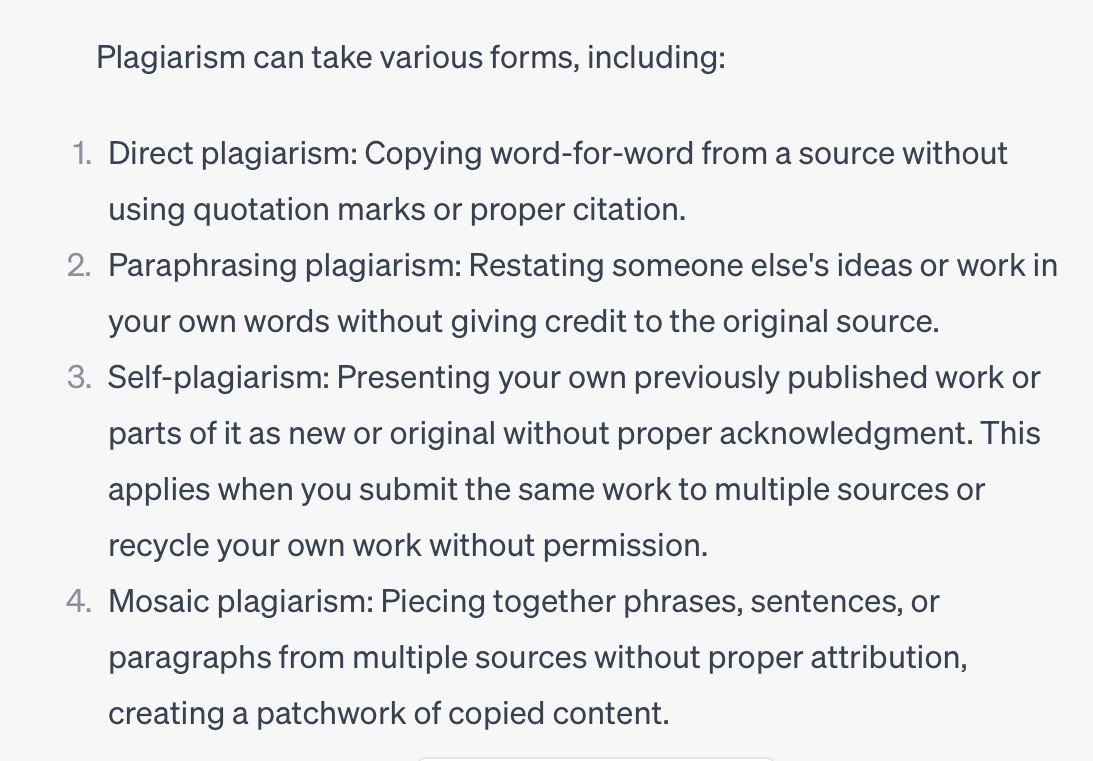

I decided to turn to the bot to see what I might learn. I began with a simple request for a definition of plagiarism:

I became intrigued with the phrase “mosaic plagiarism,” a term I had not encountered. I realized that the bot had already admitted that its “writing” is entirely mosaic plagiarism when it told me that it could not create a reference list for the paper it wrote on dolphins. “A patchwork of copied content” aptly describes what the bot said it compiled when it wrote the simulated dolphin essay.

This list presented me with a familiar enigma. Type 1 (blatant copying) and type 3 (turning in a paper written for another class) are pedagogically non-complex, though it’s important to understand the learner’s motives and intentions as a basis for teaching them. Type 2 and Type 4 seemed fuzzy. Paraphrasing has always been a gray area; mosaicism in this context was new to me. So I searched Google Scholar and looked at several sources, one of which I cite above (Das and Punjabi, 2011).

I thought about paraphrasing and wondered what the bot would say about directly teaching it. So I hazarded a question getting at instructional opportunities through the back door:

Of course, paraphrasing is always a better bet than verbatim copying if the goal is to avoid detection, and GPT4 pointed this out. But something else was happening in its own beam scanning of meaning-language particles it learned during its intense training in the entire corpus of Wikipedia, which is also incessantly in need of source citations [needs citation]. Paraphrasing is a skill that can engage a writer in critical as well as rhetorical analysis. There is something to teach here:

There was no specific audience nor context for the animal report; so there was no reason to paraphrase. We were onto something, me and my bot. Paraphrasing, even close paraphrase, becomes a strategy a writer can use to shape information from a source for an original purpose, namely, to explain to my classmates what I learned about dolphins. It makes sense for me to cite the source—that’s important in case my classmates want to read more. I started examining the verbs the bot used in making another point about the value of paraphrasing not as a way to avoid a penalty but as a tool for learning:

Integrating information into my own work—now that’s something to think about. How can I integrate what I learned about mosaic plagiarism into my post on—what—-academic integrity in the age of ChatBots? Not just pasting in words, not just searching for new words to say the same thing, but integrating, weaving information from sources into my work, using it to help me understand, using distinct public voices and citing them, formulate my own thoughts, speaking my own thoughts to an audience. So to the bot I said—

It seemed to me that the bot jumped on this request. Sometimes, I see a long think time in the form of a blinking cursor. Sometimes the bot stops thinking. I have to click on “regenerate response.” A few words pop up, then more, then a burst of text. This time the response was instantaneous, a whole essay, as if the bot had been bursting at the seams to communicate:

Never mind that the bot itself is plagiarizing before my very eyes. Where did these ideas come from? It has no idea. Puzzle pieces showing how things fit together, mixing colors, getting to think and understand, becoming an expert, teaching others—the pleasure of making sense for yourself, creating your own big picture, being an expert, these come from paraphrasing. Yet there is more:

*****

Students will integrate, synthesize, and take up different perspectives on information from sources in their writing through paraphrasing and acknowledge the source of information inside the text or in a reference list. It helps me sometimes to take a try at articulating a teaching objective. Isn’t paraphrasing in this sense a close cousin of reading comprehension? I thought I might get some more assistance from GPT4:

Now write something that speaks to high school students:

Still, we need a strong, clear message about the steep costs of plagiarism for the writer, for the reader, for the community, for the world. Taking the easy way out cheats everybody. Sadly, the greatest cost is born by the writer who loses the opportunity to become an expert able to speak their mind confidently and cogently:

*****

My chat with the bot helped me crystallize my sense of the scope of the pedagogical problem of plagiarism. But I felt as if I had just scratched the surface. Pulling together the ideas of assigning report writing in a rhetorical context and providing modeling and instruction in paraphrasing was unsatisfying so far. I’ve never been satisfied with how I approach instruction in this aspect of literacy. For one thing, a fake rhetorical context is almost as ineffective as no audience or purpose at all, in my opinion. If I can’t draw on a real purpose and audience, I’m still simulating the reason people write reports, playing at it in the classroom. Building skills necessary to safeguard integrity is hard to do in a fantasy.

Paraphrasing as the bot reminded me to think about it is technically useful, but it doesn’t reach to the core of the problem, i.e., evoking authentic motivation, inspiring learner agency, cultivating respect for academic integrity. Hmm… I recalled an article I read a few months ago… Cervetti and Pearson (2023)… Yes, let me read it again… So I did, and I started work on Part 2 and will post it soon.