The argument for “phonics only” beginning reading instruction in first grade makes a lot of sense until you begin to grasp the complex role of the three-cueing system as a theoretical model representing interactions among meaning, structure, and spellings unique to reading. It’sn’t ez 2 prehendcom redders how due their cents making to less more is 2 it than sounding words out.

To tell you the truth, I’ve yet to see an argument from the phonics first advocates that convinces me that the proponents of this direct instruction in phonics first perspective have a solid grasp of the nuances of miscue analysis. I see it in the language they use—the “simple” view, “errors” as opposed to “miscues,” conflating the “visual” cueing system with pictures in a book. Clearly, they understand phonemes, graphemes, vowels, consonants, consonant blends, diphthongs, syllables, affixes, and all the rest—all the surface features of words in print. But the tough stuff in reading goes on beneath the surface. In my view, it’s a mistake to encourage a beginning reader to develop the mindset that reading is pronouncing words while ignoring what reading actually entails.

Let’s start with the word “miscue” itself. I'll compare and contrast the meanings of "miscue" and "error" as rhetorical terms, i.e., terms used persuasively. Both "miscue" and "error" refer to mistakes, but they have different connotations, contexts, and implications. The term "miscue" originally comes from billiards and pool, referring to when a player's cue slips while striking the ball. It has since been adopted in various fields to indicate a minor mistake that leads to misunderstanding or confusion. A miscue suggests a slight misstep that causes the audience to misinterpret the intended message. It implies something unintentional and often subtle like using an awkward phrase that confuses listeners.

The word "error" comes from fascinating etymological roots. It entered English around the 13th century from Old French "error," which itself came from Latin "errorem" (nominative "error"). The Latin term meant "a wandering, straying, a going astray; meandering; doubt, uncertainty" and also "a figurative going astray, mistake." It derives from the Latin verb "errare" meaning "to wander; to err" and has a broader and more formal connotation. Errors aren’t usually subtle. They stick out like a sore thumb. In a rhetorical sense, an error suggests a more substantial mistake in reasoning, argumentation, or presentation. Rhetorical errors include logical fallacies, factual inaccuracies, or significant flaws in structure. "Error" carries greater weight and suggests a more serious deviation from correctness or accuracy.

The concept traces back to Proto-Indo-European root “ers-” meaning "be in motion, wander around." Interestingly, this same linguistic root connects to words in various languages that reflect the notion of wandering or straying: Sanskrit "arsati" ("flows"), Old English "ierre" ("angry; straying"), and Gothic "airziþa" ("error; deception") (Etymonline). The link between error and wandering and going astray appears in many Indo-European languages. So at its core, "error" doesn't simply mean a mistake or incorrect answer. It carries the deeper connotation of “straying from the proper course or path.” This wandering metaphor gives the term more fire and brimstone than just being wrong; anyone can make a mistake. An error suggests deviation from truth or correctness as a kind of journey that has gone off track. Errors can be egregious.

One doesn’t often come across an “egregious miscue.” A miscue is generally viewed as less severe than an error, more of a slip up than a ground floor flaw. Miscues are almost always unintentional while errors can be either intentional or unintentional. Miscue tends to be used more in performance contexts (speech, debate, presentation, reading aloud), while error is used more broadly across written and spoken rhetoric. A miscue might momentarily confuse an audience, but is often recoverable, while an error can undermine the entire rhetorical effectiveness of an argument. Miscue suggests a slight miscalculation or misstep that leads to misunderstanding, while error denotes a substantive problem with the content or structure calling for systematic attention.

The key difference between viewing a reader’s mispronunciation, substitution, omission, or repetition of a word when reading out loud as either a miscue or an error lies in the assumption that readers always respond first to the spelling of every word they read, pronounce every word correctly, and then and only then make sense of the word in that specific sequence. In other words, we…..read…..one….word….at….a….time….and….link….them….together….like…..beads…..in….a…..necklace.

If a reader accidentally reads the word “link” as “join” or “lunk” or “pink,” it counts as an error. End of story. Seen as a miscue, “lunk” is more serious than “join.” Why? Because “join” is a verb like “link” (grammar) and preserves the meaning (semantics), suggesting the reader is comprehending, while “lunk” is neither a verb nor a meaningful substitution, suggesting the reader is not trying to comprehend but to pronounce words. From a phonics perspective, all errors are created equal, and it doesn’t matter what might have been going on in the reader’s sense-making. From a three-cueing perspective, what is going on in the reader’s mind is all important. “Join” is seen as a “guess” from the phonics perspective. From the miscue perspective, “join” is seen as evidence that the reader is attending to the message of the text.

Ten weeks of phonics in first grade is held up as the best way to immunize children from “guessing” words rather than “decoding” them. Teaching children to “guess” words, according to the phonics first folks, is the main problem with the cueing system as a way of teaching. In fact, teachers who embrace miscue analysis as a pedagogy are all in favor of accuracy—but they also are in favor of developing the mindset in young readers that reading is about comprehension as well. The prized behavior for phonics is pronouncing every word correctly whether they make sense or not, never straying from the truth. The prized behavior for miscue-oriented teachers is self-correction at the point of miscue when comprehension has been compromised. Phonics knowledge comes into play as a corrective tool as well as a decoding tool.

The “visual” cueing system has literally nothing to do with pictures or photographs that might help a child guess a word, as phonics proponents have led the world to believe. I cringe when I hear this argument from phonics first advocates; it reveals a fundamental lack of understanding of miscue analysis. This isn’t to say that kids never use pictures to help them figure out a word in a pinch, but it’s not like miscue pedagogy encourages kids to search for pictures rather than scrutinize printed words. Reading Recovery teachers using miscue analysis value phonics just as highly as anyone else—it’s just that phonics is one tool, not the entire reading process. Teaching phonics is part of teaching reading, not a sure fire way to start teaching reading to every child.

“Visual” in the psycholinguistic model means “attending to the letters in words.” It does not mean attending to the pictures. Anyone who claims that those who oppose scripted phonics materials or ten weeks of phonics in isolation in first grade also favor having kids “guess at words” or “ignore letter-sound relationships” or “take a look at the picture” misrepresent the nature and function of the “visual” part of the three-part word identification cycle as it is taught in Reading Recovery.

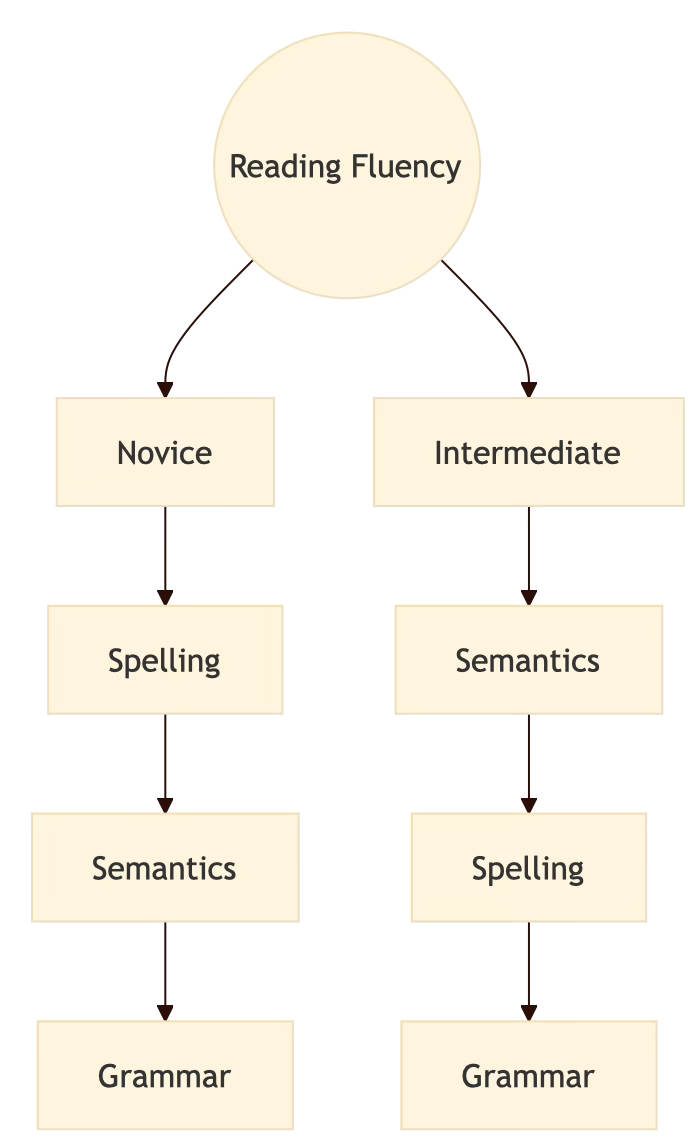

Having taught a full semester graduate course focusing just on miscue analysis when I taught at Illinois State University, which at the time was a regional training center for Reading Recovery, I’ve had the opportunity to roll up my sleeves and work with a wide variety of miscue types using these cueing systems. Most of the elements I see in the phonics first argument reveals a partial or superficial understanding of the concept. The following diagram depicts what the teacher must focus the reader’s attention on during oral reading using a phonics approach and also the phase shifting from decoding to comprehension once phonics has been mastered (Graphic prepared by Underwood, 2025):

The novice reader (beginner) must master the spelling system (sound-symbol correspondences) first. In other words, readers must be able to pronounce words in isolation based strictly on letter-sound knowledge. When sufficient expertise has been developed—usually assessed by counting errors on standardized lists of words in isolation, some of them nonsense words—students can be allowed to read connected text (words in sentences) with the expectation that they will eventually learn to make meaning from words in context (semantics). When students show that they are able to make meaning from grade appropriate texts, they are freed up to read real books for meaning. Instruction in the spelling system becomes less explicit and less systematic.

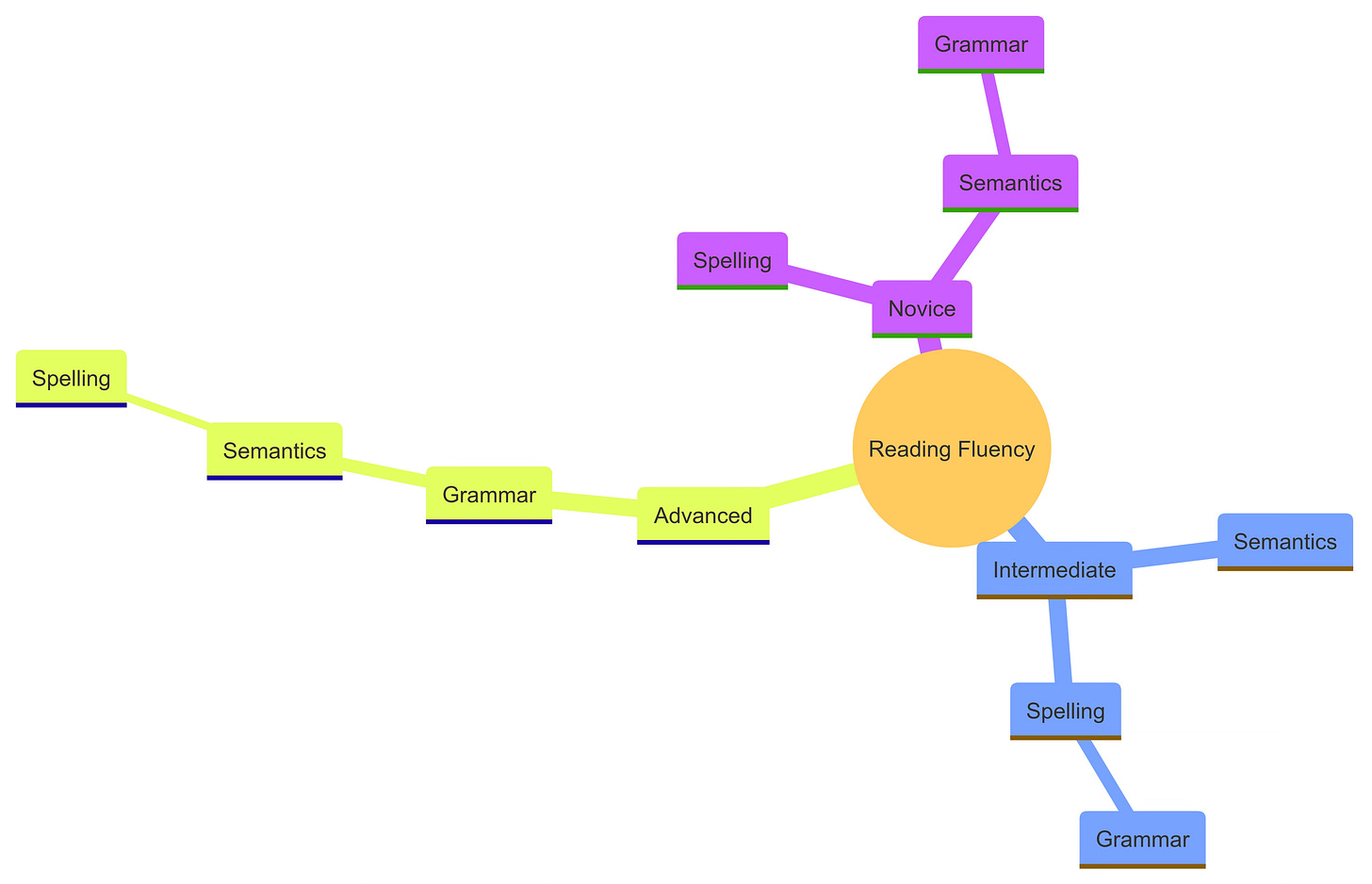

The following graphics (Underwood, 2025) depict how the debate about beginning reading instruction hinges on whether beginning readers should be taught to pronounce words in isolation for ten weeks or more before reading real books for comprehension or whether readers should be taught to read for comprehension from the beginning. Both sides agree that an elementary goal should be reading fluency, i.e., the ability to read words in sentences automatically and accurately with prosody. The crux of the difference resides in the novice strand of the graphic. Here I depict the phonics perspective, not the miscue perspective, where spelling is a separate topic for instruction, divorced from meaning or structure (phonics folks leave grammar and semantics to “listening comprehension”). The intermediate and advanced levels are essentially the same for both phonics and miscue work. Here, I posit that at the intermediate level teachers ought to focus on textual meaning and student response to it as a dominant pedagogical concern (building background knowledge, concepts, and vocabulary). More about the advanced level later.

Look again at the novice strand. Phonics advocates separate spelling (the visual cueing system) from semantics (meaning) and grammar (sentence structure). The first exposure to formal reading instruction is entirely around learning to apply paired learning associations between letters alone and in patterns to written words resulting in accurate pronunciations. Semantics and grammar are postponed until students demonstrate a standardized level of expertise in sounding out words in isolation.

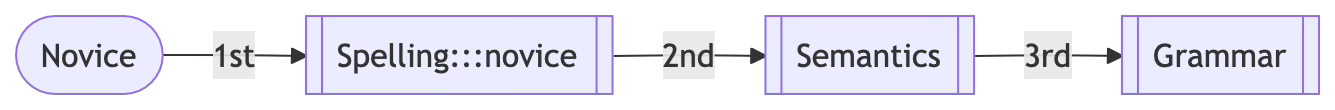

Miscue analysis instruction at the novice level looks like this:

Note that spelling is not separated from semantics and grammar in this model. The approach acknowledges that decoding using phonics is indeed a dominant focus for this developmental level. But in reading instruction, pronouncing words while reading is not separate from meaning and grammar. Indeed, learning to decode words accurately requires some direct instruction in phonics for most children, but the intensity of the need must be individually assessed by a well-trained teacher. The assumption that a) phonics must be taught for almost the first third of first grade apart from reading for all children as opposed to b) the assumption that teachers must assess all students for their level of phonics expertise and adjust accordingly—well, believe it or not, that assumption lies at the heart of the Reading Wars as they have been fought for almost a century now. Remember Why Johnny Can’t Read (Rudolf Franz Flesch in 1955) and Jeanne Chall's 1967 book Learning to Read: The Great Debate?

The advanced level has always fascinated me. Please refer to the full graphic above. Here, grammar, not spelling, not semantics, constitutes the first linguistic resource skilled readers draw on. Miscue analysis theory operates on the principle that meaning is grammatically structured in phrases and sentences. Meaning is impossible to communicate without structure. As a result, advanced readers read sentences, not words. For example, this classic sentence reveals how decisions about pronouncing words depend on other words in the grammatical context:

“He ran out of the woods with tears in his eyes and tears in his coat.”

In ordinary reading in uncontrolled circumstances, words must be disambiguated all the time. How do advanced readers do it? First, they read for structural relationships among meanings, they expect it, a mindset that can begin on the first day of first grade. Advanced readers don’t search for meaning one word at a time. The skilled reader begins reading words in relationship with other words and tracks the push and pull of semantics through grammatical transitivity. For example:

“To repair a stopped-up sink”: “To repair” expresses a chunk of meaning which pushes the reader toward a thing that must be acted upon or “a stopped-up sink” which isn’t the same as a “stopped-up stink” which would require a self-correction…

“…start by removing any visible debris…”: The reader must hold the first chunk of meaning in mind (to repair) and activate the meaning of “start,” a word that marks the beginning of what must be done to effect the repair articulated in the first chunk. You—yes, you, the sentence says, I’m speaking to you—must start “by removing any visible debris.” The “You” is not printed anywhere, but it must be in the sentence or nothing makes sense. The reader who has tacit knowledge of grammatical structure understands “removing,” and then is pushed toward “any visible debris.”

“…use…” something but what? “…a plunger or drain snake…” I’m not putting a snake in my drain…Oh! not that kind of snake! “to clear the clog” not the wooden shoe but the… “and, if necessary…” if that doesn’t work “…disassemble the P-trap…” What in the world is a P-trap? “…to clean out any blockages…” Hmm… P-trap… Let me check with a bot…

***

One Size Does Not Fit All

The phonics-first approach deserves credit for its clarity, structure, and empirical support. Who could argue with research that suggests phonics is important when the alphabetic script is used to convert speech to print? Who could argue with the neuroscientists who see the brain light up in regular patterns during decoding? Something is definitely happening with those letters, those sounds, and those loops firing in the brain.

Systematic phonics instruction provides beginning readers with an essential foundation in the alphabetic principle that underpins our writing system. Research consistently demonstrates that explicit phonics instruction benefits many children, especially those at risk for reading difficulties. The emphasis on accurate decoding creates a reliable pathway for children to access written language, and the sequential nature of phonics instruction offers teachers clear benchmarks for assessment and intervention.

However, while phonics is necessary, it is not at all sufficient as even the Simple View will tell you, and it can easily distort student mindsets if it is treated as though it IS “reading.” It ISN’T reading—no more than spelling is writing. The "simple view" of reading as merely decoding words in isolation before moving to comprehension fails to capture the intricate decision-making and metacognitive processes that even novice readers engage in. Real reading, from the very beginning, involves complex interactions between visual information (letters and patterns), tacit grammatical knowledge (how words function together), and intentional meaning-making (what makes sense in context).

When a child encounters "tears in his eyes and tears in his coat," they must navigate homographs that sound different based on context. When they read "The bat flew through the night," they must disambiguate between multiple meanings despite identical spellings and sounds. These linguistic complexities cannot be resolved through phonics expertise alone. Even beginning readers bring their knowledge of language and meaning to the task, and our instruction should acknowledge and build upon these resources rather than artificially separating them.

A more complete model of reading recognizes that while decoding is foundational, readers simultaneously draw upon multiple cueing systems in a recursive process. Phonics provides critical tools for word identification, but the goal of reading has always been comprehension. Our instruction should reflect this reality from day one, integrating phonics within a broader framework that values meaning and cultivates the mindset that reading is ultimately about making sense of text.

The most effective approach may not be choosing between phonics-first or three-cueing models, but thoughtfully integrating their strengths under the guidance of knowledgeable teachers who can assess individual needs and have the professional prerogative to adjust instruction accordingly. What matters most is not the purity of our theoretical models, but how well our teaching prepares children to become confident, flexible readers who can navigate the full complexity of written language.