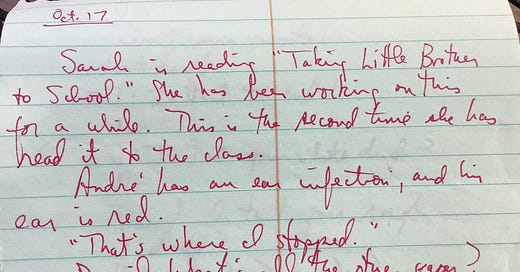

Sarah sits in front of her class on a stool in my memory. She wears a pink dress and patent leather shoes. When she smiles, her eyes sparkle. She’d asked me to save a time slot for her to take the Author’s Chair. I’m observing from a desk at the back of the room as usual during the closing fifteen minutes of writing workshop.

She had worked pretty hard on her essay, a memoir she provisionally titled “Taking Little Brother to School.” It had taken at least six weeks to establish workshop routines, and Sarah had been a big help in embedding by modeling the activities firmly in classroom culture.

This is just the way we do it. Everybody writes. Nobody skates. Teaching the class to use a working portfolio for a writing resource was trial by fire. I could write a chapter about the system I used relying heavily on Donald Graves and Nancy Atwell. A self-generated list of potential topics discussed regularly in teacher conferences was the lynchpin.

September flew by, and by October 17, Sarah—along with Brent, Laura, Mina, and several others, oh yes, Beth—was ready, to try out her draft seeking feedback from the entire class, to lead the class toward making the community work.

Daniel, a good-natured kid from a nearby farm, was a wee bit quirky—quick to smile, but not always attentive. His question was legit. “What’s all the other paper?” My observations were centered on instances of students’ using words from the workshop to talk about writing. I’d announced my stenographer’s intent and shared notes in mini-lessons to let them know I was interested in their work and how they talked about it. My bet is Daniel was testing Sarah; both knew I was writing in my steno pad at the time.

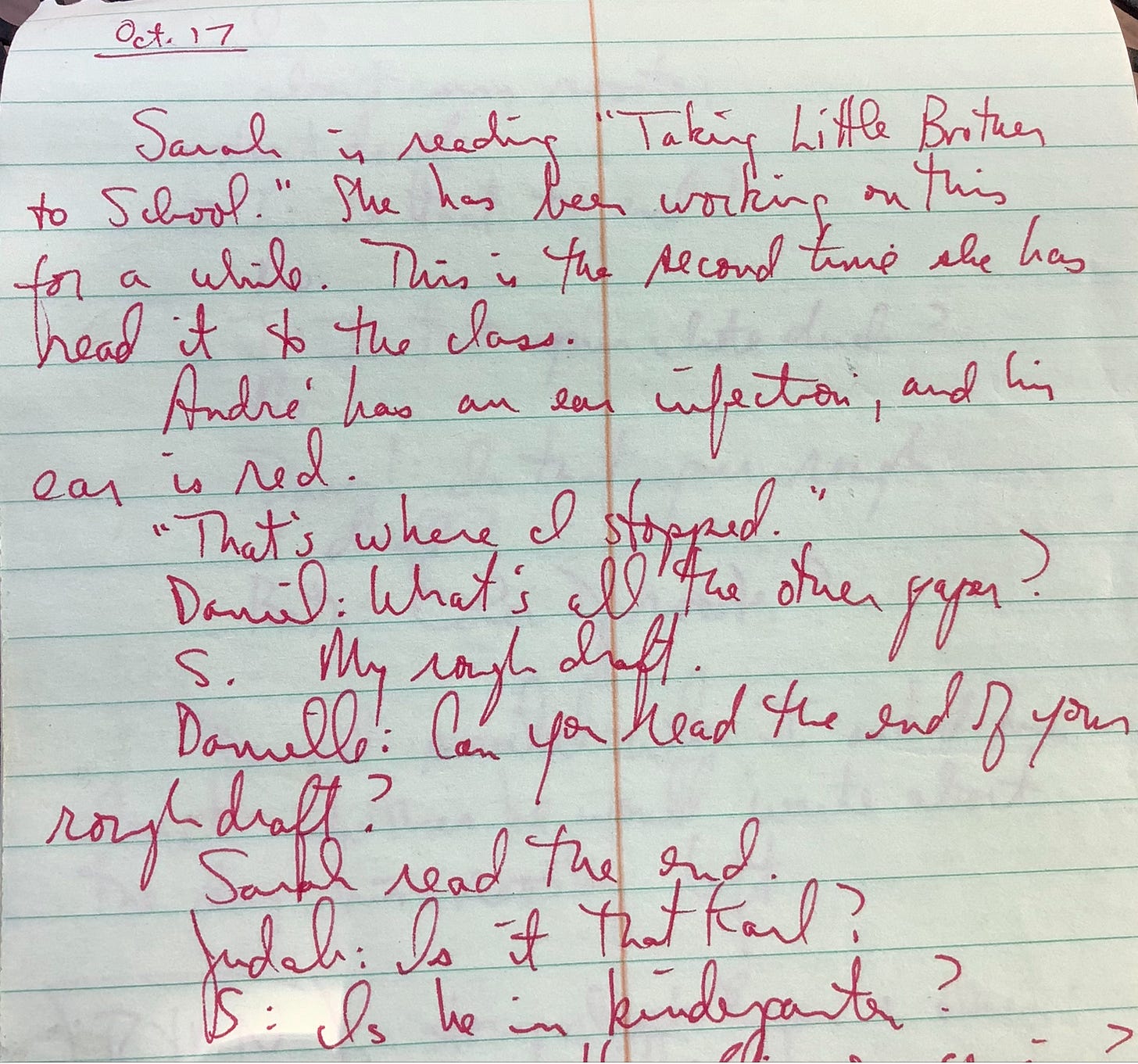

Danielle is crafty. “Can you read the end of your rough draft?” She does two things with her question. First, she revoices the words she knows I’m waiting to hear. She’s also aware that by doing so, she is earning brownie points, and she aligns herself with other students who have enrolled themselves in the community as bona fide writers. Frank Smith knew something after all.

Second, she knew that Sarah had been having trouble with the ending. Sarah’s mother missed out on Carl’s first day of kindergarten and suggested to Sarah, who escorted the little tyke to kindergarten, that she write a memoir for the family. I knew that Sarah had consulted with Danielle about the memoir from workshop records.

Peer conferences were impacted by limited space and quiet writing time. The first fifteen minutes of the period were mine, sixty minutes was for quiet writing, the last was Authors Chair. I had space for two small conference areas, which could be reserved or taken if not in use.

Documentation for a formal peer consult came with details—purpose of the session, questions for feedback, feedback received, outcome. There were quiet movements and brief consults routinely and spontaneously, but sessions ten to fifteen minutes long needed planning and my input. Sometimes I attended—as an observer.

I read these documents with great interest and talked one-on-one about them. These documents accumulated in a storage portfolio. Even more importantly, they opened the doors to direct teaching of a type of reading I called “reading a rough draft” or “reading and talking like a writer.” After Atwell I asked students to help one another with problems or to be thought partners looking for opportunities in a draft.

I chuckle when I think of Judah. A tall, lanky guy, this kid was an overgrown kindergartner, the kind of kid others were drawn to. “Is it that Karl?” You’ve surmised Sarah’s young brother is ‘Carl.’ Judah understood his quip. My Karl, my fourth grader, was a young intellectual, a scientist whose approach to writing mesmerized me all year. Karl in kindergarten? Really, Judah?

Sarah’s response came in an ambiguous package, though I didn’t and don’t believe she intended any insult to Karl, who may have been daydreaming at the time. “Is he in kindergarten?” On one level, the question is ridiculous. On another, Karl is ridiculous. The strategy of creating fictional avatars to represent student writers in the workshop crept into the classroom and almost destroyed the workshop, later in the year.

I didn’t see it coming.

*****

That year I taught and modeled psychological tools I thought might scaffold insights into how to shape a finished text from an early intention. Working with a topic occupied them at first. They had zero experience in this part of writing. Writing a working title, finding a purpose, zooming in on a project, drafting strategies, writing between the lines, zero indent (find paragraphs later), reading a rough draft for coherence, reading a draft to value content, reading to raise questions, cut cut cut, rearrange, fill in, replace, the right words in the right places, manicuring the text…

Sometime before winter break or thereabouts, a fifth grade teacher who had bought into writing workshop with me came into my classroom after school with a question: “Why are they writing all of these ‘fat boy’ stories in my class?” The chickens were coming home to roost. I’d been struggling more and more to stop the escalation of similar types of stories in my workshop:

A boy in the fifth grade class we shall call John was indeed very tall and heavy. A school counselor had been working with John to help him make friends with his peers. One afternoon she had John bake chocolate chip cookies in an oven in the cafeteria. She managed to get a parent volunteer to sew a costume for John, who was to emulate the Pillsbury dough boy and share the cookies. Very soon fat boy stories proliferated in my colleague’s classroom, and I was responsible for rubbing the genie’s lamp.

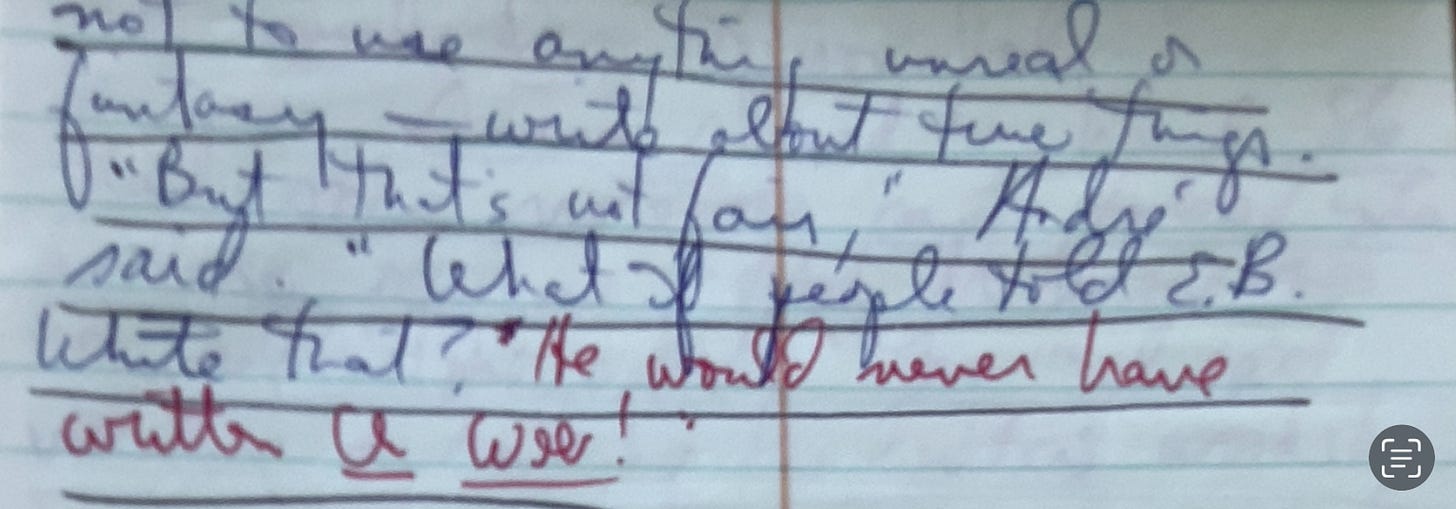

Without a doubt we had to take collective action. Our solution was to outlaw any references by name or innuendo to any student. I went so far as to outlaw fiction. Of course, I relented after negotiations with my students. Stupid huh? I’m constantly reminded of this experience whenever I hear about ban the bot campaigns. Andre, a kid with an infected ear, set me straight. Is it better to have loved and lost or never loved at all? Andre summed it all up in his comment about what the world would have lost if Mr. Underwood were in charge:

*****

Timothy Lensmire published a book on writing workshops in 1994 titled When Children Write: Critical Re-visions of the Writing Workshop which I didn’t read until the late 1990s. Adopting a critical perspective, Lensmire presents a compelling portrait of the real social and psychological dangers in looking at writing instruction from an idealized or romantic view on managing choice and voice in formal schools. Nowadays, I’m equally worried about heavy learning losses from looking at writing instruction from a meritocratic view on writing as argument and evidence—opinions in kindergarten.

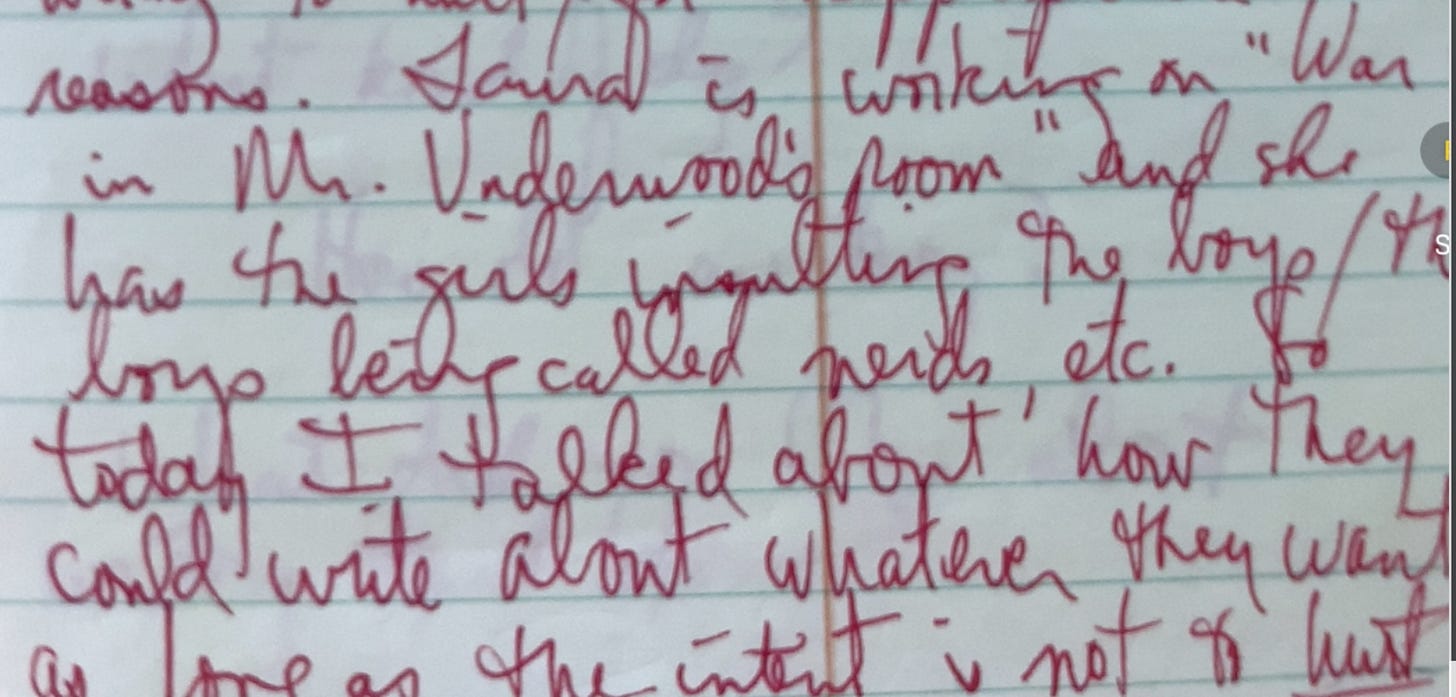

It seems obvious now. Writing isn’t just about audience and publishing. Social relationships and power dynamics among students affect the writing process and workshop interactions. Gender plays a role in students' writing choices and peer interactions within the workshop in hidden ways. We realized haphazardly that the boys were writing the fat boy stories. After I shut down the writing of fiction and any mention or oblique reference to any child at the school, Laura devised a way to walk up to the line by writing about abstract boys and girls in War in Mr. Underwood’s class.

The complexities of the teacher's position in facilitating a writing workshop are almost overwhelming. If I could step into Doc Brown’s Delorean, I would think much more about writer ownership for sure, but also a writer’s responsibility, before I tackled it. I try to assuage my sense of guilt for this unabashed failure by hoping that my kids someday understood why I had to stop the madness and restrict their choices. One of them, I know, went on to become an English teacher and told a reporter her interest in teaching writing was sparked in fourth grade by this teacher named Mr. Underwood.

.

These are really inspiring readings for anyone thinking about a possible job or experience where you would be teaching, explaining something or interacting with students. Thank you so much Terry for sharing. Your shared experiences are invaluable.

You bring up great points (and questions) here about the social dynamic at play in writing workshops. In my own adult classes, I’ve found that peer feedback is a crucial component, but only done in small groups that shift every few weeks. Anyway, I’d like to talk to you about this more 😉