Knowledge Planting, Watering, and Harvesting

“…[P]arenting…is especially important in species that have long lifespans, slow pace of development and large brains, like humans and great apes, as they have extended periods of juvenility, and maternal investment is crucial to increase infants’ fitness. In turn, these conditions provide extended opportunities for social learning, and also for the acquisition of socio-cognitive and emotional skills that are fundamental for complex cognitive processes (e.g. theory of mind; see [10] and [1], for reviews)” (Amici et al., March 6, 2023).

The first knowledge building tool in infancy is the human body. Infant fingers touch the world and learn to feel hot and cold, uncovering meaning to build durable knowledge required later to comprehend the concept ‘temperature,’ an epistemological feat denied by biology to, say, porcupines, who as mature adults know nothing of air conditioning or snow skiing.

Reaching for toys, infants learn to perceive and judge distance, speed, and depth of objects. Visual-motor coordination begins within days to weeks as they learn the value in turning their head to see the splash of red that flashed on the tv screen. Soon, they follow moving objects with their eyes on the way to depending on their eyes to guide their reaching. Before long some will be flying commercial airplanes, reaching for switches confounding to non-pilots. By six months, they are eyeing their hands, mystical appendages some will use to make music, the nectar of the gods, non-doable by non-musicians.

The ears of infants are precocious. Although sounds are muffled, human ear technology responds to sound waves in the womb. After taking center stage, stars in the drama of human life, they react to sounds, particularly loud sounds, though they can’t locate sound sources. After a month or so, infants recognize the voice of their primary caregiver, using muscles of the neck to turn their head. After several months, they understand the meaning of words like “bye-bye” and can coordinate its occurrence with a smile and a waving hand. They gurgle, babble, and coo. Most importantly, they love music.

To learn to walk, infants must at first crawl, of course, to develop strength in their leg and upper body muscles, their induction into Physical Education, but the body’s developmental curve doesn’t end there. Muscles in the neck fortify themselves to secure during perambulation the precious head, eyes, ears, nose, and mouth, each plugged into a brain, the apple of Apple’s eye, an executive toolkit unmatched by anything Microsoft could engineer.

Inside the skin, bones undergo a process called ossification, or hardening, gaining the physical properties of a portable, movable frame with sufficient structural integrity to sustain and help shape a body inventing itself. The vestibular system in the inner ear collaborates in a spurt of development with the nervous system, and infants learn to balance their mass in an upright posture, Homo sapien style.

The infant watches and sees, listens and hears, burbles, giggles, eats and spits, smiles and cries, building capacity as an infant epistemologist, knowledge building hour by hour, day by day. Interestingly, very recent research (Sun & Yoshida, 2022) highlights the importance of the parental gaze as a master tool of infant epistemology, a scaffold to train the infant to sync two separate sets of eyes laser like on a common object. It has been suggested that when a mature member of the species looks into the face of the infant and makes eye contact, the infant comes to comprehend their individuality, fostering a sense of self, me-ness, perhaps the deepest knowledge of all that jump starts the process of acculturation. Who am I in this place?

Amici et al. (2023) pointed out that gaze, however, like laughter and tears, functions differently in different societies. I’ve not come across the acronym they developed to refer to societies that oppress and dehumanize on a grand scale and would be interested in hearing from anyone who can locate wider use in the literature:

“…[F]ace-to-face interactions and mutual gazes are especially frequent in WEIRD societies (western, educated, industrialized, rich, democratic): mothers and infants often face each other, and engage in a variety of non-verbal means of communication, including facial expressions and eye contact (e.g. [18,29]). Through mutual gaze, mothers from WEIRD societies are thought to establish a communicative context with their infants, promoting the establishment of joint attention [30]. By contrast, face-to-face interactions and mutual gaze are often much scanter in other societies [14,15,31], where joint engagement may be expressed in other modalities, without the need to establish reciprocal visual contact [18].”

*****

In American society, the infant builds a sense of self—and a sense of what it means to know something—over five or six years in the bliss of toddlerhood when a remarkable rite of passage takes place. The child becomes a student in school. Crossing the threshold of the classroom means leaving behind a world known informally, sensually, and haphazardly systematic, and entering one with crisp lines formally outlining domains of knowledge organized according to public principles subject to knowledge ossification. The work of expanding knowledge shifts from self-centered to other-centered control with increasing demands for self-subjugation. Growing up, perhaps? Perhaps the hint of this shift is behind the tears children sometimes cry as the first day of kindergarten approaches.

From a layperson’s perspective, the perspective you might get if you asked ChatGPT3.5 or did a Google search, kindergarten is where children learn letters, sounds, and a handful of words, enough to write a simple sentence. They learn to count by 1s, 2s, 5s, and 10s; to use the operations of addition and subtraction; and to identify shapes by name. All of these learnings accumulate as learner gain expertise in foundational reading and math skills. In the domain of reading instruction, the conventional wisdom puts a wall between kindergarten and first grade. Phonics instruction commences in earnest in first grade.

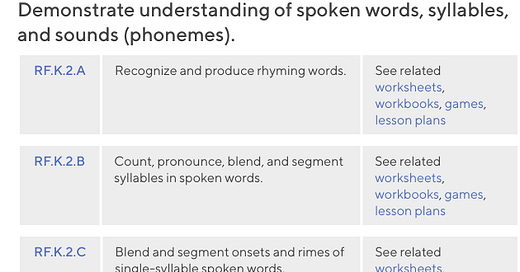

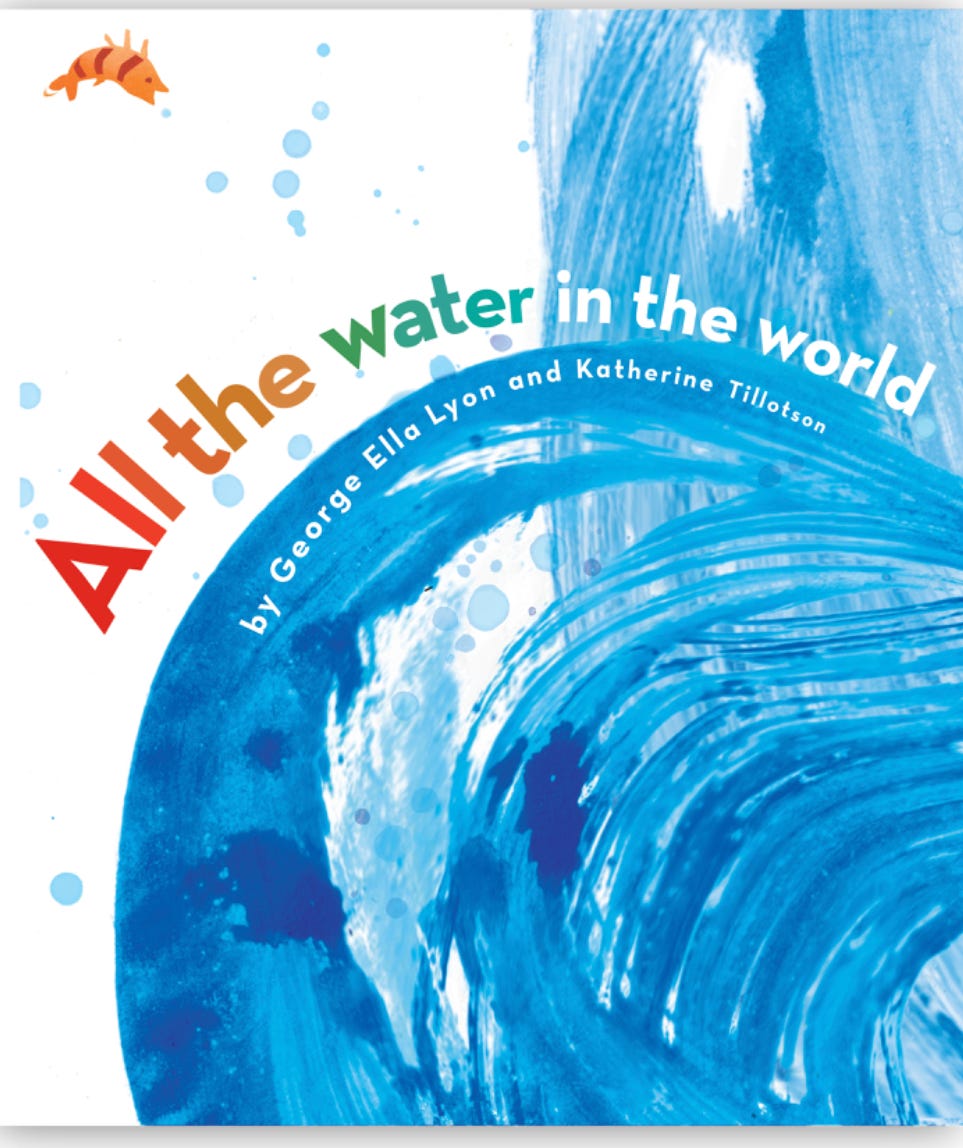

The Common Core State Standards for Kindergarten English-Language Arts paint a different picture. Aligned with solid research studies implicating phonological awareness, a linguistic metacognitive skill, in the chain of capacities leading to reading fluency, for example, these standards call for learners to become proficient in segmenting spoken words into syllables and phonemes and manipulating them:

Imagine an Orwellian society in which some children are restricted from learning to read while others are expected to read at highly competent levels. In such a society teaching a conversational child restricted from reading to isolate the initial, medial vowel, and final sounds would be a colossal waste of time. The child has already built knowledge of the phonological subsystem of the language. Additional instruction in analysis of that subsystem is needed only for children destined to read. Of course, to thicken the plot we have to deal those thousands of children who develop metalinguistic competence through their solitary or shared playing with words during toddlerhood. Some children simply learn to read, no muss, no fuss.

Kindergarten in the age of the Common Core has upped the ante for toddlers-in-transition in another research-based way as well: Students are expected to learn from informational texts. Such texts are non-fiction and stimulate the beginning stages of the academic epistemology so highly valued in WEIRD societies, that is to say, they start to crawl on the path to college and career, they cross another threshold into six years of general education at which time the curriculum fractures into disciplines defined by discreet funds of knowledge. Witness:

The first standard, asking and answering questions about information whether presented through silent reading or a read-aloud, is perfect from the standpoint of knowledge building. In the past, the emphasis was on teaching students to answer questions, not to ask questions. Having a question invites knowledge building. Of course, as time passes, students need to learn to answer questions others have for them, including their teachers, building even more knowledge. The final standard, comparing and contrasting two texts on the same topic is equally perfect as a starting point.

Notice that all of these informational text standards are instrumental, that is, they are a means to an end. The standard itself is the object of instruction, the teaching of how comprehension is achieved. Said differently, what teachers who enact the standards aim for is to see students who ask and answer questions, who identify topics and key details, who separate the separate contributions of the author and the illustrator. What is missing from these standards?

The outcome of the reading—the knowledge itself, which is not a property of the text but of the learner.

*****

The Knowledge Building Review tool I’ve discussed in the past two ltRRtl posts sharpens the focus of these informational reading standards in profound and promising ways. In view of the reality that reading informational texts has one primary goal, to build knowledge from the information, we miss an opportunity when we allocate pedagogy to the informational reading process but are silent about building specific content knowledge.

What’s more, the relationship between content knowledge and reading comprehension is complex, difficult to disentangle, implicating everything from personal interest and prior experience to domain-specific vocabulary and conceptual development. The quality of the learning how to comprehend and explain details about a topic gleaned from a read-aloud in kindergarten depends on the topic and the details a learner already knows. Not dealing with content in a forward-looking way can influence the quality of the kindergarten experience and the level of success students have when reliance on reading comprehension as a primary tool of epistemic growth comes into play when the curriculum breaks apart and GPA becomes a determining fact of life. From the Knowledge Campaign Review Tool:

“Throughout this document, we have used the phrase ‘content knowledge’ over ‘background knowledge’ whenever possible. While recognizing that ‘background knowledge’ is the more familiar term, we seek to underscore that curricula rich enough to support reading comprehension will focus not just on any knowledge, but specifically on important science, history, civics, geography, arts, and literary knowledge.”

By stipulating a definition of knowledge congruent with the tradition of disciplinary knowledge building in public schools, the review tool does not seek to upset the apple cart, but to work within the reality principle. By centering on the significance of content knowledge and academic language as the backbone of reading comprehension in the disciplines (rather than general fluency and vocabulary), the review tool seeks to backfill a conspicuous hole in the traditional elementary school curriculum primarily by making some minor pedagogical adjustments coupled with a topical elaboration in the local curriculum.

*****

[This is a fictional narrative intended to clarify a vision of application of the Knowledge Matters Review Tool.]

Mrs. Wren, a first grade teacher, is planning to do a read aloud about the content topic “water” as part of a curricular unit on fact and fiction. This topic, water, was established in the local curriculum as a focal topic for K-2 under natural science in K, geography in grade 1, and history in grade 2. Grades 3-6 fold content knowledge built during K-2 into intermediate teachers’ work when readers draw on this knowledge as they comprehend and learn from texts about a broad organizer ‘agriculture in history.’

Her specific water knowledge building lesson objective is twofold: First, she wants to support the children in knowledge building about the concept water by engaging them in analysis of what they think they know to be factual about water. As part of this lesson, she wants to reinforce earlier lessons focused on supporting students in building a schema for identifying differences between fact and opinion, fact and fiction, non-fiction and fiction, a topic taken up again in first and second grade. The earlier grade levels are responsible for introducing, practicing, and independently using this schema in reading and writing. All of the teachers across the school have a shared understanding of this umbrella outcome as well as an inventory of basic, predictable lesson designs and shared pedagogical strategies.

In the literature portion of the English-Language Arts period, she used some poems about water to provide experiences in imaginative expressions of the meaning of water. "The Duck and the Kangaroo" by Edward Lear is a humorous and imaginative story-poem about water as the preferred environment of the duck. Children had the opportunity to make up a creature that floated on water and write about it. "Rain" by Robert Louis Stevenson from 'A Child's Garden of Verses' explores the theme of water in the form of rain. Children brainstormed the many forms water can take and explored the idea of shape-shifting, writing about an imaginative substance that shape-shifts. "Wynken, Blynken, and Nod" by Eugene Field uses the ocean and a boat as metaphors to represent a dreamlike trip to the stars. Children explored the idea of the imagination as a kind of shape-shifting tool, explored the concept of a metaphor, and discussed how things would change if suddenly there was no imagination.

For the fact-based lesson she plans to lead a Socratic discussion of sorts to draw out facts and misconceptions the learners may harbor about water as a physical substance. She decides to take a water bottle with her to her stool at the front of the classroom. She uses furniture in the room to reinforce the nature of the activity. During knowledge building sessions, students form rows of desks. During literature sessions, more informal though quite well-managed formations appear.

Why do people and animals drink water? she plans to ask and then she will take a sip of water. She expects statements like "Water stops us from feeling thirsty” and plans to follow up with the question “Why do you think the body tells us to drink water?” Another question will be “Why do plants need water?” with follow ups like “What happens when plants don’t get enough water?” She expects responses like “Plants need water to grow flowers” and “Plants need water to make vegetables.” An important follow up will be “Is it right to say that plants drink water?” Her final question will be “Why do living things need water?” and “Do you know for a fact whether dinosaurs drank water?” She will proceed to do a read-aloud.

I found two non-fiction books online that appear to be suitable to use in this situation. I can’t vouch for whether they are appropriate and factual, but it appears as though books on factual topics are available in the marketplace. I’ve read about a big need for vetted nonfiction books to serve pedagogy in the early and even later elementary grades, but to the degree that a perspective like that of the Knowledge Building Campaign finds legs, commercial publishers as well as educators themselves should have the capacity to produce high-quality materials.