Building Community One Student at a Time

Charles Ruff’s second period English class is in rare form, laughing, carrying on friendships old and new, as they cross the threshold, and to their seats they scatter before the tardy bell.

His students behave as if they’d been friends for months, not a matter of days, more evidence of the sophomore effect, Harold’s term. Harold has a habit of captioning everything. He thinks this predictable camaraderie is designed by the academic counselors, who do after all call the curricular shots during the first year at MidWest Public Prep.

Building community one student at a time, one year at a time.

It takes him a minute to get them to quiet down. He begins talking quietly, and they focus on his hocus pocus (Harold again).

Psychological Tools and Joint Attention

“I learned to use psychological tools when I was in high school from a very special teacher,” Charles says.

He waits. Think time, he thinks.

“Go on,” says Max. “What about these tools? What did you call them—psychological tools? What, so you could tune yourself up if you started passing gas in public places?”

“Thanks for asking, Max. All bets are off in this race.”

“Sorry,” Max says, “I couldn’t resist.”

“Well, in a strange way, you are absolutely right—that’s if by passing gas you were to mean blathering on like a fool about nothing in particular, speaking as it were hot air. In that scenario, one could put a few psychological tools to good purpose.”

An array of happy faces lifted his spirit. They were beginning to listen to one another.

Joint Attention and Bots

“I don’t know where to start,” Charles says. “Well, let’s begin at the beginning. What do you think?”

“About what?” someone says.

“Isn’t it obvious?” asks Charles. Then quickly: “Can you hear me?”

“What was that about passing gas? that hot air scenario?” says Christine. “Mr. Ruff, are you passing gas right now? You’re doing this on purpose!”

“Yes, I think I am.”

“I have a psychological tool I can let you borrow,” says Max.

“I think I already have my own,” says Charles. “I call it my ‘joint attention’ tool. I use it very deliberately when I’m writing, when I want to bring your attention to what I am paying attention to. If all I wrote about was what I’m paying attention to without regard to bringing you along with me, I wouldn’t need my joint attention psychological tool.

“But we have opportunities to use it every day. It’s an excellent tool to raise your skill level in using a bot. In fact, I see in recent self-assessment reflections that you are getting your feet wet with language bots. Some of you find it useful when you are reading, and I want to help you with that. It would help me if you would write more specifically about your uses, but we’ll talk about that later.”

“Could we talk a little about it now?” Kyrie asks. “The reason I ask is sometimes that bot ain’t paying me no attention. It says what IT wants to say.”

“Yeah, and even then, sometimes it’s not going to answer you,” someone says.

“Teachable moments,” smiles Max.

“Kyrie, you are so right. Thank you for bringing this to my attention. Do you see what Kyrie did? He used his joint attention tool to get my attention to focus on why it’s hard to get the bot to pay attention to you. The bot and the joint attention problem. How do we use the bot to get back from it exactly what we need? This has already helped me.”

Garbage In, Garbage Out

“How do human beings establish joint attention? How do we know when we are together that we are paying attention to the same thing? Let’s say we are walking through a park with a friend and your friend says ‘Look!’ How do you know where to turn your eyes?”

“They could be pointing their finger,” someone says.

“You could see where their eyes are staring,” someone else says.

“You could figure it out. I mean, you’re in a park. It’s obviously something you wouldn’t expect to be in a park,” a third someone says.

“Maybe we were walking through the park looking for a stolen bicycle and—voila—there it is,” a fourth chimes in.

“Maybe we had heard a dog barking and all of a sudden the dog comes out of some trees,” says a fifth.

“So Isaac would look for a gesture like a finger pointing, Sarah would look at her friend’s eyes, Randall would look at the whole situation, Kyrie would look to a shared understanding of intention, and Cecilia would combine noises with images . But each of you would achieve joint attention correct?”

Bots and Self-Attention

“Let’s try a thought experiment. You’re in the same park, your friend says ‘Look!’ But this time your friend has no body, no eyes, no ears. Your friend has no memory of you. This friend doesn’t know that you were looking for a bicycle, that you are even in a park. Your friend knows nothing but what you write in a note or say into a recorder. Sound familiar? How do you establish joint attention when you are walking through a park with ChatGPT?

“In fact, joint attention tools are exclusively human. Bots exist for one sole purpose: To determine what the user is paying attention to and adopt it. Humans and bots do not pay joint attention. When humans communicate with a bot, humans are paying attention to ideas, they may assume the bot is trying to pay joint attention, but bots do not have the capability to pay; bots take directions. People expert in computer science describe the bot’s attention capacity as ‘self-attention.’

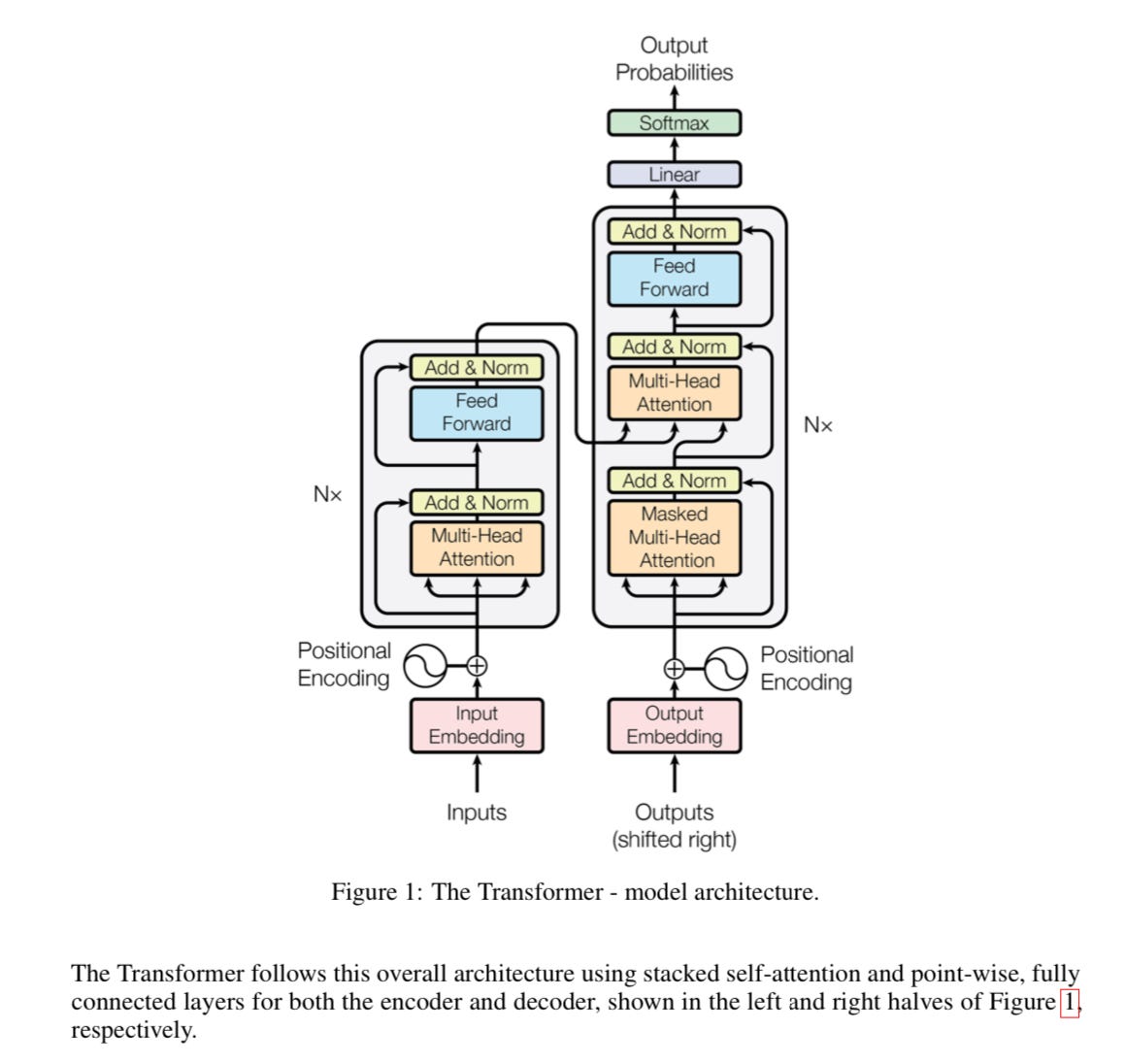

“I want to focus our joint attention on a figure I’ve excerpted from a scientific article titled ‘Attention Is All You Need.’ This use of the word ‘attention’ is ambiguous; the authors aren’t referring to human attention, but to attention mechanisms designed into the bot’s transformer:

“LLMs have two layers, on the left an input layer, which is whatever you type into the bot, on the right is an output layer, whatever the bot supplies you with. The input layer has one task: to figure out what the user is paying attention to, what the user is searching for. A human uses words to describe a situation, and those words are converted to numbers which are added and normalized and sent to the second layer, the output layer.

“In the human-human, I-You, condition, the user’s words would interact with another user. They would share a common focus, a joint attention. There is an authentic meeting of minds. In the human-AI condition, I-It, the bot has no intuitions, no shared experiences. If it pays attention, it pays attention to itself, working to dig up strings of words that are statistically likely to meet your expectations.

“I tell you this in order to give you the first principle of Bot User Guidance: The bot is not capable of paying attention to anything except for the words the user inputs in layer one. It divides and subdivides, it calculates probabilities, but it cannot attend to anything beyond its input. We’ll simplify this principle to one we already know. Garbage in, garbage out.”

Avoiding Garbage In, Garbage Out

“Here’s one example. Imagine someone is reading an assignment on meiosis in a biology textbook. Does anyone happen to know anything about it?”

A few shaky hands are raised.

“The section has the word ‘meiosis’ in the title. Like any astute and effective reader of complex scientific texts, this reader skims the assignment, looking for cues linking the subsections to the term ‘meiosis.’ It’s clear the passage was written to focus your attention on this concept, not on its definition. The job is to understand a concept, not to recall unrelated definitions of words. Remember a text written by a human represents a human focus of attention, and your textbook in this case was not written by a bot—not yet anyway.

“Here’s a scenario. Imagine yourself preparing to do some homework. You’re finding biology pretty interesting, especially this unit on cells. Your teacher expects you to come to class with a good understanding of meiosis so you can participate in a simulation. You are here. The passage is here. Here is the bot. Find three other people who will talk with you. Come up with at least four different specific ways you might decide to use the bot productively to avoid garbage in, garbage out, knowing what you know about the bot’s self-attention mechanism, human joint attention, how the two layers of LLM transformers work, and your purposes in reading the assignment.”

“I don’t understand the directions,” someone says. “This is all new to me.”

“Ok,” says Charles. “It’s new to me as well. Let me try this another way. In the scenario, the student and the biology teacher are paying joint attention to an assignment. The teacher asks you to prepare yourself for a simulation. Garbage in to a bot comes from the human, and garbage out comes from the bot. Create four ways to avoid putting garbage in. You will be searching for ways for the rest of your lives. We all have to start somewhere.”

“Can you give us a few examples?”

“All right, all right, if you insist. You might be tempted to turn to bot and ask something like ‘Tell me about meiosis.’ What is the bot trying to do? Locate your focus of attention and adopt it through using self-attention mechanisms. It’s trying to pretend it has your focus. Well, tell me about meiosis—are you sure you are giving the bot sufficient directions to do some artificial thinking on your behalf?

How about this: ‘I have an assignment to read six pages about meiosis for my biology class tomorrow. I’ve heard of it before, but I don’t know much about it. I intend to read the assignment carefully and take notes. I have to understand it thoroughly so I can participate in a simulation tomorrow. Can you test me on my knowledge of meiosis? That could help me figure out what I already know but can’t quite remember.’”

“Clever,” Max says. “I like it. Let’s get busy, Isaac. We need two more peoples over here.”