Inner Speech: A Coda

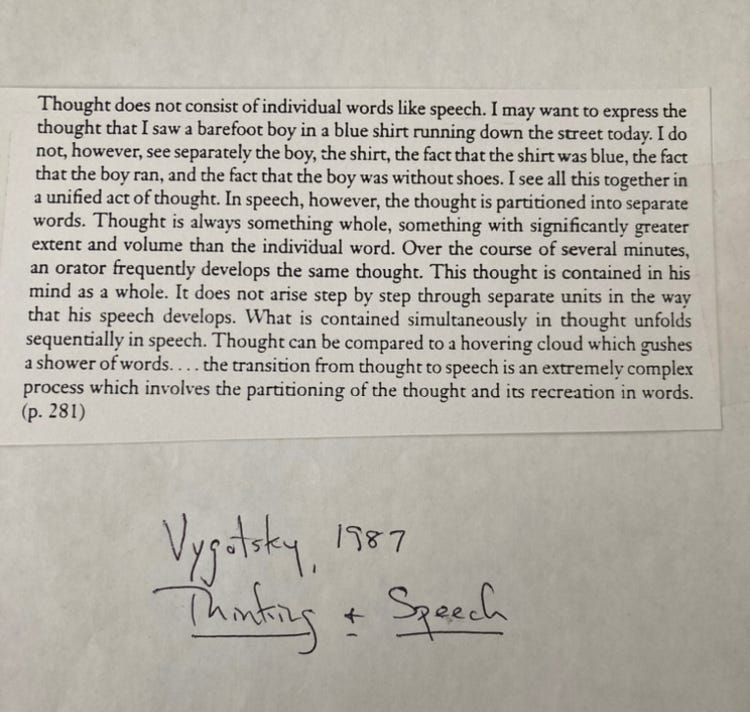

Today I’m offering a photo of a paper master copy I used to make an overhead transparency of a quote from Vygotsky’s masterpiece titled Thought and Language. I showed the transparency in my classes.

As a tool for time binding, language written in the distant past across the world in a foreign language can fuel cognition today at the event level just as powerfully as it did in my content area reading sections when I displayed it on a screen.

The difference between us now and us then is this: We then discussed immediately the implications arising from Vygotsky’s insight.

“Thought does not consist of individual words like speech,” Vygotsky begins. If reading comprehension is a thought process defined by the exigencies of print, by modus ponens reading comprehension does not consist of individual words added linearly.

Speech transforms from the affordances of the physics of orality during communication events that focus joint attention to a freewheeling concatenation of semantic particles during cognition.

Reading is not the same as listening. The simple view crumbles into flakes. By the same token, writing is not the same as reading. Writing requires partitioning into words just as speaking does. Reading requires de-partitioning words.

The idea that reading comprehension is the result of reading aloud to ourselves in our head as the pathway to cognition, that we have to build reading comprehension painstakingly word by word, phoneme by phoneme, is inadequate to explain our subjective experience as thinkers comprehending texts of all sorts and genres.

Can you visualize a barefoot boy in a blue shirt running down the road a century ago somewhere in Russia? You no doubt see him in a unified act of thought as Vygotsky writes. Did you convert any word to speech?

What if the barefoot boy were a country, the running down the street were Wall Street, the blue shirt were green—how would your thought process best be characterized as a result of more abstract, more complex metaphorical demands on content?

As verbal thought becomes thicker in the sense of meaning, more dense, you slow down a bit, but do you speak the words to yourself? Perhaps if you are profoundly confused or moved…

“Over the course of several minutes, an orator frequently develops the same thought,” Vygotsky continues. “This thought is contained in his mind as a whole.” It is only when the orator switches from inner speech to outer speech that words must be apprehended one at a time. The medium change changes the relationship with cognition.

Isn’t reading fundamentally different from listening? Doesn’t separating the message from the auditory channel change the relationship between thought and speech? Doesn’t reading remove constraints of joint attention by holding the message stable, time-bound?