Inequality, Part 5: From Segregation to Integration to Resegregation

John Roberts Needs New Glasses

Part One discussed how the U.S. federal government crafted New Deal legislation to create residential segregation in the early and mid 20th century leading to persistent school segregation.

Part Two established the differential consequences of New Deal policies regarding home ownership leading to intergenerational inequity.

Part Three showed how White privilege and Black exclusion produced a wealth gap that brought about a systematic learning gap.

Part Four developed the social and political structures that sustain U.S. public schools by way of analogy to a three-legged stool (local school boards, state governments, the the federal government).

Part 5

SUMMARY: This essay traces a historical arc from the 1954 Brown decision through the peak of integration in 1988 to the resegregation that followed, revealing both the legal architecture that enabled progress and the judicial reasoning that dismantled it.

The analysis moves backward to recover the intellectual origins of Brown in W.E.B. Du Bois and the founding of the NAACP. It then moves forward through the violence and chaos of the struggle for a remedy, through the hard work of the busing era, to the folly of Chief Justice John Roberts's false symmetry of colorblindness.

Empirical research on the contact hypothesis and longitudinal studies of integration's effects on adult outcomes establish what desegregation actually accomplished. A theoretical framework of the mechanism of White supremacy follows, drawing on Fanon's White gaze, Joyce King's dysconsciousness, and Flores and Rosa's raciolinguistic ideologies to explain why integration worked and how its absence reproduces inequality through the ears of the White listening subject.

The essay concludes by examining how large language models automate and scale that same perceptual structure.

Marking Time

If 1954 marks the beginning of desegregation and integration, 1988 marks the peak of its impact across the country, but particularly in Southern public schools. In 1988, the percentage of Black students attending majority White schools reached roughly 44%. In 2007 conservative politicians and judicial activists regrouped and ushered in a false consciousness of success and the terrible swift irony of No Child Left Behind. In 2025 the country’s legislative emphasis has shifted from intergenerational redress of inequality to explicit, systematic phonics.

Pathological Resistance to Integration

The collective will to integrate public school in 20th century U.S. caused seismic society-wide tremors immediately in 1954, but damages from these tremors to physical and social and emotional health spread decade by decade. Brown didn’t stop the Ku Klux Klan from riding on its night missions, the same missions it carried out during Reconstruction and Jim Crow.

In the 1920s, the “second” Ku Klux Klan was a mass, nationwide movement of White Protestant Americans that blended fraternal-club culture, electoral politics, and White supremacist nativism with night‑riding terror in the South. It claimed millions of members, operated openly, and portrayed itself as a defender of “100% Americanism,” Protestant morality, and law and order while targeting Black people, immigrants, Catholics, Jews, and perceived moral “degenerates.”

The “second” Klan declined by the 1940s, its national organization fractured, but a loose network of local Klans and sympathizers persisted, especially in the Deep South. Black hangings and church bombings outraged much of the country, and nonviolent sit‑ins and protests at lunch counters, libraries, theaters, and other public spaces in the 1960s, helped push integration in public spaces forward.

A new “third” Klan surged in the 1950s specifically in response to Brown v. Board of Education, the end of legal school segregation, and broader civil rights gains. Klan leaders framed desegregation as a threat to “states’ rights,” “law and order,” and “White civilization,” and sought to stop Black political, educational, and economic advancement.

Klan groups used bombings, arson, beatings, and murders to terrorize Black families, civil rights workers, and White allies with Blacks. On September 15, 1963, a bomb planted under the steps of Birmingham’s 16th Street Baptist Church killed four Black girls and injured many others. On June 21, 1964, civil rights workers James Chaney, a Black Mississippian, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner, two White New Yorkers, were abducted and murdered in Neshoba County, Mississippi. The killings were planned and carried out by local members of the White Knights of the Ku Klux Klan, with assistance from local law enforcement, in retaliation for their voter registration work and investigation of a burned Black church.

Kingdon et al. (2024) researched the Klan’s migration to digital platforms and exposed a rhetorical challenge facing White supremacists. How does one mark Whiteness when its ideological power has historically derived from remaining the unmarked norm? Kingdon et al.’s analysis reveals that “terminology related to [W]hiteness was a significant theme” across all twenty-six websites they studied through non-participant ethnography, yet “seemingly contradictory discourses and narratives about [W]hiteness co-exist within and across sites.” This incoherence reflects the structural difficulty of rendering explicit what White supremacy typically keeps hidden in the darkness of ignorance.

Some factions anchored Whiteness in Confederate heritage and American nationalism while others invoked broader framing like “the ideas and ideals of Western Christian Civilisation.” The simultaneous presence of local, regional, national, and transnational constructions of Whiteness, ranging from Pittsburgh demographic anxieties to South African farm murders, suggests not strategic flexibility but ideological instability. When Whiteness must be spoken rather than assumed, it fragments into competing scripts.

Kingdon et al. (2024) found a narrative of victimization, i.e., positioning White Americans as targets of “reverse racism,” replacement, and persecution. This rhetorical move attempts to re-mark Whiteness not as dominant but as endangered, swapping out structural position for grievance. The digital Klan thus reveals what happens when an ideology predicated on invisibility must make itself visible to recruit new ideologists.

Looking Backwards: The Roots of Brown

Somehow, the festering societal forces of racism and those afflicted by its advocates which spent the first two-thirds of the 20th century fighting against equity gave way in physical reality and now have a blossoming digital presence. The legacy of all the hard work U.S. citizens devoted to a whole-of-society effort to desegregate public schools is profound, if imperfect. White supremacy has proven to be like one of those weeds that resist elimination.

Moreover, the unsung work that went into producing the Supreme Court decision that made integration possible in 1954 is inspiring. There is so much more yet to do that depends upon knowing about the history of the struggle. To fully understand how deeply desegregation changed America despite its temporary setbacks today, it is essential to think about the origin of the NAACP and its link to W.E.B. Du Bois.

Du Bois’ Niagara Movement for civil rights, beginning in 1905, upped the ante on political organization among Black intellectuals as dissatisfaction with Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist perspective on Jim Crow segregation and Black disenfranchisement intensified.

Washington publicly urged Black Americans to accept segregation temporarily, avoid direct political agitation, and focus on industrial education, hard work, and economic self‑help, especially in his 1895 Atlanta Exposition address, later dubbed the “Atlanta Compromise.” He believed that being useful and reliable would gradually win White approval and lead to expanded rights over time. Historians have shown that he also secretly funded and supported specific legal challenges to segregation and disfranchisement, indicating a dual strategy of public moderation and behind‑the‑scenes opposition.

Du Bois insisted that Black progress required a liberal‑arts background and higher education for a leadership “Talented Tenth,” fostering intellectual development and critical thinking. He believed that about one in ten Black Americans, if given classical higher education, would become teachers, professionals, and intellectual leaders who could “lift” the broader community socially, politically, and morally. For Du Bois education was intrinsically tied to civic and political equality—to gain skills, but more importantly to produce citizens able to challenge White supremacy, analyze injustice, and reshape institutions.

Surviving records and later accounts document the July 11–14, 1905, gathering at the Erie Beach Hotel in Fort Erie, Ontario, where Du Bois and twenty‑nine other Black men drafted the Niagara Movement’s constitution and Declaration of Principles. [Here is an online archive of materials written by DuBois.]

Shortly after the declaration in the midst of widespread racial violence, the NAACP was founded on February 12, 1909, on the centennial of Abraham Lincoln’s birth. The 1908 Springfield, Illinois, race riot shocked many White progressives because it had occurred in Lincoln’s back yard near the granite monument where Lincoln, his wife, Mary Todd Lincoln, and three of their four sons are buried.

White men in mobs systematically targeted Black homes and businesses while sparing White property. Residents who fought back were brutally attacked or killed. Nearly 2,000 Black residents fled permanently. After three days, the militia restored order; of 150 arrested, few faced conviction.

This higher level of intellectual organization instigated by DuBois brought together two streams of thought. White progressives from the social reform movement joined Black thought leaders, including Du Bois, to plant the seeds for a future of reform, blossoming in the Brown complaint. Du Bois became the only Black officer in the initial NAACP leadership structure, serving as Director of Publicity and Research and editing The Crisis, which became the organization’s influential magazine.

The platform that came from the 1909 meeting of the Negro Action Committee began with the following language:

“We denounce the ever-growing oppression of our 10,000,000 colored fellow citizens as the greatest menace that threatens the country. Often plundered of their just share of the public funds, robbed of nearly all part in the government, segregated by common carriers, some murdered with impunity, and all treated with open contempt by officials, they are held in some States in practical slavery to the [W]hite community.”

The platform documented plunder, disenfranchisement, segregation, and murder, and noted that this persecution bore most heavily on poor White laborers whose economic position most resembled that of Black Americans. The NAACP called on Congress to strictly enforce the Constitution and the civil rights guaranteed under the Fourteenth Amendment. There should be equal educational opportunities for all. Public school expenditures should be the same for the Black and White child.

Du Bois grew increasingly skeptical in the 1930s and 1940s that simple legal integration, especially of schools, would mean justice. He worried that Black students would be “admitted but not welcomed” into hostile White institutions, receive an education “worse than pitiable,” and be subjected to racism, miseducation about Black history, and constant assaults on their dignity.

He also feared that desegregation would close many Black schools and displace “superior black teachers,” who, he argued, would not be hired in White‑run systems because “they will not and cannot teach what many [W]hite folks will long want taught,” a prediction borne out when tens of thousands of Black educators in the South lost their positions after Brown v. Board of Education. Gloria Ladson-Billings published a moving analysis of this cost in a chapter of Equity and Education Since Brown v. Board: Where Do We Go From Here? (Nasir and Darling-Hammond, 2025).

Other influential thinkers cherished the possibility of a positive link between integration and the production of better citizens. Children mixed together in classrooms could reduce levels of prejudice. This measurable effect is known as the “contact hypothesis,” a social-psychological theory articulated by Gordon Allport in 1954, who believed that, under the right conditions, social interaction between Black and White children could reduce prejudice and improve intergroup attitudes.

An insight that effective teachers learn quickly, everything hinges on the right conditions. Allport’s theory explained that prejudice-reducing contact requires a) equal status in the situation, b) cooperation, c) common goals, and d) clear support from authorities like teachers and principals. Without the right conditions, Du Bois’ doubt was compelling. How could integration ensure the right conditions?

Fortunately, Allport’s criteria guided the implementation of desegregation in many U.S. schools. As we will discuss in more depth later, NAEP trend data provide strong quantitative evidence that, during the main era of school desegregation, the Black–White achievement gap in reading and math shrank substantially, consistent with research on the benefits of integration. There is reason to believe that integration changed the hearts and minds of a generation.

After Brown I (1954) declared segregation unconstitutional without specifying remedies and Brown II (1955) offered only the vague mandate of “all deliberate speed,” using school buses to transport White children to formerly Black schools set off a maelstrom of White resistance through the 1950s and 1960s, postponing progress until the 1970s. Du Bois’ prediction seemed to come true in the 1960s.

What About Brown and Busing?

Busing for school desegregation, i.e., transporting students specifically to reduce racial segregation, began in the late 1950s and early 1960s in a few Northern districts. New York City is the official location of the first small-scale experiments. In 1961 the city arranged student transfers between predominantly White Yorkville and predominantly Black and Latino East Harlem.

During the 2019 Democratic presidential primary debates, you may remember, Kamala Harris described being one among the early cohorts of children bused across town in Berkeley, California. Berkeley launched the nation’s first voluntary two‑way busing plan in 1968. Black children in neighborhoods closer to sea level would be picked up and bused to schools in Berkeley’s affluent hills. White children in those hills would travel to new schools in the flats.

The yellow school bus has earned its place in American history as a symbol of hope and progress. It is inextricably linked to the story of integration in a country that had been founded on Black slavery.

The Road to Brown

Linda Brown from Topeka, Kansas, took a dangerous daily trek past White schools through busy intersections and across a rail yard to reach a bus to get to school, a designated all-Black school. In 1951, Topeka’s school board refused to enroll Linda, Oliver Brown’s daughter, in the all‑White elementary school just a few blocks from their home. The name Brown would forever be attached to desegregation as short hand for integration as a remedy. Nothing about this work was easy.

Briggs v. Elliott in South Carolina, the earliest of the eventual Brown cases, grew out of organizing in 1949. Harry Briggs and twenty others filed a complaint against the Board of Trustees of School District No. 22 in Clarendon County, South Carolina. Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense Fund argued that the school district discriminated against Black students by refusing them access to schools attended by White students.

After the complaint was filed in a district court, the home of a reverend, a driving force behind the suit, was burned to the ground. White firefighters refused to put out the flames, claiming it was outside their jurisdiction.

The Supreme Court first heard the consolidated Brown arguments in 1952 and decided the case in May 1954, so the set of related cases spans roughly five years from the first filing in 1950 to final decision in 1954 with groundwork beginning in 1949. According to a footnote in a Supreme Court document, Warren acknowledged that the consolidated cases arose from different states and local conditions but shared a common constitutional question.

The Justices were aware that Brown was breaking new Constitutional ground by overturning a precedent. The Court’s decision explicitly addressed the futility of looking to the original context of the 14th Amendment to determine whether it was designed to integrate public schools specifically. “Education of [W]hite children was largely in the hands of private groups…” at the conception of Amendment XIV, stated the formal decision. “Education of Negroes was almost nonexistent, and practically all of the race were illiterate. In fact, any education of Negroes was forbidden by law in some states.”

The Court also understood the import of the phrase “separate but equal” as used in Plessy v Ferguson (1896). The cases brought before the Justices in 1954 had been unsuccessful at the trial court level precisely because the 1896 precedent was found to be decisive. Even though the trial courts agreed that educational segregation had a negative effect on African-American children, it applied the standard of Plessy in finding that the White and African-American schools offered sufficiently equal quality of teachers, curricula, facilities, and transportation. The impoverished legal definition of equal began to collapse in the folds of the argument.

The legal journey from Plessy in 1896 to Brown in 1954 involves a crucial conceptual pivot from measuring equality through tangible factors to recognizing that segregation itself produces intangible harm that no material equalization can address. The key to understanding Warren's move lies in two 1950 higher education cases that laid the doctrinal groundwork.

In Sweatt v. Painter (1950), Texas had established a separate law school for Blacks. The case involved H. M. Sweatt, a Black postal worker who applied to the University of Texas School of Law in 1946 and was denied admission solely because of his race. Meanwhile, Oklahoma admitted a Black named McLaurin to graduate study. Once admitted, the university forced him to sit in a designated seat in a segregated row in class, use a special table in the library, and sit at a separate table in the cafeteria, State courts upheld segregation in both cases based on the Plessy precedent.

The Supreme Court ruled against segregation in these specific cases, not without uneasiness about leaving the separate but equal doctrine intact. Chief Justice Vinson emphasized the intangibles of legal education—faculty reputation, influential alumni, traditions, prestige, and, most significant for the doctrinal future, a student body including members of a race that would produce an overwhelming majority of the judges, lawyers, witnesses, and jury members Sweatt would encounter professionally. The Court explicitly turned to "those qualities which are incapable of objective measurement but which make for greatness in a law school.”

The 1950 ruling found that segregation within the classroom impaired a student’s ability to learn his profession. Together, these cases undermined Plessy’s tangible-factors test. Warren completed the work in Brown, declaring that separating children “solely because of their race generates a feeling of inferiority” that may never be undone. Separate was inherently unequal.

The doctrine had fallen—but implementation remained. Brown II’s 1955 instruction to proceed with “all deliberate speed” invited delay. Southern states mounted massive resistance. A full seventeen years would pass before the Court, in Swann, finally authorized the mechanism that would make integration real.

Southern Resistance

After the fact of Brown, the White South curdled in massive resistance. The 1954 decision defined the problem of American apartheid but articulated no remedy. In Brown II the following year, the Court reaffirmed that racial discrimination in public education is unconstitutional and held that all conflicting federal, state, or local laws must give way to Brown I. It instructed federal district courts to supervise desegregation, recognizing that local conditions varied and asserting that remedies would have to be worked out case by case, a recipe for molasses.

The Court directed school authorities to make a “prompt and reasonable start” toward compliance and to achieve desegregation “with all deliberate speed.” This standard acknowledged the breadth and depth of the change. It also allowed resistant states and districts to stall with all deliberate speed.

Historians argue that Brown II softened Brown I’s impact by legitimizing the dragging of White feet. The Smithsonian’s Separate Is Not Equal project noted that this vagueness “gave segregationists the opportunity to organize resistance,” turning “all deliberate speed” into all possible resistance.

Conservative political forces quickly took advantage of the opportunity. In 1956 the Southern Manifesto was signed by 101 members of Congress, 19 senators and 82 representatives from the eleven former Confederate states. The first draft was written by Strom Thurmond, who laced the document with vitriol and argued that states had a right to nullify a Supreme Court decision. J. William Fulbright from Arkansas worked on the final draft of the manifesto and massaged its language. Fulbright signed the final document.

One of Texas’s two senators, Lyndon B. Johnson, declined to sign. Johnson was then Senate Democratic leader and, although he had a segregationist voting record in the 1950s, he chose not to join the formal manifesto against Brown v. Board.

In 1957 Arkansas governor Orval Faubus used the state National Guard to prevent the “Little Rock Nine” from entering Central High School, provoking a constitutional crisis. President Eisenhower responded by federalizing the Guard, sending in the 101st Airborne Division, and issuing Executive Order 10730 to enforce the court’s desegregation order.

EO 10730 marked the first time since Reconstruction that a president sent federal troops to the South to uphold Black civil rights and federal court authority. Eisenhower was not an activist supporter of civil rights. His motive was less about remedying a national wrong, more about safeguarding federal power. He wrote, “There must be respect for the Constitution—which means the Supreme Court’s interpretation of the Constitution—or we shall have chaos.”

President Eisenhower didn’t have any more authority than his predecessors in the White House. Chaos came.

In Cooper v. Aaron (1958), arising from Little Rock, the Supreme Court unanimously held that states are bound by its interpretation of the Constitution and cannot nullify or evade Brown, directly rebuking Strom Thurmond and Arkansas’s resistance. The Court rejected Arkansas officials’ attempt to postpone desegregation at Central High School.

In Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (1964), the Court ordered Prince Edward County to reopen and operate public schools on a nondiscriminatory basis. Shutting down the county’s entire public school system while helping fund private White schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

As we’ve seen, busing as a strategy gained steam in the 1960s despite heavy resistance. It’s almost as if the will to send children to school across racial and ethnic lines for the greater good of society was part of a rebirth, an awakening, that ironically in today’s vernacular has been reduced to “woke.”

In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg (1971) the Supreme Court affirmed busing as a constitutionally permissible desegregation remedy. Swann began working its way slowly to the Supreme Court starting in 1964 when Black families sued Charlotte-Mecklenburg Schools for refusing to integrate. The Court in 1971 not only affirmed federal oversight of desegregation, a necessary part of the change for the better in school outcomes that was to be documented later by researchers, the accountability that No Child Left Behind lacked, but also established busing as the national mechanism for achieving it.

Following the Swann decision, integration kicked into high gear. Federal courts ordered busing plans across the South and in Northern cities where de facto segregation had concentrated Black students in urban cores. For roughly fifteen years, the strategy produced measurable results. Black and White children shared classrooms at rates unprecedented in American history. Longitudinal research would later demonstrate that Black students who attended desegregated schools during this period experienced substantially improved life outcomes: higher graduation rates, increased college attendance, greater earnings, and better health—with no measurable harm to White students.

But the legal architecture was already cracking. Milliken v. Bradley (1974) shielded suburban districts from metropolitan desegregation orders unless plaintiffs could prove the suburbs themselves had intentionally segregated. The ruling effectively protected White flight destinations from court mandates. Families who could afford to leave the cities did so, draining urban districts of White enrollment. Others enrolled children in private “segregation academies” that remained beyond federal reach.

Integration peaked around 1988, then the numbers reversed. Schools were Whitening again. By the late 1980s, courts began releasing districts from federal oversight, deeming them “sufficiently desegregated.” As White families fled, intra-district busing became mathematically futile: You cannot integrate an increasingly segregated city by moving Black students within it

By the late 1980s, courts began releasing districts from federal oversight, deeming them sufficiently desegregated. Freeman v. Pitts (1992) accelerated this trend by loosening supervision standards. The case involved the DeKalb County School System (DCSS) outside Atlanta, which had been under a desegregation order and later asked the federal court to declare it “unitary” and end supervision.

The lower court found that the school system had complied in some areas like student assignments, transportation, facilities, and extracurriculars, but not in others such as faculty assignments, resource allocation, and quality of education, and it partially lifted supervision in the compliant areas.

The following excerpt from the Supreme Court decision provides a sense of the granularity and complexity involved in monitoring districts across the country. Viewed from the perspective of a Supreme Court Justice making decisions about constitutionality, this excerpt suggests a dawning recognition that integration was no longer the work of the Courts. It was just too detailed, and court officers simply couldn’t second guess the details of running a school system.

“The District Court did not have this Court's analysis before it when it addressed the faculty assignment problem, and specific findings and conclusions should be made on whether student reassignments would be a proper way to remedy the defect.”

The Court held that federal district courts may withdraw supervision and control incrementally, releasing a school district from oversight in particular areas where it had achieved compliance even if the district is still not “unitary” in all aspects. The combination of legal retreat, demographic shifts, and political exhaustion allowed resegregation to proceed through the 1990s and beyond.

In 2007, Chief Justice John Roberts put the nail in the coffin of desegregation in Parents Involved in Community Schools v. Seattle School District No. 1 (2007) and applied an inscrutable logic when he wrote that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” Simple.

The case involved public school districts in Seattle and in Jefferson County, Kentucky. The core issue was whether public school districts that were not under a desegregation order could use individual students’ race as a factor in school assignment for the purpose of maintaining racially diverse, integrated schools.

Parents challenged these plans under the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, arguing that any use of race in assigning individual students to particular schools was unconstitutional racial classification, even when the stated goal was integration.

Chief Justice John Roberts’s controlling opinion concluded that these voluntary integration plans were unconstitutional because they classified and assigned individual students explicitly by race, and the districts were not remedying their own prior de jure (legally mandated) segregation. Seattle’s plan used race as a last‑resort tiebreaker: When too many students chose an oversubscribed school, assignments favored applicants whose race would move the school closer to its target racial balance. Roberts illustrated his concern with the case of a student with learning disabilities who was accepted into a selective program but denied placement at his preferred school because the racial tiebreaker worked against him.

In his most famous line from the case, Roberts wrote, “The way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race.” In practical effect, given that what was being struck down were voluntary integration plans, this translated into “the way to stop integrating on the basis of race is to stop integrating on the basis of race.”

Legal scholars describe his statement as a tautology, i.e., an instance of circular reasoning (Powell, 2024). It assumes discrimination is only about skin color, not about the unequal conditions that skin color marked in law by design for centuries in America. Scholars argue that by treating any race‑conscious state action as suspect, Roberts collapsed the distinction between Jim Crow laws that segregate and Brown laws that attempt to remedy segregation, including affirmative action. The facts of resegregation evident in 2026 empirically prove Roberts wrong.

Roberts’ formulation worked for those with ears to hear it because it sounds principled. Who could object to stopping discrimination? But the principle is false. Marking race to subordinate and marking race to remedy subordination are not the same act because both involve race, any more than throwing someone into the water and throwing them a life preserver are the same act because both involve water—and then argue that the way to stop drownings is to stop throwing life jackets.

Justice Stephen Breyer, joined by three other justices, dissented, arguing that the Constitution permits and sometimes requires race-conscious measures to dismantle racial segregation and promote integrated and therefore equal educational opportunity. I place emphasis on the word “dismantle” and its implied need for evidence of the absence of invisible institutional racism burrowed into placement mechanisms. I prefer the tie-breaker as a guardrail to prevent the slipping back that really did happen.

Justice Sonia Sotomayor answered Chief Justice Roberts in a 2014 case about affirmative action in Michigan, Schuette v. Coalition to Defend Affirmative Action. She argued that “race matters” because of ongoing, concrete harms such as stereotyping, exclusion, and the feeling among minorities that they “do not belong.” Sotomayor hearkened back to DuBois’ argument against integration—Black children needed the sympathetic touch he wasn’t sure White teachers had. Race matters not because it is marked by skin color but because it is embedded in our Constitution, our Civil War history, our endemic Ku Klux Klan, our turn to school buses as a last resort, and in intergenerational wealth transference heavily favoring the White population..

The Seattle Times published a story in 2023 documenting Seattle’s return to segregation. This online article presents a dynamic map of Seattle, switchable between 1936 and 2023, graphically depicting the similarity between real estate redlines from 1936 and modern day district boundaries. Roberts succeeded beyond his wildest dreams in returning the U.S. to segregated schools.

Litigation about the Green on the Road to the Promised Land

After the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in San Antonio ISD v. Rodriguez (1973), which rejected a complaint about unequal school funding based on the premise that the Constitution protects the right to schools, litigation over school finance shifted largely to state courts where advocates relied on state constitutional guarantees of adequate and equitable education. Many state high courts have found their states’ funding systems unconstitutional and ordered more equitable or “adequate” funding, which in some states has led to sizable increases in spending in high‑poverty, high‑minority districts.

Providing equitable resources to prevent a return to “green follows White” is contested in our society. Wealthy White people sometimes see no reason why they shouldn’t be able to spend whatever they like on their children’s schools. Nor do they believe they should be liable to pay for the education of other people’s children. Recent evidence suggests that children in poverty continue to attend under-resourced schools, many of whom are minority children. Allegretto et al. (2022) argued that “a larger federal role would boost equity and shield children from disinvestment during downturns.

Funding and attendance patterns both changed between 1954 and 1988, and then in many cases attendance drifted back into old patterns, particularly in inner cities and in the South. Funding slowed its progress toward equity as well, but positive changes in state funding mechanisms have fortunately become permanent. Though integration hasn’t permanently improved since Brown, funding patterns have.

Empirical Effects of Integration

Quasi‑experimental work on interracial contact in school cohorts (Merlino et al., 2022) asked whether interracial contact in school changes White adults’ later residential choices. Using Add Health data, Merlino et al. (2022) take advantage of quasi‑random variation in the share of Black peers across grades within the same schools, focusing on same‑gender classmates.

They then link those students about 20 years later to the racial composition of their census tracts. White students who had more Black classmates in 1994–95 subsequently lived in neighborhoods with more Black residents, even though their earnings, education, and neighborhood income or property values did not differ. The authors argued that this pattern reflects durable shifts in racial attitudes and reduced White flight rather than economic constraints or simple network effects. Reduced White flight meant more integration in neighborhoods just when school resegregation was taking off.

Other quasi‑experimental studies of interracial exposure (e.g., in schools, the military, or randomized team assignments) similarly found political and behavioral effects, such as reduced far‑right voting, lower Republican registration in some contexts, or more cross‑group social ties, that are consistent with reduced racial threat perceptions and avoidance.

The contact hypothesis has empirical support beyond race relations in the U.S. A landmark meta-analysis from 2008 of 515 studies (713 independent samples, roughly 250,000 participants in 38 countries) reported that greater intergroup contact is reliably associated with lower prejudice with average correlations between -.2 and -.3 and even stronger correlations in more rigorous experiments. This pattern holds for racial/ethnic groups, including Black–White relations in schools.

Grant (1990) published an analysis that revealed a more nuanced understanding of the reasons integration not only improved learning, as NAEP data from the 1970s through 1990 show, but reduced prejudice. Grant saw that oversimplifying integration to Black and White limited ideas about solutions to the problem. White supremacists segregate many other groups of people by ethnicity, gender, and other labels.

Indeed, Merlino et al.’s (2022) analysis discussed above found that the impact of experiences with classroom integration on home buying behavior later in life was more subtle. White students who worked with Black students in high school in 1994 were more likely to live in mixed neighborhoods 20 years later. But White females who had more Black females in class were even more likely to be colorblind when buying a home. The same was true for White males who had more Black males in their classes. Gender interacted with race to produce even less downstream prejudice in home buying behavior. In my mind, these data explain why Sean Reardon at Stanford found that neighborhood integration is better today than it was before busing than school integration, which is reversing itself..

Grant (1990) recognized this complexity. Although he didn’t look at gender, he did look at different racial and ethnic characteristics of students in classes. Grant insisted that desegregation policy must account for the varying concentrations and cultural characteristics of Hispanic and Asian-American students, not only Black and White.

His students came down in the same place Grant also insists upon, namely, that successful downstream integration depends upon professional expertise among school personnel. One of Grant's students concluded that the hardest problem was changing school staff attitudes and building their knowledge base in multicultural education.

Long-Term Trend NAEP data (Ferguson, 2001) indicate that from the early 1970s through the late 1980s, Black students’ average reading and math scores rose substantially and Black–White test-score gaps narrowed, with some estimates showing the reading gap for 17‑year‑olds shrinking by nearly half, and the math gap by about one‑third by the mid‑1990s.

Analyses of NAEP trends emphasize that Black and Hispanic gains in the 1970s and 1980s were often larger than White gains, especially at ages 9 and 13, meaning the cohorts in school during the height of desegregation showed the fastest convergence in basic skills. School integration coincides with the period when racial achievement gaps closed most rapidly and support the inference that those achievement gains are one mechanism behind later gains in adult outcomes.

The story from NAEP suggests that integration did a much better job of closing the achievement gap than No Child Left Behind, which substituted standardized testing and draconian accountability for busing as the mechanism for change. Where the move to integrate schools required embodied participation, real work in classrooms, real buses carrying children to new schools. NCLB offered nothing real to schools beyond standardized testing mandates and threats of punishment by withholding resources or closing down schools.

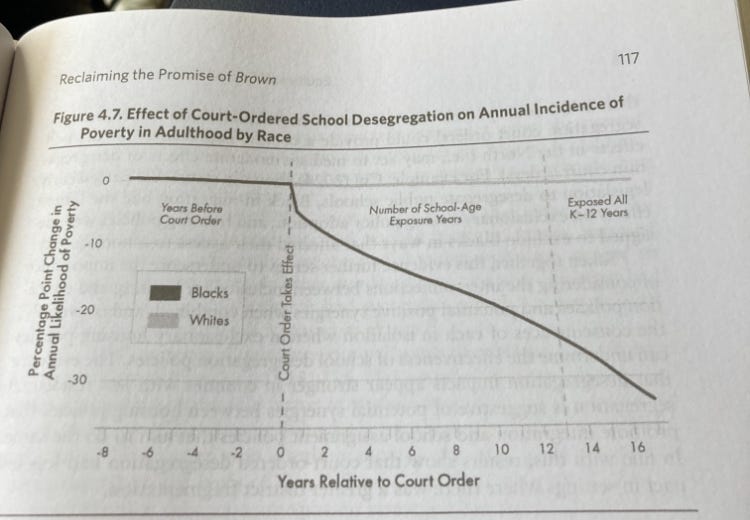

Longitudinal research now demonstrates incontrovertibly that Black students who attended desegregated schools between 1971 and 1988 experienced substantially improved life outcomes: better graduation rates, greater college attendance, greater earnings, and better health—with no measurable harm to White students (cf: Johnson and Amerikaner, 2025, Chapter 4: Reclaiming the Promise of Brown in Nasir and Darling-Hammond, 2025, Equity and Education Since Brown v. Board, Teachers College Press). The following visual provides insight into both the method and the credibility of the findings.

Years relative to the court order. The bottom horizontal line depicts number of years following the Supreme Court’s first clear endorsement of desegregation as a remedy in 1971, in Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education. In Swann, the Court unanimously held that federal judges could require pupil transportation within a district to achieve racial balance in formerly segregated school system.

This court action divides school experiences into two groups. In one group (post-1971 through 1988) we have students who learn in mixed race classrooms; if we view this circumstance as an experiment, this group would be the treatment group. Students who did not participate in integrated classrooms (the White students who lived in the suburbs, the Black students in the inner city) would be in the control or comparison group.

The line beginning its descent in 1971 continues its descent until we find that children who had been exposed to integration all twelve years they were in school (the treatment group with the maximum dose) are 30% less likely to live in poverty as an adults than those who had not experienced a full twelve years in racially integrated schools.

What Changed for the Treatment Group?

Contesting the White Gaze in Integrated Classrooms

Theorized by Fanon, linked with Foucault’s triangle of power through a critical feminist lens by bell hooks, and clarified in terms of its operation in American literature by Toni Morrison, the ‘[W]hite gaze’ names a complex racialized mode of perception that sees Black bodies as objects of scrutiny, domination, assessment, and judgment.

For the treatment group of young American children, White and Black, male and female, given the chance to go to school together from kindergarten to high school graduation, the change came in the nature of the White gaze.

Franz Fanon

The coiner of the phrase, Franz Fanon was born in 1925 in Martinique, trained in medicine and psychiatry in France, and worked as a psychiatrist in colonial Algeria. Adam Shatz’s new biography, The Rebel’s Clinic: The Revolutionary Lives of Frantz Fanon (2024, Farrar, Straus and Giroux), revisits his life and work.

As a huge heading in a cosmic outline, the active semantic significance of Fanon’s phrase during the 1960s and beyond in the U.S. reveals a consistency between 18th century Western White colonialism globally and local White American manifest destiny. White America not only took the land from indigenous people from sea to shining sea, it taught them the horrific consequences of resistance once caught in the White gaze.

In his book Black Skin, White Masks (1952), in the chapter translated from the French as “The Lived Experience of the Black Man,” Fanon described the sudden feeling of being turned into an object. “I am being dissected under [W]hite eyes, the only real eyes,” Fanon wrote. “I am fixed.”

Fanon is canonical in university curricula, taught alongside Said and Spivak in postcolonial theory, foundational in Black studies. According to Said (1973), Western scholars didn't describe the Middle East and Asia, they constructed "the Orient" as a concept to serve European power (Orientalism). The "Orient" in the [W]hite Western imagination was exotic, irrational, sensual, despotic, an alternate world mirroring everything Europe was not but secretly craved.

Spivak pushed further and sharpened the point. In “Can the Subaltern Speak?” (1988), channeling Antonio Gramsci, she argued that those at the very bottom of colonial hierarchies—particularly poor, colonized women—are misrepresented, yes, but structurally prevented from being heard as speaking subjects at all. Her famous formulation “White men are saving brown women from brown men” captured how imperial power and the Western White male eye constructed colonized women as objects of rescue rather than agents of their own lives.

Fanon expressed the phenomenology of being seen as the Other, Said demonstrated the discursive construction of the Other, and Spivak made us hear voices coming from the silence that follows from that construction. All three converge on the same insight from different angles: Perception is never neutral, and those who control representation control who counts as fully human.

A new generation knows hooks through All About Love (2000), which entered the New York Times bestseller list in 2020 and now circulates virally on TikTok as relationship wisdom. But the hooks who theorizes the oppositional gaze is the cultural critic, not the love guru. In "The Oppositional Gaze" (1992), hooks takes Fanon's insight about being fixed and asks what happens when Black spectators look back. Where Fanon described subjection—"I am fixed"—hooks theorizes resistance: the subaltern who refuses to be fixed, who looks back.

bell hooks

bell hooks inherited this critical way of thinking about colonizing the world but dwelled on the American context and the gendered dimension of Black women’s spectatorship. hooks took note of Fanon’s missing account of women and Black women in particular under the scrutiny of the White gaze—and crucially, theorizes resistance to the gaze rather than conditions of subjection to it. The oppositional gaze is what the subaltern develops when she refuses to be fixed.

For hooks, the White gaze is a position in which White people and White institutions assume they are the default audience, subject, and standard with Black people positioned as objects to be watched, managed, or explained. Her experiences as a Black child disciplined by her parents for looking directly into the eyes of Others taught her to defer to and look away from the White gaze. The lesson clearly didn’t take. As a Black woman, she took her place in space and time as her own and looked back, around, through, and into.

Toni Morrison

Toni Morrison explicitly framed her fiction as a sustained effort to decenter the White gaze, a stance in sharp tension with the “colorblindness” associated with Chief Justice John Roberts, which treats race as something the White law can and should largely ignore. Morrison used the White gaze as a frame for understanding her fiction as consciously written outside an assumed White spectator‑reader

The single Toni Morrison work that best illuminates her thinking is Playing in the Dark: Whiteness and the Literary Imagination (1992). In that book, Morrison explicitly analyzes how White-authored American literature is structured around an assumed White reader and an “Africanist” presence, which is precisely the dynamic of the ‘[W]hite gaze.’

Morrison’s book helped to engender an entirely new sub-field that didn’t exist when she wrote it, what we now call “whiteness studies.” Tevis et al. (2023) published a paper seeking to pull together a theoretical framework for studying Whiteness. Here is a lengthy bibliography citing over a hundred recent papers in this field. The authors argue that whiteness studies have often failed to apply a consistent understanding of whiteness as ideology and has sometimes overlooked the material consequences for people of color.

Applebaum (2021) published an article examining some challenges that White educators who interrogate Whiteness with White students encounter. According to the abstract, two dilemmas are discussed. Is it supporting White students’ learning to teach from the place “where the student is” and/or is it “colluding with [W]hiteness” by protecting [W]hite fragility, including one’s own? When a White student says something in a discussion about race—say, "I don't see color" or "My family never owned slaves"—should the White teacher hear it as a genuine question deserving a thoughtful answer, or recognize it as a defensive maneuver designed to distance the speaker from implication of Whiteness?

Casting Out the White Gaze

What changed for those students who spent twelve years in integrated classrooms? What happened in the treatment classrooms of America during that wonderful social experiment the Supreme Court started, fostered, and then stopped prematurely? Allport’s contact hypothesis offers the mechanism—equal status, cooperation, common goals, institutional support—but Fanon, hooks, and Morrison explain why those conditions matter.

Integration under the right conditions disrupted the White gaze. White students could not maintain the position of unmarked observer, the “only real eyes,” when Black classmates were present not as objects to be assessed but as subjects who looked back. Fanon’s “I am fixed” describes a unidirectional power: the White eye dissects, the Black body is dissected. But in a classroom where teachers enforced equal status and structured cooperation toward shared goals, that unidirectionality broke down. Black students refused to be fixed. They returned the gaze.

This is what hooks theorizes as the oppositional gaze—not just being noticed as an Other occupant in the room who shouldn’t be there, but seeing back, and in that returning look, disrupting the assumption that Whiteness is the default from which all Others deviate. Over twelve years, repeated daily, these reciprocal gazes did something that no curriculum about tolerance could accomplish in Whites-only classrooms: it made the racialized perception visible to those who had been trained not to notice it, the White population.

Morrison’s insight clarifies the stakes. White-authored American literature, she argued, assumes a White reader and constructs Blackness as a shadowy “Africanist presence” against which White identity defines itself. Integration interrupted that literary structure in lived experience. White students who worked alongside Black peers for twelve years could no longer sustain Blackness as abstraction, as symbol, as what Morrison called the “not-me.” The Other became a person with a name who sat in the next desk and sometimes knew the answer when you didn’t.

This is what Whiteness studies in education now struggles to reproduce deliberately without the ecology of integration. Applebaum’s dilemmas—how to teach White students about Whiteness without colluding with their fragility—are dilemmas precisely because the integration that once disrupted the White gaze through daily lived contact has ended. Teachers are asked to accomplish through pedagogy what twelve years of structured integration accomplished through relationship, making Whiteness visible to those who inhabit it.

Those White folks who cannot see themselves implicated in the White gaze are those whom John Roberts might think of as “woke.”

Du Bois doubted that White teachers had the “sympathetic touch” to teach Black children. The integration data suggest something complementary: Black presence, under the right conditions, taught White children something about themselves that White teachers alone could not. The treatment group didn’t just learn tolerance. They learned to see themselves being seen.

How can Roberts declare colorblindness the law of the land from the bench while Morrison testifies to a gaze that fixes and dissects? The answer is not that one is lying and the other telling the truth. The answer is that Roberts is not aware of what he does not see, of what DuBois called the sympathetic touch, of what might happen if Black becomes valued as highly as White, if Black children and White children are valued equally because they are the future of humankind.

Joyce King (1991) named this disposition of colorblindness “dysconscious racism”—an uncritical habit of mind that tacitly accepts dominant White norms and privileges as natural, inevitable, and neutral. Dysconsciousness is not overt hostility nor hatred. It is a cognitive absence, a perceptual disability, the inability to perceive structures that benefit oneself at the expense of Others and then question the moral consequences, the conviction that one’s own perspective is universal, the sincere belief that one does not see race.

Dysconsciousness in the Research on White Teachers

We have empirical evidence that White teachers have a tendency to exist in a dysconscious state of mind. Waymouth and Weary’s (2024) critical discourse analysis of eight White middle school teachers illustrates the kind of dysconsciousness I refer to, using King’s (1991) dysconsciousness framework and Applebaum’s (2010) concept of White complicity.

This 2024 study was a re-analysis of data from two earlier studies that had not been designed to examine race at all. The original interviews asked teachers about literacy instruction, not about race or equity. Because of this focus, the teachers weren’t primed to give rehearsed or socially desirable answers about race. They were enacting Whiteness, not interrogating it.

When asked to describe their own race, teachers exhibited hesitation across multiple interviews. Only one answered directly: “White.” Others preferred “Caucasian,” with one adding “or whatever it is these days” and another pausing before responding “White, um, Caucasian.”

When discussing literacy instruction, no teacher directly mentioned race or ethnicity. Instead, several used terms that function as code: “demographic,” “low-income,” questions “not meant to ruffle feathers.” Verbal pauses appeared immediately before descriptions of students or racial contexts that differed from the teachers themselves.

A teacher planning a genetics unit had selected a news story about twin girls who appeared to be from different racial backgrounds as the unit’s anchoring phenomenon. She voiced her anxiety to peers during a planning session: “I’m nervous of teaching genetics because it involves sex. I’m worried what the kids will do with that. (pause) And then there’s the race issue too.” The group then spent extensive time discussing the school’s approach to sex education timing. They never returned to the race comment, not even after students engaged in the lesson and unit.

In a similar vein, King et al. (2023) examined how 39 undergraduate STEM instructors noticed anti-Black racialized events that were experienced by students in classroom narratives. The following quote from the abstract aligns with conclusions from Waymouth and Weary (2024):

“Color-evasive racial ideology was pervasive, with most responses (54%) avoiding any discussion of race, and few responses acknowledging race or racism in more than one event (10%). We characterized six forms of color-evasiveness. This study adds to a growing body of literature indicating that color-evasion is pervasive in STEM culture.”

In America the teaching force remains overwhelmingly White while the student population grows increasingly diverse, a demographic reality that places dysconsciousness at the center of educational practice. DuBois’ worry about the loss of a sympathetic touch as a consequence of a dysconscious White-centric version of instruction looms large.

Flores and Rosa (2015) bring us closer to a pedagogical remedy. The White gaze gets operationalized in the notion of raciolinguistics and its core concept: the White Subject. Incorporating raciolinguistics in the curriculum of teacher preparation and requiring credential candidates to experience mentored teaching in diverse classrooms offers a starting point. In essence, White teacher prep students would be the ones to get bused from suburban White schools to urban schools during the credentialing process.

The White Speaking and Listening Subject

A framework that gives theoretical specification to what dysconsciousness produces comes from Flores and Rosa’s (2015) concept of raciolinguistic ideologies. Flores’ and Rosa’s argument begins with a deceptively simple observation: People are positioned as prestige or non-prestige speakers based not on what they actually say with language but on how they are heard.

The White gaze, they might argue, serves a White speaking subject, who engages in the idealized linguistic practices of Whiteness, and to the same subject when they are listening, who hears and interprets the linguistic practices of racialized populations as deviant.

Crucially, the White speaking and listening subject “…should be understood not as a biographical individual but as an ideological position and mode of perception that shapes our racialized society” (Flores & Rosa, 2015, p. 151).

The teacher as a speaking and listening subject is not just an ideological abstraction. The White subject is made manifest in a person with a credential, a grade book, and the institutional authority to pass and fail. Credentials provide the intellectual framework to speak authoritatively, to reward and punish, at the front of the classroom; the grade book provides the enforcement mechanism based on how the teacher listens. The credential says: This person's ears are authorized to judge.

This preparation traditionally has little to do with skin color. A Black teacher can occupy a role taking up the White subject position just as easily as a Hispanic teacher or a White teacher. In his 2019 autobiographical reflective essay, Flores discussed how, as a Latino ESL teacher, he insisted his Latino students' bilingualism was deficient, reproducing the same deficit framing that had marginalized him as a child. He had become the White listening subject.

He wrote: “I convinced myself that teaching my students the ‘codes of power’ (Delpit, 2006) was the most effective way of countering this legacy of poor instruction and ensuring their academic success” (p. 49). Only later did he recognize the trap. “Ironically, I had gone from being a Latino child whose English and Spanish was deemed not good enough to a Latino adult insisting my Latina/o students’ English and Spanish was not good enough” (p. 49).

Teaching racialized students to produce “appropriate” language, the goal of most language education, cannot succeed on its own terms. No matter how closely students model themselves after the White speaking subject, the dysconscious White listening subject continues to hear those students’ language as marked, deficient, inappropriate.

Knowledge of a student’s race, ethnicity, and discursive linguistic background shapes how the White teaching subject listens. The problem is not primarily in the mouth of the teacher speaking subject but in the ear of the teacher listening subject.

What broke this cycle in Flores’s personal teaching experience was his encounter with Ofelia García’s theory of translanguaging. The traditional view of bilingualism assumes two separate language systems housed in the mind, discrete codes that the competent speaker keeps properly apart. Translanguaging rejects this architecture.

Bilinguals operate with a single integrated repertoire, deploying features strategically across contexts in ways that monolingual frameworks cannot begin to comprehend, let alone evaluate. What we think of roughly as “language mixing” or “code-switching”—and consistently stigmatize—is not confusion or deficiency but sophisticated linguistic practice, evidence of a larger repertoire rather than a smaller one.

Flores illustrated translanguaging through his own childhood. His parents communicated with each other primarily in Spanish but addressed their children bilingually—his father using more Spanish, his mother more English—while the children responded primarily in English.

“Though I did not have a word to describe it at the time,” Flores writes, “I now realize that translanguaging was the norm in my household” (2019, p. 47). When classmates in high school Spanish accused him of having an unfair advantage, he told them he did not speak Spanish. “They could not believe that it was possible for somebody to understand a language that they could not speak” (p. 47).

García’s translanguaging framework allowed Flores to see his students’ fluid movement between English and Spanish not as failure to master either language but as mastery of something more complex than monolingualism can imagine. Yet Flores came to see that even translanguaging, embraced in the context of an externally imposed set of lessons without attention to race and ethnicity, could not dismantle the underlying structure.

The White listening subject does not evaluate linguistic practice; it evaluates racialized bodies. As Flores and Rosa (2015) argued, “appropriateness-based approaches to language education presupposed that students from racialized backgrounds had full control over their language practices failing to account for the role of the [W]hite listening subject in overdetermining their language practices to be deficient” (Flores, 2019, p. 54).

In Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black English Vernacular (1972), linguist William Labov directly attacked the then-dominant “verbal deprivation” theory, which claimed that Black inner-city children received little language stimulation and therefore had impoverished, deficient language. He showed, through detailed recordings and analyses of children’s peer-group talk, ritual insults, and narratives, that Black English Vernacular is “…a well-formed set of rules of pronunciation and grammar capable of conveying complex logic and reasoning,” and that earlier deficit studies simply failed to see this sophistication. The White listener as scholarly researcher heard what it was authorized to hear and did not have DuBois’ sympathetic touch.

Flores and Rosa (2015) showed how the issue was never about language: “No matter how much was added and how adept racialized students became at conforming to rules of appropriateness, they would always be heard as utilizing racially marked language practices that are inappropriate because of their racial position within the broader society” (p. 54).

This is the mechanism that connects dysconsciousness in White teachers to poor learning outcomes for racialized students, Black or Brown. It is also the mechanism that leaves White children in all-White affluent schools undisturbed as inheritors of the White gaze. The dysconscious teacher is not malicious, just dysconscious; they are the White listening subject, hearing deficiency where none exists, hearing deviance even in standard forms, hearing silence as confirmation of what they already believe. It is worth repeating that the White speaking and listening subject is not an individual, not a person, but a role.

And here the classroom converges with the courtroom. When Chief Justice John Roberts declared that “the way to stop discrimination on the basis of race is to stop discriminating on the basis of race,” he was not being dishonest. He was speaking from inside the same White cognitive structure he was affirming—one that cannot perceive its own perceiving. He was speaking as a dysconscious Supreme Court Justice.

Roberts made a career of colorblindness not because he aimed to consciously deceive others but because the White listening subject cannot hear itself listening, and he is a White listening subject. The dysconscious teacher and the colorblind jurist inhabit the same axiological position: Both believe themselves to be perceiving neutrally, generously, patiently, and both are utterly incapable of recognizing what their perception excludes.

The Automated White Speaking and Listening Subject

It’s ironic that LLMs have drawn such high heat in the professional talk among teachers and professors about their value of legitimizing a tool for cheating. This is a devastating set of circumstances that calls for fresh thinking not so much about LLMs but about teaching itself. Rather than creating the problem, LLMs expose the architecture of the problem with a foundation in historically produced sociocultural and relational asymmetries, not as a need for specialized lesson designs that restrict and control uses of LLMs.

The standardized assignment—same topic, same format, same rubric for everyone—is itself a technology of the White listening subject. The teacher isn’t asking “What do you think?” but “Can you produce what I expect to hear?” The rubric encodes the listener’s expectations. The prompt defines the acceptable range of response. The format dictates how thought must be packaged to count as thought. Students learn quickly that the game is not to think but to perform thinking in the register the listener recognizes as legitimate.

An LLM excels at precisely this task. It has processed millions of examples of what academic writing sounds like to the institutional ear, and it can reproduce appropriate patterns. Let that sink in. LLMs can give the White teacher listening ear exactly what it wants to hear. Does it not follow that the LLM can replace both students and teachers?

Does it not explain why, lately, teachers across the country have been warming up for scaled uses of LLMs to evaluate student writing? So what if it means constraining what counts to student writing completed in the presence of the White gaze? News coverage, early research, and ed‑tech promotion all point in the same direction: LLM‑based tools are rapidly moving from pilot projects to normal options for grading and feedback.

So why not cheat? It produces fluent, competent, properly formatted prose that satisfies rubrics because rubrics describe exactly the kind of standardized output LLMs are trained to generate. The LLM is, in effect, the ideal student for the White listening subject. It never deviates, never surprises, never talks back, never brings an oppositional gaze to the assignment. It produces what the listener expects to hear, and nothing else.

The cheating panic thus reveals something teachers would rather not confront. The assignment was never meant to evoke thinking from deep in the learner. It was meant to create conformity to expectations. When a machine can satisfy the rubric, the rubric stands exposed as a mechanism for sorting compliant performers from non-compliant ones, not for identifying who actually learned something about writing or had something to say.

Flores and Rosa (2015) seems highly relevant. The White listening subject hears racialized speakers as deficient regardless of what they actually say; the linguistic form gets filtered through an evaluative frame that pre-judges the speaker. The standardized assignment works the same way in reverse: it rewards outputs that conform to what the listener already expects, regardless of whether genuine thinking produced them. Both are technologies for reproducing the listener’s assumptions rather than encountering an actual other mind.

Large language models are not neutral tools. In addition to their emergence as tools students use to subvert the intentions of their teachers, they are the White speaking and listening subject automated and scaled. When a student submits an original blue-book text to an AI writing assistant, the model evaluates that text against norms derived from a training corpus that systematically over-represents White English and cultural perspectives.

Guo et al. (2024) classify these biases as intrinsic and extrinsic. Intrinsic biases originate from the training data as well as the architecture and assumptions made during model design. Certain demographic groups may be either underrepresented or misrepresented within training datasets. Extrinsic biases show up during real-world tasks. LLMs used in hate speech detection, for example, could disproportionately flag certain dialects or vernaculars, such as African American Vernacular English (AAVE), as more offensive compared to standardized English, reinforcing societal stereotypes.

Because Western colonial style biases are embedded in human language and text that produce and reproduce gendered, racial, cultural, and socioeconomic stereotypes, when AI is used in critical decision-making environments such as healthcare diagnostics and hiring processes as well as evaluating student writing, they can lead to unequal treatment that disproportionately affects marginalized groups.

Research confirms what theory predicts. When students prompt ChatGPT in non-standard varieties—urban vernaculars, heritage language-influenced English, dialectal forms—the model responds with corrections, with evaluations of inappropriateness, with the dysconscious White deficit perception that Flores and Rosa describe. There is no artificial sympathetic touch of the sort that made DuBois question the wisdom of integration when the teachers are White.

Put bluntly, LLM output is intertwined with the ideological assumption that racialized subjects’ language practices are unfit for legitimate participation in a modern world. The machine has learned to hear the way the White listening subject hears.

But LLMs are not only listeners. They are also speakers. When an LLM generates text, it produces what the training data suggests a competent, legitimate speaker would produce. It speaks in the voice of the White speaking subject: the idealized model of academic, professional, “appropriate” English that students are expected to emulate. Of course, LLMs can be prompted to generate dialects, to mimic speech patterns characteristic of stereotypes of well-known fictional or historical speakers and writers, but you have to be an experienced bot whisperer to get it to do your bidding.

A Nature study (Hoffman et al., 2024) on dialect bias shows that LLMs respond more negatively and stereotype more when prompts are written in African American English, even when they produce positive language about “African Americans” when prompts are written by the White speaking subject. It does not translanguage. It does not code-switch with the fluency of actual multilingual speakers. It produces the standardized, homogenized English that the White listening subject expects to hear and read from students.

The authority structure compounds the problem. Who decides whether students may access these tools? Who sets acceptable use policies? Who determines when AI-assisted writing counts as cheating and when it counts as legitimate support? These decisions rest with institutional actors—majority White administrators, teachers, policymakers—who are positioned as White listening subjects by virtue of their credentials and roles.

Empirical work is still emerging, but existing data and policy analyses suggest that AI is currently amplifying long‑standing inequities between majority‑Black/Minority and majority‑White classrooms in three main ways: access, how tools are used on students, and the kinds of bias those tools encode.

Surveys summarized by psychology and media organizations show that Black teens are at least as likely, and often more likely, than White peers to use generative AI for schoolwork, but Black students and non-native English speakers are also more likely to have their work wrongly flagged as “AI‑generated,” which can trigger discipline or grade penalties.

Conclusion: The Structure and Its Remedies

The situation is this. American public schools are staffed overwhelmingly by White teachers, many of whom function as dysconscious speaking and listening subjects—perceiving what they believe to be neutrally, often demanding neutrality of themselves, while evaluating racially and ethnically in fairness to their students who have to learn to do in a White world, they believe, believing themselves liberators while reproducing hierarchy.

The schools themselves are resegregated and resegregating, and the Constitution—as currently interpreted by a Court shaped by John Roberts’s four-decade project—offers no remedy. The colorblind jurist and the dysconscious teacher inhabit the same epistemological position, and the jurist has foreclosed the tools that might have interrupted the teacher’s reproduction of the social order mirrored in unjust and inequitable school attendance assignments.

Absent a federal constitutional amendment guaranteeing children the right to attend integrated schools—an amendment nowhere on the political horizon—segregation will proceed with judicial blessing.

States retain authority to act where the Court has refused. Property taxation as the primary funding mechanism for public schools ensures that segregation by residence produces segregation by resource. Redistribution models exist; political will to implement them does not exist in every state. Yet adequacy, if not excellence, remains achievable through state action.

Artificial intelligence enters this landscape as both problem and possibility. The automated White listening subject encodes the very perceptual structure that produces inequality in classrooms. But AI can also make that structure visible, provide alternative feedback mechanisms, and perhaps, with specially trained and tuned bots, impact the classroom teacher’s dysconscious monopoly on evaluation.

Systematic redesign can distribute the power of judgment—teaching students self-regulation and self-assessment rather than dependence on external arbiters whose ears are too often trained to hear deficit and socialized to expect little of the young people showing up in class today.

None of this undoes the structure. But naming it is the precondition for contesting it. The White listening subject prefers to remain invisible. Making it visible—for the learner, in the teacher, in the judge, in the machine—is where the work begins.