Hybrid Literacy and Oracy: Conversations Between Humans and Natural Language Bots

What are we talking about?

“The world our kids are inheriting is going to be full of A.I., and we need to make sure they are well equipped for it, both the benefits and the drawbacks,” Wade Smith, the superintendent of Walla Walla Public Schools, said in a recent interview. “Putting our heads behind the curtain or under the sheets and hoping it goes away is simply not reality.” (New York Times, September 9, 2023)

Pedagogical bending of the fabric of the curriculum as it is spun in the hands of a teacher takes time—year after year of teacher learning. Janet Hecsh uses the term “structures” of a curriculum in reference to elements in a curriculum which are made of more durable stuff, often immutable stuff, which can impede progress as much as it stabilizes the present. Wade Smith of the Walla Walla Public Schools speaks wisdom: Putting our heads behind the curtain leaves our behinds exposed, an invitation to the Gorgon sisters. You remember them from your nightmares, the three sisters in Greek mythology with snakes growing from their skulls, who turn mortals to stone on eye contact.

Collaborating with Jeffrey has been incredibly interesting. It’s been twelve years at least since I handed in my keys to the Office of Academic Program Assessment in the library at Sac State; this experience reminds me of what I miss most—the fascination of working with college professors on teaching practices in disciplines far from any expertise I might have had. Assessment in the early part of the physics curriculum, for example, was mystical in that the need was to parse out subtle yet entrenched misconceptions in learners experienced since infancy. No, you are not standing still. There was a standardized measurement tool, but the small department was united in an ongoing effort to improve on it.

The bot poses an assessment challenge on the order of magnitude of the rhetorical challenge Odysseus faced when he endeavored to persuade the great Achilles to set aside his rage after the King, Agamemnon, took Achille’s wife from him as a royal prize. Achilles, half mortal, half god, all but for his weak heels invincible in battle, refused to fight for the Greeks in their war with Troy. Nothing Odysseus could say would work. The bot, like Achilles, is emotionally other worldly, one completely consumed with emotion, the other totally devoid of emotion. The bot, like Achilles, has superhuman powers, one in battle, the other in computational logic and linguistic data analysis. The bot, like Achilles, has a fatal flaw, one bad heels, the other devoid of consciousness.

*****

How do subject-matter teachers assess the bot as a pedagogical tool with artificial intelligence? With a piece of chalk, a microscope, or a manipulative as a beginning point, a textbook, a lecture, a film, or a structured activity near the middle, and a bot as an endpoint—each a piece of instructional equipment capable of influencing learning with affordances and constraints—what can the bot do? How can a teacher use it productively in the students’ hands as a tool for learning? Even a piece of chalk is transferred from the hands of the teacher to the hands of the student, if only metaphorically.

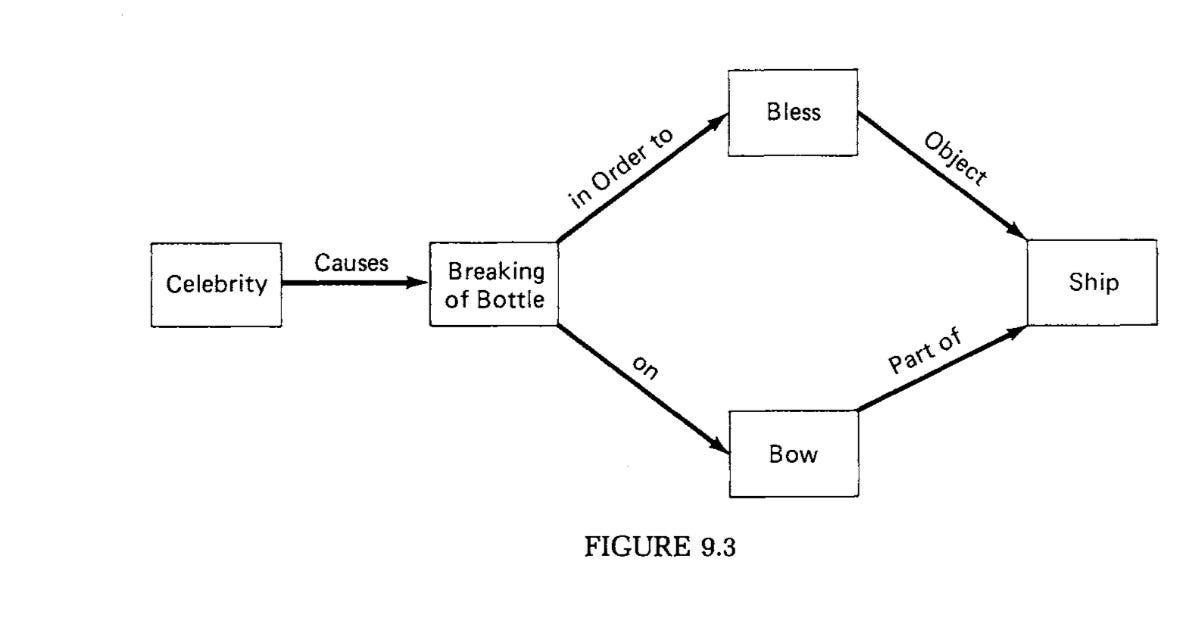

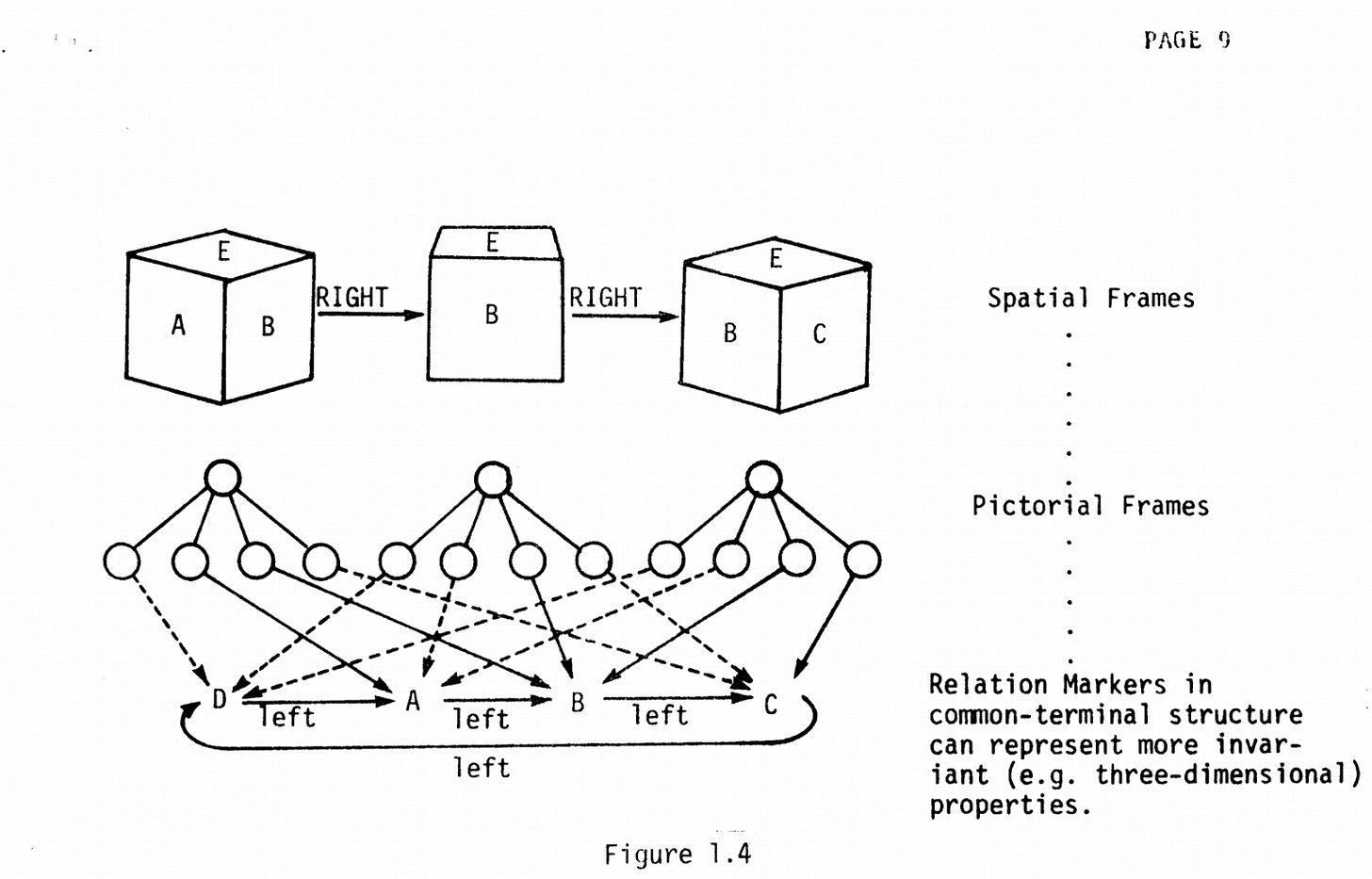

Undoubtedly, new doctoral students in the field of language and literacy are formulating possible dissertation topics emerging from this Achillean challenge. It is perhaps more apt to name the bot “Achilles” than, say, “Socrates.” I’ve been formulating some research topics along these lines related to PreReading instruction, grounded in Patricia Alexander’s (2012) take on relational reasoning with a hybrid notion of Minsky’s (1974) frame theory in computer science (Figure 1.4) and Anderson and Pearson’s (1984) model of schema theory in the field of reading (Figure 9.3).

Minsky wrote about the same topic that occupied Anderson and Pearson, that is, the organization of knowledge in a fashion that permits retrieval and rearrangement during reading to serve appropriately in comprehending or mirroring some part of the world or Bruner’s possible world: “A frame is a data-structure for representing a stereotyped situation,” Minsky (1974) wrote, useful in comprehending particular situations. Anderson and Pearson (1984) used a “stereotyped situation” as an example of a “schema” they referred to as the SHIP CHRISTENING schema. Notice, however, the differences in level of abstraction between Figure 9.3, Anderson and Pearson’s depiction, and Figure 1.4 Minsky’s depiction of a frame (identifying a cube). Anderson and Pearson are focused on human comprehension; Minsky is focused on programming a machine to comprehend in a humanlike way. It seems clear to me:

A fresh look at these diagrams reveals nuances in research approach depending on which entity was under the microscope, humans or bots. The christening schema is probably a better depiction of a human schema at the point of use; packed with meaning itself, every term labeled inside a square in the schema could be viewed as a mini-schema. You and I know what a “bow” is and can retrieve it in the same way we can retrieve a “ship” and a “bottle of champagne,” each of which might be considered a frame like a cube in Minsky’s shop. A machine would have to deal with each part of the schema individually to concoct organized prior knowledge. A human could retrieve it all in a burst.

Conversational bots would not become reality until almost fifty years after Minsky wrote about frame theory. Minsky could not take for granted that an artificial mind would so easily access “bow” or “champagne.” He wanted to figure out how to design a computer that could comprehend from the lowest level of demand. Humans had been comprehending texts for centuries and were pretty darn good at it when Anderson and Pearson analyzed the role of prior knowledge in comprehension and the cognitive processes enabling comprehension, largely in an effort to improve teaching and learning.

I asked the bot to help me analyze the parts of the ship christening schema. Witness:

- robot: Hello, How can I assist you?

- user: I’m working on an article and need some help understanding what the essential parts of the frame “christening a ship” are. What must be an element of the situation? What is optional?

- robot: When it comes to christening a ship, there are several essential parts of the frame that must be included, as well as some optional elements. Here's a breakdown:

Essential parts of the frame:

1. The ship: The presence of an actual ship is a vital element in the frame of christening a ship. It serves as the centerpiece of the event.

2. A person performing the christening: Typically, a designated person, often a prominent figure such as a godparent, sponsor, or dignitary, is responsible for performing the christening ceremony. This person's presence is essential.

3. A name for the ship: Before the christening, the ship needs to have a name which will be announced during the ceremony. The ship's name is an important element of the frame.

4. The christening ritual: The act of christening itself is crucial. It usually involves the person in charge, often using a bottle of champagne or another beverage, ceremonially breaking it against the ship's hull. This ritual symbolizes good luck and officially marks the ship's entry into service.

Optional elements:

1. Location and setting: While the christening ceremony often takes place at the shipyard or shipbuilding facility, it can also be organized at other locations, like a harbor, naval base, or during a special maritime event. The choice of location can vary based on tradition or practical considerations.

2. Attendees and spectators: The presence of attendees and spectators can add to the celebratory nature of the event. This can include shipyard workers, crew members, family of the shipbuilders, military personnel, government officials, and even members of the general public. The size and composition of the audience can vary.

3. Speeches and performances: Depending on the significance of the ship or the occasion, speeches and performances may be included in the ceremony. These can range from formal speeches by dignitaries to musical performances, poetry readings, or other cultural expressions.

4. Blessing or religious ceremony: In some cases, a religious blessing or ceremony may be part of the ship's christening. This can involve a clergy member or religious representative offering prayers or performing rituals to bless the ship and its crew.

It's worth noting that while the above elements are common in ship christening ceremonies, they can vary depending on cultural traditions, the type of ship, or the specific context in which the event takes place.

*****

Minsky (1974) and Anderson and Pearson (1984) comment on Bartlett (1932) as a seminal thinker in the quest to understand the reciprocal relationships among the human capacity storing information in useful forms, retrieving information as appropriate to purpose and situation, and taking in new information and making it available for future cognitive use. I mention this to underscore the parallels in recent history between the field of reading and field of artificial intelligence. Given that AI, though limited in comparison with human intelligence, is a machine operating in loose alignment with a schema theoretic view of reading underpinning what we know about comprehension instruction, it seems fair to explore the bot as a potential contributor to disciplinary reading comprehension.

*****

One pedagogical area vital to integrating the bot effectively into content area reading lesson design, PreReading, has taken on new significance. Lately, I’ve been curious about the fuzziness of the role of new knowledge in a situation where activating prior knowledge is the goal. For example, the PreP strategy, a staple in secondary methods courses, involves both activating and pooling prior knowledge: Step one = brainstorming, Step 2 = organizing the raw lists, Step 3 = reflecting on the prior knowledge map resulting from step two and preparing to use newfound topical coherence and knowledge during reading. The strategy involves old and new learning as well in that, as a whole class activity, students share information other students might not have known.

Enter the bot. As the SHIP CHRISTENING example from the bot reveals, it is possible to bypass brainstorming and use the bot to create a prior knowledge map. Suppose a reading assignment focused on technical aspects of carbon in the context of global warming. Students could prompt the bot to outline the essential elements of a “frame” or “schema” titled “carbon footprint.” In a race horse experiment pitting individual bot work aimed at producing a prior knowledge map designed to enhance coherence during reading vs. collaborative human brainstorming, which approach works better? Might the bot work better with students who have little prior knowledge while PReP is more effective with students who have a certain level of prior knowledge?

Suppose step one, brainstorming, was done in a whole class discourse setting. Step two, organizing the list into categories, might be carried out individually, in pairs, or in small groups with bot assistance. Or step two could be carried out by small groups with candidate knowledge maps for individual readers take with them into the text to elaborate individually with the bot. Because such in class work allows for control of the bot, it could also serve to educate learners in the pragmatics of bot interactions.

How will we ever know with our heads inside the curtain and our bottoms exposed to whatever made us hide our heads in the first place?