Giving, Getting, Grappling with Feedback: Improving Writing, Writers, and Readers in a Community of Practice

Interest and Intention in Literacy

How’s that for alliteration? Systematic, explicit instruction in students’ giving and receiving feedback keyed to a writer’s intentions for a piece or collection of pieces isn’t usually a high-level objective in the official writing curriculum. It’s production that garners good grades. Nowadays topics like making a claim, amassing textual evidence for the claim, addressing counterclaims, etc. get top billing—and form and structure, can’t forget form and structure—and conventions.

During the olden days of portfolio instruction, feedback was beginning to surface as a core concern, but the backlash that swept away portfolio pedagogy—it came on us like a flash flood somewhere around the turn of the century—took it mostly off the radar. During the portfolio era I found the opportunity to do some mixed methods research in naturalistic settings around teaching practices and feedback.

One study I published used student-written reflections collected at three different times across a school year from seventh and eighth grade students getting intense “doses” of portfolio pedagogy and assessment. When they submitted their portfolios each trimester to be assessed, they wrote formal, structured reflective analysis in response to direct questions. Class time was devoted to discussions of these direct questions and to peer-to-peer feedback on their feedback. Some of their best writing showed up in these reflective essays.

Each trimester students were assigned reflective analysis tasks to help them identify aspects of their reading and writing which were improving and to point to evidence in their portfolios. They had to select their most satisfying work and work that wasn’t satisfying; writings were a combination of assigned essays and self-selected writing projects.

They were also asked to identify strong and weak spots in writings along with evidence from their work to help nail down self-definitions so they understood what they needed to focus on. Essentially, they were learning to become critical readers of their own writing. Their ability to pinpoint their improvements and room for growth improved across the three trimesters. Qualitative analysis of their reflective essays introducing their portfolio across the three grading periods showed that they moved from surface worries about what their teacher would like or not like to deeper worries about how well a self-selected text accomplished what they wanted it to do.

Writing teachers using portfolio pedagogy came to understand the crucial function of feedback in the construction of learner intentionality in reading and writing. Establishing a community of writers and readers fosters cross-pollination feeding self-regulation that moves students to say things like “You know what, I want to be a good writer when I grow up even if I’m not that great right now. I’m starting to figure out how to write.” Many of their insights came from their peers

One particular aspect of the reflection repertoire asked them to write about and illustrate two things: 1) What problems did you face this trimester as a writer? and 2) What did you do to resolve them? I used every portfolio completed every semester in three different portfolio classrooms as data (roughly 200 portfolios over three grading periods for a total of 600) and open coded their reflections. During the first trimester, one big problem across the board was “length.” They had trouble writing what they considered lengthy pieces.

Of course, length in itself is not a virtue; lots of times it’s a vice. The interesting part is they knew, many were troubled by the finding. Intuitively, some explicitly, they complained not so much about needing to get more words on the page, but about the difficult problem of getting more good words, powerful words on the page. They were building an understanding that too many empty words are worse than too few meaningful words. Here was an opportunity to teach a collection of emerging writers to “read from the point of view of a writer” and to “write from the point of view of a reader.” Find a piece of writing. What is the writer doing that is satisfying? How can you do those things?

To be sure, since second trimester grades depended in part on documenting and showcasing what they did to solve their challenges, they studied strategies for elaboration and its reverse gear, deletion. It’s tricky to elaborate, knowing you’ll have to cut it back. With demonstration teaching and teacher think-alouds while writing they came understand when to add, cut, rearrange, or rethink words, phrases, even paragraphs.

The second and third trimester reflections revealed a greater variety of questions they surfaced with more specificity. One big problem second trimester was writing leads that would grab a reader. Once again, that problem steered them toward hypothesizing writing. Why did the writer do this instead of this? How did this lead work so well? Why did this one fail? Yes, publish writers fail, too.

*****

The experience that gave me confidence in my emerging thinking about the power of portfolio pedagogy happened ten years before my time teaching middle school. One technique I taught my fourth graders with regard to peer feedback was “point and say why.” It wasn't enough to say to a peer “I really liked this!” What does a writer do with empty praise? Feel good for a second. But what if the feedback is “I really liked it when you described the old car in your driveway. I could almost feel the rust.” Wayne had written about a private place he like to go to to be by himself—an old car. As they got better at pointing and saying why, I saw uses of sensory description spreading like wildfire. Then came the problem of too many adjectives.

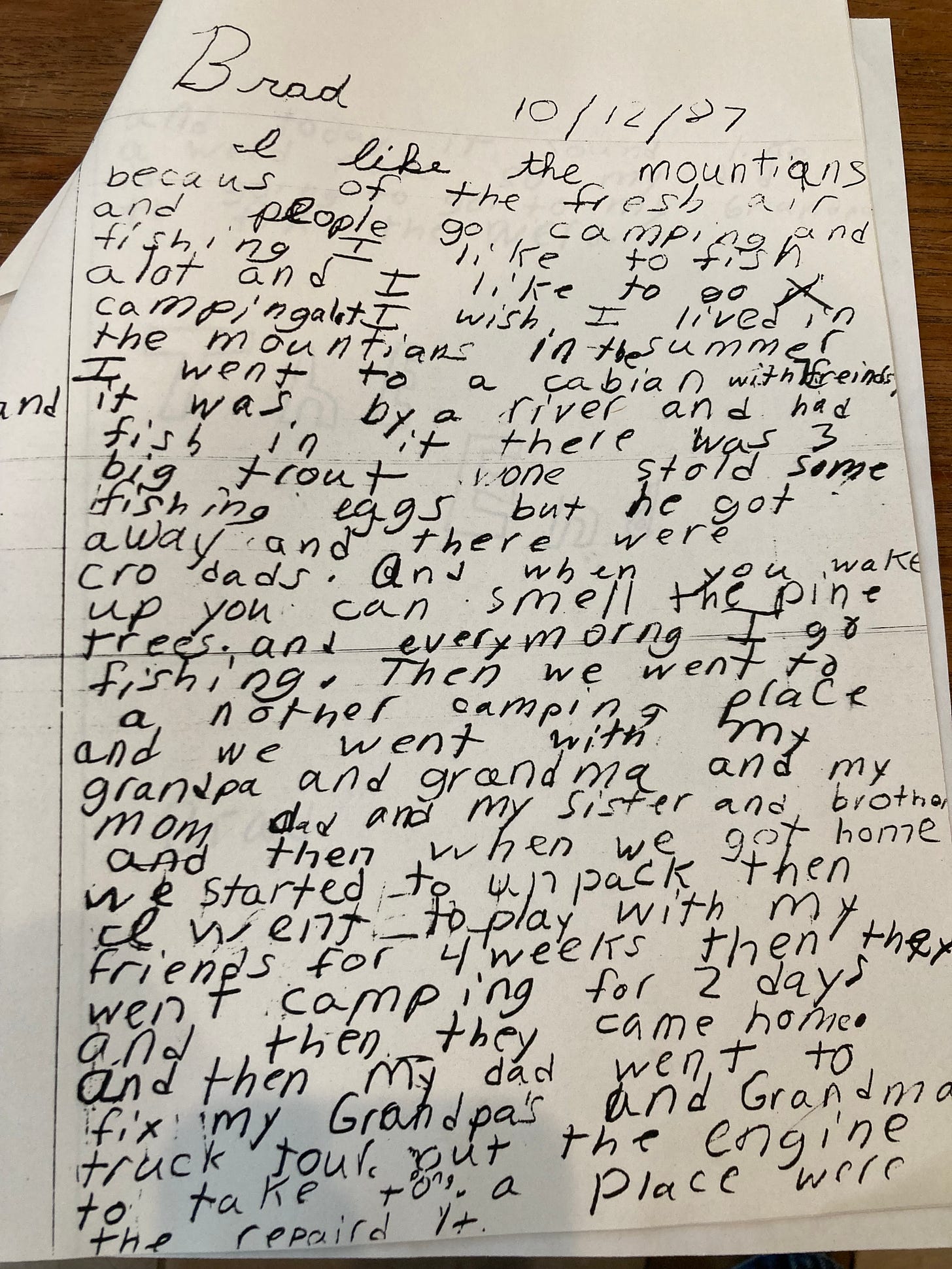

This was a full ten years before my seventh/eighth grade portfolio research. Here is a fourth grade sample, a draft Brad wrote about a place he liked. I can visualize him working on his writings that filled his working drafts folder. He was picky about which pieces he wanted to finish for a grade or for publication in a class collection. Note the date: October. Sensory details became old hat by January. The question became “How do I figure out what detail works and what doesn't without having to be told?”

I also assessed students on feedback take up, how they made decisions about what to revise and what to change. I wanted to make sure they learned to say what they wanted to say and not allow a peer to usurp their writing.

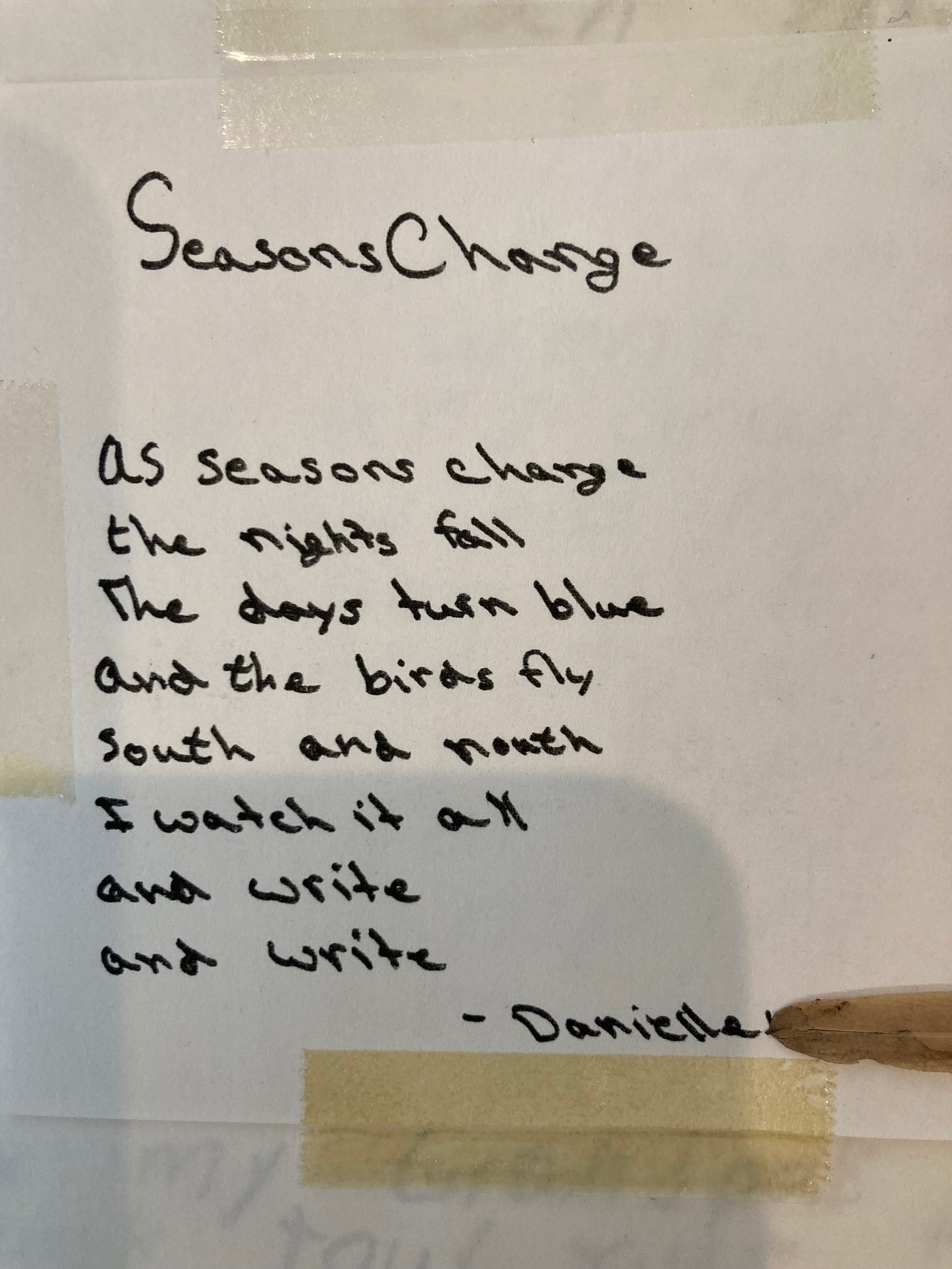

The next piece is among my favorite poems. Danielle was a quiet girl, an old soul who began fourth grade as a struggling reader and reluctant writer. I worried about her at the beginning of the year. She wrote a lot of poems and short stories that year and improved remarkably. When she submitted this poem to me near the end of the year, I could care less about her score on the California Test of Basic Skills.

.

Wonderful to read, Terry, and so much to learn from your methods. Thank you!